Walt Disney always had a soft spot for the Seven Dwarfs – and even his successors show the same tendency: after all, isn’t it Dopey who dominates the Team Disney building in Burbank? A major element of the success of the 1937 classic, they were instrumental in the survival and the development of the Disney brothers’ studio.

As Walt stated at the time: “The seven dwarfs we knew were ‘natural’ for the medium of our picture. In them, we could instill boundless humor, not only as to their physical appearances, but in their mannerisms, personalities, voices and action.” In order to do so, he took extra care of their development as true characters, as unforgettable personalities.

And that’s the story we were fortunate to hear from Lella Smith, Creative Director of the Walt Disney Studio’s Animation Research Library, during a memorable roundtable discussion set recently by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment to celebrate the release of the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Diamond Edition.

Roundtable Interviewer: How would you say Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs distinguished itself so that it really became the international phenomenon we know?

Lella Smith: Well, I think, my personal opinion is that it was because Walt Disney was able to imbue the characters with so much feeling and with a real sincerity and humanness to them so that you really related to them, my personal feeling. You know, and that was a real challenge for the artists because they had only done animals and it was hard for them to show these emotions.

So they spent many, many hours developing the characters to have human qualities that we could relate to. And there would be a time, for example, when artists would have to think I’m used to drawing a dog or a horse falling off a cliff, what would happen to a human if they fell off a cliff. You know, certainly they would probably get killed, so they had to, you know, they had to rethink the way that characters responded in animated films.

I think, too, that by the minor changes that were made to the story, which incidentally, Walt was sometimes criticized about, I think the story become a better story. I mean, the fact that Snow White was a stepdaughter, not the daughter of the queen from, you know, if we were talking in the Grimms’ version. I don’t know the silent film versions well enough to address those questions, I’m really sorry. But I can compare them to the Grimms’ version.

And I know that Snow White in the original Grimms’ version was seven-years-old and the queen was her mother. And Walt Disney said, well, you know — I just can’t deal with the mother killing Snow White. So I think there were subtle changes that were made to the story that made it something people could relate to.

You know, the queen in the original version died a painful death dancing in shoes that had been put on hot coals. Well, Walt said, let’s have the queen fall off a cliff early on before Snow White is awakened by the prince so that they can celebrate the love that is created between these two individuals. So I think those things made it a stronger story.

RI: How did the artists work to achieve emotion and feeling into the film, since that was such a key part of what makes this such a landmark film for animation?

LS: I think they went back to motivation for example. And they also tried really, really hard to make the characters relate to each other in a way – by their gestures, by their facial expressions. If you look at animation drawings of the princess, her face is so sweet, how could the prince not fall in love with her? So, you know, they worked really hard at these subtle things that made the story very special and motivation was a very important part of it.

They realized that the queen, who was extremely beautiful, was even more sinister because she was beautiful. And so if you had feelings of looking at the queen and thinking, oh my gosh, this is a beautiful woman, when she was evil, she was that much more evil. So I think there were decisions that they made about characteristics of the characters and then the way they were drawn that helped those feelings.

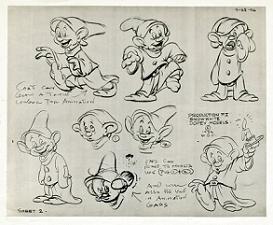

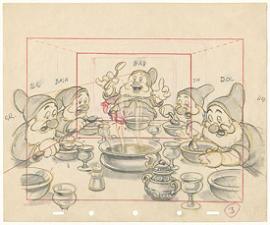

The fact that each dwarf is a definite individual is one of the landmarks of the picture. One thing that’s important to mention is that you can tell which dwarf is which, I mean, just by looking at them, there’s something that’s going to tell you that’s Dopey on the left and Sleepy on the right, we’ve got Grumpy next to Sleepy. There’s something about each dwarf that will help you immediately know which dwarf is which.

So, that was one of the main frustrations that the folks working on the film had in the beginning. Dave Hand who was Directing Supervisor kept saying to the artist, “I can’t tell them apart, we’ve got to work on a way to tell the dwarfs apart.”

RI: It all started… with names. How was the process of creating the personalities of the dwarfs like?

