It is very rare that a follow-up is better than an original. In movies, there are a few sequels, among them The Godfather Part II, The Empire Strikes Back and Toy Story 2, that rate as highly as the films that inspired them did. In the world of publishing, it’s often even rarer. But Russell Schroeder’s Disney’s Lost Chords 2 is one that manages to break tradition and continue a wonderful concept.

It is very rare that a follow-up is better than an original. In movies, there are a few sequels, among them The Godfather Part II, The Empire Strikes Back and Toy Story 2, that rate as highly as the films that inspired them did. In the world of publishing, it’s often even rarer. But Russell Schroeder’s Disney’s Lost Chords 2 is one that manages to break tradition and continue a wonderful concept.

In 2007, with Disney’s Lost Chords, it was the first time an author (and former Disney artist) and historian had researched music’s creative role in Disney’s filmmaking process. Indeed, Russell Schroeder proposed an in-depth book gathering dozens of songs that never made it to the movies, providing a new and intriguing light on the elaboration of Disney’s stories, considering music an intricate part of the process. And to better show how music fully partakes in the creation (story-wise and visually) of the animated film, each of these pieces was accompanied by never-seen-before artwork created at the same time as the song. A treat for the ears and the eyes.

Now, considering the indisputable success of this first opus, and the considerable amount of material existing, Russell couldn’t help but write, edit and self-publish (as he did for the first one) a sequel, Disney’s Lost Chords 2, which proves to be even better than its predecessor.

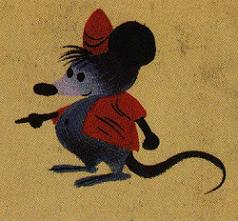

Not only is it fully loaded with new and exquisite artwork, but it offers even more exciting and never-heard before insight about the history of Disney’s greatest films, from Snow White to Hercules. Did you know about all the songs that were composed by Sammy Fain (also an Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan songwriter) and Jack Lawrence for Sleeping Beauty before it was decided to base it on Tchaïkovsky’s music? About the Pink Elephant Polka that preceded Pink Elephants on Parade? Or about the never-released Tale of a Mouse, beautifully illustrated by Mel Shaw during the 70s? And these are just a few examples taken from that gold mine!

With artwork, you could know how a deleted scene would look. Now with the music, you’ll know how a movie was supposed to sound, and feel how the story was supposed to move forward. So, it is with great enthusiasm that we turned to author Russell Schroeder to tell us more about his musical adventure!

Animated Views: Before talking about your books, please, may you tell us about yourself?

Russell Schroeder: I had decided I wanted to be a Disney artist when I was nine years old. This was in 1953, when Peter Pan had its initial release. My family moved from New York to Florida when I was 14. I took art classes all through high school, but in college I majored in Literature.

Since I was still living in Florida when the announcement of Walt Disney World was made, I felt this was an opportunity to work for Disney, in any capacity. I was hired a month before opening in 1971 to work in the boat marinas at the Contemporary and Polynesian Resort hotels. While taking a cash handling class conducted by the merchandise division, I noticed a small art department and asked the manager, Ralph Kent, if I could show him samples of the Disney artwork I had been doing at home so that he could advise me as to whether I should go on to art school for more formal training. Even though I had no professional art experience, I was very fortunate in that he told me he would take me into the department and train me, which he did in may of 1972. Although that art department fell under the merchandise division, it actually provided art services for the entire Walt Disney World property. We also handled jobs from initial design ideas through the finished paintings and mechanicals for printing.

Through the years, my assignments were quite varied. For Merchandise, I designed figurines, posters, T-Shirts and other items that were sold to the guests. One item I designed and painted that sold for many years at both Walt Disney World and Disneyland was a Snow White candy tin. For the Food division, I designed menus and meal boxes, containers used in some of the fast food areas. The food box I designed for Fantasyland was Mickey Mouse’s house. That design later became the basics for Mickey’s House that was built so that guests could actually walk through it and see Mickey’s living quarters. One of the other character illustrators, Don Williams, and I were heavily involved in all the things being designed for that new theme park area called Mickey’s Birthdayland. For the Marketing division, I also produced many illustrations for brochures and posters. My work was always done in the style where the Disney characters appeared, but with added rendering, as they do in the animated films. Special giveaways for Walt Disney World employees (posters, pins, publications) also became part of our work assignments.

