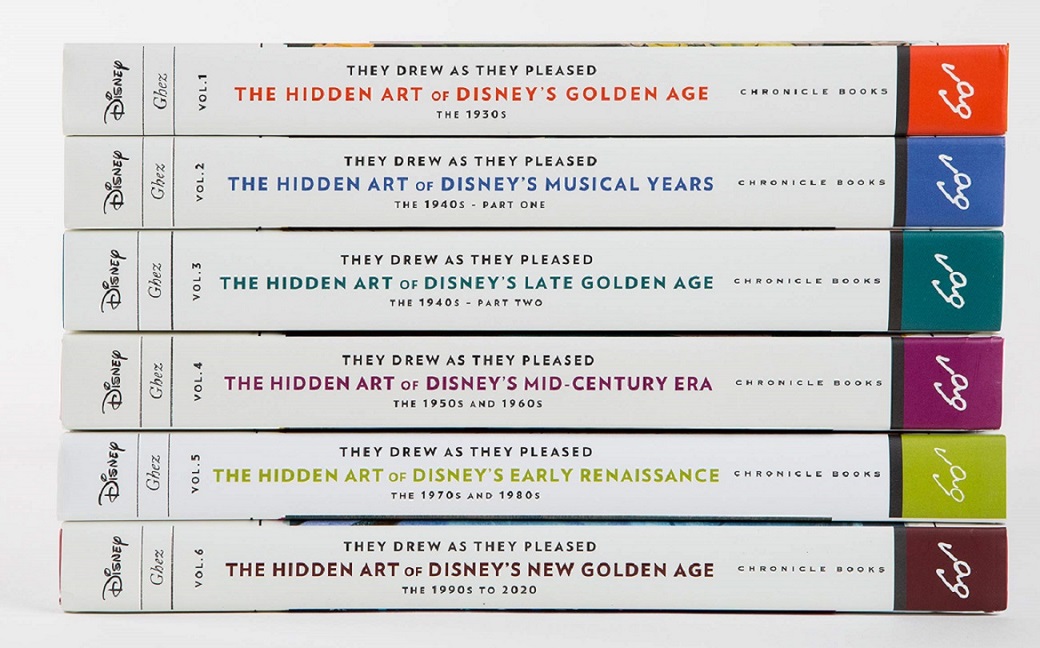

In 2015, historian Didier Ghez authored They Drew As They Pleased Volume 1: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Golden Age, focusing on the studio’s first decade in the 1930s. It began an ambitious project to document the history of Disney animation by focusing on concept art and concept artists.

In 2015, historian Didier Ghez authored They Drew As They Pleased Volume 1: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Golden Age, focusing on the studio’s first decade in the 1930s. It began an ambitious project to document the history of Disney animation by focusing on concept art and concept artists.

Through extensive research through the Disney Archives, and personal connections he made with animators and their families, Ghez uncovered a trove of previously unpublished artwork, history, and anecdotes which give an unprecedented view into how the films, characters, storylines, and unique Disney look and feel came to be.