LS: Many, many, many, many names that were considered.

We had Jumpy, Baldy, Grumpy, Happy, Doc, and Sleepy… Well, the thing that is important about this, it was the result of a story meeting that occurred on October 9 in 1934 where Walt Disney actually said, “Let me tell you about the dwarfs. Here are some sort of descriptions of who those Dwarfs are.” So at that time there was a Jumpy and a Baldy. They ultimately were replaced.

But it kind of told you characteristics of each of the Dwarfs. And, you know, Sleepy falls asleep at the wrong time, a fly bothers him, long lanky type, untidy, one sock down. And Jumpy was supposed to be a goosy type, talks fast, mixes up his words: he’s asleep in my sled…she’s asleep in my bed.

So each one have a description. They were all to be Wheezy, Stubby, all behind or last in processions, fatter and shorter than the rest. So, you know, I think Walt understood early on that these would be the guys who would steal the show. And he needed to have them in the film for a number of reasons, not the least is which was that they still wanted the Seven Dwarfs for humor as the film can be somber in places. He felt that the Dwarfs would give the opportunity to have comic relief and also would be characters that people would relate to.

I think initially he thought that Doc would be the leader of the pack, but in the end it was Dopey who stole the show. And everybody wanted more Dopey. Here are some of the names that weren’t chosen: Hicky, Gabby, Nifty, Sniffy, Lazy, Puffy, Stuffy, Shorty, Wheezy, Burpy, Dopey, Dizzy, and Tubby.

And the names were supposed to inspire the drawing and the characteristics of the Dwarfs so that, what would you do to draw Nifty? You know, it would be difficult to draw. And how would you draw Stuffy? It comes to mind but it might get old soon. So they were not among the final choices.

I can’t tell you how interesting it is to read the story notes from the many, many, many meetings that were held between ’34 and ’36 to define the characters and to define how they would move, what their reactions would be. And when you have the really wonderful artist like Bill Tytla and Freddie Moore, they would be saying, ‘Well, you’ve got to get down to how they would think, that will affect their action.’ And then you have Dave Hand, Supervisor and Director saying, “No, no, no, I’ve got to know how they’re going to move so I can recognize them.” So they went back and forth and back and forth. And many hours of long discussions to decide each Dwarf.

RI: How did the Dwarfs come to work in a mine?

LS: There’s a drawing of the Dwarfs as sailors on a dream ship, I can’t tell you why that is, but it’s pretty fun with the sailor hats and the beards. They look pretty grumpy, you know. And depending on the story that you read, the other versions of Snow White, the Dwarfs did not work in a diamond mine in the other versions. But Disney had them work in a diamond mine, which added a certain grubbiness to them which was also in contrast to the descriptions that existed in earlier versions of the Dwarfs being very meticulous.

So Walt Disney thought it would be much funnier if they, you know, didn’t take a lot of baths and worked in a diamond mine and their house was a mess and Snow White comes to the house and, you know, helps them get their lives together. That wasn’t the case in the Grimms’ version.

RI: You mentioned Dopey. Can you tell us more specifically about him?

LS: At one time, Dopey was actually drawn as a very tall, heavy set character. And an older adult like the other dwarfs. But they realized that he was not coming off the way they wanted Dopey to come off. They wanted Dopey to appear very childlike, very innocent, very fun, and with him being a grown man, that wasn’t what was happening. He was just coming across as being slow. And they didn’t want to make fun of anyone.

So they changed Dopey to be the one character who was not older. You see, he doesn’t have a beard. He’s very childlike. And he changed quite a bit in his design.

Walt Disney was very, very careful in the defining of the dwarfs, and in defining of Dopey in particular, that no one take offense. They really wanted him to be childlike and innocent and they enlarged the size of his ears and enlarged the size of this cap so it fell down over his head. And, you know, they made him younger so that he would be a more interesting character.

RI: Grumpy is also a very interesting personality.