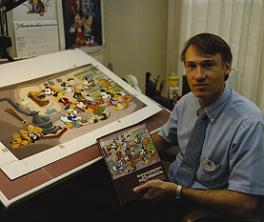

The picture of me I sent you was taken in the mid 1980s while I was working at Walt Disney World and shows a painting I had done for a phone book being used on property. The illustration was evidently very popular, since shortly after it appeared on the phone book, it was used as a collectible pull out in a Disney magazine and then on a large poster that was sold across the U.S. Later a friend traveling in Asia found it on a jigsaw puzzle and picked one up for me!

After 19 years at Walt Disney World, I transferred to the Consumer Products area at the Disney Studio in California, becoming art director for the artists and writers in the Publishing division.

AV: Can you tell me about the different books your wrote before Disney’s Lost Chords?

While in the Publication division, I was asked to write and help put together Walt Disney: His Life in Pictures (incidentally that title is about to be reprinted, at the request of Diane Disney Miller, who graciously had provided the book’s introduction), and Mickey Mouse: His Life in Pictures.

When I went over to Feature Animation to help co-ordinate the book publishing program for each of the new animated features, I was asked to write and pick the art for the “making-of” sections in the collector’s editions of Tarzan and Mulan. After retirement, I was asked to work with the editorial and art director at Dorling Kindersley Publications for Disney: The Ultimate Visual Guide.

AV: How did you get the idea of a book on deleted or never-produced songs?

RS: This book grew out of my love for Disney music and my curiosity about the unused songs I had seen listed in several places. Finding the 100’s of songs I have discovered so far took almost a decade of searching through office files and boxes of material in storage areas both at the Disney Studio and in an off-site warehouse. Other material came from some of the composers themselves, principally Richard M. Sherman and Alan Menken.

RS: This book grew out of my love for Disney music and my curiosity about the unused songs I had seen listed in several places. Finding the 100’s of songs I have discovered so far took almost a decade of searching through office files and boxes of material in storage areas both at the Disney Studio and in an off-site warehouse. Other material came from some of the composers themselves, principally Richard M. Sherman and Alan Menken.

Having copies of the songs’ lead sheets for my own reference, I was spending a lot of time playing them on my piano at home – I had retired in 1999, so had the time to devote to this! I became impressed not only by how enjoyable the songs were in themselves, but by the realization of how vital their creation was in the overall creative process at the Studio. I realized my pleasure would be shared by other Disney fans, and so I set out to see if there was a way to get them published and out for the public to enjoy. I also realized this publication would have to have a proper balance of explanatory text and art, along with the music, to fully appreciate the contact in which they were written.

I did a mock-up of my proposal for this book and submitted it to the Walt Disney Music Company. They approved the idea, but since they release their music through a licensee, it had to be forwarded to them. They felt it was beyond their normal format and turned it down.

After rejections from some of the other publishing areas, I asked the Walt Disney Music Company if they would license me to produce the book, and I would assume all responsibility for getting the book designed, printed and the payment of the royalties for the use of Disney art and the composers’ royalties. They agreed to this proposal. I should add that while I was still an employee at the Studio, I had established a working relationship with the Music Department, and of course, I could not have even started my research without their support and approval. I should also add that the book could never have appeared without the generous help I have received from Ken Shue and his staff in Disney Publishing in obtaining the many images that have added to the beauty of the books.

AV: How did you find all that gorgeous artwork?

