You are probably familiar with the Chiodo Bros, who created the animated prologue for Jon Favreau’s Elf several years back, and are longtime filmmakers in the field of stop-motion. Among many projects, Stephen collaborated with Tim Burton and Rich Heinrichs as a Technical Director and Animator for the acclaimed animated short Vincent, and Edward produced and co-wrote the cult classic Killer Klowns from Outer Space.

You are probably familiar with the Chiodo Bros, who created the animated prologue for Jon Favreau’s Elf several years back, and are longtime filmmakers in the field of stop-motion. Among many projects, Stephen collaborated with Tim Burton and Rich Heinrichs as a Technical Director and Animator for the acclaimed animated short Vincent, and Edward produced and co-wrote the cult classic Killer Klowns from Outer Space.

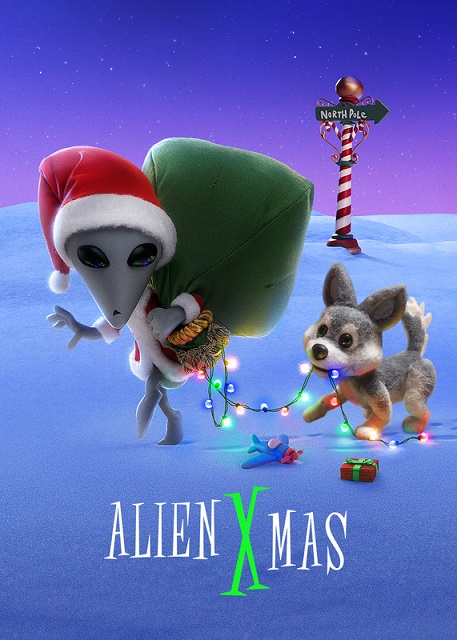

On November 20th, Netflix launches their latest creation, Alien Xmas, a delightful stop-motion holiday special inspired by the famous Rankin/Bass classics. Based on a 2015 book written by the Chiodos themselves, Alien Xmas finds a race of kleptomaniac aliens attempting to steal Earth’s gravity in order to more easily take everything on the planet. Only the gift-giving spirit of Christmas and a small alien named X will be able to save the world…

Indeed, that out-of-this-world touch brings a nice twist to classic holiday stories, which is no surprise, coming as it does from the talented Chiodo Brothers and executive producer Jon Favreau.

We had the pleasure to chat with Stephen and Edward about their instant classic!

Animated Views: What are the origins of the movie? The spark?

Stephen Chiodo: We always loved Rankin & Bass specials, the holiday specials like Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer (and) Frosty The Snowman,(plus) The Grinch, Charlie Brown, all of them. But the stop-motion specials that Rankin & Bass produced were always the ones we loved the most. And we always wanted to make our own holiday special. That’s what brought us into stop-motion.

Edward Chiodo: So, the actual circumstances: We happened to be doing contract work for ABC Family, doing bumpers and interstitials for their 25 days of Christmas campaign. We created a stop-motion Santa Claus and a bunch of props, doing little gags, little bumpers between their holiday offerings, and the executive we were working with kind of teased us with the idea and asked us if we had any holiday special ideas because she loved the technique and loved what we were doing. And there was an idea that was percolating in Stephen’s head that we developed into a pitch at that time, which was the basis for Alien Xmas.

SC: Again, we always wanted to do something a little bit different – a holiday special that hearkened back to the kinds of specials we watched as children, but with something different. I thought of something along the lines of Killer Klowns From Outer Space, because we like to mix genres. We thought sci-fi, with Christmas mixed in. That’s where I came up with Alien Xmas.

EC: So we developed a pitch for it, and we took it out. People loved the idea, but for business reasons it didn’t happen at the time. It was difficult to sell an original property. So, we essentially had all these assets, the storyline, the characters, their through-line, their arc, physical maquettes, sculptures of all the characters and all this presentation artwork. It was really the makings of a book. We then had an opportunity with an independent publisher called Baby Tattoo. Bob Self from Baby Tattoo fell in love with the idea and gave us a book deal. The book then became a really powerful sales tool. I mean, so many people go to producers looking for funding. It’s just an idea, but when you have a book idea that you present, it gives a little more confidence that it’s something that someone has already invested money in, and it kind of helped us go around the block with it. But still, an unknown property, new characters, it was a tough sell. So, we reached out to a good friend of ours, Jon Favreau. We had worked with him on Elf, for which we produced the stop-motion effects. We knew that Jon loved stop-motion, and we knew he was really enamored with the holiday, so we pitched it to him and he took to it. He saw what we were trying to do, saw the heart at the core of the story, and became an advocate and helped us sell it eventually to Netflix.

