After the death of Walt Disney in 1966, the absence of the prolific founder left the animation team without creative leadership, forcing them to redefine the artistic direction of the studio.

After the death of Walt Disney in 1966, the absence of the prolific founder left the animation team without creative leadership, forcing them to redefine the artistic direction of the studio.

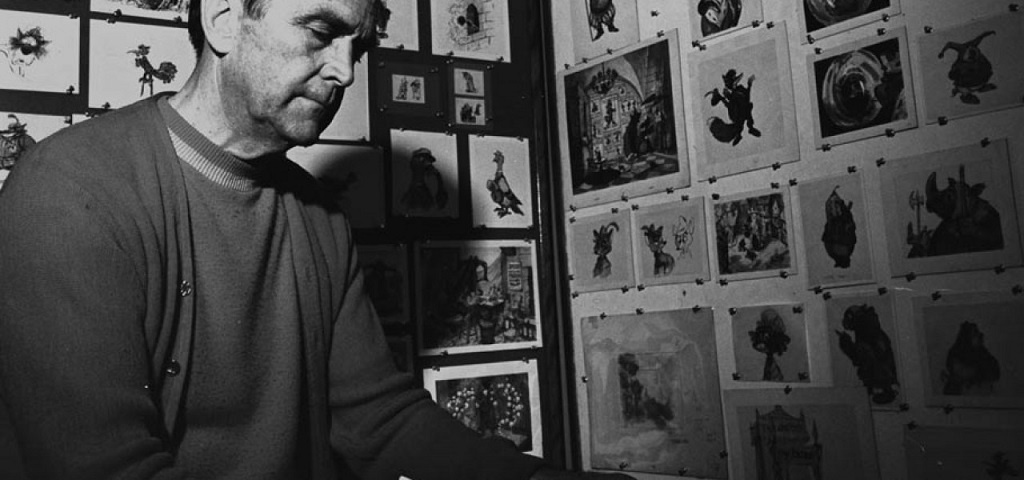

Animation legend Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman spearheaded this age of renewal with two key goals: training the next generation of artist and animators, while also developing enduring characters and stories. He placed this latter responsibility in the hands of two chief “concept artists”, Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw, who together became two of Disney’s most influential visual development artists.

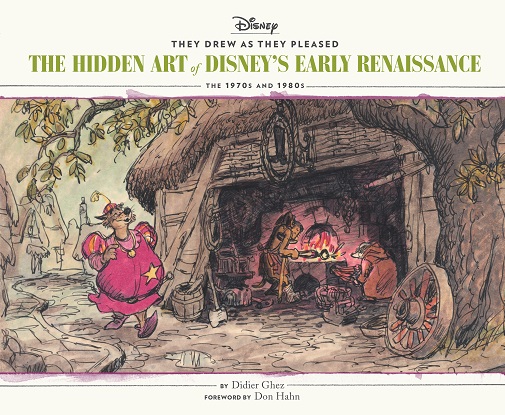

Every book by Didier Ghez is an event in itself. But this one is certainly his most personal one. Filled with dozens of never-seen-before concepts for such classics as The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, Robin Hood and The Rescuers, the book is not only one of the most beautiful ones of the series, but also – through Didier’s in-depth research, vivid descriptions and illuminating interviews – one of the most touching ones.

It offers a rare view of the Disney Legends who helped shape the nature of character and story development in the 1970s and 1980s, and prepare for the Disney animation renaissance of the 1990s.

AnimatedViews: Your books wouldn’t be that magical if you hadn’t a special connection with Disney history, art, and artists. But this one seems even more special, and even more personal. You evoke that in your introduction, but can you tell us more about your personal link to the features of that time, the ‘70s and early ‘80s?

