Walt Disney Productions (February 15 1950), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (October 2 2012), Blu-ray and DVD discs, 74 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition 1.37:1 original ratio, DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 and Original Theatrical Soundtrack, Rated G, Retail: $39.99

Storyboard:

Poor scullery maid Cinderella’s life is transformed when her nasty step-sisters’ treatment of her brings about the appearance of her Fairy Godmother, who provides the magical means for her to change her destiny and meet her own Prince Charming. But wicked step-mother Lady Tremaine has her eye on her, and plans to switch Cinders’ chances with that of one of her awful daughters…

The Sweatbox Review:

Despite the fact that Cinderella has often been called – as it is in the packaging here – Disney’s ultimate fairytale, it never quite reaches the heights in storytelling or artistic design that Walt’s two other efforts did. Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs was the first, in 1937 of course, and largely set the template not only for Walt’s productions to follow but for the later, more recent Disney fairytale pictures too. Like Snow White and the third of Walt’s original fairytale “trilogy”, Sleeping Beauty in 1959, Cinderella is a product of its time.

Snow White provided just the right elements of fantasy and wonderment for its release in the late 1930s, just before a major war would engulf the world. In a landscape of black and white, albeit sparkly and bright, live-action musicals, Walt’s Technicolor spectacle was also able to support its lush visuals with terrific, taught and suspenseful storytelling and highly-memorable songs, still standards today. Later, Sleeping Beauty was more of an artistic achievement than a huge commercial success, and its expansively enveloping visual style always provided something to keep the attention even if some felt the plot also fell asleep at times (and I’m not one that shares that feeling).

But while Cinderella certainly has its own magic – and some truly wonderful animated touches – the storytelling is a lot less tightly structured. It’s a very slight story, and one that has been adapted before and since Walt’s take on it, sometimes more successfully. Ultimately your enjoyment will be on how much you like singing mice, since there are a lot of them packed in to this version, usually as a way to pad out the running time. As such, Cinderella often stops off on many tangents, either to make time for the mice to retrieve something of importance from pesky housecat Lucifer or to fit in one of the film’s many song ballads.

A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes and So This Is Love may have become standards, but they do their best to sometimes slow the film down much more than a One Song or Someday My Prince Will Come did. Much of this was down to the conditions the Disney Studio found itself in at the end of the 1940s. Although Walt’s color short subjects from 1931 onwards had gained critical applause and an Oscar each year for the Studio, putting it at the forefront of quality animated entertainment and artistic achievement, and the huge feature gamble of Snow White had paid off handsomely in 1937, the following few years were not as fruitful for the company in terms of commercial success.

Artistic progress was certainly being made, over films such as the incredibly lush and detailed Pinocchio, the ambitious Fantasia and naturalistic Bambi, but a second World War had sparked off in Europe, cutting off Hollywood’s – and of course Walt’s – box office returns. Even less encouraging was that Pinocchio had not lived up to the hope of matching or beating Snow White’s phenomenal run and Fantasia, originally a road show presentation, would take years to recoup its investment. Dumbo had proven a bright spot, but the film was a low-budget picture, designed to be turned out quick and make a profit.

That it also turned out to be one of Walt’s best is beside the point, and it did make money in England, but the British government decreed that, to assist in their war effort’s economic recovery, all monies generated by foreign product had to be reinvested in Britain (thus prompting Walt to open a satellite production office in England, where Treasure Island and a trio of Richard Todd period adventures would be made, among others, throughout the 1950s). The war was, in a way, beneficial to the Studio too: with a lack of income from its animated product, Walt somewhat welcomed the military onto his lot, which became a hotbed for animated propaganda and training films.

