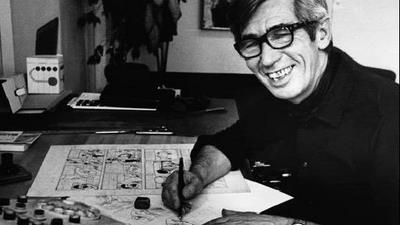

In September 1929, Les Aventures de Tintin debuted in Le Petit Vingtième, a children’s supplement to Belgian newspaper Le XXe Siècle. The comic was from the mind of Belgian artist Georges Rémi, more commonly known by his pseudonym, Hergé.

In Tintin, the title hero is a young Belgian reporter – a career choice Hergé hoped would increase interest among potential newspaper distributors. Solving cases around the world, Tintin is aided by his fox terrier Snowy, the audacious Captain Haddock, the intelligent but hearing-impaired Professor Calculus, and the incompetent detectives Thomson and Thompson.

By the ’80s, Tintin had become beloved worldwide, moving from newspaper comics to magazines and books. Hergé’s tales had been published in more than 80 languages, with more than 350 million copies of the books sold. Meanwhile, the iconic character lit up the silver screen with the stop-motion Crab with the Golden Claws (1947), the live-action Tintin and the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges (1964), and the traditionally animated Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969). Other Tintin adaptations included two stage plays created by Hergé: Tintin in India: The Mystery of the Blue Diamond (1941) and The Disappearance of Mr. Boullock (1941–1942). The Adventures of Tintin also captivated the small screen via several television series, most notably from Belvision (1958-1962), Ellipse/Nelvana (1991-1992) and the BBC (1992-1993).

But it was a critic’s 1981 review of Raiders of the Lost Ark that would eventually catapult Tintin’s stardom to heights previously unimagined. Comparing Raiders to Tintin’s heroic exploits, the review garnered the attention of director Steven Spielberg, who instructed his secretary to bring him several of Hergé’s classic books. While he could not understand French, Spielberg fell in love with the comics’ artwork. Hergé also seemed pleased with the idea of Spielberg directing a Tintin film. According to Michael Farr, author of Tintin: The Complete Companion, the artist “thought Spielberg was the only person who could ever do Tintin justice.” In 1983, Spielberg and his Amblin Entertainment production partner Kathleen Kennedy were scheduled to meet with Hergé, while filming Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom in London. Unfortunately, Hergé died days before the meeting would have taken place.

Ultimately, Hergé’s widow granted Spielberg the feature film rights to Tintin. The director hired E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial screenwriter Melissa Mathison to pen a script, envisioning Jack Nicholson as Captain Haddock. Unsatisfied by the script, Spielberg focused on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, as Tintin reverted back to the Hergé Foundation. Filmmakers Claude Berri and Roman Polanski soon entertained the idea of their own Tintin movie. Warner Bros. negotiated for the rights but lost, unable to promise the “creative integrity” previously offered by Spielberg.

In 2001, Spielberg expressed interest in doing a computer animated Tintin film. The following year, he regained the rights through his studio, DreamWorks. Unlike last time, however, Spielberg planned to serve only as a producer on the film. This idea changed in 2004, when reports surfaced that Spielberg intended to direct a live-action Tintin trilogy incorporating the books The Secret of the Unicorn / Red Rackham’s Treasure, The Seven Crystal Balls / Prisoners of the Sun, and The Blue Lotus / Tintin in Tibet.

During early development for the first picture, Spielberg understood Tintin’s faithful dog Snowy needed to be much more expressive than a realistic dog. Hence, Spielberg called fellow director Peter Jackson to request his visual effects company Weta Digital computer animate Snowy. Jackson, an avid fan of Tintin, explained live-action would not do justice to Hergé’s comics and suggested using performance capture technology. Spielberg agreed, thus making The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn his first directorial venture with the medium.

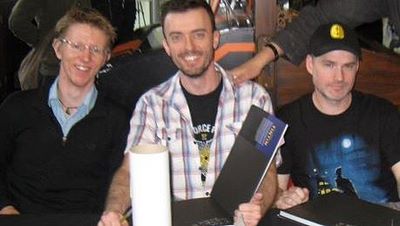

Weta Digital artist Jamie Beard, left, with conceptual designer Chris Guise and

Wayne Stables at a book signing for The Art of the Adventures of Tintin.

Weta mainstay Jamie Beard was brought on board as the animation supervisor for Tintin. Beard jumped at the opportunity to collaborate again with Jackson, whom he had worked with during his initial project for Weta, The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003). Since that endeavor, Beard and the folks at Weta had progressed enormously with performance capture visual effects, from Sonny in I, Robot (2004) to the title character of King Kong (2005) to the inhabitants of Pandora in Avatar (2009).

Passionate about the medium, Beard has made great strides to educate the public about its history and benefits of performance capture, stressing it is more about capturing emotion than motion.

Animated Views: When did you decide to study animation?

Jamie Beard: I’ve been wanting to do animation since I was knee-high. It’s been in my blood for a long time. I had a very, very supportive mother and father who let me study animation. They fed me Chuck Jones. When I wanted to do animation, I took a degree in it at a university; I didn’t do any “normal” degree.

AV: When did you begin working at Weta?

JB: I originally applied to them when I was at the university. But unfortunately, as is often the case, I lacked the industry experience. So I had to work in London for several years. Then they contacted me out of the blue to work on Lord of the Rings. I was a huge fan, so I uprooted and went over to New Zealand, to Weta Digital.

AV: How were you approached to work on The Adventures of Tintin?

JB: I was working at Weta Digital. We had just finished King Kong. I saw we were doing tests for something called Tintin. Well, I grew up with Tintin. But most of the Americans I had worked with had no clue [about the character], which was a blessing in disguise because there was my opening. At that point, the film was only live-action with a CG Snowy. But I went onto it, keen as mustard, to bring the world of Hergé to life.

The film turned into a fully-animated, CG, performance-captured production. That’s the evolution of it. From that starting point, I’ve been involved with the production for about five years. The thing that first got me on it was my love for Tintin. Then Peter was working on it, and Steven Spielberg. It had great writers: Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish. The film kept getting better and better.

Actors Jamie Bell, left, and Andy Serkis sport performance capture suits on the set of Tintin

AV: A lot of folks still haven’t warmed up to performance capture films. How did that affect your work on Tintin? Did it create any concern?

JB: Steven was always very clear on this: we had to honor the world of Hergé. We couldn’t get caught up with any dialogue that had been said before about what films people liked, in terms of the style, because we had a very clear style from the beginning. Steven always wanted to honor that.

As long as we made it look like the world of Tintin, the fans would love it. And that’s been shown, because I have a lot of French friends, and it’s doing very well in France. People, honestly, when they watch this movie, it’s like entering the world of Tintin. And that, for us, has been such a thrill, to see the audience go into that world. Like I said at the beginning, for Americans who weren’t introduced to this – and when we were working on it, a lot of Americans didn’t know the material – they just grew to love it.

AV: You’ve worked with performance-captured characters like Gollum and King Kong. What was it like going from movies with only one or two performance-captured characters to a film where every main character was performance-captured?

JB: Well, you skipped a movie called Avatar. Jim [Cameron] always wanted that to be live-action because, I think, the critical difference there is that Jim could invite you as a person to Pandora, to walk around those avatars. They were “real.” That was the film he made, and it was pretty much live-action, even though the jungles and the avatars are CG.

Going from that to Tintin wasn’t such a big leap. With King Kong and Gollum, of course, there was. But if you put Avatar into the stack, the leap was still great, but it wasn’t as considerable as going from King Kong to Tintin. We did Avatar as well.

AV: Right. I knew Weta worked on Avatar, but didn’t realize you were part of that team.

JB: We were the studio Jim worked with most closely. We did all the facials and characters. It was outsourced as well. ILM did some battle sequences. They sort of did a very small part. But really, Weta Digital was the driving force behind the digital work on Avatar.

AV: You guys did an incredible job. It was unlike what anyone had seen really.

JB: And all that we learned there, we applied to Tintin. It’s the same technology really. But very importantly, the directors approached their films differently.

People often get caught up in the technology and the performance capture. But Jim wanted a real world you could visit with real characters you could see, with Sam Worthington and Sigourney Weaver looking like their counterparts.

But we were coming at Tintin from an animated standpoint. Steven and Peter wanted that to be the case and, along the way, it became an animated film. So we’re using the same technology but in a different way. This is performance capture, where we’re capturing emotions and the fidelity of all the actors and then applying an animated process on top.

AV: Generally speaking, when we see a character in Tintin, how much is the actor’s performance and how much is computer animation?

JB: With Steven tapping into all his talents as a live-action filmmaker, we were able to have him with Jamie Bell moving around the set, doing everything he normally does. But then afterward, as animators, we can look at that performance. Often, we’re coming from two directions here. We’re not just looking at real actors and saying, “How do we copy that?” We’re also looking at the panels in the comic books. That was the case all through the production.

We have two things affecting the way we animate. We’re looking at Jamie Bell’s performance, and we’re also looking at the performance in the comics. So if it’s a bit more “cartoony,” we’d add a little bit more snap to it. Of course, Snowy was completely key-framed, and we had animators adding all the character there.

It’s very easy to think that it’s copying. But when you see a smile on Tintin, and a smile on Jamie Bell, that’s not a one-to-one correlation there. A lot of people think, “Oh, that’s not a big jump.” But it is a huge leap of artistry to make Jamie Bell smile a genuine, heartwarming smile and feel the same on Tintin, even though they don’t look similar. I often equate it to being like when you see a great comedian doing an impersonation. They can endue themselves with all the qualities of the character they’re trying to impersonate, so they have all the nuances and everything. They know the performance.

What we’re looking at, from the actors, is the performance. We copy that performance exactly. We don’t physically copy Jamie Bell, though we did do that a lot more in Avatar where we were trying to physically copy the characteristics of, say, Sigourney Weaver’s face and then put that onto her avatar.

Those two standpoints – those comics of Hergé and the actors’ performances – both feed into how we deal with the data afterward. You can’t say it’s simply just capturing. It’s frustrating for me and the industry where we’re seen as just motion-capturing. Motion-capturing has no emotion. Performance capture is where we capture all the details. Then we look at the comics and see, “How do we get all of that feeling that Jamie has got, into our Tintin character?” Often that means tweaking smiles to make it work just on Tintin’s face. We can add more snap if the Thompson twins hit a lamp post; we can have a lot more hang time in the air. They can fluff around with their fingers more. We can add more performance on top of it. It’s an additive process.

AV: The film was made with IMAX 3D in mind. How did that affect your process?

JB: No differently than any other tool in the filmmaking arsenal. You can look at new technologies and get quite bamboozled with them and how they go into your film. In a film, if 3D jolts you out of the experience, that’s a bad thing. If it pulls you into the film, if you don’t notice it in a way, or if it enhances the spatial relationship, you really feel like you’re there.

It’s that way with editing, costume design, lighting – if a light is misplaced or put into the wrong area, if it’s clumsily dealt with, it will jolt you out of the story. With all of these elements, including stereo and 3D, if it’s dealt with in a clumsy way, it will jolt you out of the story. Then suddenly you’ve broken the reality of watching this real place and this real story unfold in front of you.

I think if you keep that in the back of your mind, you should have no problem with any new technology that comes your way. You just need to remember, it’s an immersive experience of a story you’re wanting to watch.

To surprise director Steven Spielberg, producer Peter Jackson

appeared as Captain Haddock in a visual effects test for Snowy.

AV: Now that you’ve worked with Spielberg and Jackson together, how did their directing styles differ?

JB: It’s funny, because it’s so rare that you get to work with great directors like either of them on their own. I went to New Zealand, because I could work with Peter Jackson. But then you get a film where you can work with both of them. To watch them collaborate together was actually one of the best parts of this project for me, and for everybody, because they are so collaborative.

I’ve heard a great quote in the media, which is that Peter is kind of the Captain Haddock and Steven is sort of like the Tintin. For me, that rings true, because Steven brings an energy – a childlike enthusiasm – even on set. Peter said this himself, he just comes to the set like it’s the first thing he’s ever done. He’s not jaded; he’s full of ideas. He’s got thousands of ideas on set. Peter is kind of an archic and a little bit mischievous. Seeing that come together has been great, and seeing them do that to their film and the characters has been wonderful.

AV: Are you going to be the animation supervisor for the next Tintin movie?

JB: You know, I love Tintin. I don’t know what the plans are. I’ve heard some stuff being talked about from Peter’s side.

At this point, I’m just educating as to the sheer amount of work the animators put into this film. I’m really happy to talk to you, so that I can share our experience. It was slightly difficult to hear that people think we’re doing an easy process of just capturing motion and sticking it on screen. It goes against all the hard work the animators have done.

I’m really trying to champion this, for all of the team that worked on it. That’s my prerogative at this point.

The Adventures of Tintin is now playing in theaters nationwide.

The Art of the Adventures of Tintin

is now available to order from Amazon.com.

Our deepest thanks to Jamie Beard and Julie Tustin at Paramount

Jamie Beard image is courtesy of WetaCollectors.com