Didier Ghez: I was born in 1973, the year Robin Hood was released. When I was a kid (before VHS and way before DVDs), my father bought 16mm reels which featured scenes from The Jungle Book, The Aristocats and Robin Hood. My brother and I grew up watching those. At Christmas, we would also watch the special Disney programs, including the one focused on the upcoming feature The Rescuers. Needless to say, I have always had a soft spot for the animated features of the 1970s. This might also explain why, thirty years ago, the first two Disney concept artists who caught my attention were Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw, men who largely defined the style of Disney’s animated features in the 1970s and early 1980s. As a young teenager, when I discovered Ken Anderson’s character designs for Robin Hood in the first edition of the book The Art Of Walt Disney by Christopher Finch (Harry N. Abrams, 1973), I sensed that one of my life goals would be to see all the art that Ken had created for that movie. And when I first saw Mel Shaw’s concept sketches for The Black Cauldron in the various articles that had been written at the time, my interest in the film, not yet released, immediately doubled. In the mid-1990s, I started collecting artwork by Ken Anderson, who, along with Mel Shaw, has remained my favorite concept artist to this day.

Which explains why writing this specific volume of They Drew As They Pleased – The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Early Renaissance, has been my life-long goal. There is no volume in the series I am prouder of.

AV: How do you explain that the features of that time are considered less successful than the others, that being fair or not?

DG: One of my most enduring frustrations over the years, while reading books about Disney history, is that most of them discuss the Disney features until The Jungle Book (released in 1967 — the last feature that Walt personally supervised) then jump to The Little Mermaid (1989), with nothing in-between. The authors seem to think that the Disney features from the 1970s and early 1980s are not even worth mentioning.

When Walt passed away in December 1966, close to a year before the release of The Jungle Book, the Disney Studio had to find a new leader. Director Woolie Reitherman, a former pilot during WWII, was a born leader, and he was the one who took the helm. He had some tough decisions to make, however. The costs of producing animated features kept going up, master story artist Bill Peet had left the Studio during the making of The Jungle Book, and the team Woolie had at his disposal was mostly a team of very strong animators. All those elements pushed him to simplify the stories and to start relying chiefly on endearing characters. After all, within the team that remained at the Studio in the 1970s, he had Ken Anderson, a jack-of-all-trades, who was the best character designer the Studio had ever seen since the time of Jack Miller, and, in Animation, veteran animators John Lounsbery, Eric Larson, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and Milt Kahl. So, in the absence of Walt, focusing on very strong characters and on their interactions, instead of trying to develop very strong stories (Walt’s forte), made sense.

The result was that the movies are weaker narratively that those of Walt’s era, but delightful when watched sequence by sequence. The characters are unforgettable and many scenes are etched forever in our minds. The reason I love them so much is because I absolutely adore the characters that they feature and because I find many of the sequences that they contain to be absolutely timeless, like “Everybody Wants to be a Cat”.

AV: Your book focuses on the lives and art of two major Disney artists, Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw. How would you characterize their art?

DG: In the 1960s and 1970s, Ken Anderson was first and foremost a master at character design. From The Jungle Book to The Rescuers, he drew hundreds and hundreds of characters, most of whom did not make it into the final movie. The incidental characters that he designed for Robin Hood, and whom you will discover in this book for the first time, are particularly memorable and I would have loved to see more of them included in the movie. By the way, the boxes at Disney’s Animation Research Library that contained those drawings had not been opened since 1973. I had dreamt of seeing what they contained since I was a teenager. When the first one was opened and when I saw all the masterpieces it contained, I started crying. I had been waiting for this moment for over 30 years.