RS: Mostly, it was the discovery of the songs that led me to finding if artwork that applied to those songs existed, or had ever been produced. Most of the art I found was located in the excellent storage facilities of Feature Animation’s Research Library. Unfortunately, not every piece of artwork produced at the Studio is still around. So, another source was the Walt Disney Photo Library – which falls under the Disney Archives. Since Disney had its own photography department for decades, many pieces of art were photographed. It was there I found the photos of the storyboards for several Wind in the Willows songs. On the contrary, sometimes, the discovery of particular striking artwork affected my decision as to whether I should include a particular song.

AV: How long did it take you to finish each volume of Disney’s Lost Chords?

RS: I started engraving and making the music arrangements over a period of about seven years. This was started before I knew there would ever be a book. I was making the arrangements for my own pleasure. The lead sheets I was working from were in various stages of completion and legibility, which precluded them being reproduced for printing. Some composers wrote out a full vocal and piano arrangement. Some just wrote the vocal line with chord symbols. And some, such as the Charles Wolcoott songs for Cinderella, just had the vocal line, with no chord symbol or accompaniment indicated. Help in creating the full arrangements came from listening to some of the demo recordings that still exist for these songs. I also received some help from several musicians with pieces that I found particularly challenging, given my limited musical skills. Among those songs, The Wuller-The-Wust lead sheet only contained a vocal line, no chord symbols, but I had the demo recording to help me.

Song of the South‘s I Ain’t Nobody’s Fool was not located as a lead sheet, so that arrangement was made solely from the demo. I tried always to identify in my books those songs that were based on demo recordings. And, since much of the material used in the second book originally had been gathered and planned for the first volume, the second volume was produced in about a year and a half.

RS: The Walt Disney Music Library, headed by Booker White, gave me full access to their files and storage areas. Since they are usually a beehive of activity in preparing the scores for the various new films for their recording sessions, they did not have time to assist in the actual search process. At the Animation Research Library, I principally worked with Ann Hansen, who, prior to my visit, would receive a lengthy list from me as to the material I was hoping to find. She would then pull the archival storage boxes that seemed appropriate for me to peruse. Other staff members, of course, also helped me when they heard I was looking for something, and they had knowledge of its existence.

The Walt Disney Archives was a primary source for story conferences, memos and other ephemera that helped enlighten the material I was dealing with. Mostly every song in the two books is appearing in print for the first time. Two exceptions are Proud of Your Boy and Shooting Star. These appeared in The Alan Menken Songbook, but they were not identified as to film source. So, I felt justified in including them in my book, since I was putting them in context with their creation. Besides, I thing Proud of Your Boy is a particularly moving and beautiful song and I felt it deserved this showcase.

AV: Can you tell me about the composers you met along the process?

RS: Unfortunately most of the composers had passed away by the time I got into this project. And while I was still working at Disney there were only a couple of composers I had contact with. One was Buddy Baker, who had been set up in our Walt Disney World art department for a few days when he came to Florida in preparation for the opening of EPCOT. Since this preceded my work on the lost songs, I didn’t avail myself of the opportunity for an in-depth interview. I had met Richard Sherman at a few Studio functions and in at least one social situation – also before this project was underway. And had attended several of his entertaining presentations, in which he talked about working with Walt and played and sang the Shermans’ familiar songs from the film scores, as well as a few deleted numbers.

RS: Unfortunately most of the composers had passed away by the time I got into this project. And while I was still working at Disney there were only a couple of composers I had contact with. One was Buddy Baker, who had been set up in our Walt Disney World art department for a few days when he came to Florida in preparation for the opening of EPCOT. Since this preceded my work on the lost songs, I didn’t avail myself of the opportunity for an in-depth interview. I had met Richard Sherman at a few Studio functions and in at least one social situation – also before this project was underway. And had attended several of his entertaining presentations, in which he talked about working with Walt and played and sang the Shermans’ familiar songs from the film scores, as well as a few deleted numbers.

