Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1963-1967), CLV box set with extensive booklet liner notes, 3 discs/6 sides, 34 complete cartoon shorts produced or directed by Chuck Jones, 5 hours, 1.33:1 original full-frame ratio, Digital Sound, Not Rated/Rated G

With the majority of the cat ‘n’ mouse’s oeuvre still to debut on DVD, what better time is there than now to take a look back almost 15 years (!) to when animation historian Jerry Beck co-produced a trilogy of fine LaserDisc box sets starring the bickering duo.

MGM/UA Home Video’s early 1990s collectors anthologies were grand affairs, counting among them sets devoted to the Happy Harmonies, Tex Avery, The Golden Age Of Looney Tunes and, of course, the celebrated team of Thomas, the cat, and his nemesis Jerry, the mouse. These collections, under the banner of The Art Of Tom And Jerry, brought together all of their motion picture appearances, including original CinemaScope shorts and sequences from other feature films, save their short lived (and best forgotten) European series and the 1990s update movie.

THE ART OF TOM AND JERRY: VOLUME THREE rounds off this series, with a collection of the later Chuck Jones-produced films, in another three CLV disc set. With MGM having shut down their animation department and thinking that older, catalog shorts could generate just as much revenue as new cartoons, they soon found that there was still much demand for freshly created films from theater exhibitors, who balked at paying good money for the same old product twice. Now that Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera had left to begin their prolific television output, the Studio decided a cheap way of continuing the cartoons without the need to actually run a cartoon unit was to lease the characters to Czech animator/director Gene Deitch, who created a short-lived series of such lacklustre shorts that they were all but disowned by the company.

Around this time, and with the closure of the Warner Brothers cartoon outfit, Chuck Jones had set himself up in business as Tower 12 Productions, and MGM tapped the director with the proposition of redesigning their famous cat and mouse duo for a re-vamped series. Jones accepted the not so easy task and re-defined their personalities in a Road Runner/Coyote-type light, and their characteristic visual appearance also changed a little to reflect the wry look Jones fans will recognise from such characters as Wile E Coyote and Pepe Le Pew. The cartoons were only moderately successful, but did the job of keeping Tom and Jerry in the public eye, even if nowadays this series is very rarely seen. That’s a shame, as some of these cartoons contain really good gags and develop the characters beyond the simple chase genre that gave the H-B cartoons their spark.

Here Tom and Jerry are more mischievous, with careful plotting taking the place of a quick and painful revenge. Certainly, these cartoons are of their time, the mid-1960s, but within that range there were also some new things brought to the shorts, such as the idea of spoofing popular trends and other films, which was a popular movie concept at the time when the comic Cat Balloo aped epic westerns and In Like Flint was the Austin Powers of its day, turning the James Bond phenomenon on its head. Jones was always at the forefront of animated parody, and kept this up through this series.

As this set kicks off, with Pent-House Mouse (1963), one notices that one remaining element that has not changed in the Jones shorts is Scott Bradley’s unmistakable theme (though actual scoring duties would be taken over by Eugene Poddany). Over the years this theme has accompanied Tom And Jerry’s many title card picture switches (the biggest swap came with the jump to CinemaScope) and here they now have an entire animated sequence that opens each film, with Tom replacing Leo, the celebrated lion in the MGM logo, sniffing and growling as best he can, while Jerry floats down and plumps himself cosily on top of his name, sliding into the final letter like it was a cocktail glass. It’s a great opening and firmly sets this series up as something new.

Though previous cartoons in the T&J series had been made in widescreen CinemaScope, the Deitch cartoons (none of which are presented in any of these Art Of sets) resorted to the full-frame 1.33:1 ratio. Jones’ cartoons fall somewhere in-between, coming at a time when the majority of films were photographed to a full-frame negative and then matted to a 1.85:1 ratio in theaters. Most of these cartoons are visibly framed so as not to lose any vital picture information if cropped, but thankfully, and quite rightly, this set presents the films with the full negative exposed, so as to see the entire image.