LS: It’s always interesting for me to see how much Grumpy’s personality changed. He was the most sophisticated characters of any of the Dwarfs really because he started out wanting to get rid of Snow White, sort of a misogynist. Grumpy was not going to like her and he was not going to let her stay. But you’ll notice that as the film goes on he likes her more and more and at the spot when the animals come to tell him that Snow White is in trouble, it’s actually Grumpy that says let’s go save her.

So he does a complete turnaround and he was a lot of fun for the animators to work on. And he had a lot of animators work on him. He was mostly worked on by Bill Tytla, but he was also worked on by Freddie Moore, Dick Lundy and Fred Spencer. Bill Tytla was one of the greatest animators who worked at Disney and he enjoyed the challenge of working on Grumpy.

RI: The animators also relied on human models for inspiration. How did that come about?

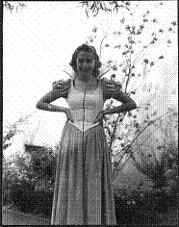

LS: It was something that Walt Disney had kind of played with before, but when Snow White came along and they were trying to draw the human figure, they appealed to it to a wider extent. Remember they had been used to drawing animals. And when you start drawing a real girl’s hand, you’ve got to know how to do that. So the thought was to go to someone like Ed Collins, have him come on to the studio, dance around and move like the dwarfs and let the artists watch it.

Well they did that and what was interesting was that Freddie Moore took the film home that night, played it in slow motion and then speeded it up and then slow motion and speeded it up and that’s kind of where the real knowledge about squash and stretch came from. Because, you know, they just realized that when you extend your hand in reality you extend your hand quite a ways and there’s a long amount of action that goes into that gesture and it’s got to come back, whatever goes out is going to come back. So that’s sort of where squash and stretch came from.

And it was said that when he came back that there was such a difference in the character that there was great jubilation because they realized now they could do the Dwarfs.

And of course you remember that this lovely Snow White was danced by Marge Champion. She was exquisitely beautiful. She still is at 90. But she would dance on stage and her dress would move and the flowing of the fabric and all of that allowed the artists to see and to understand motion. She would also demonstrate Dopey’s movements – tripping – and she wore a long coat and that sort of thing. And the artists didn’t copy it. They did not copy that. But they used it for reference. Her dance movements, you know, were what they used as inspiration. And so they went back to their studio and it really made the film a lot better watching human motion.

Now don’t ever say to the artists that they used those as in rotoscoping, you know, that they actually…used that film and drew it, because they’ll get quite upset with you, because they didn’t. It was purely reference, inspiration and to understand how fabric moves out, how a big belly moved for instance. You know, in squash and stretch, the belly’s going to come back, you know…and that was important for them – for the artists to understand. What happens when your head moves one direction fast, it’s going to bounce back. You know, so that’s kind of squash and stretch. And so, yes, you’re right, it – using the actors and the singers to perform really had an impact on the film.

RI: As you mentioned it, the Dwarfs bring a lot of humor to the movie. How were all these gags imagined?

LS: They were something that was so much valued by Walt Disney that he would offer a $5 or $10 payment for any gag that was accepted and used in the film. And don’t forget that the artists were living in the depression. You could buy a great dinner for 35 cents, so $5 was a lot of money.

A lot of these artists had come from the world of newspapers. They were pleased to have a job in the depression. And so they were used to drawing cartoons, one scene gags, and they had great fun with these gags. This looks like a scene where they’re brushing their beards or something. I’m not sure what’s happening. But there were just dozens and dozens and dozens of gags presented to Walt for consideration.

RI: Please could you share some of the gags that didn’t make it in the final film?

LS: There were parts of Snow White that were sequences that were pretty fully developed that were eliminated. One of them was a mattress building scene and it was lots and lots of fun. The gags that were developed included Dopey dipping a vine in paint and just wrapping it around a log and the log was painted. And Dopey with a squirrel who was playing the shell game with him and Dopey was losing every time, you know, and tripping over buckets and all kinds of things.

But that scene was deleted. A soup scene was deleted. There was a fight scene that was deleted. And it all came down to the fact that in Walt Disney’s mind they were keeping the story from moving forward. And the most important thing to him was to move the story forward. So they were deleted from the film.

RI: This film has a fairly limited amount of pieces available for research because at that time the idea of preserving artwork wasn’t really present in anyone’s mind. How did you manage to gather all the archival material you have?