Once I began this project, and I was living on the east coast, I contacted Richard Sherman [right] by phone. He was very forthcoming about answering my questions and even sent me quite a few lead sheets that I hadn’t been able to locate at the Studio. I also sent him several of the arrangements I made from his lead sheets for his approval before publishing. Mel Leven and Carol Connors were other composers with whom I conducted phone interviews. My contacts with Alan Menken [right, above]and Stephen Schwartz were through their assistants. I requested several lead sheets that had eluded me in the Studio’s files, and both composers agreed to have copies forwarded to me.

AV: What is the discovery you’re the most proud of, and why?

RS: That’s difficult to narrow down. There are so many that I was pleased to be able to make Disney fans aware of. Horse-Sense from Cinderella, since it illustrates an original approach to the characters that was later abandoned. I only located the original Sammy Fain/Jack Lawrence songs for Sleeping Beauty in 2007, so being able to include them in Volume 2 was particularly satisfying.

Although the song wasn’t able to be included in the books because of space, one intriguing discovery was written for Alice in Wonderland – The Lobster Quadrille, set to Lewis Carroll’s lyrics by Frank Churchill in 1939. In an interlude section there’s a melody passage that evolved into the Never Smile at a Crocodile theme in Peter Pan. I have made several presentations on the lost songs with the help of a pianist and some singers. At one presentation we played this passage, giving the audience a chance to make this discovery themselves and call out the music when they recognized it.

AV: I found the Tale of a Mouse project very interesting, with splendid artwork by Mel Shaw. How did you come about that one?

AV: I found the Tale of a Mouse project very interesting, with splendid artwork by Mel Shaw. How did you come about that one?

RS: I had first seen the project and songs listed in a catalog produced by the Walt Disney Music Company in the late 1970s. While looking through lead sheets in the Music Library I recognized these pieces, since the song titles were already familiar to me. I then found photostats of the original storyboards, as well as the original Shaw pastels in the Animation Research Library. However, I couldn’t find anyone at Disney who remembered the project. I even contacted one of the retirees who had been in charge of animation, but no one could enlighten me. Then I obtained Harry Tytle’s autobiography One of Walt’s Boys, and he gave some background on the project, since he had been instrumental in developing it. It was after that that I was also able to contact Mel Shaw and he provided further information. I think people who read music will be particularly impressed with this original score.

AV: Can you tell me about the writing of the music on old lyrics from Peter Pan by Richard Sherman?

RS: When the people at Walt Disney Home Entertainment begin preparing for a new DVD (now Blu-Ray also) release, one of their first stops is the Walt Disney Archives, where they go through the file boxes looking for things that they might include as bonus material. One of the things they look for is mention of early songs that were eventually not used. One of the files contained these lyrics, but no composers were credited and further search did not reveal a lead sheet or demo. So they asked Richard Sherman what he thought about the lyrics and whether he would like to set them to music. He readily agreed, and just had to make a few changes to the lyrics so they worked better with his original music.

AV: What would you keep from this adventure on Disney’s Lost Chords 2.

RS: Just that I appreciate the cooperation of the many departments at Disney whose doors were always open for my research and who shared my enthusiasm for the project. And I also appreciate that the Walt Disney Music Company had faith in me, a first-time publisher, to produce a volume that would do justice to their composers and their creativity. I’m also pleased that so many Disney fans, who were the people I did this for, have embraced the project and thanked me for doing it.

AV: Is there anything you would regret?

RS: Not having room for some of the pieces I wanted – and still would like – to include. Learning how to do layouts and mechanicals on the computer, since when I was an artist on the drawing board, all our mechanicals were done by pasting type and line art in place, cutting overlays for limited color, and using position stats.

AV: It sounds as if there could be a third opus?

RS: There is a lot more material out there, both songs I have found and others I would still like to locate. Some of these I have already arranged and chosen art for, but at this time a third volume is not being planned.

Our gratitude goes to Russell and Laura. Extra special thanks to Didier Ghez and Antoine Clarisse.