Amblin/Wingnut Films for Paramount/Columbia (October 26 2011), Paramount Home Entertainment (March 19 2012), 1 Blu-ray and 1 DVD combo set, 107 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition 2.40:1 widescreen, DTS-HD 7.1 Master Audio, Rated PG, Retail: $44.99

Storyboard:

Combining three of famed Belgian artist Hergé’s original Tintin graphic novels, director Steven Spielberg and producer Peter Jackson’s fabulous adventure movie brings the young intrepid investigative reporter to the screen with genuine panache!

The Sweatbox Review:

We Belgians (yes, I was born there before moving and swapping countries very early on) don’t often get a lot of credit for our achievements, and I have never really been able to quite work out why. While other countries may be famous for one major contribution to the fabric of the world, and some struggle to come up with even one reason to be remembered, Belgium – which is an odd amalgamation of Holland and France whichever way you look at it – is actually famous for several things. Apart from the creation of many notable artistic works (including those by Brueghel), there’s the fine and justly famous tradition of rich chocolate, of course, but it’s in pop culture where the legacy is also a surprisingly strong one: the Smurfs, Lucky Luke, the lineage of Asterix and, naturally, Tintin have all been born from the minds of artists (or helped along their way) from this otherwise mostly overlooked and much chuckled at country.

Created by Georges Remi, under his pen name Hergé (the reverse of the French pronunciation of his initials) in 1929, The Adventures Of Tintin originally ran as a syndicated comic strip in the junior section of a weekly Belgian newspaper. On completion of each adventure, typically serialised over twelve months, the publisher would assemble the strips into a hard-bound comic book form, known as an album in Europe, to create a graphic novel-styled package: the first of these was Tintin In The Land Of The Soviets. Hergé continued to write and draw the Tintin series over his lifetime, the stories eventually overwhelming other characters he initially created and becoming his main source of creativity and income.

Although there had been several attempts to bring Tintin and his colorful cast of companions to the screen, including a 1940s stop-motion film and two live-action features in the 60s, the only really authentic (and Hergé approved) version was an animated series produced by the Belvision Studios, also known for their Asterix and Lucky Luke features. Mirroring the way Tintin had debuted as a strip before being compiled as feature-length stories, Hergé’s Adventures Of Tintin began as a five-minute show for television (often criticised for differing from the books too much) before some of the 104 episodes, dedicated to The Calculus Affair, were combined to create a feature film.

Two more followed: Temple Of The Sun (based on the books that will form the basis for the second film in this new intended trilogy) and Lake Of Sharks, both of which remained true to Hergé’s distinctive line art even if Sharks (as were most of the Tintin films) was an original story, later adapted into comic strip form. Much more faithful was Nelvana’s 1990s animated series, which split each album into two episodes, but for me the artistry couldn’t quite capture the Hergé spirit. His is a quite indefinable one to delineate, because while the stories were set in the real world, albeit approximately during the year they were published over time, meaning that no one ages, the characters themselves and the situations they find themselves in are as fantastical as they come!

So it’s a brave and yet ultimately justified and unavoidable choice that when Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson joined forces for their long-cherished dream of bringing Tintin to the screen, it would be through the medium of animation, tinted by the unique brand of motion-capture techniques that Jackson’s Weta Digital effects company had perfected through Gollum in his Lord Of The Rings trilogy and the mighty ape in the 2005 remake of King Kong. It would have been interesting to know what Hergé, who died after 23 Tintin adventures (leaving a 24th unfinished) would have made of it: certainly he would have been pleased with Spielberg as director. When he saw Raiders Of The Lost Ark in 1981, two years before his death, Hergé deemed Indiana Jones the “son of Tintin” and the director the only one capable of bringing his stories to the screen.

Spielberg, on the other hand, had never heard of the Tintin stories, but quickly educated himself and, by mutual agreement with Hergé’s estate following the artist’s passing in 1983, signed a deal to create a movie series based on the books; a deal that ultimately lapsed with Spielberg’s hopping between further Indiana Jones films and more personal pictures. Meanwhile, lifetime Hergé fan Peter Jackson was eager to strike Tintin off his wish-list of properties he wanted to adapt, and so the two decided to team up for a trilogy of films, Spielberg to direct the first one with Jackson to produce, and the roles to switch for the second film (details for the third remain sketchy, with nothing set in place). Without resorting to padding out Hergé’s stories, it was decided to combine two, although elements from a third eventually found their way into the film.

