Do you know what a “Neo-Soundie” is? To tell you the truth, neither did I before talking with short animated movie You’re Outa Here creators Lorraine Feather and George Griffin! As director and animator Griffin said it: “As the song is so clearly jazz and references an earlier period in our culture when jazz was the popular idiom and short documentary films of great artists like Waller were called soundies, it seems appropriate to call You’re Outa Here a ‘Neo-Soundie’.”

Because this brand-new short is all about jazz! Just consider its creators:

Lorraine Feather was born in Manhattan. Her parents named her Billie Jane Lee Lorraine after godmother Billie Holiday, her mother Jane (formerly a big band singer), her mother’s ex-roommate Peggy Lee, and the song Sweet Lorraine. She is the daughter of the late jazz writer Leonard Feather. Now a noted jazz singer and songwriter, her credits associate both discographic successes like New York City Drag, Cafe Society and more recently Language, along with cinematographic and television participation in ABC’s Dinosaurs, Touchstone’s Dick Tracy, MGM’s All Dogs Go To Heaven and Disney’s Jungle Book 2.

As for George Griffin, he’s a well-known jazz devotee. A New-Yorker since 1967, he apprenticed in commercial cartoon studios, was influenced by Robert Breer and Saul Steinberg, and made his first animation with improvised equipment in 1969. His work includes self-referential cartoons, narratives, documentaries and experiments with music like Head Viewmaster, Ko-Ko and A Little Routine. His offbeat sensibility was the perfect match for Lorraine’s as they were working together on You’re Outa Here throughout 2008 and made it this story of a feisty descendant of Betty Boop who has finally had enough and kicks out her clueless boyfriend while delivering a taunting, full-throated indictment, to the barrelhouse rhythm of Fats Waller!

Very Fleischer-esque indeed!

Lorraine Feather, Such A Sweet Songwriter

Animated Views: First of all, how did you get the idea of writing lyrics to Fats Waller’s Minor Drag?

Animated Views: First of all, how did you get the idea of writing lyrics to Fats Waller’s Minor Drag?

Lorraine Feather: What happened was that in 1999, for some reason, I became infatuated with the music of Fats Waller, which I hadn’t heard as much growing up as I heard a lot of bop composers. As a lyricist, I had been doing some stuff with MGM Animation; they had just closed their doors and I was looking for something interesting to do. So, I decided to write lyrics to one of these Fats Waller pieces. It was called Smashing Thirds. I didn’t know anyone who could actually play the music, so I took the original recording, which was solo piano, and went into the studio with a bass player and a drummer, and I recorded the vocals over that. I sent it to Dick Hyman, the great stride pianist, whom I had known through my family, but didn’t know well on a one to one basis. He called me up and said: “if you do a whole album of Fats Waller pieces with lyrics like this, I’ll play on it. I’ll help you figure out which ones to record.”

So, I did and, in the midst of doing this album, I got together with Dick to work on some of the tunes I had written so far. We rehearsed at David Abell’s Pianos in Hollywood. Dick said: “have you ever heard this one?” and he started playing The Minor Drag. I thought it was the most fantastic Fats Waller piece I had ever heard in my life. I loved it so much. I eventually wrote lyrics to it and it became my favorite tune on the album. So, I used it to open the CD, which was called New York City Drag. It came out on a small label, Rhombus Records in 2001.

AV: What was your inspiration for those lyrics? How did you go from an instrumental piece like The Minor Drag to the story of this couple splitting up?

LF: I think it was just the intense energy of the tune that led me to the idea of somebody yelling at somebody else, like: “Get outa here!” I almost don’t remember writing the song. I thought of the title, the hook, and then the rest of the song, as it often happens, evolved around this. Musically, also, a lot of what I’m singing, the melody, did not exist in the original. It’s a just a variation of what was originally there.

AV: Your albums are often accompanied by shorts you shoot yourself. Can you tell me about your taste for pictures, in addition to music?

LF: I’ve never done it consciously but people have said to me over and over that my lyrics, my songs were like little films. It’s just the way I naturally write. It’s not a very “pop” way of songwriting.

AV: That explains the fact that you wrote a lot for cinema and television, like Jungle Book 2.