Walt was able to keep the entertainment side of the company afloat – just – by cutting back on the full-length films and turning to producing what became known as the Package Features: essentially compilations of special short subjects that might have otherwise made the Silly Symphonies series (indeed, several segments from these films were late made available as individual shorts by themselves). Combining entertainment with his patriot duties (and shipping Walt away from the Studio while his brother Roy dealt with the infamously ugly cartoonists’ strike of ’42), a South American themed picture was deemed successful enough to warrant a sequel and further spin-offs.

Other films in this line were more music-orientated, and sometimes unfairly criticized as being a “poor man’s Fantasia” when all they were striving to do was to entertain and perk up the nation after the horrors of the long war. A gradual move into live-action meant Disney could increase its filmed output, the result being the charming and undeservedly still un-re-released Song Of The South among others. The Package Features slowly returned towards full-length aspects, too: Fun And Fancy Free was primarily made up of two half-feature length stories mixed in with some interstitial material, while The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr Toad was a straight feature simply told in two halves.

Walt knew he couldn’t keep coasting along on compilation films alone, and the gradual move back to features was intentional. The Studio had been coming up with ideas for a new full-length film since the early 1940s but nothing seemed to click, either because of timing or lack of funds. Snow White had been such a success that Walt reasoned the Studio should make a new fairytale picture: it was time to turn Cinderella, a story that had been on and off in development since the 1930s, into the next Snow White. Perhaps the high intention – maybe even call it desperation – to create a sure-fire hit film is at the heart of my slight dissatisfaction with the result.

Oh, it’s a great Disney fairytale to be sure, but the cookie-cutter aspects – the storybook opening, opening song introducing our heroine, the wicked stepmother, comedy sidekicks, sloppy love ballad, happy ending, etc – just feel a little too calculated to me. It’s true that there are several new elements that give things just enough difference so as to not make the picture a carbon copy: Prince Charming himself isn’t really given much more to do (it would take Sleeping Beauty to give us a Prince who does more than just turn up), but there’s a family dynamic in the Prince’s father the King being a classic Disney royal stereotype, and his pal the Duke being just as befuddled, bringing about some good natured, gentle humor.

Some of this is to pad out the length, too: at its heart the Cinderella story just isn’t packed with enough incident, and almost every version I’ve seen tends to give over a lot of screen or stage time to other elements (indeed, traditional English pantomime productions include an entire extra character, Cinders’ friend Buttons, who gets his own contributions to the story). Walt’s preference was to go for mice (after all, a mouse had been a pretty good-luck charm for him so far in his career!), and just as the Dwarfs assumed various personalities in Snow White so do the little mice in Cinderella: Jacques is the clear Doc-styled leader, while newcomer to the group Gus is more Dopey-like in nature.

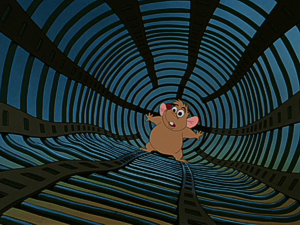

The two make for a fun pairing, while the rest of ’em contribute in other ways. Uniquely, the mice can “speak” (or should that be squeak!?) to Cinderella while the rest of the animals are much more authentic in their behavior (even when magic renders them human). It’s also a good job that Jacques and Gus are good entertainment, since they’re asked to carry a good deal of the picture: sometimes, for instance when they head off to grab a necklace for Cinderella to wear and are confronted by Lucifer, one could be forgiven for thinking they’re watching a typical animated short about two mice and a cat. This does prove to provide a good deal of comedy, however, but doesn’t always help the somewhat episodic nature (perhaps a remnant of the Package Features’ thinking).

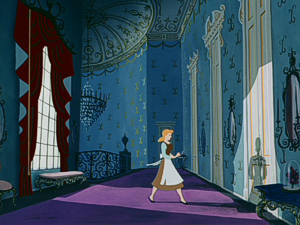

So where Cinderella really scores is in a number of specific elements and sequences. The animation, as you would expect, is pure quality…the result of a minimalistic live-action shoot that provided the artists with all the reference (and note: not rotoscope) they needed to make Cinders, the Prince and the wicked Lady Tremaine believable humans in an otherwise fully animated landscape. Falling somewhere in between is the Fairy Godmother: more caricatured perhaps but still very much a “real” person despite her magical background, and bringing with her the film’s signature Bibbidy-Bobbidy-Boo moment, where the animators really get to play with their form and some wonderful effects animation predate the kind of “morphing” that’s two-a-penny in these CG days.