Calculated to introduce not only Tintin and his faithful fox terrier Snowy but also a number of other recurring series characters, I have to say the resulting film is probably the best time I’ve had in a movie theater for a long, long time! Right from the opening frames – a distinctive silhouetted title sequence that smoothly carries Tintin from the “printed page” to animation without giving the look of the characters away – one can tell Spielberg has upped his game tremendously from his last such action-adventure, the sadly lacklustre Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull, perhaps as a way to compete with his producer colleague. Indeed, one wonders if frustration with how Crystal Skull turned out might not have been the catalyst for the director to try his had at similar fare without any Lucas influence?

Jackson persuaded Spielberg to create the film digitally, after a test showed that Weta had cracked the “uncanny valley” curse that plagued motion-captured films produced by Spielberg’s one-time protégé Robert Zemeckis. But whereas Zemeckis’ films (Polar Express, Beowulf and A Christmas Carol among them) simply transposed his mo-cap suited actors’ movements to their digital doubles, Weta’s process, honed on Gollum and Kong, was to simply use that data as reference points, scrubbing the performance and keyframing the characters so that they worked in animation and ironically therefore appeared more realistic. The outcome – as showcased in the opening scene – is phenomenal, and raised an audible gasp from me when I first saw the film.

Opening in what we must assume is a non-descript Belgian flea market (Brussels in the book), we find a local artist at work, drawing a portrait of a young man with his back to us. The artist, of course, is Hergé, in a perfect tribute to the man and his work, and most fitting in being the first face we see in the film (the 1930s feel also reflecting the era of Tintin’s debut). He holds up his work and, of course again, it happens to be an image of Tintin, whose image he proclaims to have captured quite nicely. Tintin turns to show Snowy – and cue the shot that had me gasping. Here we see an almost true, flesh and blood synthespian depicted with all the near-photorealism of a film which has somehow managed to find a living actor and cast him in a movie. For the next few minutes I marvelled at the tangible textures, the very real feel of the scene, and the sheer immense detail of the thing, all the while moving along without calling attention to itself and without being overwhelming.

The rest of the film follows suit: when Tintin (performed by Jamie Bell) arrives back at his apartment and removes his coat, the effect of such a simple gesture is awe-inspiring onscreen, his movements feeling very real, yet animated, while the coat falls to the ground with something approaching relish. It’s these very little things that go a long, long way to making The Adventures Of Tintin vastly enjoyable in many subtle ways. Most of this is down to the performance cast, who also voice their characters, and what a line-up it is: Andy Serkis finds his sea legs as boozed-up Captain Haddock (surely much better and less hammy than a live-action Jack Nicholson would have been in Spielberg’s earlier 1980s version), and British comedy team Simon Pegg and Nick Frost (Paul) put on their best upper crust accents to portray detectives Thomson and Thompson.

A revelation – to me at least – is Daniel Craig, a terrific James Bond to be sure, but often as one-note in his other performances. Here he seems to be having a little fun with his bad guy role – vastly expanded from Hergé and, in fact, largely replacing another villain that goes completely missing – and gives the character some real nuance as well as a somewhat flamboyant, theatrical flair. His body language is also delicious, and here’s where Jackson’s Weta bounds ahead of Zemeckis’ ImageMovers brand of motion-capture. In those efforts, the data was pretty much translated to the digital puppet, meaning very good pantomime actors had to be in place and able to push their performances further so as to “move” their digital incarnations authentically.

With previous thespians providing intricate performances, these didn’t transfer well to the digital puppets, unless the likes of Andy Serkis (Gollum, Kong and Haddock here) – actors who understood mo-cap performance – were in the zone. Jim Carrey put in a brave attempt in A Christmas Carol, but again the data processing hampered the actions, particularly in the face movement. But where Weta triumphs is in then in essentially disregarding those performances, using them instead for the basis of the keyframe animators’ performances, augmenting what was shot “for real” with additional tweaks that, in the case of Craig’s villain, turn what could have been a brilliant but too subtle performance into a tour de force that delivers a truly believable kind of “villain we love to hate”. Indeed the first time I saw the film, I actually thought it Serkis and Craig’s roles were reversed: it was only on staying for the credits that I realized what great work both had delivered.