Jones kept many of his Warner Brothers associates on with him at Tower 12, including storyman Michael Maltese, designer/co-director Maurice Noble, animator Ken Harris, director Abe Levitow and voice artists June Foray and, of course, Mel Blanc (although T&J still rarely speak in these films). Pent-House Mouse looks and feels like a 1950s Warner Bros cartoon, in particular One Froggy Evening. We find Tom lazing about in his stylish top-floor apartment, acting very suave in typical Chuck Jones fashion. Poor Jerry on the other hand, is desperate for food, so when he spots a workman’s lunch on a nearby construction site, he tucks in. Unknown to Jerry, the lunch pack gets towed up on a beam destined for the top of the high rise, but it falls off, landing on Tom’s head. And so begins the battle between Jones’ take on Tom and Jerry…

With 1964’s The Cat Above And The Mouse Below, Jones invokes his taste for classical music when “Thomasino CattiCazzaza” attempts to sing the Rigoletto to a packed house, not realising that Jerry is trying to sleep beneath the stage (the cartoon also recalls the earlier 1949 WB short Long Haired Hare). Is There A Doctor In The Mouse? features some great gags when Jerry concocts a potion that gives him super fast speed and Tom tries to catch him on film – the “slow-mo” replay with the action all mapped out is a very funny touch. A Spike replacement (looking very much like a certain canine from the WB films) appears in Much Ado About Mousing, Jones’ first beach-set short, in which Jerry is protected from Tom’s fishing by the dog, who gives him a whistle to blow if he gets into trouble – a very similar set up to the earlier Fit To Be Tied.

Snowbody Loves Me (which has the most random “what the?” ending to any T&J cartoon) also returns to the basic H-B formula: stuck outside in the cold, Jerry tries every trick in the book to get in and munch on the Swiss cheese that Tom has inside, while The Unshrinkable Jerry Mouse has Jerry protecting a little kitten from Tom. It’s cartoons like these that reinforce the view that the more things change, the more they stay the same, and although Poddany’s scores don’t play with including recognisable themes as much as Bradley used to (he has a tendency to strongly “Mickey Mouse” the action), these films are still Tom And Jerry in look and feel. The first side is completed with Ah, Sweet Mouse-Story Of Life (1965), another short that demonstrates Jones’ ability to provide new visual twists on older gags, and so keeping the tradition of the series going.

Tom-Ic Energy (don’t you just love these title puns?) takes T&J out of the house and places them in the big city to continue their chase, with all that that entails, and starts side two off with cosy familiarity. Animation conventions are played with in Bad Day At Cat Rock, which returns us to the building construction site for some more clever visual tricks, and The Brothers Carry-Mouse-Off has Tom donning a mouse disguise so as to get closer to Jerry in another film that retains the atmosphere of the H-B shorts, though this one was only produced by Jones, being directed instead by storyman Jim Pabian. In Haunted Mouse, things get a little more inventive when Jerry’s magician mouse cousin (another one?!) comes to stay. Obviously Tom mistakes the trickster for Jerry, leading to some comic complications when the mouse conjures up a group of rabbits to mystify Tom. A fun diversion, this short isn’t the most densely plotted of Jones’ films, and fills out some extra seconds at the end by having the final title appear, for no other apparent reason, in several different languages!

Side two finishes up with two more shorts. The first, I’m Just Wild About Jerry, reminded me very much of the type of gag that Jones would use in his earlier Road Runner chase cartoons. One recurring joke in particular will stand out to fans of the Coyote: on chasing the mouse on roller skates, Tom’s journey eventually comes to a halt on a set of railway tracks – just in time to get a front seat view of the train’s headlights running straight for him! Finally, Of Feline Bondage plays with the old H-B idea of invisibility as seen in their earlier films The Invisible Mouse and The Vanishing Duck. This time around, Jerry’s fairy Godmouse takes pity on the poor little rodent after one too many beatings from Tom and gives him a potion that makes him disappear. You can imagine what comes next, though Jones’ slightly tamer direction means that some of the gags do not play off so well as those in the earlier versions, and the animation seems to make the objects come to life themselves, as opposed to the clever way the H-B cartoons really made the audience feel that they were still really “seeing” Jerry in a scene.

Side three finishes off 1965’s helpings with The Year Of The Mouse (Jerry and friend convince Tom that he’s a nut, only to get their own comeuppance in the end), The Cat’s Me-Ouch (featuring a tiny but dangerous mouse-sized bulldog) and Jerry-Go-Round, set in a circus and directed by Abe Levitow (though the “stop-start” nature of the opening titles is pure Jones). 1966 would prove to be Chuck’s major year with the cat and mouse, producing or directing eleven cartoons in the series. Duel Personality has an entire “pre-credits” sequence, leading to a very funny short in which the weapons of choice grow larger and more lethal as the film progresses! This one is also noteworthy for the fact that scoring duties are taken over by Dean Elliott who, while retaining Bradley’s theme in the openings, tries to bring some new recurring musical motifs to the series. The little mouse attacks Tom in his sleepwalking state in Jerry, Jerry, Quite Contrary, and in Love Me, Love My Mouse, Jones is joined in directing by Ben Washam. The two fashion perhaps the most surreal cartoon in the collection, with backgrounds reminiscent of What’s Up, Doc? as Tom floats over to his sweetheart to propose – only to have her take pity on Jerry! Puss ‘N’ Boats, directed again by Levitow, is another ship-set cartoon, with Tom not only after Jerry, but also having to safe himself from a hungry shark!