LF: Yes. The first work of that kind I did was the TV show called Dinosaurs, with composer Ray Colcord, whom I’ve known for some years. That was about a family of dinosaurs, a pretty sarcastic show produced by Disney and ABC. There were blues songs sung by the dinosaurs, and country songs. And then eventually I did other projects of that nature with Mark Watters. It doesn’t feel that different writing songs for kids’ animation and writing adult songs, for some reason.

AV: Now, how did you get from writing lyrics for an instrumental piece to producing an animated short on it?

LF: I was performing some of my Fats Waller tunes at a club in LA a few years ago with the pianist Shelly Berg. After the show, Nancy Knutsen, the head of the film department at ASCAP, said: “You should make an animated short out of that song.” She was talking about another song called Alligator, based on Valentine Stomp. I had it in my head for years but didn’t know how I would go about it. I was discussing the idea with some friends of mine, one of whom knew Frank Mouris, who, with his wife Caroline, won an Oscar for an animated short called Frank Film and suggested I contact him. So, I wrote to Frank, who was in the midst of doing a project with his wife.

I sent him some of my music and he emailed me recommending a few animators he thought might be interested in working on such a thing. And the one that I connected with right away was George Griffin. I sent him all of my music, everything I had done up to that point and he said: “if I’m going to make an animated film, the song that really does it for me is You’re Outa Here.” He loved the energy of it and could see it as an animated short. So, we tossed around some ideas and then, in 2008, he did it!

AV: How did you work on You’re Outa Here as a producer?

LF: George sent me images and asked my opinion about certain things and, of course, sent a storyboard, and I gave my feedback. But, creatively, I didn’t tell him what to do very much except that I didn’t want it to be a music video, no live singing. He brought up the idea of using Dick Hyman at the start, like an old Max Fleischer cartoon. He suggested having Dick Hyman in black and white at the beginning, and I thought that was a fantastic idea. And now, we’re working on the presentation of our short in different film festivals.

AV: From an instrumental piece to a song and then to an animated short, what an impressive transformation!

LF: Thanks! I love this particular piece, the original music, so much, and this is just a way of, I hope, having people enjoy it on another level. And George really understood the song. He came to see me perform in New York and he made the female character a bit of a caricature of me. Our sensibilities went together very well. I like the way he has the fish in the fish bowl turn into a piranha waiting to bite, the way he has the dog like a little toy dog on a platform. It’s very whimsical; nothing I would have thought of. So, George made it into something else that I love.

AV: Watching the superposition of live footage of the pianist’s hand and animation, I thought, as you mentioned it, about Max Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell, but the transformation, in the bridge, of these hands into animation also made me think about the beginning of Fantasia, with the orchestra becoming drawings and lines.

LF: Yes, there is a little bit of Fantasia. My dream is to do the lyrics for a full-length movie that could be like a jazz Fantasia. It’s funny that you say that, because I’ve never mentioned it to George.

AV: What can we wish You’re Outa Here for the future?

LF: I’m hoping that it’ll play at many more festivals and go as far as it can go, and lead to something else!

George Griffin, The Viewmaster

Animated Views: Why did you accept to take part in that project of animating on a jazz song?

Animated Views: Why did you accept to take part in that project of animating on a jazz song?

George Griffin: I love jazz. Like animated cartoons, it’s America’s cultural gift to the world. Its rhythm flows in our traffic patterns and poetry. It’s spontaneous, parodic, sarcastic, sassy and in-your-face. This particular song has a pre-modern melody based on the happy, propulsive swing of the two-fisted stride piano; it’s very danceable, like all jazz in the 1930s. Then, the lyrics are a riot. They supply a countervailing element that sounds almost post-modern: dripping with irony, chockablock with hip, contemporary references, yet also universally funny.

When I first heard it I retained about a quarter of the meaning. It was so fast and so clever that my first reaction was, “Did she really say that?” Her voice enunciated every syllable perfectly and the personality that came through was so self-possessed that a character just seemed to jump out of the song into the frame. She’s not whimpering about the love affair ending, she’s kicking the dude out; she’s really in control but there are little patches of tenderness and bitterness that make her also quite human.

AV: What first came to your mind: the story or the visual? How’s that?

