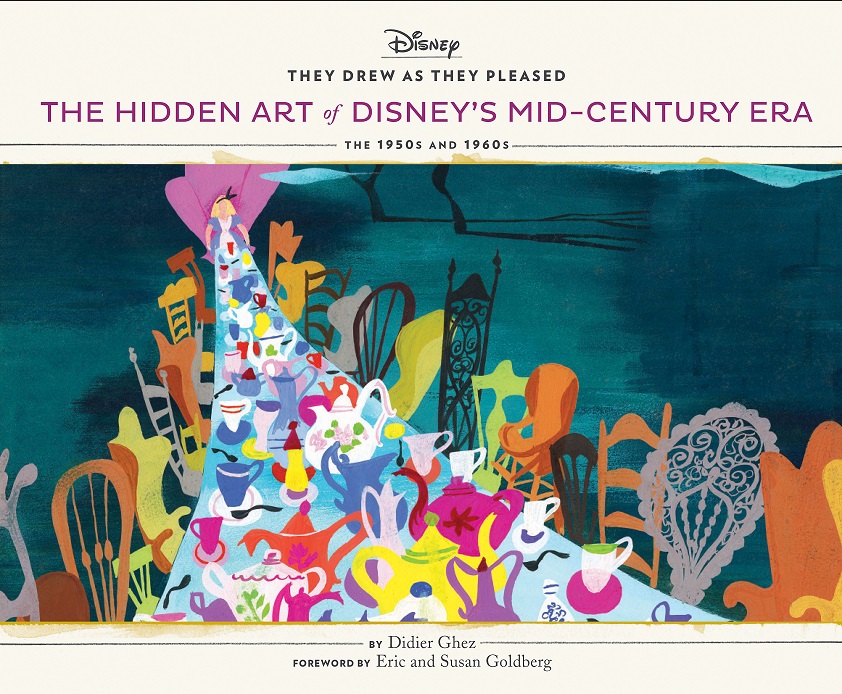

The fourth volume of the critically acclaimed and groundbreaking series of Disney art books, They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era, has just been released and it’s another success for famed Disney historian Didier Ghez, as he examines the fascinating history of the Walt Disney Animation Studios as never seen before.

The fourth volume of the critically acclaimed and groundbreaking series of Disney art books, They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era, has just been released and it’s another success for famed Disney historian Didier Ghez, as he examines the fascinating history of the Walt Disney Animation Studios as never seen before.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as the United States was bolstered by postwar optimism, the Walt Disney Studios embarked on a creative revolution brought on by the mid-century modern and graphic sensibilities of a new wave of artists. Disney fans will be familiar with two key developments during this time: Disney’s entry into the world of television, and the 1955 opening of Disneyland – an entirely new and exciting venture for the company. The story that is lesser known is the challenge for Walt Disney and his studio’s young artists to delight traditional Disney audiences while creatively embracing modernity.

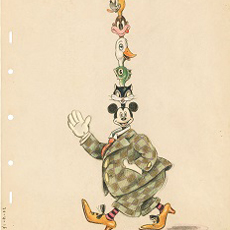

This volume explores the contributions of the unsung heroes who made that possible, with special emphasis on the art of Lee Blair, Mary Blair, Tom Oreb, John Dunn and Walt Peregoy, along with never-seen-before art, and unheard-of elements based on interviews with some of the artists themselves and correspondence from Mary Blair, to shed light on how the inspirations and limitations of these legendary artists helped shape the future of animation.

AnimatedViews: In your preface, you write that the artists of the 1950s broke the “Disney mold”. What was that “mold” like? And how was it broken, from an artistic standpoint?

DG: Before the 1950s, the stylistic approach favored by Walt Disney tended towards realism or at least a style that reminded one of some of the most famous European illustrators of the end of the XIXth century and early XXth century, like Arthur Rackham and Gustave Doré. Starting in the 1950s, the Disney studio and its artists started experimenting with a much more stylized approach.