The top-notch values stretch far into the film: the traditionally computer animated Snowy is as realistic as any live-action dog, even if he is clearly a “cartoon character” (ironically, it initially seemed to me that this was a “live-action Tintin”, with an animated dog placed into the world a la Scooby-Doo, and on further screenings this still does feel the case, for me). Spielberg’s long-time musical collaborator, the great John Williams, also provides his best score in a long while, easily besting his recent Indiana Jones (a so-so return to past glories for a terribly disappointing film) and the concurrently released War Horse, where Williams seemed to mix up the south of England’s Devon for Ireland.

But here, there’s a fantastic return to jaunty little riffs that he used to engage in during his 1970s and 80s golden period, combined with the big adventure that only a rich and full orchestra can provide. Tintin’s five-note motif may not be as instantly recognizable as Indy’s march, but it lends great character to the intrepid reporter and evokes the same kind of Saturday matinee serial feel that was so sorely missing from the fourth Indy movie. Actually, although it was written by another composer, I was reminded by the tone of Bruce Broughton’s music for Young Sherlock Holmes, the tricksy, infectious, impish and slightly mischievous main theme bringing back the feel of Williams’ Catch Me If You Can title suite and setting the scene just as perfectly for what is about to follow.

And I can’t quite stress enough just how much fun what follows is! As written by Stephen Moffat, the British writer who has given such new life to the country’s recent Doctor Who revamp as well as the contemporary twist on Sherlock, and then polished off by Edgar (Scott Pilgrim) Wright and Joe (Attack The Block) Cornish – two directors in their own rights – The Adventures Of Tintin certainly takes liberties with Hergé’s source, but does so in service of creating a valid film adaptation as opposed to slavishly honoring the material but not reaching the albums’ heights in terms of tone and spectacle. Just as Mike Newell did with the fourth Harry Potter book, the filmmakers here have taken what inspiration they need from the page, and made a great film; one that retains all of the writer’s original spirit and intent, and yet serves up elements that should keep old fans interested and new ones excited.

Based mainly on the album – the eleventh in the series – that gives the film its sometime-subtitle, The Secret Of The Unicorn uses that story as its main plot element, although several characters, in particular Haddock, have found themselves utilised in alternative ways and some (the Bird Brothers, as noted above) removed completely. Likewise, in the slim pickings from the book’s official sequel, Red Rackham’s Treasure, the hard of hearing Professor Calculus is also AWOL, perhaps waiting to be introduced in the next film. Haddock’s own introduction has been lifted from a third album, The Crab With The Golden Claws, as well as a handful of other sequences, and although I can understand the infuriation of the purists who would have liked straight-forward adaptations, can’t help but think the filmmakers have taken the right path here in providing a uniquely new twist on stories that have been translated numerous times before.

All of which leads me to feel saddened at The Adventures Of Tintin’s lacklustre US box-office and no-show at the Academy Awards. Thank goodness, then, for Europe and the international audiences that made the film a giant hit before it even opened in the States (and thus ensuring the proposed sequel would go ahead) and some of the other nominating bodies that did award the film with Best Animated Feature gongs (the UK’s Bafta and the Golden Globes among them). Tintin provides the kind of high-quality film experience that has been all too missing of late, and returns Spielberg to the top of the tree in terms of sheer technical filmmaking talent (the single-shot chase scene three-quarters of the way through is the director at his best, providing both the best action sequence of the year and throwing down the gauntlet to see what Jackson can come back with).

It really is exhilarating, exciting and pacy stuff, never lacking in interest or intrigue, while offering the kind thrills modern audiences expect along with more subtle angles (just watch Tintin’s face when he exclaims “Great snakes!” as an idea literally forms in his brain) and a warmth that took me back to the great Amblin Entertainment films (a clear sign Spielberg was personally committed to this is in him using his own production company to produce the film as opposed to releasing it through DreamWorks, even though this resulted in a potential bit of self-competition up against Puss In Boots). I’m sure I’ve probably set it all up too highly, but I’m also sure that both long-time fans and newcomers to Hergé’s world should find themselves enjoying Tintin’s adventures to the full, and will hopefully make the next Adventures Of Tintin an even bigger hit!

Is This Thing Loaded?

With the two prominent filmmakers involved in bringing Hergé’s characters to the screen each having somewhat opposing views in how their films are dissected on home video (Spielberg prefers not to comment on his films and holds back some of the magic, while Jackson is pleased to offer multiple commentaries and a film school’s worth of supplements revealing each and every tiny detail), The Adventures Of Tintin arrives on disc with a very reasonable, over 90-minute selection of behind the scenes material that is not only more than satisfactory due to long-time Spielberg documentarian Laurent Bouzereau’s comprehensive coverage but also surprisingly all-encompassing despite its brevity.

Topping the list is Toasting Tintin: Part 1 (1:24), a brief snippet from the beginning of shooting in which Spielberg reads words of blessing on the project and its crew from Hergé’s widow. A series of behind the scenes featurettes continues delving into the background of Spielberg and Jackson’s discovery of the series and a full exploration of their movie’s making. The Journey To Tintin (8:54) is a terrific look at the project’s long gestation, from Spielberg’s original deal with the Hergé estate, through Jackson’s literal and quite brilliant portrayal of Haddock in a test shot designed to sell the CG Snowy in a live-action film, through to how the two men worked together on the “set” of the mo-cap stage and their erudite approach to the material.

The World Of Tintin (10:46) has actor Gad Elmaleh explaining how Tintin’s name should be pronounced authentically (in French it sounds more like “tantan”, the way my Dad used to say), as well as a look at Tintin lore, including how his famous hair quiff came about. Again, the great level of thought that went into the film is clear, and the personal connections obvious: where else would you find Peter Jackson described as a second unit director!? The movie’s casting also gets some very nice attention in The Who’s Who Of Tintin (14:18), which also works as an intro primer to Hergé’s characters and what the actors and characters got up to during their joint adventures.

The movie’s development is further revealed through Tintin: Conceptual Design (8:38), in which none other than Weta’s Richard Taylor takes us through the process of how the Weta wizards actually took Hergé ’s comic panels and transformed them into “real”, believably three dimensional characters and environments. Not only is there a great amount of healthy talk about preserving the original intent, but we get to see some simply wonderful photo-real Weta depictions of Hergé art as well as how these became the settings for the actors to play against in the mo-cap stage. Which brings us seamlessly to Tintin: In The Volume (17:54), showcasing the results of all that preparation as the cast and crew “film” the movie’s character performances.

Although most mo-cap movies reveal their process in this way in their disc supplements, this is more engaging than most, since it offers up a very cool first hand account of Spielberg and Jackson’s working methods (the latter sometimes “co-directing” from his base in New Zealand). Naturally any potential debates on creative choices remain off camera, but there really does seem to be the feel that everyone was very polite and all in a creative unison in their artistic endeavors. I was also intrigued to see some changes in the process: instead of tiny reflective balls placed intricately on the actors’ faces, a new “mask” system means quickly and accurately applied paint makes the process faster, and the real-time CG rendering that allows the actors to instantly see their performance is phenomenal.

There was one character in the movie that was keyframe animated from the start, and that was Tintin’s faithful fox terrier dog Milou – to give him his original French name. Better known as Snowy: From Beginning To End (10:11, or The Full Tail as described on the sleeve) takes a look at the history of the clever pooch and how he was integrated into the mo-cap data. The rest of the movie didn’t purely rely on the mo-cap data either, Weta’s process then being to essentially scrub that information and use it only as reference to keyframe the characters and animate their movements and, particularly, their facial expressions traditionally so as to make them work in the animation medium. Animating Tintin (11:00) explores this process briefly, also touching on the fully animated environments the characters inhabit.

It’s understandable that The Adventures Of Tintin’s supplements should focus on these technical challenges and achievements, but it’s very nice that Williams’ exuberant music – his first for an animated film – is given a chance to shine in Tintin: The Score (7:01). The composer is one of those movie legends that consistently turns out great work, and even if some of his more recent scores (mostly retired, he pretty much composes exclusively for Spielberg nowadays) haven’t hit the high-notes of late, Tintin restores his reputation as simply one of the best. I didn’t care too much for his music for War Horse, it not really knowing when to shush, but Tintin is a different beast entirely, and one of the main reasons the film doesn’t feel “Indiana Jones-lite” is because of Williams’ full, rich, golden period-harking score that gives Tintin its own identity, and Williams’ attention right down to the individual instrumentation he uses is clearly why he’s still top of his game, and why the music here gave him yet another Oscar nomination!

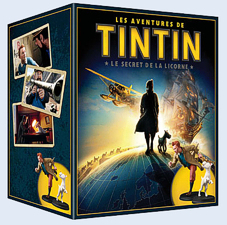

Collecting Tintin (3:58) turns the attention on some of the merchandise created for The Adventures Of Tintin and, in particular, Weta Workshop’s highly-praised Collectible line. It’s a little promotional, of course, doing little other than showing off how cool these collectibles are when what might have been nice would have been to see how they were created from the CG renderings. Mostly, however, there does seem little point to including a featurette on these figures when there isn’t any kind of deluxe box set that includes them in the way Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings or King Kong offered. The French chain Fnac is offering the Tintin and Snowy combination showcased here along with the Blu-ray, but one would have to be a big fan with the kind of hefty import tag it would no doubt carry, which only makes this peek at the characters even more frustrating, though there’s no doubting the intricate work is fantastic.

Lastly, Toasting Tintin: Part 2 (3:12) joins the crew at the production’s wrap celebrations, coming full circle to end the disc’s supplements. While the inclusion of one or two theatrical trailers would have been appreciated, or the appearance of a concise TV special a plus, what really feels “missing” here is any reference to the almost mythical 20 minute test reel that convinced all involved that Tintin could be made realistically as a motion-captured film. With Spielberg and Jackson joined by fellow 3D mo-cap filmmakers Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, the test sounds as if it was really something and would have made for fascinating viewing, alongside some of the other early concept shots, live-action or otherwise.

A separately sold standard definition disc includes three of the featurettes above, but the enclosed DVD here doesn’t include anything but the feature and a number of trailer previews, including those for the about to be reissued Titanic, an anti-tobacco spot, Madagascar 3, Puss In Boots, the Indiana Jones Trilogy on Blu-ray, and Hugo: inexplicably Oscar bait when Tintin barely managed to garner just one nomination, not for Best Animated Feature but for Williams’ Score; Weta was also nominated, for their Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes visual effects, again with Serkis performing.

Case Study:

Also available as a 3D Combo Pack, this is the regular Blu-ray, DVD and Digital Copy edition we’re looking at here, which is exactly the same package minus that third dimensional disc. A slimline BD case is held in a non-glossy or embossed slipcover (the 3D edition adds some light embossing) that replicates the sleeve underneath, while inside is an insert for other Paramount titles and the required code for the UltraViolet Digital Copy, the still-recent new term for downloadable file versions of movies as opposed to including a physical disc. While UltraViolet sounds pretty cool in name, that’s all it is: just marketing speak for a streamed edition of the film for playing on portable devices.

Also available as a 3D Combo Pack, this is the regular Blu-ray, DVD and Digital Copy edition we’re looking at here, which is exactly the same package minus that third dimensional disc. A slimline BD case is held in a non-glossy or embossed slipcover (the 3D edition adds some light embossing) that replicates the sleeve underneath, while inside is an insert for other Paramount titles and the required code for the UltraViolet Digital Copy, the still-recent new term for downloadable file versions of movies as opposed to including a physical disc. While UltraViolet sounds pretty cool in name, that’s all it is: just marketing speak for a streamed edition of the film for playing on portable devices.

While this does seem to save on including a redundant disc (and around $5 on cost), distributors are still trying to push UV and so the promotion takes up a lot of real estate on some sleeves. This one doesn’t look too ugly, but it’s not the most attractive either, with the 3D package taking up more room to promote that technology. Much better, although costly and missing the 3D disc, is a European edition that includes Weta’s Tintin and Snowy collectibles [above, right]. Perhaps had the film been more successful in the States it would have gotten the same treatment, but for those tempted, that set can be found as an exclusive to the Fnac chain in France.

Ink And Paint:

Optionally presented in 3D in theatrical release, naturally there is the 3D disc edition to choose from, too (for an extra ten bucks), but in all honesty I’m not sure the added depth really did anything for Tintin in the way some other animated films might have benefited. I saw the film theatrically twice in 3D and once “flat”, and even on the first viewing I didn’t come away feeling as if the third dimension added anything significant. On seeing the film flat, and again in that format in this particular disc presentation, one might reason that certain scenes or shots might look “better” in 3D, but I really didn’t find that was the case here.

And the image theatrically was so sharp and detailed thanks to the incredibly lavish world Jackson and his Weta team created, that I did find I preferred the brighter images without the 3D specs in place. But one simply can’t call this “flat” at all, the frames having terrific life and vitality to them that further blurs the line between animated, near photo-realism and the real world. This shows off the astounding production design and intricacies of the simulated props and clothing to astonishing effect, providing a new demo experience – the film’s breathtaking, single-shot motorcycle chase – that’s second to none, be it animated or live-action.

On the enclosed DVD, I hate to say it, but the faces look a little more waxy and unconvincing, with the transfer all too indicative of recent BD and DVD combos in which the standard definition discs seem to be getting softer and softer in general. The DVD disc structure also had me confused when I went to see how much of the disc the movie used up (there are no other extras save for some previews), since it looks like there are multiple editions of the movie contained herein with, it seems, the alternate The Secret Of The Unicorn title an option in some cases. Strange, but then again I guess this is another “one size fits all” disc that is designed to travel around the world under different distributors.

Scratch Tracks:

Perhaps predominantly choosing British accents so as to suggest the classic nature of the original stories without resorting to phoney – and maybe off putting – French tones, I felt the casting on Tintin was as perfect as the animation. I’ve spoken already about how Jamie Bell brings a solid characterization to the boy hero, basically sounding English enough without making Tintin a British character exactly, with the rest of the voices suiting their personalities: Craig’s nefarious villain, Serkis’ Scottish brogue-tinged Haddock and others providing an authentic sound.

As captured and re-recorded on the mo-cap stage, the real marvel here is not how clean the sound is but how “real” it sounds mixed into the various atmospherics: despite all being voiced inside, one totally accepts hearing Tintin and Haddock in the desert or during the motorcycle chase without even thinking about it, an important part of animation production that often gets overlooked. Likewise the spot effects and Williams’ Academy Award-nominated music play great parts in almost making us forget the soundtrack, presented here in faultless DTS 7.1 Master Audio and a mix of other Dolby options (give the French track a go to get an even more “authentic” feel!).

Final Cut:

Tintin was, since my Dad was Belgian himself, a very important component of growing up for me. Before complete English translations of the albums became available, I used to read the original French editions (where, sometimes, Tintin’s name would be split as Tin Tin), or have them read to me, and so the character and Hergé’s world is close to me for many other reasons than just being great adventure stories. I remember Dad becoming emotional when the news of Spielberg’s optioning the rights reached us in the 1980s, for although we had loved Indiana Jones’ exploits, he was worried that the director would Americanize the property too much. I lost my Dad in the early 1990s, but I can say that I believe he would have enjoyed this end result, a fusing of authentic Hergé and Spielberg.

Paradoxically, Tintin is an old-school action adventure in the grand style brought to life via state-of-the-art technological moviemaking processes, and the result is the kind of skilled and successful melding of story and tools that such recent returns to past glories as the Star Wars prequels, Superman Returns and Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull should have been. In Spielberg, Jackson has found the kind of intuitive, quick and clever mind that Tintin himself has, while to Spielberg, Jackson is clearly Haddock, providing him with the an alternate view on things as well as the means to carry on into new waters. Theirs is a mutual double-act that seemingly knows no bounds.

The effect is truly astonishing, and there’s really no other way Hergé’s caricatured but detailed world could have been so faithfully realised on film. Yes, the plot borrows heavily from various books in the series as opposed to offering a straight adaptation of one or two of the albums, but then no Tintin movie before it had ever been as totally faithful either, even the ones that Hergé was involve with! But what stays true is the tone, the likenesses of the characters – again, only possibly through animation, with mo-cap providing the unique new approach seen here instead of repeating what we’d seen before – and the honest Hergé spirit, creating a “real” world that’s still as surreal and stylised as anything on the page.

It’s as just about as faultless a combination of talent and technology, and Hergé’s property the absolutely precise property to receive this kind of joint attention and treatment. For all the depth, it’s true that some sly satire is overlooked, and one can think about a supposed Hergé/Haddock connection all they like, but this is about as successfully perfect a movie translation for the boy investigative journalist as one could wish for. I thought of my Dad more so than in any other movie for quite some time, and I think he would have been thrilled, but as for those still questioning some of the movie’s choices, well, all I can come back with is the fact that Hergé himself picked Spielberg as Tintin’s movie custodian all those years ago – and great snakes if he wasn’t right!

| ||

|