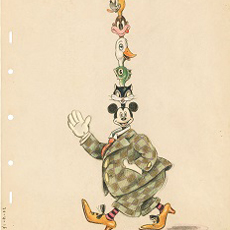

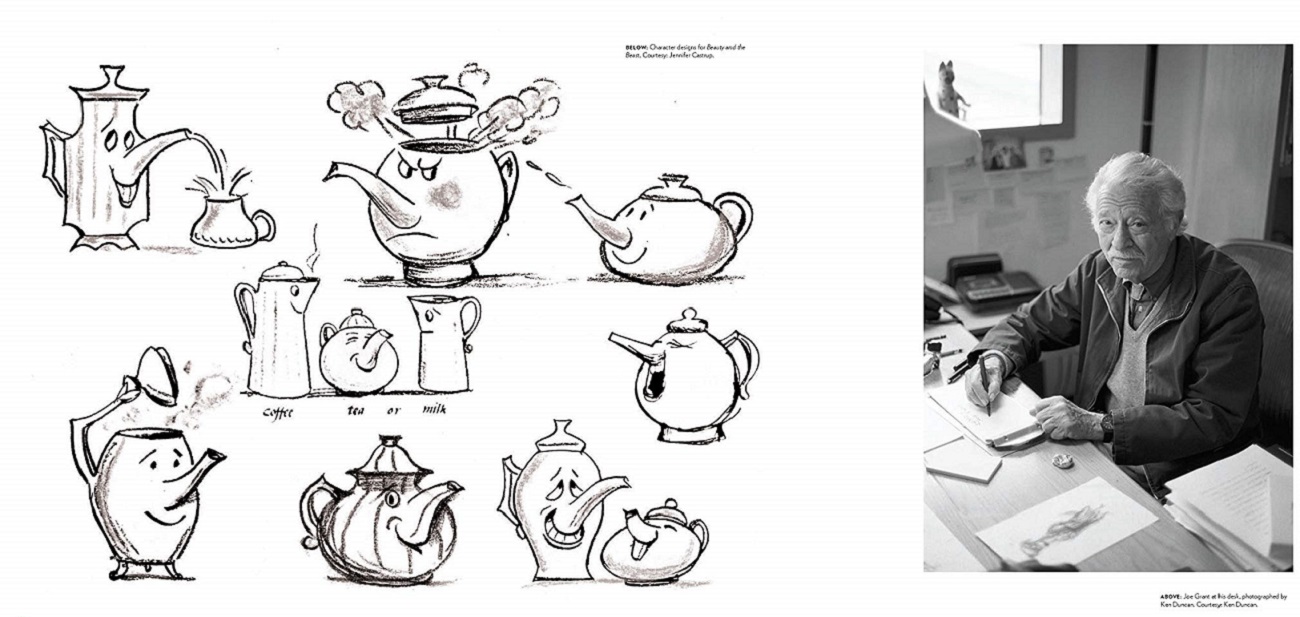

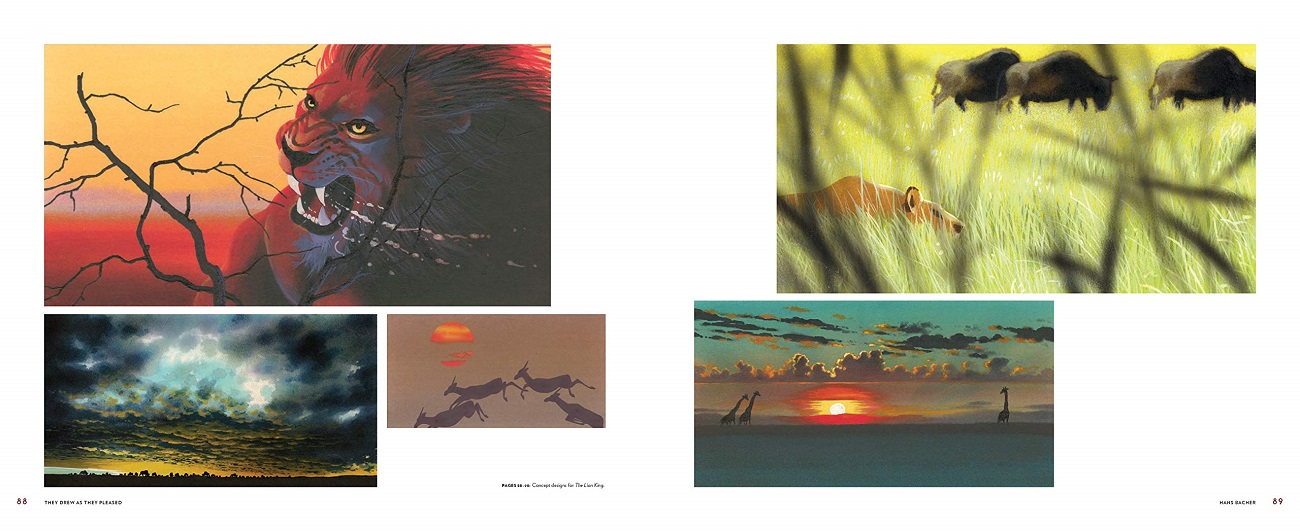

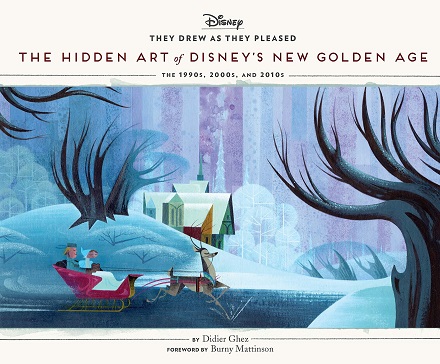

The sixth and final entry is now being published, titled They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s New Golden Age. It focuses on the 1990s through 2010, when Walt Disney Animation Studios experienced a dramatic creative shift as advancements in digital technology gave rise to computer-generated animation and produced blockbuster hits like The Little Mermaid, Beauty And The Beast, The Lion King, Tangled, Wreck-It Ralph, and Frozen. This volume highlights artists Joe Grant, Hans Bacher, Mike Gabriel, and Michael Giaimo, whose collective talents exemplify Disney’s storied past and visionary leap forward into the New Golden Age.

Didier Ghez tells us more about his adventure and the last chapter of this extraordinary project.

AnimatedViews: Can you tell me about your feeling now that we come to the last chapter of the project?