The 1950s were dominated by the stylistic sensitivities of layout and background artists Eyvind Earle, Vic Haboush, Ray Aragon, Jacques Rupp, and Walt Peregoy, who were the new blood at the studio. Along with story artists Tom Oreb and John Dunn, they helped reshape the Disney style for a 1950s audience.

Earle had studied the works of Van Gogh, Cézanne, Rockwell Kent and Georgia O’Keefe before finding his own style at the age of twenty-one. Peregoy admired the Mexican muralists David Siquieros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. Fernand Léger, the French painter and sculptor, had been his teacher. Tom Oreb was influenced by Saul Steinberg, George Grosz, David Stone Martin, Ronald Searle and Pablo Picasso. Visions of “Modernism” coursed through their veins. The Disney studio at that time becomes much more adventurous in its artistic approach.

AV: You mention the importance of TV in the transformation of the Disney style, and also UPA. Can you tell me about the position of Disney in the entertainment industry at that time? From our present perspective, we tend to consider them as an all-time leader. But in the 1950s, because of the change of mentalities, they seem to be threatened by modernism and to have been forced to adapt if they didn’t want to look old-fashioned.

AV: You mention the importance of TV in the transformation of the Disney style, and also UPA. Can you tell me about the position of Disney in the entertainment industry at that time? From our present perspective, we tend to consider them as an all-time leader. But in the 1950s, because of the change of mentalities, they seem to be threatened by modernism and to have been forced to adapt if they didn’t want to look old-fashioned.

DG: As I write in the book:

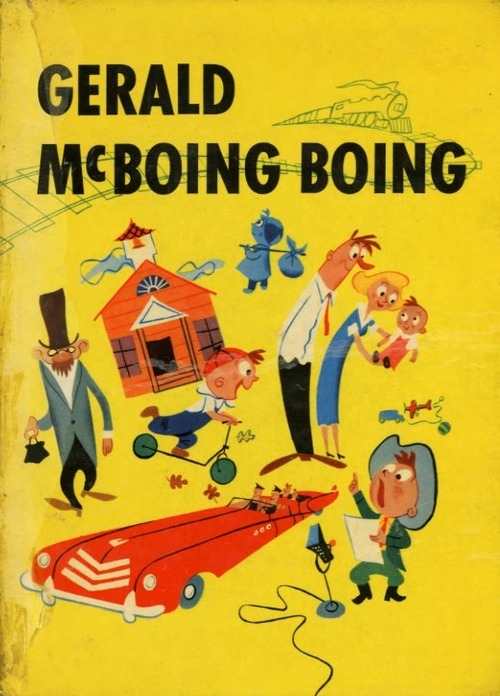

By the early 1950s, the Disney studio needed this creative shot in the arm. In the 1930s, Disney had won every single Academy Award for best animated short film. In the 1940s, Disney won only two, with MGM dominating the category. And in 1950, a new-comer got the Oscar for animated short: United Productions of America (UPA), with its visually inventive mini-masterpiece, Gerald McBoing-Boing.

Even outsiders were starting to notice. In the Time magazine issue dated February 5, 1951, one could read:

Walt Disney did not father the animated cartoon, but he has been its outstanding foster parent. Disney’s child, however, seemed no brighter or more grown-up in 1950’s Cinderella than in Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Last week a different kind of movie cartoon was being turned out by a one-time Disney hand named Stephen Bosustow and his bustling United Productions of America…

Gerald McBoing-Boing tells a funny story about a small boy whose efforts to talk produce only such sound effects as “Boing! Boing!” Everything about the film is simple but highly stylized: bold line drawings, understated motion, striking color and airy design in the spirit of modern poster art, caricatured movements and backgrounds as well as figures.

Vic Haboush was convinced that this specific article led to his being hired.

The reason I got hired [at Disney in 1952] was that there was a big article in Time magazine. It had Steve Bosustow’s picture… Steve Bosustow was the head of UPA. The title under the picture in Time was “The New Walt Disney.” He had a mustache like Walt’s. He even had Walt’s little smile on his face. When Walt saw that, he went crazy. He said, “We have got to get some new blood in here. We can’t allow these people to come in and try to take us out of the business.”

Along with the “new blood” and the UPA factor, the Disney style was pushed in new directions by Walt Disney’s decision to enter the new field of television. TV shows and TV commercials had to be produced at a lower cost. To meet those shrinking budgets, simplified animation was the obvious solution. It was less a question of switching to limited animation—the type that had been used by the Disney artists in the training shorts that they had produced for the Army and the Navy during World War II—and more a question of simplifying the characters and the backgrounds to make them quicker to animate without sacrificing quality.

AV: How would you introduce and describe the style of each of the five artists you treat in your book?

DG: First of all, I have to admit that I cheated a little bit in this volume. The whole book is supposed to be about artists who were active at the studio in the 1950s and 1960s. However, I decided to include Lee Blair, who was only working at Disney in the 1930s and 1940s. His approach (watercolor) and his style is much more classical than the style of the other artists in the book, and provides a good contrast for everything that follows. There was also no way to discuss Mary Blair’s stylistic evolution without first presenting artwork from her husband, Lee, since his style influenced her so much at the beginning of her career. And I just loved Lee Blair’s work too much not to feature him in the series. The storyboard drawings he created for “Aquarela do Brasil” (to name just one project) are simply to die for.

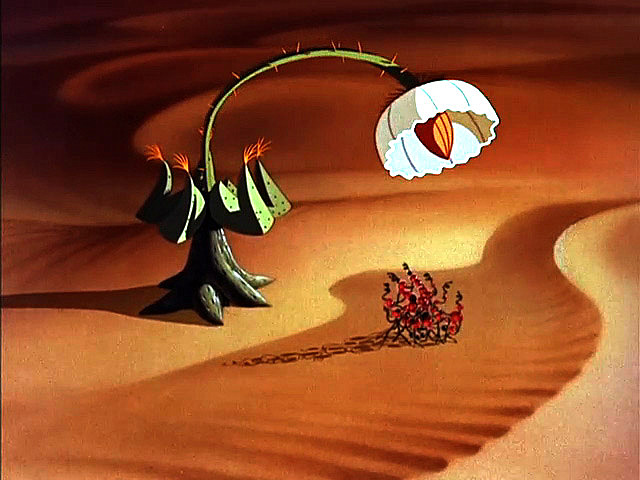

Then you have Mary Blair, who does not need to be introduced and whose naïve style and use of colors is always a pure delight. I tried to make sure to locate artwork that none of us had seen before in book form. I especially fell in love with some pieces showing Alice in the Tulgey Wood and meeting the Jabberwocky. And, of course, being married to a Brazilian, I can’t resist her work on the “Bahia” sequence in The Three Caballeros.

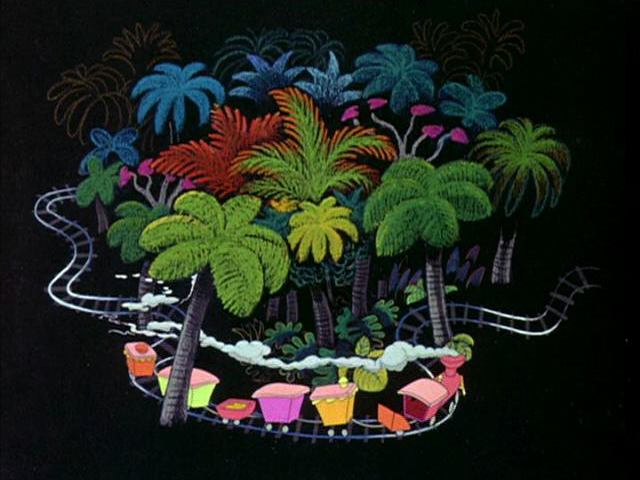

John Dunn was a much more complex artist to research. I knew practically nothing about his style before starting this project and there was extremely little information about him floating around. Little by little, I managed to piece together what his stylistic approach had been (both whimsical and modern) and I also realized that the best way to tell his story was through the science projects he had handled for Ward Kimball (Man In Space, Man And The Moon, Mars And Beyond, etc.). In the end, I was able to kill two birds with the same stone in that chapter: discussing John Dunn but also piecing together a detailed and precise account of the scientific projects from the 1950s which had always intrigued me.