Other sequences that deservedly play a part in establishing the Disney style also include the storybook opening, whose illustrated pages slowly mesh into the animation itself. Nowadays, when all our lead characters seem to have had a troubling past or dark and tortuous backstory to surmount, it wouldn’t surprise me to find that these opening few minutes would be stretched to an entire 20-minute opening act but here it’s all very succinct and to the point, quietly setting up Tremaine as cool and calculating before the story really gets going. Tremaine is in many ways the very grounding force of the film: despite the magic and fantasy it’s her very real nature that plays in perfect counterbalance (another note about the film’s look can be made about Mary Blair’s concept art, which uniquely finds aspects of itself in the eventual layouts and backgrounds).

Likewise the film’s ending, where the Duke searches for the mysterious girl the Prince ultimately meets and falls in love with at his royal ball, is bathed in suspense, with the little mice racing against time and the efforts of Lucifer to thwart their release of a captive Cinderella high in a turret tower. It’s moments like these that do raise Cinderella to the ranks of classic Disney and, while the film may deviate from its central core a little more than some others in the canon, it also provides some core Disney fairytale conventions. As such, perhaps Cinderella is the ultimate fairytale: can there be one symbol other than the famous glass slipper that epitomizes the entire sub-genre any better?

It’s perhaps this association with footwear – high heels traditionally being a female choice – that has seen the film designated “little girl” status primarily in terms of audience recognition. Certainly the Studio has subsequently aimed it at this demographic for the most part: in 1950 it was sold as the greatest love story ever told, while even recent reissues promoted the romance over anything else; even this new Blu-ray release comes in one package as part of a “jewellery case” set – not clearly tied to any aspect in the film other than its reputation as one of the central franchises in the Disney Princess line.

But although the 1950s’ dating of the film somewhat now plays into those notions, there is more to Cinderella than this: even if one feels Walt was playing safe by going for the same kinds of choices that had proved a success for Snow White, they’re still by and large good choices! Cinderella may not be the most original take on a fairytale that the Studio ever produced, but in many ways it develops the template set up by Snow White and allows for the contemporary touches that would come in the Studio’s renaissance era of The Little Mermaid, Beauty And The Beast and Aladdin (itself not really a fairytale per se, but containing enough of the elements at least).

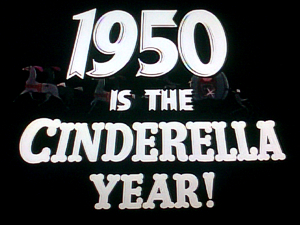

Cinderella proved to turn out just what Walt was hoping for, too: a terrific success both on the screen and in merchandising, a perennial title that kept on bringing healthy returns and going in no small part towards assisting Walt’s television and theme park expansion. As the Studio announced in its marketing, 1950 proved to be “our Cinderella year” and, some 60-plus years later, it’s still proving to be, this new restoration creating some bibbidy-bobbidy magic of its own and giving us a chance of seeing Cinderella every bit as clear and sparkly as that glass slipper.

Is This Thing Loaded?

For those that remember such things, Disney’s Platinum DVD Edition of Cinderella was a very disappointing affair. I think the line around that time had, or was about to, switched to two titles being released per year instead of the usual single fall release, and there are no doubts that the quality of some of the later titles suffered in terms of truly great supplements included in those packages. Despite a previously wonderful and elaborately lavish LaserDisc box set being released with plentiful supplements in the 1990s, almost none of them were drawn upon to fill the original DVD edition, which resulted in a lot of fluff including some kind of ESPN-related clip about sports stars and their own happy endings.