Didier Ghez: I have to admit that my feelings are mixed: I am delighted to know that I was actually able to complete the series and grateful to the publisher, Chronicle Books, for supporting this endeavor until the end. At the same time, having lived day in, day out with this project for six full years, it feels weird not to be working on it anymore. I will miss the ongoing discoveries, awesome surprises and moments of elation when questions I had asked myself for years were finally answered or when a piece of concept art that I had thought lost forever would suddenly be rediscovered. I have so many other projects that I am eager to tackle, though, that the feeling that wins out is sheer happiness to have been able to tell this story, in depth and the way I wanted to tell it from the start: through the testimonies of the artists themselves and of the people who knew them.

AV: It’s been six years now since you initiated that incredible award-winning project. What a journey!

DG: As I mentioned in a previous interview with you, I realized many years ago that what really fascinates me when it comes to Disney are the artists and the whole creative process. The creative process is at its most intense when the story is being invented, and when the characters and locales are being designed. So, the closer you get to the designers and the story artists – in other words, the further you are from the finished shorts and features – the closer you are to the crazy ideas that are being invented to give birth to the animated cartoons we love.

It was therefore critically important for me to focus on the concept artists to understand this chaotic and fascinating creative process.

One last reason why this series of books is so important for me, is that, since this is an official Disney project, I was able to share not only brand-new information in the text but also hundreds of never-seen-before visual documents. Eighty per cent of the more than 400 visual documents displayed in each of the volumes in this series are presented here for the first time. The same is true with most of the information in the text. There is barely any duplication with any books about Disney released in the past. I was clearly trying to break new ground and to move beyond John Canemaker’s spectacular book on the same subject, Before the Animation Begins.

I knew from day one, when I pitched the concept of the series to Chronicle Books, that I would need at least five volumes to tell the story in the amount of detail that I had in mind. While I was writing Volume 1 (the 1930s), I realized that I would never be able to discuss the 1940s in a single volume (too many great artists, too many fascinating ideas) and I therefore convinced Chronicle Books to allow me to add one more volume to the series. Thankfully they were supportive (but made clear that they would not go beyond 6 volumes).

When Chronicle Books approached Disney about the project, both the Walt Disney Archives and The Animation Research Library were immediately enthusiastic. The series would not be half of what it is without their support. They understood my vision from day one and went way beyond the call of duty to help me in any way they could.

Many historians also shared research documents with me, including Michael Barrier, John Canemaker, J.B. Kaufman and many others. And, of course, the series would not exist if it weren’t for my good friend and fellow Disney historian, Joe Campana, who hosted me during my research trips and tracked down for me the families of many of the artists who are discussed in the books.

AV: Why is this period called “The New Golden Age?”

DG: After Walt’s death in 1966, Disney’s animation studio lost a little of its mojo in the 1970s and early 1980s, the low point being the disappointment of The Black Cauldron. When a new management team came on board in 1984, led by Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Roy E. Disney, it was not clear that the Animation Department would even be kept alive. Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988 and The Little Mermaid in 1989 changed all this. It felt like the Disney Studio was back at the top of its game; and Beauty And The Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King confirmed that impression. It was really the start of a New Golden Age for Disney, half a century after the Golden Age of the 1930s.

AV: How did you come to focus on these four artists? Would you please characterize briefly each one’s style and personality?

DG: This sixth volume of the series covers three full decades, a period of time when dozens of talented concept artists worked for Disney. It was therefore extremely difficult to focus on just four of them and to decide who to include in the book.

The first chapter focuses on this outstanding Disney Legend, whose Disney career began in the 1930s and came to an end in the 1990s. At the start of his career, Grant worked with Disney artist Albert Hurter, who is the subject of the first chapter in the first volume of They Drew As They Pleased, taking our story full circle. The chapter about Joe Grant features countless treasures, including rare documents about Joe’s work on Disney’s World War II projects, and outstanding pieces of artwork from both his careers in the 1930s (Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, Dumbo, etc.) and 1990s (Beauty And The Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King). I knew from day one that Joe Grant would have to be included in this volume. It was a perfect way to come full circle, to tie things back to the first volume in the series.

The question became: who would be the other three artists? Joe had worked closely with both Mike Gabriel and Michael Giaimo, so both of them seemed to be an obvious choice. When I focused on their career and achievements, I realized that they had both been very influenced by some of Disney’s old timers: artists like Eric Larson and Mary Blair. Both of them were also great character designers and had worked on several projects that fascinated me, like the first (abandoned) version of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the Sweating Bullets version of Home On The Range, and The Snow Queen, which became Frozen. They were in.

That left only one spot. Since I had two “character designers,” I now needed a spectacular art director or someone who had established the mood of some Disney features the way Tyrus Wong had done for Bambi. Hans Bacher and his work on Mulan immediately came to mind.

Of course, this also meant that I could not include some artists that I loved like Paul Felix, Lorelay Bové, and many others. This really saddened me.

AV: The interviews gathered in your book bring something really fresh and dynamic. Can you tell us how you collected all these testimonies?

DG: In contrast to the previous volumes, three of the artists discussed in this sixth volume are alive. This gave me the opportunity to interview all three of them, extensively. The interview sessions would usually last for about 90 minutes, and I conducted between six and seven of them with each of the artists.

As to Joe Grant, his daughter was kind enough to give me access to her father’s archives, which contained some fascinating written documents and photographs, as well as countless reproductions of his drawings from the 1930s and 1990s.

Finally, in this sixth volume, one of the highlights was the fact that I had the opportunity to select artwork to illustrate the chapter about Mike Gabriel in the presence of Mike Gabriel himself. He was generous enough to (allow for) my taste, but I was privileged to get his guidance while making my selections.

AV: That period is also known for the arrival of digital technology in animation. What kind of impact did that have on concept art?

DG: In all honesty, not much. Most of the concept art I looked at for this volume had been created manually with a small amount created digitally. I would challenge you to find out which is which, though! The real impact of CG is found further down the line in the production process. It seems to me that pre-production remains true to its origins, even in the digital world.

AV: During your research on that period for the book, is there something you found that surprised even the expert that you are?

DG: The most exciting find must have been all the early character designs for Who Framed Roger Rabbit developed in the early 1980s by artist Michael Giaimo, which you will discover in the book for the very first time.

I also loved discovering the shelved short project I Am, which Hans Bacher had worked on for a short while and which meant so much to him. I am just fascinated by that artwork.

Another key discovery was the amount of work that Joe Grant and his colleague Dick Huemer had done on the projects that the Disney Studio was developing during World War II. I had no idea that there were so many and that their production history had been so complex. In fact, if you read the chapter about Joe Grant first, and then the endnotes from that chapter, you will realize that those are practically two full chapters about Joe in one volume.

AV: During that period, the personality of Don Hahn was essential. And he seems to have been also instrumental in your research. Can you tell me about your collaboration with him?

DG: As a producer, Don Hahn was at the very heart of Disney’s Renaissance, a.k.a. Disney’s New Golden Age. He is also passionate about Disney history and kind enough to like my work. While working on this sixth volume, I got the chance to get access to his archives that provided a wealth of background material which you see quoted throughout this last volume.

AV: You’re known for both TDATP and the Walt’s People series (which is often quoted in the book). Can you tell me how the two series complement each other?

DG: I would not have been able to write TDATP if it had not been for Walt’s People. While editing the hundreds of interviews that are included in the 24 first volumes of Walt’s People, I started learning more and more about Disney history and noticing the questions that I asked myself without finding answers. All of my books are attempts at answering those questions. Walt’s People provides part of the raw material. My art books are an attempt to put this wealth of material in context and to connect the dots.

AV: What will be your projects in the near future?

DG: Aside from the next volumes of Walt’s People (I am completing Volume 25 at the moment), I am also working on four heavily-illustrated, hard-cover monographs, which will be released by the non-profit Hyperion Historical Alliance Press.

The first one is titled The Origins Of Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventures and is already at the layout phase. I consider that volume as groundbreaking and I admit that I am very, very proud of its content. It sheds light on Disney artist Jake Day’s trip to Maine in 1938 to provide reference material for the artists who were working on Bambi; it tells the story of all the educational shorts that the Disney Studio was working on from 1943 until 1946; it focuses on the 1946 trip of cinematographers Albert and Elma Milotte to Alaska to film The Alaskan Eskimo and Seal Island; and it tells the story of all the abandoned True-Life Adventures that were also in development at the time. I have located the diaries of Lester Hall, Jake Day’s friend who went with him on the trip to Maine, as well as the lost diaries and autobiography of Al and Elma Milotte, plus countless letters, memos, photographs, etc. which help me tell those stories in great detail. Those are stories that have never been told before. I was blown away by what I discovered.

I am also now starting to focus on three other monographs: Walt Disney’s Adventures In Music, History And Nature (the second volume of the True-Life Adventures series); Meet Mickey Mouse! – Mickey Mouse On Stage And On Radio In The 1930s, in collaboration with my friend and fellow Disney historian Libby Spatz; and The Making Of Walt Disney’s Darby O’Gill And The Little People in collaboration with my friend and fellow Disney historian Jim Hollifield.

Although things are slowed down by the coronavirus crisis, this is fun!

Didier Ghez’s They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s New Golden Age is available to order from Amazon.com!

With very special thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney (Chronicle Books).