EC: Yeah, he was really a big fan of the technique, concept, and we stayed in contact with it over the years, and finally when an opportunity arose at Netflix, he brought us in, and he became our executive producer. He really helped shape the final story that you see in the special today.

AV: Can you tell us more about the making of the book you wrote together?

SC: I partnered with a scriptwriting friend of mine, Jim Strain, who wrote the original Jumanji screenplay. He and I cobbled the story together, based on my idea, and then we got my brother Charlie to illustrate it. It was a way for us to solidify the idea, as something more than a pitch, and it was something physical that we could hand off to people, which made it more valuable. We shared the book with Jon, and he really sparked to the idea. It was a tale of redemption, a Scrooge-type retelling, that type of Christmas tale, and Jon saw value in it.

EC: Jon’s involvement really came into play once we partnered and set it up at Netflix. He jumped in on the creative and helped us with the adaptation, molding it into a 40-minute stop-motion special, making sure we focused on the core story that he fell in love with, the simplicity of the characters.

SC: Quick side note, this was a feature film we were doing, and at one point we sold it to Relativity Media in the early 2000s. When the 2008 crash came, all the funding went out the window. So, I always had this feature length thing in mind. When we actually started to adapt it for a short, Jon kept coming in saying we should simplify, simplify, simplify, and kind of honed it down to its core. Jon was very instrumental in our creative journey.

AV: How did you get to the idea of associating Xmas and Aliens?

SC: Well, you know so many holiday specials are all about saving Christmas. I wanted something that would hearken back to what Christmas is really about, the secular Christmas story. And I thought, it’s just about the spirit of giving. That’s the core of it. And when we stripped it down – what IS the spirit of giving, what does it mean when you give a heartfelt gift to somebody – it’s really an expression of love. So, it comes down to a story of love and how we share love through the spirit of Christmas. And I reflected on the Black Friday sale happening in the United States, like for Thanksgiving people rush to the stores and they have these frantic, maniacal doorbuster sales, and to me, that was not Christmas. And that was the Klepts. The Klepts came out of that confusion at the Black Friday sales. They just grab, grab, grab, they want, want, want, but they don’t know how to give. So that was the core of the Klepts, and so I thought why not bring a new voice. Not an elf, not a reindeer, not something. Who could be the good nemesis? And I thought: aliens. Let’s bring aliens, a whole new vision. And then when I thought of aliens, I thought of spaceships. I thought, wow, these spaceships look like Christmas ornaments, and let’s make the mothership like a giant Christmas tree, so one thing fed into the other and we created this mythology about these Klepts that go around the universe stealing.

EC: One of the things we like to do here at Chiodo brothers, is that mash-up. Take two divergent genres or items and put them together in the same space and see what would happen. So, the alien inclusion here was really kind of a natural thing. They knew nothing about Christmas, but Christmas being so object-oriented in terms of gift giving, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to exploit that, and again (contrast it to) this nasty Klept “stealing” mentality.

SC: It’s an old story told with new cosmetics, new characters.

AV: How did you go from the book to the screen?

SC: The story is very simple, it’s only 16 pages, so we had to expand the characters and create little back stories for all of them. We had X being given as a gift; well, who gave the gift? We had Obie, and Obie has this incredible anxiety of producing this Super Sleigh by Christmas. So again, that tapped into, say, every working parent’s life of balancing work and family. So, we had to then really hone in and create those little issues for our main characters.

Santa Claus, the ultimate optimist, who thinks every obstacle can be overcome just by wishing it could happen. He learns a lesson, he entrusts Obie to build a Super Sleigh by his deadline, but it was an impossible task. He realizes in the end that he put Obie in a horrible position. So, these are the things that came out of our simple story.

EC: Again, in terms of the process, we had bigger visions, and you want to start filling in all those extra characters; and what that starts to do, is expand the story. We worked with Kealon O’Rourke, the first writer on the project; and then, with Jon’s tutelage, we were able to hone down all these great ideas, all this great action and funny bits, and figure out what the core of the story was.

AV: What led you to stop-motion? What do you like the most in that form of animation?

EC: The natural thing with stop-motion is that they are little toys on miniature sets, and it goes hand-in-hand with Christmas. And Christmas and stop-motion always go together in our minds, that’s what we grew up on. Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer, Santa Claus Is Coming To Town, Rankin & Bass classics. Even the Norelco shaver commercial with Santa on a shaver zipping through snow banks and things. It’s just a very comfortable feeling. They go hand-in-hand together. So, the opportunity to bring this story to life in stop-motion is a very organic thing.