Over the course of the cartoons, one can see that Jones was itching to do other things just through reading his involvement in the credits themselves. He had already began to share direction with others on his crew, most notably Abe Levitow, and the cartoons began to hark back to the H-B films in story as well as theme as the ideas seemingly dried up. This becomes most apparent with the shorts on side four which, while not straight remakes, recycle many elements from earlier cartoons. In Filet Meow, Jerry befriends and saves from Tom a little goldfish (a similar concept to the aptly named Jerry And The Goldfish from 1951), and Matinee Mouse, directed by Tom Ray, becomes the first “highlights” cartoon in this collection, being made up of clips from Love That Pup and Jerry’s Diary (itself a compilation) from 1949, The Truce Hurts (1948), The Flying Cat (1952) and The Flying Sorceress from 1956. Hanna and Barbera are quite rightly given due credit, but it’s a little odd to see these clips re-scored and with new sound effects, though the concept of T&J going to a movie house to see their old films works well enough, even if the theater does show one of the CinemaScope cartoons in a pan-and-scan version!

Levitow’s The A-Tom-Inable Snowman is an Alps set chase, featuring a really fun co-starring St Bernard who comes to Tom’s aid with a beverage or two when Jerry gets the better of him. Jerry pits Tom’s wits against another cat in Catty-Cornered (another Levitow short, but scored this time by yet another composer, Carl Brandt), and the same cat joins Tom again to fight over Jerry in Cat And Dupli-Cat, this time directed by Chuck himself, who was attracted to the musical theme of the short, with Eugene Poddany back as composer.

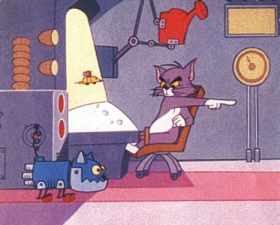

As Jones spent more and more time on other projects, he only contributed some gags and a producer role to the remaining cartoons in the series. Now mostly directed by Abe Levitow, these were a mixture of “tried and tested” routines and the “outrageously desperate”. Two films that smack of this are O-Solar-Meow, which places T&J on a space station of all things, and Guided Mouse-Ille (or, Science On A Wet Afternoon), where another set of high-tech gadgets play their part in the ensuing violence. There is nothing actually wrong with either of these two films, and they are very funny cartoons in their own right, but just do not feel like the traditional Tom And Jerry we’ve come to expect, though the Solar short does predate 2001: A Space Odyssey in some ways and also Star Wars by over ten years! The 2565-set Guided film also has some neat ideas, but there is something comforting about seeing T&J smashing the heck out of each other in a normal home that doesn’t quite work when they are substituted by futuristic robot version of themselves doing essentially the same thing.

Perhaps one of the most seen of these particular Chuck Jones films is Rock ‘N’ Rodent, which kicks off side five’s final set of cartoons from 1967. Directed by Levitow, it sets up that old chestnut where all Tom wants is a quiet night’s sleep, only to find that Jerry’s jazz band concert is to be held in Tom’s basement. Cannery Rodent (great title!) is another seafront set toon, directed by Chuck, and basically works as a continuation of the earlier Cat And Dupli-Cat, with a similar shark still pursuing Tom. Spoofing the hit television show The Man From U.N.C.L.E. is Levitow’s The Mouse From H.U.N.G.E.R. – which if not the all time best cartoon in this set, is most certainly one of the most re-watchable. The short has plenty of fun with spy-film conventions, setting up Tom as an ultimate agent from an Evil Enemy Agency. With more pace and sheer “zip” than many of the other Jones cartoons, this one is simply great fun, with Dean Elliott’s score easily bringing the U.N.C.L.E. theme to mind (that show was produced by MGM’s live-action division) and providing a smile on its own!

Purr-Chance To Dream, directed by Ben Washam, sees the return of Jerry’s mouse-sized pet pooch and for all intents and purposes is a sequel to The Cat’s Me-Ouch, while Levitow’s Surf-Bored Cat is set back on the beach, where T&J’s attempts to catch a wave are foiled by each other – not to mention an annoying octopus and that hungry shark back for more! Although we’ve seen this situation countless times before, this is probably the best of Chuck’s sea/beach films. Washam’s Advance And Be-Mechanized takes us, as the liner notes say, “back to the future” where Tom’s “robot-cat” takes another beating from Jerry’s mechanical mouse, in another cartoon that, despite its futuristic setting somehow feels among the most dated among this collection.