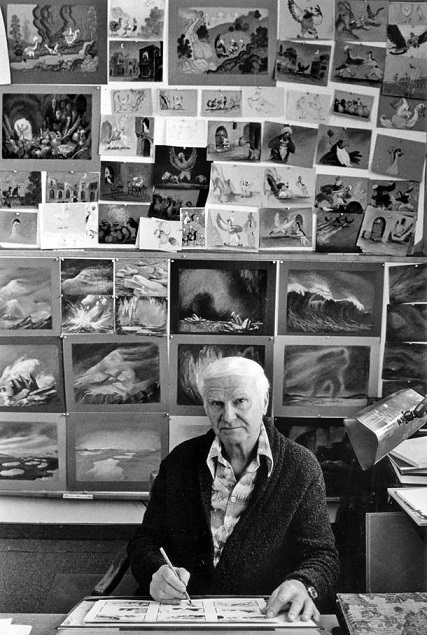

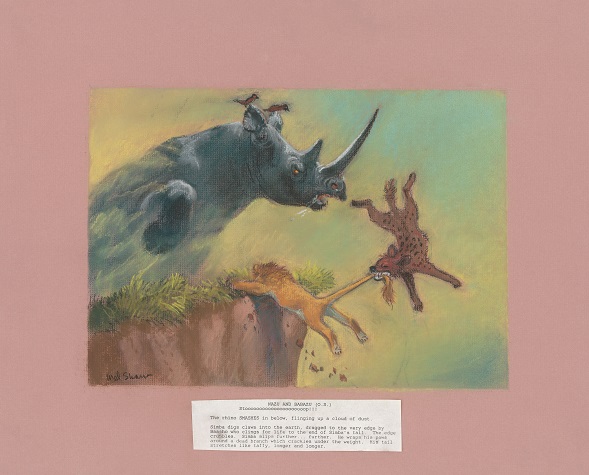

As to Mel Shaw, his artwork can conjure up a whole scene in just one drawing. In many ways, it has the same power as the drawings Marc Davis created while at WED (now known as Walt Disney Imagineering): the composition is so strong and the characters so expressive that they seem to be alive on the page. And Mel’s use of pastels makes those drawings even more special, of course.

AV: What’s interesting about them is that they didn’t have just one job at Disney. They took on so many different roles, with the same talent. Can you tell us about their versatility?

DG: You are correct. Both Ken and Mel started as animators in the 1930s but soon moved into other directions for which they were more suited.

Mel started as an animator at Harman-Ising; but when he joined the Disney Studio, he was already a story artist. At Disney, in the 1930s, he also drew a proposed adaptation of Song Of The South in comic book form, which was eventually shelved. He left the Studio in the 1940s and came back in the 1970s, by which time he became a visual development artist.

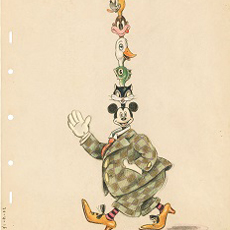

Ken’s career was even more varied. There is a reason why Walt called him a “jack-of-all-trades”. He was an animator, then a layout artist and a character designer. He also worked on the theme parks (from Disneyland to EPCOT!), and even on the first animated cartoons produced for the Disney Channel in the early 1980s. When you look at all the Disney artists, his career is probably the richest and the most fascinating.

JN: You revealed not only magnificent art used for Disney classics, but other pieces made for projects that didn’t make it to the screen. Can you tell us about some of those?

DG: The more I conduct research about Disney history, the more I realize that you really cannot understand how the movies that made it to the screen were developed if you do not have an in-depth knowledge of the projects that were eventually shelved. All those projects are closely interconnected.

Catfish Bend is a good example: throughout the 1970s, Ken Anderson was trying to adapt this series of books by Ben Lucien Burman to the screen. In order to do so he developed dozens of beautiful characters who lived in a Southern bayou. When the project was shelved, many of those characters became protagonists in The Rescuers!

Another of my favorite projects, among the ones that were shelved, is Chanticleer And Reynard The Fox, which both Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw tackled at some point or another. The character designs by Ken, once again, jump out of the page, and the musical sequences featuring insects that Mel dreamt up are among the most memorable in the book.

Finally, you will not be surprised to hear that I am fascinated by Musicana, the proposed “Fantasia sequel” that Mel Shaw and Woolie Reitherman were championing in the early 1980s. I love the pieces of music that they had selected and couldn’t stop staring at the art pieces that Mel created to pitch the project. I really wish that one had made it to the screen. By the way, one of the most stunning discoveries I made while researching the book (in terms of written documents) was that of a story conference between Mel Shaw and Woolie Reitherman about Musicana. This is the only known story conference on the subject and I had the pleasure of unearthing it in the collection of one of Woolie Reitherman’s sons.