SC: And what’s good about it, is that it really truly is magic. The audience knows that these are inanimate objects, dolls and puppets on a stage; yet, they come alive magically through stop-motion, and I think that’s the attraction. These are real objects that come alive. It’s magic.

EC : Again, we emulated the Rankin & Bass styling, upped it up a little bit production value wise, and what they were able to do in the 60s; but we didn’t lose the hand of the maker, that was really important for us. You feel that these are hand-crafted items telling this story, real characters on a miniature set, as opposed to a computer-generated version.

AV: How did you come to work on Elf?

SC: Well, it’s these connections. We were working within the industry, and you kind of meet people along the way. We were co-producers on Sid & Marty Krofft’s Land Of The Lost, we were producing the animation effects. We hired a young cinematographer/cameraman named Joe Bauer, and he was great.

EC: It was one of his first jobs in the LA area. He moved to Hollywood to pursue his career, and we hired him.

SC: And that was it, Joe was off; and then all of a sudden, we get a call from Joe Bauer – he’s working with Jon Favreau on Elf.

EC: He’s now a top-notch VFX Supervisor, and when it came to talking about Elf, Jon was really passionate about stop-motion, and having the North Pole sequence emulate Rankin & Bass, and he was talking to Joe about, “Who could do this? Who gets this?” And he says, “You’ve got to talk to the Chiodo Bros.”

SC: So it was Joe Bauer who introduced us to Jon through Elf, and that started the collaboration. It was great working with Jon. He really got it. His love and affection for stop-motion is the same as ours. He saw it when he was young, it was a major part of his early childhood, and it’s magic. And again, we tried very hard to duplicate the Rankin & Bass style, and I think it was the introduction of the arctic critters and that stop-motion world at the beginning of Elf that brought us into this familiar holiday spirit that made the rest of the film work when they went to New York. That’s what Jon wanted to see, and I think we really helped him create that. So, there we were, creative partners at that point. So, once we knew Jon and understood what he liked, we had all these little ideas that we wanted to pepper to him over the years.

EC: It was great, because we weren’t just talking on a tech level, even with Joe Bauer, we were talking about the characters and the emotion. Even though we were a contract company on the job, it’s what we do. We came to Los Angeles to make movies, to be involved in that level of conversation; and get into the head of the director, what he wanted to achieve emotionally. It was just a rewarding process for us. And really got to clue into the brilliance of Jon Favreau, his creative mind, and how he pursues his projects, how he breaks it down and executes.

AV: How did you translate the Rankin & Bass influence into your film?

SC: The Rankin & Bass style is like uber sweet and genuine and cute, and they’re little dolls, and it makes you feel kinda good, so we wanted to contrast that a bit with our evil aliens. So, we made our elves really cute, really sweet, so we had this greater contrast between these nasty little grey, colorless aliens against this really sweet, magical Christmas world. So, we kind of accentuated everything that Rankin & Bass did, and made it even more festive.

EC: There’s a simplicity to the design, the staging, the action of Rankin & Bass that we emulated on its core, but we expanded that. But really in terms of having fun with the genre, we love the holiday specials, and we wanted to have a little fun with them. Be a little self-aware of the genre we were emulating here. So, there’s a little poke at the genre here and there, but it’s done in a really loving way, because we really love the genre.

Building on the R&B style, we explored a lot of different character designs – some more complex, some more simple. Working with James Baxter at Netflix, he helped us hone in on what was true to R&B and what would work and support the story best. Stephen had done a lot of research and a lot of inspiration for Christmastown, and a lot of art, a lot of research, a lot of development went into this.

SC: When it comes to the town, I was trying to think of Christmastown, what would be the architecture, what’s the classic image. In Rothenberg, Germany, there’s a town there that they call Christmastown. And when I researched it, it’s what I think Walt Disney used for the original Pinocchio cartoon, it had that kind of hand-built, Tudor-type buildings. That seemed to resonate with everybody as a Christmas town. And then it was the colors of the town; we wanted to create a North Pole village that was warm and cozy. So, we had orange lights emanating from the town, in contrast to the cold purples, magentas and blues of the outside world. So, it’s a cold world with these warm cottages. So that was the art direction for the town. And when it came to the Klepts, they were the opposite. They were void of all color. Because of their greed, their color had faded away. So we had these grey aliens, but we couldn’t have grey ships, because grey on grey wouldn’t show up, so we had to design the interior of the space craft with a little tinge of color. What’s the best alien color? Green. So, there’s a little bit of green in the space ships to contrast against the grey aliens. But then the green became a centerpiece for later in the show when the ships turned into Christmas ornaments. So, it’s really funny how that creative process works and fed upon itself to create I think what is essential to the story.