Yeah, I know…ESPN on a Disney edition of Cinderella!? Thankfully, that kind of thing has been dropped here, in favor of the best of the previous DVD supplements as well as some of the audio-only goodies from the LaserDisc set. Once again it’s a lighter than usual collection, although unfortunately I can’t make my customary comparisons with the older versions since they’re currently boxed up awaiting a move of house! So we’ll simply have to see what’s on offer here…but in short there’s a lot I remember, and a lot I don’t, so the mix seems to be pretty reasonable. I was wondering how Disney’s animated short Tangled Ever After (6:29, in HD and 7.1) was ever going to make it to disc: this “mini-coda” to the Studio’s Rapunzel feature premiered with the 3D theatrical reissue of Beauty And The Beast – a title which itself was already available on Blu-ray.

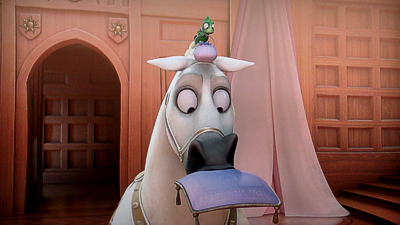

Luckily for us, the Studio hasn’t announced that we have to buy Tangled all over again and has included it – rather appropriately it must be said – right here, with much fanfare on a front cover sticker announcement. Okay, so this has scant all to do with Cinderella either, but on the flipside it makes for a fun comparison in terms of their approaches on the same material. Both naturally feature fairytale conventions, and in the sidekicks Maximus and Pascal’s adventures in trying to locate Rapunzel and Flynn’s wedding rings while the ceremony has already begun, there’s more than a whiff of Jacques and Gus’ battling the clock to get Cinderella the key to open the door of the room she is being held in.

Of course the animation style is as different as could be: the smooth, delicately drawn lines of 1949 replaced with whizz-bang sleek and shiny CG – but it’s really, really nice sleek and shiny CG! Going completely over the top in terms of the devastation to the kingdom’s surroundings, Tangled Ever After is simply a lot of very well crafted fun. Although he’s not credited as being involved, it’s clear Glen Keane’s traditional animation touches have been felt by the current Disney artists: the animation here is sublime and timed to perfection. Tangled’s original directors return for what could basically have been a final rousing chase sequence for the movie itself: I laughed out loud two or three times and I’m sure you’ll enjoy this too!

Cinderella itself plays with a couple of “bonuses” of its own, the first being the return of the DisneyView option that paints-in background styled panels to fill the left and right areas of the 16:9 screen that the 1.37:1 Academy ratio animation doesn’t fill. I’ve stated my dislike of this option before, since I think the effect can actually detract from, and overwhelm, the actual movie we’re supposed to be enjoying. Here Christy Maltese’s images are nice enough but equally distracting, often being too colorful and – my old beef – not moving when the camera does, giving an unnatural feel. Grouped somewhat by location, these side panel scenes change depending where the action is being set at the time: there’s obviously a lot of work that goes into these, but ultimately they take away rather than adding anything.

The second option is also useless: I’ve also stated my dislike of Disney’s Second Screen additions in the past, in that they seem to offer the kind of supplemental material that should be right on the disc, but this one drops even that idea and simply goes into offering a Bibbidy-Bobbidy-You Storybook application that “inserts” you into the story – or rather an animated storybook version of the story that seems to play as the movie runs. Without any actual behind-the-scenes incentive or the real need to see myself interacting with Cinderella’s mice friends, I took a pass, although if you can be bothered to download the app and go through the lousy syncing issues that continue to plague Second Screen options then I guess very young children might get five minutes of fun from it.

The movie can also be played with a brief Introduction by Diane Disney-Miller (1:16). Once more welcoming us to the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco, Diane elaborates a little on how important Cinderella was for the Disney Studio at the time, allowing as it did Walt’s move into television and theme parks. Heading into the Backstage Disney section of the disc, the slightly tenuously linked The Real Fairy Godmother (11:50) profiles Mary Alice O’Connor, wife of the legendary Disney background artist Ken O’Connor, who based his design for Cinderella’s magical lady on his own wife. As is befitting for such a story, it turns out she carried out many a good deed herself during her life in Burbank, and with some extra Studio tid-bits this escapes from being a superfluous addition.

More fluffy, but actually interesting for fans of Disney’s parks, is Once Upon A Time’s Ginnifer Goodwin-hosted look at Walt Disney World’s magical revamp, Behind The Magic: A New Disney Princess Fantasyland (8:17). Expanding the original Fantasyland to more than twice its size, new additions will include attractions based on Beauty And The Beast, The Little Mermaid and Snow White. This clip, ultimately promotional in nature and lacking any Cinderella connection other than a fairytale link, still excites however. As much the California’s Cars Land failed in elicit much response from me when that was trailed on Cars 2, I was super-excited to see what they have in store at New Fantasyland, and hope to make the trip to Orlando to experience it for myself.

I was expecting the Christian Louboutin-endorsed The Magic Of The Glass Slipper: A Cinderella Story (10:03) to be another nauseating publicity effort to get us excited about the glass slipper shoes the famed footwear designer was engaged to create as part of the publicity surrounding Cinderella’s Diamond Edition release, but what we get is something quite different. Far from being a boring, almost non-related documentary piece on how inspiring he found Walt’s original classic, blah, blah, blah, what is actually served up is nothing short of a stand-alone short film, in which Louboutin is apparently washed-up. Uniquely featuring new animation, his French mice friends help him as they helped Cinderella, and inspiration is achieved! Louboutin isn’t really required to “act” as such, and the second half could be cut down to an arty commercial for his trademark red-soled shoes, but it’s an elaborate inclusion and the Louboutin sketch come to life (through Eric and Susan Goldberg’s Cartoons In The Basement) is priceless.

A hitherto unseen Alternate Opening (1:13) is really nothing of the sort, and even the context-placing text skirts around the issue of it being a legitimate “opening”. What it most certainly is resembles more of an alternate or earlier take on A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes, and the dialogue is clearly intended to be sung in some way. Very brief, it is of course nice to see, but a lot of the ideas, and even one lyric, ended up in the resulting picture without much other change. That’s it for the new HD extras – and at this point I’ll also make a note about the annoying menu design, which is too loud audibly and with light, hard to make out text – leaving us to go to the series of Classic DVD Bonus Features carried over from before.

Heading this list is a further series of Deleted Scenes, which run almost ten minutes including a vintage Introduction from Don Hahn, who places the scenes in context. An alternate Cinderella Work Song, sans mice, has been (then) newly recorded to accompany the artwork that sees Cinders imagining that she has multiplied herself in order to finish off her chores, while Dancing On A Cloud is a lovely romantic moment played from the original song demo that those with the LaserDisc sets will also be familiar with. There’s another vintage demo pulled from the archive to present the Cinderella Title Song (2:15) in its original form, although no context is provided.

LaserDisc fans will remember the hours of supplemental audio provided on alternate tracks of the discs’ extras disc, some of which has been carried over here in the form of an Unused Songs section that presents more demo recordings. Again, there’s no context, but fans should be able to piece together the moments that these songs might have been written for: among them are Sing A Little, Dream A Little, the happy and zippy I’m In The Middle Of A Muddle, The Mouse Song, The Dress My Mother Wore a reprise for Dancing On A Cloud, I Lost My Heart At The Ball and The Face That I See In The Night. The recordings vary in quality (both in terms of being dated in the 1940s and in terms of audio levels from what must be archival 78rpm discs), but some of them are great: Middle Of A Muddle and Dress My Mother Wore have both been favorites of mine since the LaserDisc set, and there’s almost 20 minutes to unearth here.

Further archive audio can be heard in a selection of three Radio Programs, totaling over twelve minutes in all. They make for very fun listening, from the announcement of Ilene Woods as Cinderella herself, in a 2½ minute Village Store Excerpt from 1948 in which she sings When You Wish Upon A Star, through a 5½ minute Gulf Oil Presents Excerpt (circa 1950) that starts to promote the upcoming movie itself during production. Best of all, Scouting The Stars, (4 ½ mins, also from 1950, finds the Studio in full promotional flow, using the widest reaching medium at the time to sell Ilene’s Cinderella-styled discovery in a classic pre-written interview in which everyone says what they’re meant to (“You’re luckier than your listeners, Bill: you’re getting to see Ilene, they’ll only hear her!”), but it’s still great to hear directly from those involved in Cinderella’s production.

Like many of the LaserDisc sets of the 1990s, Cinderella contained a fantastic documentary on its making from the Kurtti/Pellerin team that fans with that set will want to keep just for that account of the film’s production. For the more recent Platinum Editions, Disney replaced those documentaries with newly produced behind the scenes stories relayed by the current generation of Disney artists and animation historians, themselves fans of the films that inspired them. From Rags To Riches: The Making Of Cinderella (38:27) features again here, and although I don’t think it’s as in-depth as the LD piece it still features a pretty good coverage of events.

There’s a lot of praise for the film and its various ingredients early on, but once the thing gets moving it begins to focus on specific elements, from a quick overview of Walt’s so-called Nine Old Men and the film’s live-action reference shoot (with the stress on the animation not being rotoscoped), through the casting of Cinderella’s voices (did you know “Cruella de Vil” provided the opening narration?), and its wonderfully timeless songs and focus on commercially popular songwriters, to a glimpse at the premiere and its ongoing reputation as a classic.

The documentary was originally split up into featurette-style segments on the DVD, as far as I remember, and so playing it as one piece can feel a little less coherent as a production document than it does a series of focus points, although this time we do hear from Marc Davis, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and Ward Kimball, which is great. But otherwise the general lack of archive animator interviews in favor of new faces (even if they include Johns Culhane and Canemaker, Andreas Deja and Glen Keane) sometimes gives it a slightly “second hand” flavor. That said, there’s still much to enjoy here, from analytical praise to production anecdotes, and even long-time aficionados should find their interest is captured by the various aspects covered.

The Cinderella That Almost Was (14:08) finds Don Hahn looking through the Disney Archives to present a background to a much earlier version of the film, touching on Walt’s 1922 Laugh-O-Gram, providing decent context for when that short turns up in full later in the supplements, and a proposed but never made 1933 Silly Symphony idea back from before Walt started to prepare to adapt Snow White. But the emphasis here is on a late 1930s take as a full feature, which might have presumably followed Snow White’s success, and the various development it went through in the 1940s. This isn’t exactly an alternate version of what might have been but more an amalgamation of ideas and concepts from over that developmental period, the most notable being a different take on Cinderella’s animal friends, which provides some fun stuff, and the deletion of a music instructor character previously only seen in the LD supplements.

Probably the best and most straight-out entertaining of all the extras here is From Walt’s Table: A Tribute To Disney’s Nine Old Men, another featurette tenuously linked to the movie itself, but substantial at 22 minutes and hugely enjoyable. Seven has always been a lucky number when it comes to Disney Animation, and here that number of current artists are gathered by critic Joel Siegel at Walt’s famous haunt, the Tam O’Shanter Inn in Burbank, where he and his closest animators would gather to go over ideas. Returning to Walt’s table with the likes of Hahn, Glen Keane, Andreas Deja, Brad Bird, John Musker, Ron Clements and Mark Henn, there’s the danger that their anecdotes could again come over as second hand, but nothing could be further from the truth, since these are stories about this current band of artists and their interaction with the original Nine Old Men when they started at the Disney Studio all those years ago. Enthralling, and sometimes very funny too!