GG: I’ve done a lot of independent films which I would define as films made primarily for yourself: no market research, product, script or concept vetted by focus groups; just whatever tumbles out of your own head and heart. And I’ve always started with a title, words that can guide me when the design gets a little messy.

I’ve also done a lot of advertising and industrial production and worked in collaborative studios. So this project was a bit like taking the best of both worlds. Lorraine had written and sung the words; the title was set. And she in effect gave me carte blanche to illustrate the song. That meant interpretation, design, choreography would be my responsibility, but with her tacit approval. We just seemed to easily agree on every major decision that arose.

The other “I” word here is illustration. It can become tedious and didactic, or decorative, too literal. Illustrators, to their chagrin, are rarely allowed into the highest strata of the art world because they are too popular and tend to be burdened with the message of their patron. But my mission was to serve the lyrics of YOH.

The first image I came up with was Betty Boop striding toward the viewer with a bone to pick. I’m not sure I can say why. Lorraine’s voice has none of the nasal squeak of Mae Questal. Maybe the character of her clueless ex-boyfriend suggested the cast of ineffectual male characters surrounding Betty. She’s sexy and she’s on the warpath.

AV: How did you build your story?

GG: Each line had one or two gags just screaming out for recognition and I talked over some with my friend animator Debra Solomon who spun off quite a few more ideas which I sketched out and wrote down. I also spent a lot of time procrastinating: re-arranging furniture, finishing up producing some documentaries on artists, having heart procedures—all pretty boring.

First came the character design and sketching some scenes to figure out where they act. As so often happens, I’d plan out something very elaborate and then edit down to the essentials. I actually edited the live action sequences while still doing the storyboard, which was done on paper over the course of about a month. I occasionally layout and animate some stuff as I’m boarding.

My assistant, Gretta Johnson, did the rotoscoping of the dancers I had downloaded from YouTube. She followed my general character ideas but improvised freely in Flash, before I composited in After Effects. This rather complex technical stuff just arrived fully formed while I was struggling with the details of narrative structure in the sketchy board.

AV: Is your point of view feminine or feminist?

GG: Those are loaded terms. Maybe you should explain…haha! I’d have to say neither. First, if you let your POV run your art you have failed to deal imaginatively with the characters and ideas you have conjured up; you’ve got to be free, or your just doing propaganda. Of course many animators from my generation (who were women) brought something to the table that hadn’t been there before, like sensitivity to human relationships, sex, love, anger, and the foregrounding of direct, manual craft. But I find essentialism an unhelpful framework. Artists tend to be pretty AC/DC and infantile to boot.

AV: About the main female character. How did you create her?

GG: First there is the leopard fur mini-skirt: just something I always wanted to do and which is now so easy in Photoshop (and it really is furry in HD). She has those prim Tina Fey glasses which can be tilted to telegraph various emotional states; they make her “smart” and a little scary, but they also are sexy because they suggest something forbidden, yet hidden in plain sight. Her “feminine” proportions are just about as extreme as Betty: big head, big lips, big hair, “cute figure.” In her fuscia pumps she suggests a high school English teacher who might moonlight as a pole-dancer.

AV: How much is that character Lorraine, and how much is it not?

GG: Of course I’d seen photos of Lorraine before I met her in person (and she saw some of my films that feature photographic self-portraits and a line drawing square man character). And the idea of a caricature of Lorraine was always just below the surface of our discussions. Up front she said she liked the square man as the cartoon guy. I don’t think there were any direct appropriations of her personality or environment. Little things like mannerisms can seep in from so many sources: people we knew in childhood, cartoons we’ve seen, people we love. She had a dog but I don’t recall a fish or a cat. The Kit Kat clock is invented but she told me later that she and a former boyfriend used to have one.

I never asked her if the lyrics were based on her life, as in “who was this guy you dumped?” That would have been too personal and might have limited my own ability to imagine it. For example the apartment is rather dreary; I really can’t imagine Lorraine living there.

AV: What did your meeting with Lorraine in New York change in your perception of the song and your visual interpretation?