EC: And then in terms of the movement again, R&B: very simple graphic design. Simple setups. We built upon that in terms of… it would be tough to watch 40 mins of true R&B style now, I think we have fonder memories of what it really is, which is fine. So, we just refined the technique a little bit in terms of the styling, the execution, and the art department. We had a great art director, Jeff White, who worked with a team of really incredible artists. All the food was sculpted and painted by hand, truly amazing, all the detail.

SC: And Becky Van Cleve was our head of puppets, and she created a slew of puppets, so many puppets, from Santa Claus, to the elves, to the Klepts, and SAMTU, the robot, a very special character. All done by a staff of maybe 20 people.

AV: Can you tell me more specifically about the character of X? As he can’t talk, and hasn’t many elements on his face, it looks like nothing helps to make him expressive. And yet, he’s so easy to connect with. How did you approach him, animation-wise?

SC: That was a real challenge. We looked to our silent screen stars. Actually, we looked at Buster Keaton as the inspiration for X’s performance. All pantomime, all mime and movement rather than dialogue. A lot of the gags in there that were specifically a riff on Buster Keaton, who represents the Everyman. The Everyman against the world. The little guy. And I think that’s why we root for X. Not having him speak was one of Jon’s suggestions, one that kind of took me by surprise, but I embraced it as a challenge, and I think it worked out for the best.

EC: And the idea of how to express without speaking, it’s obviously physical gesture, body positions and things, but then we had a series of really expressive eye shapes that were replacement animation that the animators did during performance, and then mouth shapes that were done in post digitally. But it’s really the acting that the animators did, in conjunction with the eye shapes that really create the emotions that we see him in.

SC: And to top it off, to seal the performance was Dee Bradley Baker’s sound, his sonic performance adds that little bit of insight into the emotional tone to support the movements. So again, it’s a collaboration between a lot of different people.

AV: From the technical point of view, what did you take from these productions and what changed since then?

SC: Technology has really added so much to stop-motion in general. Jamie Caliri has designed this software called Dragonframe which allows the stop-motion animator to watch his/her performance while they’re animating through an onion skin-type review of the footage. So at the end of a shoot, you know you have the shot, where previously shooting on film, you’d have to shoot, send it to the lab, wait for it to come back the next day and you really couldn’t move production ahead by tearing down the set until you knew the shot was accepted. That’s all changed now with technology. Shooting digital, shooting on the Dragonframe software, you know what you have the moment you finish the shot, so you move production on more quickly. Major technological advances.

EC: What hasn’t changed, is that it’s still a handmade movie. Everything you see in that show is done by a team of artists, sculptors, mold makers, casting people, seamstresses, tailors, electricians, carpenters, everything is handmade; and at the end of the day, I think the most important thing, our actors are still moving the puppets/characters frame-by-frame. That hasn’t changed since animation started over 100 years ago, it’s still a frame-by-frame, hands-on process.

AV: As FX specialists, how did you approach the film FX-wise?

SC: That’s where these new digital tools come in really handy. We did have an opportunity to shoot elements sometimes, we’d shoot characters or props against green screen, composite them later. That kind of manipulation you can do in digital post did help us with some of the timing that enabled us not to have to do reshoots all the time. 98% of the footage in the show are first takes.

EC: It’s funny, in the old days, doing stop-motion animation, if the character had to jump in the air or float in the air, you would hang the puppet on wires, and that just inherently added so much time and difficulty to executing a shot. Now we use much more solid support, rods and hard wire, rigs to hold up puppets and suspend them in the air. And with digital technology, we’re able to go back and remove all those rigs (“rig removal,” it’s a pretty common term in all sorts of movie and TV production now). The technology frees up the animator from the drudgery of the technical, of trying to steady a puppet, or wait for it to stop moving, they can just focus on the performance, because they are our actors. The technology has really opened up a whole new world for performers who may not otherwise have taken to the technique. Now more than ever, there are more people doing stop-motion at a level that’s never been seen before.

AV: How did the production go?