The series came to a natural end with Shutter Bugged Cat, a final “highlights” short (directed again by Tom Ray) that allows another look back through the concept of the duo checking through old film footage. Interestingly, the Jones team did not include any of their own recent offerings, relying instead on clips from the Oscar winning H-B directed Yankee Doodle Mouse (1943), Heavenly Puss (1949) and Designs On Jerry (1955), integrating them rather well with their new animation. Though it is not known if it was intentional or not, it does feel right to end the series with a film containing footage from the Yankee Doodle short as this was an early highlight itself, being the first Academy Award winning T&J film, and somehow brings everything around full circle even if, as before, watching these classics with Dean Elliott’s new music does feel a little uneven.

Fluidly animated, funny, and expanding on the original potential of the characters, many of the Chuck Jones Tom And Jerry shorts feel fresh and funny. They are a different take on the cat and mouse to be sure, but in re-mixing the formula a little, Jones revitalised the series and stopped it from outliving its welcome. Treating Tom and Jerry as almost human characters, such as Bugs, Daffy and Wile E Coyote, enabled the animators to place them in new situations rather than confine them to mostly just chasing around the house, though the future-set films possibly take it a little too far and lose a little of what we love about the characters.

These cartoons, though they may be slightly less frantic and not as fast-paced, look great here and have the finest prints in any of the three volumes. Sound, which is uniformly solid throughout all the sets, is also exceptional here, with many of the cartoons having the illusion of a real presence across the front channels. The Jones series ran for only five years, but they have been given the respect they deserve with this collection, rightly described by a Leonard Maltin quote in the liner notes as “the handsomest cartoons of the 1960s”, and certainly standing up to looking as “modern” in technique as today’s television animation.

Eventually, Chuck Jones’ Tower 12 was bought out by MGM and was re-branded as their own in-house animation production facility, MGM Visual Arts. After the Tom And Jerry cartoons ran out of steam, Jones developed his own ideas, winning an Oscar for his classic The Dot And The Line, as well as several collaborations with the UPA Studio (he had already written the feature Gay Purr-ee for them in 1962). At MGM, he created the highly successful TV specials The Grinch (1966) and Horton Hears A Who (1970), leading to his writing and co-directing the animated feature The Phantom Tollbooth, also in 1970. This feature would unfortunately do nothing to lift MGM’s ailing fortunes (the rest of the company was in a bad shape as well) and the Studio decided to permanently close down the animation department and cease all animation production for good.

For many, the magic of the Tom And Jerry shorts ended when Joe Barbera and Bill Hanna left the studio. While that is not entirely fair on the Jones films, it has to be said that theirs are the shorts and attitudes we think of when we see “A Tom And Jerry Cartoon” blaze upon the screen. Jones’ reinvention of the characters revitalised them for the time, but now remain slightly obscured by the renaissance of the original cartoons. Personally, I like the Chuck Jones shorts. I think they often feel more contemporary and fresh than some of the routine “beat ’em ups” of the H-B period. But at the end of the day, the cat and mouse were created by Hanna-Barbera and were best handled by them. These LD sets capture that essence better than any “greatest hits” compilation could ever hope, and certainly provide the kind of entertainment value and loyalty to the characters that one expects, and which was sorely missing from the flat and drab 1990s movie version and the insipid Tom And Jerry Kids TV project.

It would have been nice for completion’s sake to have had the handful of European cartoons included on a final disc in the third set, but the decision to omit these is overall a perfectly understandable one, and to be honest they are not terribly missed. It will, however, be very interesting to see how Tom and Jerry continue to make it to DVD. As we’ve seen with the Looney Tunes sets and the first volume of cat and mouse escapades, things do not seem to be chronological (or fully uncut for that matter), whereas part of the fun is in watching how these characters develop through their films. There are certainly some shorts in these sets (particularly the first) that I would be surprised to see re-issued fully uncut, and some if at all, as we have seen in the recent announcement that a fair few are to be withdrawn from television circulation. As for quality and quantity, well, I am sure that the DVDs would ultimately beat the spots off these earlier masters in terms of modern remastering techniques. But there is something pretty cool about knowing that you own every single Tom And Jerry theatrical short ever made, and in their proper ratios to boot. Watching them all in as few as sittings as possible, however, is an entirely different matter!