If the Nine Old Men was Disney’s boy club then the only woman who might have ever gained access would have been the conceptual artist Mary Blair, who provided exceptionally stylized artwork on and off for the Studio from the 1940s. Originally coinciding with Canemaker’s similarly titled book on her life, The Art Of Mary Blair is explored in a dedicated 15 minute featurette, detailing her work on Walt’s pictures of the 1940s and 50s especially. Hers was a style all of its own, and one that Walt often struggled with in adapting for animation, but where she really scored was in setting a mood through color. This is a great overview of her life during and after her Studio work…a more than fitting celebration of this only rather recently recognized artist whose work continues to inspire today.

It would have been great to have had a picture-in-picture track throughout the movie (see the What’s Missing? comments below), but as something of a token gesture in this regard, a Storyboard To Film Comparison (6:49) shows us the kind of thing that might have been. Offering up the early A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes sequence, a split between the final film and the pencil sketch and live-action shoot images reveals how the scene was planned to come together. Mentioned in the supplements above, Walt’s 1922 Cinderella Laugh-O-Gram (7:24) is next, presented from an archival print with the same silent movie piano track as debuted with the LaserDisc edition. A then-contemporary version of the story, the 1922 Cinderella doesn’t bother to find time for story-padding mice and the like (although a cat and dog get some of the best gags), and even relegates Cinders to almost secondary status in favor of a dashing hunter, the Prince.

Cinderella herself is given a typical 20s flapper type makeover by her Fairy Godmother and quickly catches the Prince’s eye at his ball. Since its first official release in the LaserDisc set, Cinderella has popped up in other compilations on DVD, so by now most will have come across it somewhere or other and know what to expect. The animation isn’t as natural as the later 1950 version, obviously, but there’s a real charm here considering these were Walt’s formative filmmaking years, and there are some unexpected touches here and there (the “Multiplane” street at night) and the trademark attention to story: there’s no flab and the thing just keeps moving, buoyed by a fun approach as many of the Laugh-O-Grams had.

Television was always a great way for Walt to promote his library of films, and Cinderella was teased by having the live-action shoot’s original Cinderella model make an appearance on one of his shows. An Excerpt From The Mickey Mouse Club With Helene Stanley is a near-four minute clip taken from a 1956 Guest Star Day episode, in which Stanley turns up to explain what she did for the movie. There’s some fun to be had when the Mouseketeers join her in a version of the Cinderella Work Song, and its clear she understands how to act for the animators: something she would repeat for future Disney films as Sleeping Beauty and One Hundred And One Dalmatians. Finally, a nine minute series of Theatrical Trailers round up the 1950 Cinderella’s supplements, showcasing the original 1950 release and reissues for 1965, 1973, 1918 and 1987.

On the included DVD, Cinderella gets the same Enhanced Disney Home Theater mix as it did on the Platinum DVD, as well as the Diane Disney Miller Introduction, Tangled Ever After short and Behind The Magic: A New Disney Princess Fantasyland. Sneak Peek previews across both discs include Peter Pan’s Diamond Edition debut, the Studio’s upcoming feature Wreck-It Ralph, Tinker Bell’s Secret Of The Wings, Disney Junior’s CG-animated/2D-shaded Sofia The First animated series, Brave, the Cinderella II & III 2-Movie Collection, Finding Nemo and seemingly now obligatory Planes teaser, along with an anti-smoking spot and the usual Disney promos for the parks and the like.

WHAT’S MISSING?

As mentioned above, I can’t make the usual comparisons due to my previous editions of Cinderella – the LaserDisc box and the Platinum DVD – being locked away in a tower of their own, but I do recall the LD contained a good portion of Art Galleries, from Character Designs through to Backgrounds, and a lot more audio-only programming; there was, of course, an alternate and arguably better documentary on that set too. It’s been a while since I went through the DVD, but even here I remember the Galleries being a big part of that presentation, along with some set-top games that are less lamented in their loss.