EC: We started writing the script in Fall of 2018, we started pre-production in April 2019, started shooting in June of 2019, and finished up right before the Christmas holiday at the end of 2019. In 2020, we were in post-production, got slowed down by Covid quite a bit, and then delivered the show in August. All in all, it was almost two years of production. But internally at Chiodo Bros, we had started working on it in early 2018, so it’s been two solid years of work for us, but actual production was just over a year, year and a half. We had over 200 people in fabrication and production working during the course of the production, a high-water mark at any given time was just over 100 people. By the time we add on all the production people, the marketing people, we were probably over 300 people that worked on this 40-minute movie. It really takes more than a village; it takes a small army. We did all the building, design and test shooting at our studios in San Fernando; but when it came to actual production, our facility just wasn’t big enough, so we went to another company who are friends of ours, Bix Pix in Sun Valley, who had some down time on their stages. So, we rented their facility. We had 16 stop-motion stages that we were shooting on, anywhere from 8-12 animators working on a daily basis, constant setup. It was quite the undertaking.

AV: Can you tell us more about your studio?

SC: It was founded in the early 80s as a stop-motion studio, but the technique wasn’t really in vogue then, Directors wanted to have live special effects, like ET or the Gremlins, animatronic puppets, so they could direct them with live action actors. So, we switched gears, we started getting into animatronics and all those different kinds of effects. At the core of our company, we were always a story generating company. A character company, designing characters. We would design characters that were then stop-motion or CG, or puppets, or animatronic. At its core we were character designers and creators, after all we came to LA to make movies and tell stories. So, we stayed afloat using our art skills and producing skills as an effects company, until we could get some of our ideas funded and produce our own work. That’s Chiodo Bros.

EC: The stop-motion was always a critical part of what we did, and it was always the dream of doing more stop-motion and bringing stop-motion back as an entertainment form, and possibly as effects in movies, like on Elf.

AV: What were the challenges of the production?

SC: I’d say for me as a director, producing quality performances given our schedule. It’s interesting – it’s an army of artists and technicians that mount the production, so before we get to directing the performances, you’ve got the art department setting up the stage, the lighting department doing the lighting, the DP with the camera, all this technical stuff that really takes the majority of the time. And then when it’s all set, then we animate. And that’s when I can step in and direct some of the performances. And then it’s the animator. And when you think about it, more time is probably spent setting up than under the camera moving the puppet, because of the magnitude, the scope of the sets and the production. That was a challenge for me, to get out there quickly and efficiently and effectively when the right time was to give the direction and get the performance done.

EC: And just from a logistics standpoint, dealing with 100 people working in two different facilities is just a huge logistical nightmare, and just making sure everyone has what they need in terms of direction, materials, resources all around. Luckily, I had a great production manager in Eileen Kohlhepp, who really assisted in that manner. Probably one of the biggest hurdles on this was, this was originally supposed to air in 2019, and when we started the production, we were on an accelerated schedule to make that happen. But when it came down to it there wasn’t such a huge rush to get it “on air,” Netflix is not like a network, it’s a different type of thing, streaming. They told us to slow down, relax. We still had financial things so we couldn’t stop production, but it really gave us the time to stop, retool a little bit, catch our breath and put the best product forward. So that was a good call on Netflix’s part. They saw what we were doing, what we were trying to do, and it is hard…to have that many people trying to stick to a coherent vision. They saw that we needed the extra time and gave it to us. They were a great partner in that respect.

AV: What will you keep from that experience?

SC: The hope that we might have created the kind of holiday entertainment that will last, like Rudolph has lasted with us. That people will sit down together and watch this year after year. That would make me feel really good, the satisfaction of a holiday family experience that they can share together.

EC: That’s what this is for me. I had this when my kids were growing up, and even now that they’re older. The family tradition was always to watch Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer, Santa Claus Is Coming To Town, Charlie Brown Christmas, How The Grinch Stole Christmas, when they would air on network television. We owned the videotapes and DVDs. There was something about sitting down as a family and watching them as our holiday tradition. It was really important, so for me, the hope is that maybe we could enter that place in people’s hearts, that they would want to watch it every year with their families, and share it with the ones they love.

AV: By the way, do you have a problem with a certain Swedish ready-to-assemble furniture company??

Both: No! It’s funny, it’s a universal joke, the thinnest instructions with one tool to pull it all together. If you think of an insurmountable task, I think everyone on the planet knows what that means. Everyone at some point in their lives has had to put together an Ikea bookcase.

Be sure to watch the Alien Xmas trailer: Click here.

With very special thanks to Stephen & Edward Chiodo and to Fumi Kitahara