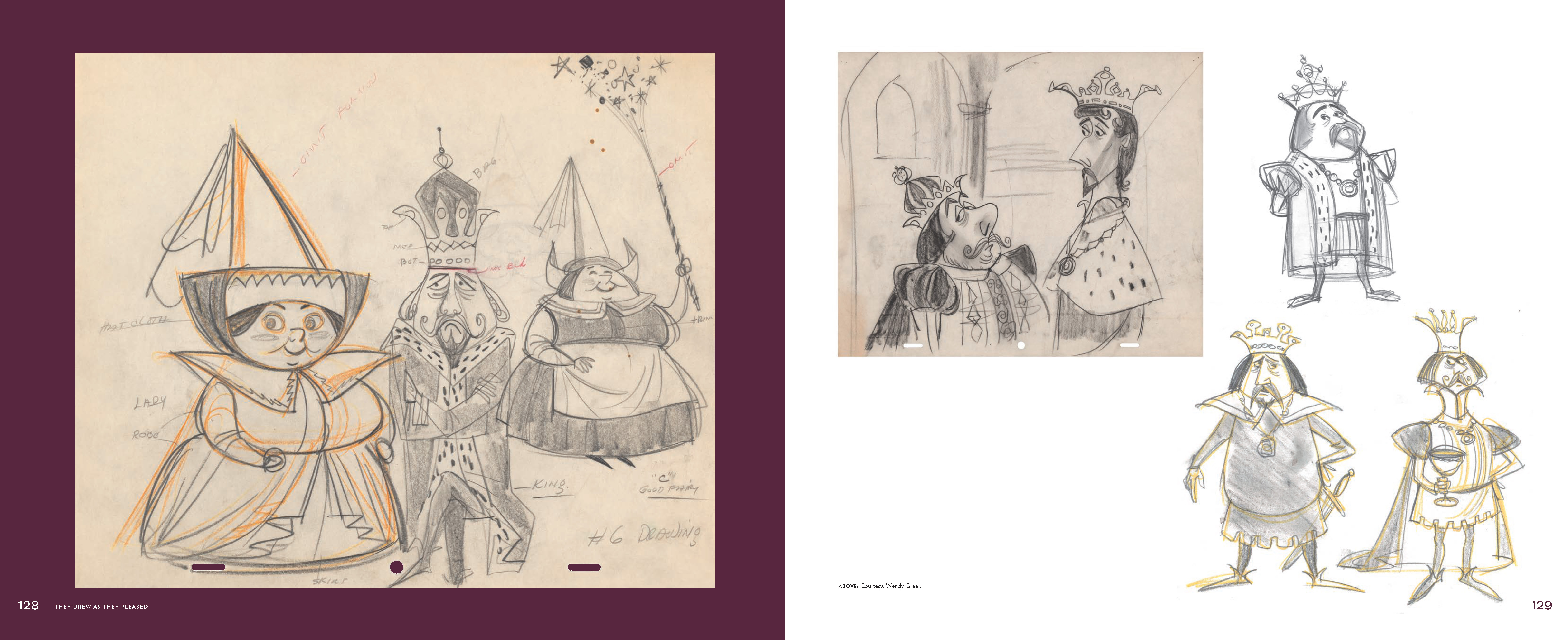

The chapter about Tom Oreb was even more exciting, from my standpoint, than the preceding three. First of all, while researching the career of Ken Anderson for the 5th volume of this series, I had stumbled upon a large amount of early Sleeping Beauty character designs by Oreb, which I was eager to share with the wider world. I also realized that if there was one artist whose stylized approach represented the 1950s more than anyone’s it was Oreb. Finally, it also gave me the chance to tell the story of the Disney commercials from the 1950s, a story that had seldom if ever been discussed and which would deserve a full book in itself.