LS: The elements of animation that were kept were not as comprehensive in the early days. Walt always kept the animation because he knew that he might reuse it in another cartoon or he might want to go back and look at how a specific turn or something was done. But in the early days the concept art and those sorts of things were not kept.

Now we were very, very fortunate about three years ago to acquire a Snow White collection from a gentleman by the name of Steve Ison. And he had collected over about 35 years. A lot of story gags, a lot of live action reference material. And when he got ready to retire and give up his collection, he thought of us and we were so pleased to get it back because there wasn’t a lot of that early material there.

So, you know, the family members have it, people took it home. He actually bought some of it from artists who had taken it home because there wasn’t the necessity to keep it. As time went on the word got out to people, okay, now, you know, you need to leave this at the studio. But, yes, it has helped our research immensely.

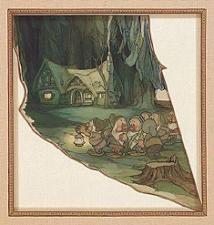

RI: All that material is pervaded by a great European influence. Can you tell us about that?

LS: There was a huge influence. When Walt Disney went to Europe in 1934, he discovered really literature, the art, the architecture. And that influence would continue across – over many years. He reached out to several European artists and asked them to come to the studio, including interestingly enough, I just learned recently, Arthur Rackham, who at this point was retired, and living in the countryside and declined the invitation.

But he really felt that in order for them to give the authenticity to the film that he wanted, he needed someone who knew, for example, German furniture making and architecture. And that is one of the reasons that the film was successful too. There’s an authenticity to the settings that you see of the dwarfs cottage and of the castle, and that was because he had so many Europeans, Herder, and Hovarth, and Tenggren and all of those folks, working at the studio. And that was something that he would continue through for several films. He continued to hire Europeans because they had, you know, the classical European training.

Training was an important part of coming to work at the studio. Walt Disney would bring in a teacher to teach human form or to teach someone to show animal forms so that even the artists who had graduated from schools like Chouinard, well, you know, well trained artists would continue to refine their craft. And he felt that the Europeans brought a lot of that craft to us.

I’ve been fortunate enough to look at a lot of those early books that came back from Europe, now they’re kept in a special locked room but, you know, they were Arthur Rackham and illustrators like that and they’re just exquisite to look at.

And since we’re talking about fairy tales, may I please mention that the ARL has been working diligently for a couple of years on an exhibition that’s opening at the New Orleans Museum of Art on November 15 of this year and will run through March of next year. It’s called Dreams Come True: the Art of the Classic Fairy Tales from the Walt Disney Studio. If you go on the NOMA website you can find out about it.

But our purpose in doing that was to show, you know, how fairy tales have affected the Walt Disney films and we do a big comparison between, you know, the traditional story and the Disney version. And then it’s going to end in art of the making of The Princess and the Frog. And so if any of you get to New Orleans in that time, please see the exhibition.

RI: Speaking of New Orleans and the influence of Snow White on the princesses to follow, how did Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs influence the animators and the creators of The Princess and the Frog?

LS: Well, they always come to the library. They come to the library and look at drawings. Especially story sketches because they like to see how the story process works. They wanted kind of a watercolor feeling of Bambi, of Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs, in this film. The way, you know, the way that Bambi backgrounds are not quite finished, you have as much information as you need. So they come back to the library and they look the art from previous films, you know, to study.

I think also in Princess and the Frog they looked at Lady and the Tramp because, you know, there’s detail in New Orleans architecture that they wanted to have. So they do revisit the older films and look at them, especially the animators.

And we’re really proud of the fact that in Princess and the Frog the directors, John Musker and Ron Clements were able to go to John Lasseter and say, look, you know, we feel that this is a fairy tale, we want it to have a look of the fairy tales, we’re continuing that tradition, let us use traditional animation. And he said fine, yes, go ahead. So we’re real happy about that and the artists were too. Several of the artists came back and were pretty thrilled to be working that way again.

Blu-ray Disc is available to order now from Amazon.com

A million thanks to Lella Smith, Mindy Johnson and Gaëlle Besson!