GG: Last winter, I saw Lorraine perform YOH during a gig at the Oak Room in the Algonquin Hotel, a classic venue with a great trio accompaniment. Her performance and the whole milieu served to reinforce the tradition of stylish linguistic repartee: Noel Coward as filtered through Harold Pinter. She doesn’t just vocalize the iconic melodies of jazz, she breathes fresh life into them while inventing new forms.

At that point I had just made a few sketches which she liked (she said she was “stoked”). That’s all I needed to hear.

AV: How did you create the male character?

GG: I recently finished a cartoon called It Pains Me to Say This which contained two version of “my” square man, first as an extremely minimal diagram, then developing into a more nuanced guy with a nose and hair. The YOH version is somewhere in-between with Bart Simpson hair. He is basically just a foil for her put-downs/send-offs, mutely reacting or acting out vignettes of his past behavior, as if to demonstrate his unconsciously creepy tendencies.

She dominates the narrative space, consumes all the oxygen and monopolizes the moral high ground, so the trick was to allow him a bit of sympathy. During the first rotoscope sequence we see an abstract couple dancing in harmony; we can imagine that it’s a brief memento of an earlier, happier time. And by the song’s end he seems both chastened and perhaps a bit wiser.

AV: Can you tell me about the visual style, the art direction you conceived for the film?

GG: Not much to tell except it’s probably more consistent and cartoony than my other stuff. But it stops short of aping the look of vintage Fleischer.

AV: What were the artistic and technical challenges of that film?

GG: I actually forget how to do a lot of things and have to re-invent certain practices for each film. This can be inefficient but sometimes leads to new solutions. My brilliant students at Parsons also pointed out some dandy shortcuts, like layer sequencing.

AV: What kind of animation techniques did you appeal to?

GG: I used very basic sequence drawing (pen on paper) with coloring in Photoshop, comping and keyframe dynamics in After Effects, final editing in Final Cut Pro. I often simplified and limited characters’ movements so they would “read” better. The overall structure of the action relies more on setting up and cutting through about 60 scenes than on animation for its own sake. In that sense I was more indebted to UPA than Warner’s.

AV: Can you tell me about the importance of Max Fleischer in your work on that film?

GG: First there’s Betty Boop; then, the use of rotoscoping, which Fleischer actually patented, and the combining of cartoons over live action; but mainly it’s the rhythmic bounce of jazz which one associates with the Fleischers.

AV: How did you build the pace of the film?

GG: The pace was already set by the pre-recorded up-tempo music. The film begins and ends with live-action hands playing the accompanying piano melody, a note for note rendition of Fats Waller’s Minor Drag. This is the legendary virtuoso Dick Hyman; he makes it look fun, which is a large part of the pleasure of Fats Waller. And the sync was easy because Dick accompanied Lorraine on the CD.

We videotaped Dick at Nola Studio where Charlie Parker recorded Ko-Ko in 1945. This BeBop anthem was the basis for my other jazz film which was created with abstract bits of torn magazine pages.

AV: How did you get that idea of beginning the movie with some live footage of the hands of the pianist? Why?

GG: I’ve always been interested in the contrast between documentary cinema (real time and space) and the imaginary, synthetic world of animation. It’s a contradiction that drives my work, just as it did for my heroes Cohl, Fleischer and Breer.

AV: The film is somehow sarcastic. What did you want to express through it?

GG: Hmmm…trick question? It’s not a pretty picture, or a sweet ending of reconciliation; the couple is splitsville. But rather than say it’s a sarcastic film, I’d say it’s an honest cartoon portrayal of a woman who is mad as hell, but also snarky/funny, using weaponized language for self-defense.

AV: What will you keep from that experience?

GG: It was great to work with such a wonderful writer as Lorraine. The drawings of the storyboard grow directly out of the lyrics so it’s accurate to say we are co-authors. I wouldn’t change a thing.

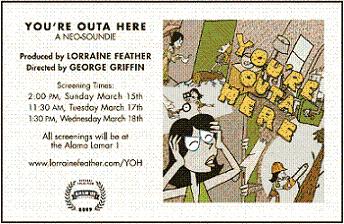

South by Southwest 2009 Film Festival:

You’re Outa Here is also playing at The Underground Film Festival in New York, the Boston International Film Festival and at the South Beach Int’l Animation Film Festival.

With very special thanks to Lorraine Feather and George Griffin.