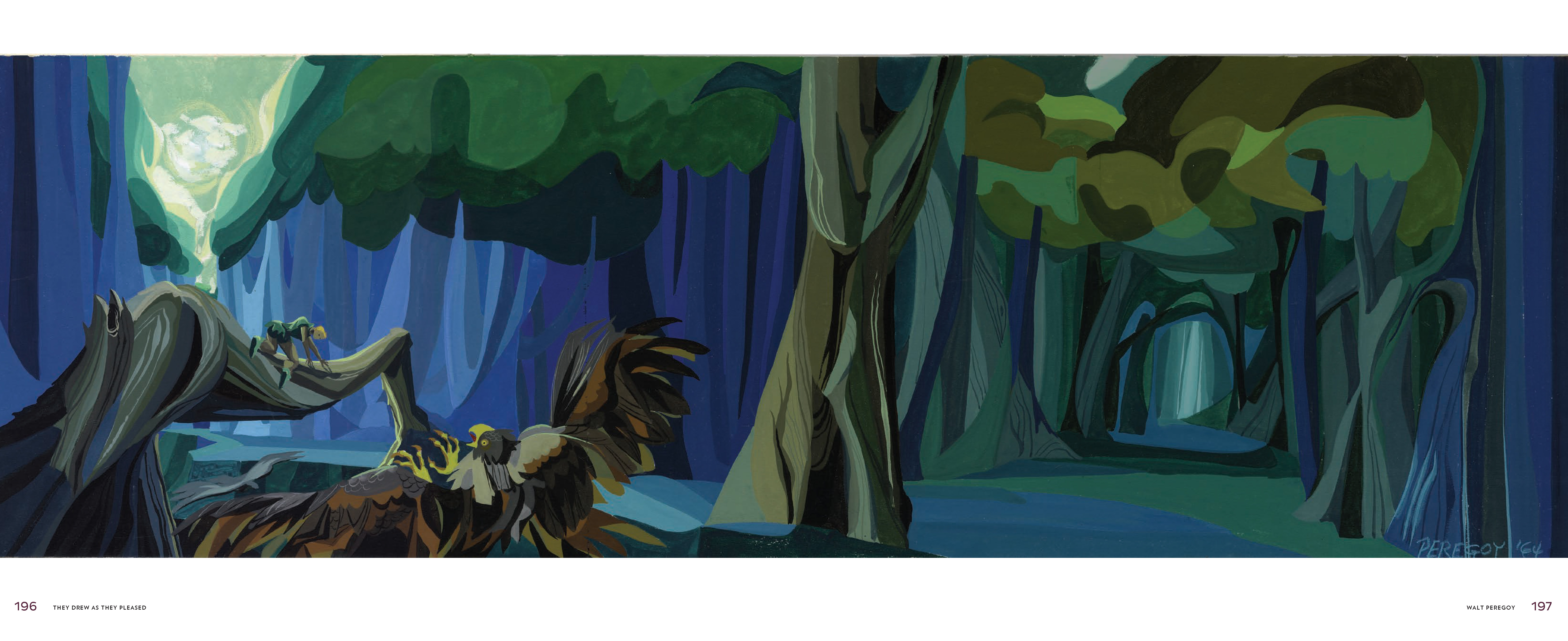

As to Walt Peregoy: this was probably the biggest revelation for me, while researching this book. Before working on this volume, I had been familiar with the personal drawings and paintings of Peregoy from the later part of his career, and I have to admit that I did not find them appealing. While researching his work for Disney, I was blown away by what I discovered: his mastery of style and colors in many ways goes even beyond that of Mary Blair’s. And his story, which was incredibly difficult to piece together (Walt was a notoriously difficult interviewee) is extremely rich and was very much worth telling.