It’s a real shame that the Galleries seem to be something dropped from the current crop of Disney editions, especially when they might have been used as picture-in-picture content over the main feature. How cool might it have been to see original character designs fade up and down as a new character was introduced, or some of the background elements as the film moved around different locations? The lack of any addition to the film, by way of commentary or picture-in-picture track, is severely disappointing, and even the Second Screen option offers nothing in this regard.

However, the new extras – especially the Tangled short – are welcome and go some way to making up the selection: it’s not the best Diamond package, but this edition of Cinderella does beat the Platinum set in most regards, the total and unappreciated lack of Galleries notwithstanding.

Case Study:

Offered in a variety of packages (including a “jewellery case” box set also containing the soon to be individually released video sequels), Cinderella is best represented by the Blu-ray packaged editions, of which there are two: a standard Diamond Edition Blu-ray and DVD combo pack (reviewed here) and a second, golden-tinged pack that also fits in a Digital Copy disc. Quite why Disney didn’t just offer the all-in pack as standard is odd…I can’t think of many people that would pay $5 more for a digital file, and arguably the “standard” BD artwork matches the other Disney Diamonds better than the gold-colored digital copy edition.

Everything else about this regular edition is as expected: an embossed slipcase offers the usual Disney blu-themed border coloring on the front and plethora of pamphlets and booklets inside. Tangled Ever After is teased on a sticker, while the back of the sleeve fails to include all the bonus features so the selection looks unfairly slim (there’s much more to be found on the disc). The Blu-ray Guide inside doesn’t add anything to this, surprisingly, and is more content to promote the Second Screen app and BD debuts for Peter Pan and The Little Mermaid next year. The Disney Movie Reward code and a Cinderella-themed promo booklet complete the package.

Ink And Paint:

Presented intact with its original RKO distributor’s card, Cinderella has undergone another of Disney’s wonderful digital restorations that visually offers the film literally in better condition than audiences saw it back in 1950. Yes, it could be argued that original defects such as cel scuffs and inherent dirt in the frame captured on the animation camera stand itself should perhaps remain as historical artefacts (actually, some are still faintly visible), but the aim of these editions is to present the films as if they had been assembled in this digital age.

Very eagle-eyed among you may notice that the paint in the original cels can still be seen, although not all the time, and there’s a slight ringing around the characters on occasion, where the restorers have circled around the characters so as to not remove any of the animators’ original lines. But this is as good as vintage animation can look and as with Snow White and Pinocchio before it, this new Cinderella sparkles like its famous glass slipper, offering new appreciation of the animation and background artistry.

Scratch Tracks:

Disney’s 7.1 DTS track – pulled apart from the original mono stems – isn’t as successful in being as up to date as the image, but this is still the best Cinderella has ever sounded. It’s still a front-centric mix, the surrounds only really ever coming into action in the more rousing music and some spot effects, but the clarity is the real note here. For purists, the restored mono track is present, with clicks, pops and hiss removed, and if anything it has a little more dynamics even if not the speaker separation.

Final Cut:

Cinderella’s reputation clearly precedes it, and the film has rightly become a Disney classic. It has all the elements perfectly in place, although for me it’s all a little too perfect. The treacherous Lady Tremaine is the standout character here: her face at the film’s ending, when she knows her all her scheming has come to nothing, is priceless, and the film does have some softly emotional moments, especially in the vocal performances, that I found I appreciated even more now as an adult.

It’s always been a favorite of little girls everywhere, perhaps because they all dream of having their Cinderella moment themselves, but there’s action, comedy and excitement in here too. On the one hand it may be too closely modeled on Snow White, but on the other it reaffirms the principles of what we know as the Disney fairytale, and certainly without it we may never have had any of what was to follow. And that’s a happy ending we can all get behind!

| ||

|