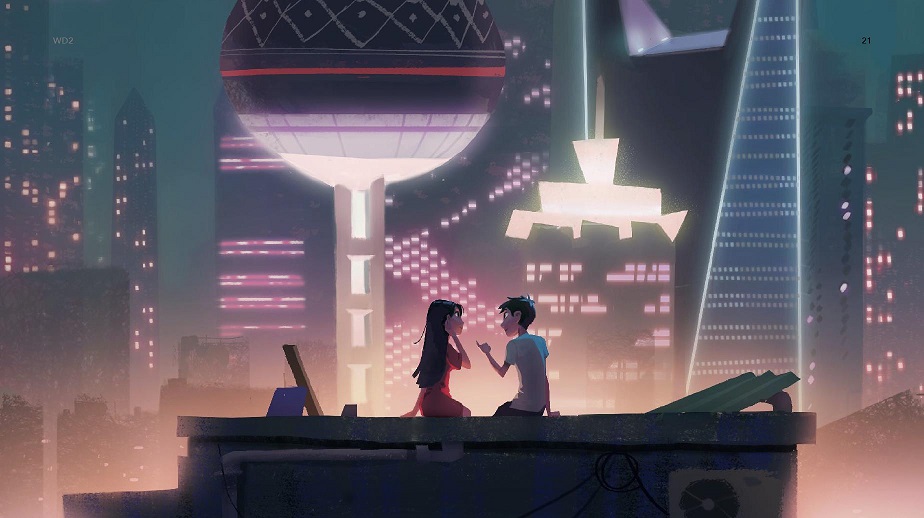

In Sony Pictures Animation’s Wish Dragon, available June 11 on Netflix, Din, a working-class college student with big dreams but small means, and Long, a cynical but all-powerful dragon capable of granting wishes, set off on a hilarious adventure through modern day Shanghai in pursuit of Din’s long-lost childhood friend, Lina. Their journey forces them to answer some of life’s biggest questions – because when you can wish for anything, you have to decide what really matters.

In Sony Pictures Animation’s Wish Dragon, available June 11 on Netflix, Din, a working-class college student with big dreams but small means, and Long, a cynical but all-powerful dragon capable of granting wishes, set off on a hilarious adventure through modern day Shanghai in pursuit of Din’s long-lost childhood friend, Lina. Their journey forces them to answer some of life’s biggest questions – because when you can wish for anything, you have to decide what really matters.

If you see some analogy with the story of Aladdin, you got it right, as it was originally a Chinese folktale; and director Chris Appelhans thought it would be interesting to set it in the country that created it, but with a present-day twist.

To accompany musically that voyage between tradition and modernity at the heart of China, Chris Appelhans appealed to composer Philip Klein. Philip’s music has been heard in film and television projects for Sony, Disney, Pixar, Lionsgate, ABC and CBS. Recent projects include the Roadside Attractions drama The Last Full Measure, and Neon’s Pig. He also penned 18 new orchestral arrangements for Aerosmith’s Las Vegas residency, Deuces Are Wild. As an additional writer, Philip has collaborated with some of the finest composers working in film and TV, including Harry Gregson-Williams, Carter Burwell, Alex Heffes and Fil Eisler. He is also in demand as an orchestrator, having had the honor of working with James Newton Howard, Alexandre Desplat, Ludwig Göransson, Hildur Guðnadóttir, Steve Jablonsky, David Buckley, Stewart Copeland and several other amazing artists. Recent orchestration credits include the Oscar winning Joker, Oscar nominated News Of The World and Disney’s Raya And The Last Dragon and The Mandalorian.

Here’s our conversation.

Animated Views: How did you come to work on Wish Dragon?

Philip Klein: I am good friends with one of the Producers. His name’s Aron Warner. He’s done all of the Shrek films. He’s kind of a genius when it comes to animation. He had been working for a while with Director Chris Appelhans, and he thought that I would be a good fit with Chris. I submitted some demos and got some meetings with both of them. Chris and I just got along really well from the beginning, so it felt like a natural fit. It was a joy to work on a film like that. When you get such a nice film, it makes your job easier as a composer.

AV: What’s the spirit of the music of Wish Dragon?