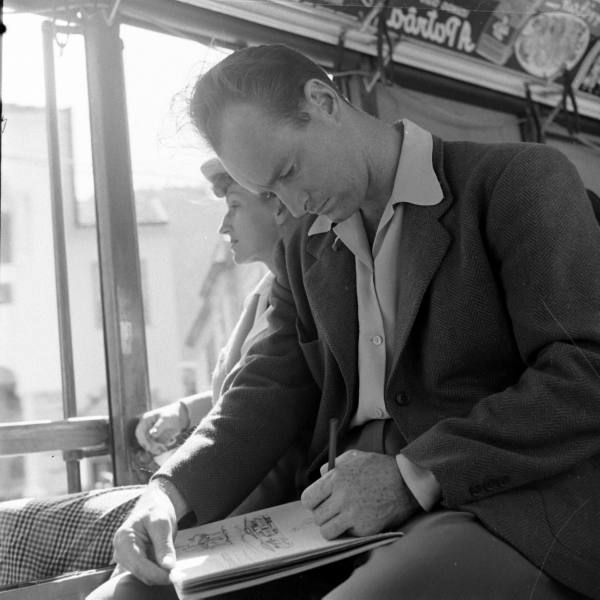

AV: Can you tell us about the different sources you appealed to? What’s the difference and the complementarity between the ARL and the Walt Disney Archives?

DG: I always try to tap into five sources of information and illustrations without which none of the books would be complete: the Walt Disney Archives, which preserve written documentation; the Animation Research Library, which preserves artwork; Disney’s Photo Library, which contains the photographic material; the family of the artists, who often have documents (and not just photographs) which are not preserved anywhere else; and private collections and archives. If you read the next answer, you will see that in quite a few cases, you have to link all of those dots to get the full story.

AV: A research work like yours must have its share of emotions. Could you evoke one or two exciting moments in the making of that book?

DG: Let me mention three of the most moving moments in the research process. When I was researching the work of John Dunn, I decided to interview producer Joe Hale, who had worked with Dunn in the 1950s. I was trying to get a sense of who John was as an artist and as a human being. What I did not expect was that Joe would mention that he had worked with John Dunn on an abandoned project for TV called Abdul Abulbul Amir. I knew that a file about that project existed at the Animation Research Library, but I had no idea that Dunn had been the artist who had created the artwork for it. Joe’s clue was critical and allowed me to include artwork from that project in the book.