AV: How helpful were their families in your research?

DG: The families of both Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw were immensely helpful. Ken’s three daughters allowed me to scan all the documents their father had kept and so did the family of Mel Shaw. And it was not just Ken’s or Mel’s artwork. Among Ken Anderson’s collection was a series of early character designs by Tom Oreb for Sleeping Beauty, many of which are reproduced in the 4th volume of They Drew As They Pleased, as well as several concept drawings by Tyrus Wong for Bambi.

The massive Mel Shaw collection contained hundreds of pieces of artwork, but also a three-page written document from the 1930s which listed a series of abandoned Disney shorts, along with the story artists who had suggested the ideas for those shorts. Pure gold from a historical standpoint.

And then there was Bruce Reitherman, one of Woolie’s sons. Bruce had prepared some beautiful drawings by Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw for me and my friend Joe Campana to scan. At the end of the session, I asked him if his father had preserved any written documents by any chance. “You are interested in written documents?” he asked. “I have four boxes full of them.” When we started opening these boxes, I could not believe my eyes. They were full of documents from the 1970s and early 1980s that did not exist anywhere else, including this story conference between Mel Shaw and Woolie about Musicana, early treatments for a proposed Mickey Mouse feature and much more. But the highlight was a document from the 1930s: a 66-page document from Disney’s Story Department which listed proposed story ideas for Disney shorts, complete with the dates when they were submitted and the names of the artists who had submitted them. I almost fainted when I realized what I was holding in my hands: I knew that this document did not exist anywhere else and that it was bridging hundreds of important gaps in our understanding of Disney history.

AV: I couldn’t help noticing that many of the projects Ken and Mel worked on were based on music, like Fantasia and Musicana. Also, Mel Shaw was driven by music when drawing the opening of The Rescuers, and played Carmina Burana during a story presentation of The Black Cauldron. Can you tell us more about their link to music?

DG: More than Ken, it was Mel whose career was especially linked to music. His very first project at the Disney Studio was “Flight Of The Bumblebee” a proposed sequence for the project that would later one become Fantasia. And you are correct, one of his last projects was the 1980s proposed Fantasia sequel, Musicana.

What I found particularly interesting, while researching Mel’s career, was that I realized that we knew almost nothing of the Disney Studio’s early work on Fantasia. We knew that Walt and his artists were developing “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” at the end of 1937; and that by the end of 1938, Dick Huemer and Joe Grant were helping Walt select pieces of music for Fantasia; but what I had not realized is that, as early as February / March 1938, the Studio was already very actively researching and developing sequences for Fantasia (which was not yet known as Fantasia at the time), starting with “Flight Of The Bumblebee.” In fact, I am still making discoveries in that respect. I just learned, for example, that in early 1938, Disney’s Story Research Department was pitching the possibility of using Wagner’s “Rite of Nibelungen” to tell the story of The Hobbit!

JN: How is Volume 6 coming along at the moment?

DG: The final volume in the series, They Drew As They Pleased – Volume 6 (The 1990s to the 2010s), will focus on the art and careers of artists Joe Grant, Hans Bacher, Mike Gabriel and Michael Giaimo. The chapters are written, and the artwork has been selected. If all goes well, the layout will be created before the end of the year and the book will be released in August 2020. As always, more than ninety percent of the artwork has never been seen before in book form. And the chapters about Hans Bacher, Mike Gabriel and Michael Giaimo are particularly lively since I was able to speak with all three of them. As to the Joe Grant chapter, it will reveal a lot about some of the most obscure projects he worked on, and since Joe started working at the Studio in the 1930s in the same office as Albert Hurter, we will have come full circle.

They Drew as They Pleased – The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Early Renaissance is available to order from Amazon.com!

With very special thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney.