As an introduction to our LaserDisc Archives series, we thought it might be fun to take a trip on the way back machine and travel down memory lane to revisit the original shiny disc movie format, discover some background history, see how LD inspired the future of Compact and Digital Versatile Discs, and reveal that there’s still life in the old discs yet…

Way back when Warner Home Entertainment’s animated feature Cats Don’t Dance was finally issued on DVD, we were all expecting a nice new transfer of the film in its original aspect ratio. But, as we had seen from Warners’ past fiasco with the live-action Willy Wonka disc, and the later Powerpuff Girls Movie, the company seemed to be against releasing kids and family orientated programming in anything other than full-frame 4×3, be it open matte or pan-and-scan. Well that got us to thinking about the good old days, when shiny movie discs were 12-inches wide, and almost all programming was available as the director intended. In the LaserDisc Archives, we’ll be taking a look at some animated titles that are actually better represented on the original LaserDisc format, from films already available on DVD, to some that we have yet to see make an appearance in the digital realm. But first, and for those wondering what a “LaserDisc” actually is, a little history…

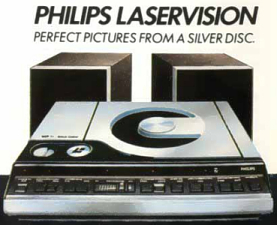

First introduced to the public as early as the mid-1970s, LaserVision, as it was then called (see picture below), was promoted as a high-resolution movie carrying device that would present the home viewing experience on a new level. Competing with Beta, VHS and several variables of videodisc and tape formats (CED, V2000 and my favorite name, DiscoVision) there was a format war. Due to JVC licensing their VHS technology to outside companies, Sony’s Betamax died out pretty soon, leaving VHS as the tape-based victor, due to its ability to record television off air (something LaserDisc would never be able to do in the home). Phillips and a selection of other manufacturing companies stripped the 44.1/16 bit stereo PCM audio tracks from the movie videodisc format and applied it to a smaller, compact version of the disc. That was the birth of the CD.

As Compact Disc gained in popularity, and pre-recorded home video titles became available to purchase, the videodisc format was pushed again, this time as LaserDisc, with the big selling point that the format carried “CD quality sound”! In America, early-adopter movie collector enthusiasts welcomed the high-end format with open arms. At first, much of the programming was only available in full screen, until Woody Allen insisted that the wonderful widescreen photography he had shot for Manhattan should be reproduced on the LaserDisc in the same way. The term “letterbox” was coined when someone complained that watching the picture on a standard TV screen was like watching it through a letterbox! Still a problem to this day, people often think that they are actually missing picture in a letterboxed presentation, rather than realizing that they are seeing the intended ratio, with extra picture information either side. Of course, laser fans picked up on this pretty quickly and soon there was quite a demand for widescreen releases. The Voyager Company started their Criterion label, which took library releases that the studios did not know how to market, and produced lavish LaserDisc box set versions, often with bonus materials such as commentaries, trailers and featurettes that were format exclusives.

Steadily, LD took off as the home video format of choice, and with the rise of more affordable (but still expensive!) video projectors, the higher-than-VHS-resolution discs allowed themselves to be blown up for large screen viewing. Although a success in the United States, Japan was the only other country that embraced the LD format from the get go. In other countries the discs were re-branded several times in an attempt to make people “see the difference”, as one advertisement put it. Other names for the format included CDVideo and VideoCD, a name that would soon be associated with a true CD sized video disc. Referred to in marketing as CD-I, these Compact Disc-sized movies were the first attempt at what would become DVD. Containing 74-minutes of video per disc, it meant that most films would be spread over two or more sides. For LD fans, this wasn’t a problem: we had been doing that all along. What was a problem for everyone was the quality. MPEG-1, at that stage, did not have the tools to cover up bad compression, or process the video cleanly enough. The first discs, supported by studios such as Paramount, did not sell well at all, and the product was pretty much DOA. However, it did get the technical bods to thinking about the next level of MPEG…

The compression on a DVD is created in the MPEG-2 standard, with Dolby Digital selected by the format committee as the primary audio carrier. Dolby had been at the forefront of cinema sound technology for years, creating the first two-track surround tracks, and the leader in 5.1 theater audio. Their collaborations with LucasFilm’s THX brought about a revolution in home audio reproduction, kicking off the home cinema concept in big style. And it all started with LD!