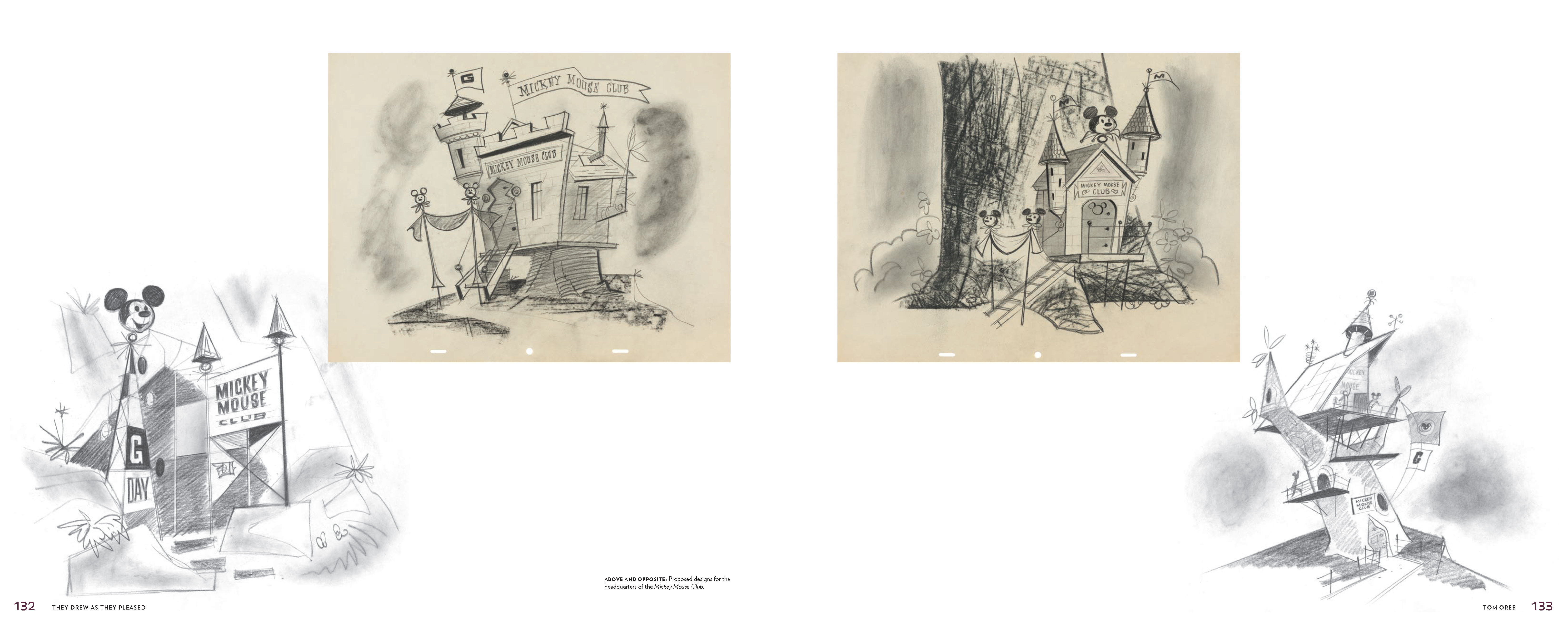

While researching the work of Tom Oreb at the Animation Research Library, Jackie Vazquez (my key point of contact at the ARL) and myself had the pleasure of stumbling upon some artwork created by Oreb for the clubhouse of the Mickey Mouse Club while looking for something totally unrelated. I still remember our delight and out excitement that day.

Finally, again while researching Tom Oreb, I stumbled upon a document at the Disney Archives which made clear that the last project that Oreb had worked on at the studio was a planned adaptation of The Baron Von Munchausen for television. Sadly, I also knew that no artwork from that project had survived at the Animation Research Library. I knew that the only option that might exist to find an example for Tom’s work would be if the storyboards he had created at the time had been photographed. I decided to find out. For this, I went to the Photo Library and started checking the negative lists one by one, week by week. I was about to give up, when I jumped on my chair: I had just found a negative description labelled “Baron Von Munchausen boards.” Thanks to this discovery you can get a sense in the book of what Oreb was trying to achieve.

(from They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era)

AV: This book is dedicated to Disney historian Joe Campana. Can you tell me how instrumental he was in your work?

DG: Joe was the (until now) unsung hero of this series. He is a dedicated Disney historian, who has spent most of his life studying Disney history but also tracking down the family of the Disney artists. Without him, I would not have been able to locate the diaries of Ferdinand Horvath for Volume 1, the families of Sylvia Holland and Retta Scott for Volume 2, the families of James Bodrero, Campbell Grant and Martin Provensen for Volume 3, or the family of John Dunn for Volume 4. Joe also spent months scanning various collections for these books, like the collections of Sylvia Holland, Campbell Grant, James Bodrero, John Dunn, Walt Peregoy, etc. I owe him more than to anyone else when it comes to this series. Without him, I would not have made half of my discoveries.

(from They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era)

AV: About the June Foray Award you received. It certainly is some acknowledgement for all the work you’ve already done, but what does this represent for your upcoming work?

DG: There was no honor that could have delighted me more that to receive the June Foray Award. I was stunned when I learned that I would be its recipient. If I needed more motivation to carry on researching and preserving Disney history in the future this would be the best motivator by far. Of course, even without having gotten the award, I would still be working hard on preserving more and more interviews for future volumes of Walt’s People, on writing the next volumes of They Drew As They Pleased and on trying to locate more lost autobiographies, like those of animator Frenchy de Tremaudan and story artist Leo Salkin. In other words: there are more treasures yet to come.

(from They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era)

AV: What about the future installments of the series?

DG: There are two more volumes of the They Drew As They Pleased series in the works before completing this ambitious venture. I am currently working on the layout of the 5th volume, which will discuss the 1970s and 1980s (The Aristocats, Robin Hood, The Rescuers, The Black Cauldron, etc.) and especially the careers of Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw, my two favorite Disney artists. And I am starting to write Volume 6 (the 1990s to the present) which will discuss the careers of Joe Grant, Mike Gabriel, Mike Giaimo and Hans Bacher. Exciting, to say the least!

Didier Ghez’s They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era is available to order from Amazon.com!

With very special thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney (Chronicle Books).