PK: None on the film really wanted us to go down a completely Eastern path, with a completely Chinese score. And obviously, I’m a Western composer. So, what we set out to do was create something that was very layered; use influences from that world, but do it in a more unique way rather than just putting soloists on top of the Western orchestra. So, we got very deep into Chinese folksongs and traditional instruments. It was fun working on those. It made us feel certain emotions. And then I either played them on my own, or I hired soloists from all over the world and started to get audio back. Then, we just kind of manipulated and used it in interesting ways as textural things. For Din, the main character, who is very bouncy and happy, a lot of his music is based on plucked instruments that we used as rhythmic texture things, whereas for the more romantic elements or kind of grand and broad elements, we would take winds or even strings. So, I think it’s a layered score that lives in this Western and Eastern environment.

AV: Can you tell me more specifically about your Eastern inspirations?

PK: You know, when they’re brought on to an Asian score, some Western composers choose to use the pentatonic scale. Even if you’re not a musician, you can recognize the sound of those five notes as being Eastern, Asian sounding. But Chris and I never really thought that was appropriate. So many of the Chinese folksongs are kind of based in that world but we more used them for the harmonic elements and kind of the performance of them, how the instruments were being manipulated to play that way. And then, we said, “Okay, these two instruments work really well together and it makes us feel like we’re with family. These are just two family members in the corner of the room playing together.” For instance, we would have the Chinese moon guitar, which is call the ruan, and then we would have also the guqin playing with that, because those two playing together felt like a very natural duet and are often used in folk music. So, we were taking influences from the orchestration of things and also the mood of that stuff. We never directly lifted thematic material from that. It was more just to inform me of the kind of feelings that you could get from these instruments and how I could use that in the score.

AV: The choir seems also very important in that regard.

PK: Yes. I’m a big choral fan. There’s a lot of fun sequences in the movie, like when Din makes his first wish and he doesn’t even know he’s making his first wish, and suddenly he has this ability – without giving the movie away – to do something very traditional. So, I used a lot of like Asian shouting which the choir had a great time doing. So, the choral shouting and stuff like that seemed pretty natural in that world. And it adds a bit of lightness and kind of fun because of what’s happening on screen, and then there’s also the more traditional choral stuff like near the end of the film as we get into the more grand emotional statements of what’s happening on screen.

A lot of that kind of material in Wish Dragon is also based on Chinese operatic percussion. We did quite a bit of pre-recording with traditional Chinese percussive instruments like gongs and large drums that are bigger than anything we can see here in the Western world. There’s a theatricality to that playing that worked really well when we put it up against the action sequences in the film, and it gave this momentum that just the orchestra couldn’t do on their own.

AV: The choice of the “pipa god” as one of the main characters shows the importance of music in the movie.

PK: He was in the script from the beginning. They didn’t necessarily know the piece of music that he was going to play, and he ends up playing one of the most famous pipa pieces in Chinese repertoire. We found a brilliant pipa player whom we licensed the performance from and then they animated it. I had to take videos of pipa players playing because the animators needed to know how it is actually played in order to animate the first sequence of the movie. Pipa is not played like a traditional guitar; it’s held differently. And then the pipa became a pretty large character in the film. I was using it throughout the score as another element of plucking, rhythm and energy.

AV: The film is set in Shanghai, a city that presents an interesting blending of tradition and modernity. How did you echo that aspect in your score?

PK: You could balance the old and the new in this movie in a lot of ways. Din and his mother still live in an old “shikumen,” which is very old Shanghai traditional housings; and then on the other side, there’s this massive urban growth of the city. So, there’s that sequence at the beginning of the film when we kind of timelapse over Shanghai being built up, and you get a more modern synth-heavy piece of music playing over that, and it kind of thrusts you into this new world. What Chris and I always tried to do on any part of the story that deals with Din and Li Na, which is kind of a friendship-romance-present-day-story, we balanced that kind of thematic identity and that kind of sonic world with more synthetic textures. They have a little thematic motive between those two that’s based on just a little fluttering, pulsing little synth, and that pulls you more into the modern world; whereas when it’s more about Long’s life, the Wish Dragon, we let the orchestra come up a little higher in the mix and it gets a little more grand and traditional. We allowed the Chinese instruments to go a little more forward, too, to sound a little more “old world”, in a way.

The same with the bad guys, the bad goons as they are referred to. They kind of chase Din throughout the movie, and they’re very modern, they look like they’re on the cutting edge kind of guys, and a lot of those textures are very synth-heavy, with heavy basses. Again, using Chinese elements, but processing them to make them sound a little more modern than traditional. So, I think there’s always this kind of dichotomy between the modern story, which is the bad guys chasing the girl and the boy that are somehow falling in love, but it’s more of a friendship thing; and then the grand, traditional story of this Chinese fable that we’re being told, with the three wishes and stuff. It was great, because it allowed the score to live in two worlds without ever feeling that one was too much. You never get sick of hearing all the new because you’re balancing it with the old and vice-versa!

AV: One of the orchestrators of the film, Weijun Chen, is also Chinese.

PK: Weijun has been working with me for a few years now. He’s a brilliant composer in his own right. He definitely sent me to school at the beginning of the process. He wrote a bunch of cheat sheets for me about the instruments. In the beginning, the score was like an open book. Chris and I knew that we could use all kind of traditional instruments, shengs (mouth-blown organ), xiaos (flutes), pipas and guzhengs, and so many more, but I said we had to set certain limits because otherwise it starts to get really unfocused. That’s why I turned to Weijun to help me and give me the basics about range, the traditional use of each instrument, how it’s notated, all this kind of stuff. And he really helped me quite a bit through those initial ideas of, like, “this I think can make sense here” or “this maybe isn’t the right thing for this movie” or “if we put these two together, I think it would be a really nice sound.” He didn’t do any specific writing, but he definitely introduced me to a completely different culture I had not had the fortune of working with in that capacity yet.

AV: The film is also very authentic in its emotions. How did you approach that emotional aspect of it?

PK: Chris was so concerned about always having an emotional core to the story. I think it’s very evident, because you do at the end of the day care so much. I mean, they’re all having these relationships that you’re caring about: Din and his mother, Li Na and her father, Din and Long. There’s a multi-layer of relationships that’s going on and those were always the kind of jumping-off point when Chris and I were starting talking and working together to find thematic ideas for those moments. Because, if we could find the apex point of these relationships, and work to that point, we could de-construct the score and kind of put it together and know that we’re aiming for this moment. For instance, at the end of the movie, Din and his mother share a very, very sweet moment and there’s some beautiful dialogue between them. I always knew that it was going to be the moment when Din’s theme has its most direct and honest statement. The same for Din and Li Na and Din and Long. All the characters have that kind of arc in their relationships. And it is hard as a composer when you get to the end of the movie because there’s these emotional moments happening all the time, and it’s like, “Okay, how do I not just hit the audience over the head with this emotion?” You want to make it feel natural, you want to make it feel earned. And I think that Chris did a really nice job spacing those moments out together so it gave room in-between for the music to allow them to breathe. I’d be nothing without the story and he did such a nice job of developing these relationships through the movie that I was just writing along, and when they needed a nudge to let the audience know that it’s okay to really let it go and feel something, then I could really, you know, get the strings going and let the orchestra do its things. I think it’s the special ingredient in this movie – the relationships. I mean, it’s fun, it’s beautiful to look at, it’s an interesting story and everything; but really, at the end of the movie, what you feel is that attachment to the characters. That’s what Chris is so good at.

AV: You recorded the score with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, which is really brilliant. Can you tell me about your collaboration with that ensemble?

PK: I had actually been there twice before on other films. They recorded some of the original Lord Of The Rings music, they recorded two of The Hobbit scores ; they are a full service film scoring orchestra and they’re incredible. They are a proper orchestra, and the benefit of working with an orchestra that plays together is that they can come together so quickly as an ensemble. It was suggested early on, and I said, “Absolutely!” It’s great fun to be in New Zealand, it’s a beautiful place to visit, and I also think that, personality-wise, they’re a great fit as an orchestra for a film like this because they’re very laid back, they have a lot of fun but they’re incredible impeccable players. We had magical sessions, as you would expect for a film like this. They played their heart. I’d always go back there in a heartbeat, because I love those players and the ensemble. Also, the organization is amazing. They go out of their way to make you feel welcome. You get to record in a beautiful concert hall and just make music, which is a dream! We had a really nice time!

AV: And you conducted it!

PK: Yes. I love being in the room with the players. I think there’s a special kind of energy that you get when you’re in the trenches with the musicians, making music together. I certainly get why some composers prefer to stay in the booth and appeal to a dedicated conductor so they can hear things a little differently in the booth, but I grew up playing in orchestras, so I appreciate being out there with them. I think it just feels more natural, talking about what I need. I am by no means prepared to conduct Mozart’s Requiem. It’s not something I’m interested in doing. I’ve always felt that film conducting is more about being a good communicator than an interpreter. I’ve done the interpretation at that point, I spent so many hours to make the score what I needed to make and, by that time, I’m just communicating what I need. That’s so much easier as a composer if you’re out there with them. And it’s so magical when it all come to life.

AV: So, you’re a composer, a conductor, and also a well-known orchestrator.

PK: When I was in college, I had a fascination with orchestration because I think that, truly, where a piece of music comes to life, it’s in the orchestration of it. I’ve done quite a bit of it in L.A. for other composers early on in my career. So, when I started getting opportunities to actually write my own scores, it’s very hard for me to let go of orchestration completely. I’ll have helpers, because of short deadlines, but for orchestration, my brain works with color. That’s the first thing I see when I hear music. I don’t see notes as much as I see kind of textural things in the orchestra. For instance, the Wish Dragon moves very fluidly, and when I first saw him, my brain went towards motion and color before going to notes. It’s pretty natural for me. As I’m writing, I just think orchestrally. I need help because of time, but I try to do as much as I can on my own. You know, being able to wear a lot of hats is a good thing, but sometimes it can be a curse, because you want to have your hands on maybe more than what is possible. But luckily, on Wish Dragon, we had a healthy amount of time, so I could really dig in to all of the parts and allow myself to really get into each one of them and make the score my own. It’s like I bake the cake and then put all of the frosting on it to make it look nice. French composers are among my favorite because they understood color. They worked in that way. It’s something that’s becoming a little less common in film scoring because it’s so much more about sound rather than color and texture. You know, that comes in waves. That’s the way the world works. If I can do a little bit to bring that back into the world, I’m happy to do it!

AV: Speaking of orchestration, you took part as such in Raya And The Last Dragon, composed by James Newton Howard.

PK: James Newton Howard is a master. He’s one of the greatest film composers. He’s always been an idol for me. So, working with him over the last five or six years as part of his orchestration team has been a dream. I had finished Wish Dragon maybe six months when I got the call that they were gonna need help on Raya. I was a little nervous, and I said, “Man, I’m gonna do a James Newton Howard score about a dragon!” I was feeling so unconfident, but in the end it is a very different film, that takes place in a different area in the world, so a very different score. There’s more bells, some Mongolian instruments. He added some throat singing, too. So, it’s a very different score from Wish Dragon, where we tried basically to stick to the Chinese canon in terms of instruments, whereas Raya is more Indonesian, South East Asia. The lead orchestrator, Pete Anthony, is a genius orchestrator and I adore learning from him. All his team is just amazing, John Kull, Jeff Atmajian and Peter Boyer. How I snuck into that team? I’m not entirely sure still to this day, but I am very grateful. I have so much fun on every score, because working on James’ music is like – it’s all there. We’re just formalizing it, we’re just making it pretty, we’re making very simple traces to make his vision come to life. On Raya, he took a very interesting approach of using a lot of ethnic instruments, but also a lot of synthetic textures as well on top of it. I think it works really well.

AV: You also worked on The Mandalorian, which also proposes itself as an astonishing blending of Western and ethnic influences.

PK: Again, it was Peter Anthony who brought us onto that job. Ludwig Göransson is such a genius with processed sounds and weird, interesting sounds, and in creating these worlds out of these textures you wouldn’t even think of. Obviously, Mandalorian comes from the Star Wars universe where the orchestra plays such a big role. So, the orchestra was always going to be a part of it. The challenging part about that job is that we had to balance an orchestra against all that brilliant madness of sounds you’ve never heard before. They’re coming from things that you know, but he makes them sound like you ‘re not sure what they even are. So, our job is to find a way to make these sounds fit into that world of Star Wars, that kind of grand sweep that you get in all those scores. I think he did such a successful job. For that show it was such an interesting score that fits so well. That’s Ludwig’s M.O. He just pushes the boundaries of everything. It was a very challenging job, but in a good way. He stretches your comfort zone. A lot of orchestrators are traditionally taught. We come from Conservatory education and stuff like that. So, it’s interesting to throw us into that world. You feel uncomfortable at first, but when you work on a full season of a show, by the end of the show, you’re feeling pretty good about it!

AV: A word on Jungle Cruise?

PK: It’s probably one of my favorite scores I’ve worked on with James Newton Howard in the last five years. We really just had a ton of fun. James’ music is just a big blast and I think you’re gonna love it!

With our thanks to Philip Klein, Andrew Krop and Kyrie Hood.