LaserDisc is not an all-digital format, as some might believe. The audio portion is made up of two sets of stereo pairs. The digital pair carry left and right audio, as well as matrixed-surround information (Dolby 4.0). Then there is another, analog pair which can carry either a copy of the digital tracks for older analog players, or additional audio. As the studios began to play with these ideas, we saw multi-audio logos on some discs that offered the movie’s audio in digital, and the music score on the analog tracks. Sometimes, this would be supplemented by a director’s commentary – just like we have now on DVD. With the coming of Dolby Digital 5.1, or AC-3 (Audio Coding v.3) as it was known back then, disc tracks were split into a variety of ways. Often the digital tracks would carry the Dolby Surround movie, while analog 1 (left track) had a score or commentary. The analog right, on track two, would carry the uncompressed Dolby Digital stream, with the 5.1 sound information decoded when it reached the amplifier – the exact same audio process through which we now enjoy on our DVD audio. Picture-wise, the format was still analog, but as the laser only read the disc and did not touch it, there was little chance of degrading.

As with comparing vinyl records with CDs (where music enthusiasts swear that the vinyl sounds “warmer”), many LD fans still have the feeling that LD has a more filmic image than DVD. Where as DVD is compressed to allow hours of audio and video onto the discs, LD is uncompressed, meaning that one frame of film means one frame on an LD. Totally uncompressed, and running at standard speed (named CAV – Constant Angular Velocity), an LD would only hold up to 30 minutes of material per side, meaning changing the disc a few times for an extra long movie. Although later players featured a self-side change mechanism, the original way around that barrier was CLV (Constant Linear Velocity), or basically “long play”. These discs would hold up to 60 minutes per side, allowing most films under two hours to sit on one disc. The added speed in rotating this longer discs, however, did not allow freeze framing, or slow motion replay, so many effects films and animated titles would have two issues: the CLV movie only, and CAV special editions. Even now, I would have to agree that an uncompressed CAV disc could still outshine a DVD pressing. Third in line would be CLV, as the image would not be as sharp as either a CAV or DVD. This would be dependant on the company and where the disc was mastered (a whole topic for LD fans in itself!), but even some CLV discs can rival a DVD any day (my Men In Black laser is indistinguishable from the Limited Edition DVD).

Most importantly though, when it came to animation, laser fans were well served, and many of DVD’s initial issues were merely ports over from the original laser version. Image Entertainment offered many old-time animated shorts and rare features, and Disney’s remastered LaserDisc collections were very handsome, often coming in huge box sets with many hours of bonus materials. Some of the bigger sets also included hardcover books, additional CD soundtracks and lithographs! We even had menus of a sort on LD, even if they weren’t as interactive. Chapter indexing was also another LD concept brought over to DVD. In all, it was a fantastic format, and even though disc pressing decreased as the new DVD format came in around 1997/98, and players have become harder and harder to find, the LD format has not died out completely. Movie fans dying to watch the original versions of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones trilogies in official, widescreen and digital sound versions are plugging up eBay with requests for players and discs. Animation fans, too, are finding that they may be missing out, especially with some of the recent releases on DVD, which don’t always carry over some of the “secondary” content (The Lion King, Alice In Wonderland and The Hunchback Of Notre Dame all contain much more on their laser incarnations).

Which brings us back to the intended focus of this series – namely, when LaserDiscs outshine their DVD counterparts! It is wrong to assume that a DVD is automatically better quality over an LD, and likewise with LDs. Both have their strengths and weaknesses, apart from their obvious size differences (although there are combi-players available which will play any form of optical videodisc, as seen above). Whereas a DVD can suffer from artefacting and pixelation, an LD can have drop-outs and does not handle deep reds amazingly well. Most DVDs will come with anamorphically enhanced widescreen transfers, leaving LD with straight letterboxed versions. But wouldn’t you prefer a letterboxed version of a movie rather than and pan-and-scan edition, given the choice of whatever the format?

So, there you have it. While the LD format has wavered in popularity over the years, laser fans still have reason to keep their copies of various movies, simply because they are available on LD in their original aspect ratios. Of course, when high-definition discs become more widespread, we’re all back to square one, with no more talk of LD collectors “cross-grading” to DVD. Everyone will be upgrading to the new format, LD and DVD owners alike, and probably grumbling about it as well, no doubt! But you know what? Even then they’ll be some titles that elude both the DVD and HD-DVD formats, and there us laser fans will be in the corner, clutching our old 12-inch discs!