The late Golden Age ushered in an era of great productivity at the Walt Disney Studios. At a time when animation was becoming increasingly popular, it was also becoming more established. Walt Disney recognized that he had a talented story team and brilliant animators, but that in order to keep producing unique films, his studio needed to continue taking creative risks.

The late Golden Age ushered in an era of great productivity at the Walt Disney Studios. At a time when animation was becoming increasingly popular, it was also becoming more established. Walt Disney recognized that he had a talented story team and brilliant animators, but that in order to keep producing unique films, his studio needed to continue taking creative risks.

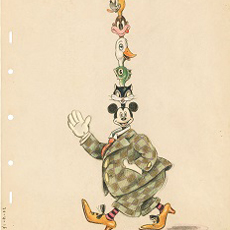

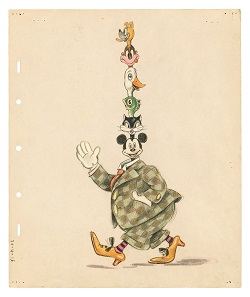

A visionary, Walt tackled this challenge by creating a wholly unique Character Model Department. This short-lived new department became Walt’s “think tank.” From experimenting with facial expressions and 3-D models, the artists in this division forged a new path.

In the third volume of the critically acclaimed and groundbreaking series They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Late Golden Age, famed Disney historian Didier Ghez examines this fascinating part of the history of the Walt Disney Studios as never seen before. The book profiles six remarkable artists from the Story Research and Character Model departments. Their astounding work, much of which is shown here for the first time, displays the free-form thinking that blossomed during the late Golden Age, and which gave rise to many of the classic characters we know and love.

We are more than happy to have Didier as our guest again to talk more deeply about his latest discoveries.

Animated Views: As John Canemaker puts it in a recent review, you’re a true Sherlock Holmes of Disney History. How did you get wind of the Story Research Department?

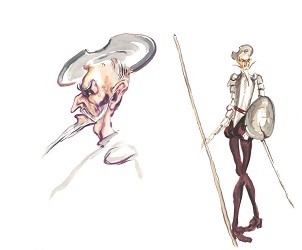

Didier Ghez: I had seen the name “Story Research Department” at the top of some internal memos from the 1930s during my research for They Drew As They Pleased – Volume 1 (The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Golden Age) and I knew that John Clarke Rose was the head of that department in the 1930s, but I was curious to find out if there was a relationship between that department and the Character Model Department or the regular Story Department. So, I asked animation historian Michael Barrier if he could share with me the interview he had conducted with John Rose (the only interview ever conducted with Rose). When I started reading that interview, I experienced a very positive shock: not only was Rose answering most of the questions I had about his department, he also mentioned something fascinating, the fact that he had hired in 1939 an Ecuadorian artist named Eduardo Solá Franco to work on an animated feature based on Don Quixote. My immediate reaction was, “Who the heck is Eduardo Solá Franco!?” By digging a little deeper, I realized that after his short stay at Disney (9 months) Eduardo Solá Franco had become a very famous painter in Ecuador. What I also discovered is that, while at the Studio he had created more than a thousand paintings for the Don Quixote project and that his story was a very dramatic one. And I was able to track down and translate all of his correspondence written at the time of his stay at the Studio. Reading it is like taking a time machine and being able to look over his shoulder while he worked on Don Quixote, Fantasia and Peter Pan. His artwork is extremely different from what we imagine as being the “Disney style” which makes it absolutely fascinating, from my standpoint.

AV: How different and complementary was that department to the original, more traditional “story department”?

DG: The story researchers (the members of the Story Research Department) were principally tasked with reading hundreds of stories, writing synopses, tracking down information regarding copyrights and securing appropriate rights to the most promising narrative material. They were not tasked with developing new stories, unlike the Story Department and the Character Model Department. Which in fact led to many misunderstandings when John Rose hired Solá Franco, something that he really was not supposed to do.

AV: You mention titles that were secured by John Clarke Rose. Do you know if some, like Robinson Crusoe and The Rubaiyat Of Omar Khayyam, went to the “concept” phase or did they just stay as “rights?”

DG: In the book I write, “In 1938, the year after the release of Snow White, Rose’s department secured, under the auspices of the Motion Picture Association of America, priority rights to no less than two dozen story titles which could be used for future features. Among them: Alice In Wonderland, Uncle Remus, Chanticleer, Cinderella, Don Quixote, Jack And The Beanstalk, King Arthur, Peter Pan, Wind In The Willows, Robinson Crusoe and even The Rubaiyat Of Omar Khayyam.” Of course Alice In Wonderland, Uncle Remus (Song Of The South), Cinderella, Jack And The Beanstalk (“Mickey And The Beanstalk” in Fun And Fancy Free), Peter Pan, Wind In The Willows (in The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad) were all eventually produced, and the Studio also tried many times to produce Chanticleer (in the 1930s, the 1960s and in the late 1970s) as well as Don Quixote (the different attempts are discussed in this third volume of the They Drew As They Pleased book series).

The Robinson Crusoe and The Rubaiyat Of Omar Khayyam ideas did not go very far. The Rubaiyat Of Omar Khayyam seems to not have progressed beyond a story synopsis created by the Story Research Department in the late 1930s, although the idea was still considered by the Studio as late as the early 1950s! When it comes to Robinson Crusoe, things went quite a little further. There was a suggested treatment written by story man Al Perkins in the late 1930s, as well as an attempt to create a remake of Mickey’s Man Friday (which itself is based on Robinson Crusoe). The model sheets developed for that marvelously elaborate short, which unfortunately did not make it to the screen, were developed by another artist featured in They Drew As They Pleased – The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Late Golden Age: the very talented member of the Character Model Department, Johnny Walbridge.

AV: Walt created the Character Model Department to have a team able to think “out of the box.” Why did Walt need to create other departments instead of asking different things to the artists he already had?

DG: Without being able to read Walt’s mind, the feeling I get is that Walt Disney saw his Story Department as very good when it came to developing shorts, but not so strong to develop full-length features. More importantly, he originally created the Character Model Department to develop memorable characters, but its leader, Joe Grant, pushed the department in other directions with Walt’s blessing and Walt was happy to use good ideas wherever they came from. The Character Model Department was full of great ideas, including one that saved the Studio: Dumbo.

AV: How would you summarize the progress brought by the CMD to the animation process?

DG: There were really two separate parts of the Character Model Department: one focused on developing model sheets and three-dimensional models of the characters, and one focused on developing new stories. Each had a different impact on the animated features. The first one helped the animators better visualize the characters in three dimensions and therefore portray them and animate them more realistically. The second one tried to introduce the studio to more elaborate stories, and also pushed the boundaries from an art direction standpoint: the artists of the CMD were much more aware of art history than their colleagues in the Story Department, much more aware of modernism and new art fashions and styles, and all this permeated their approach to story development, character design, and concept art styling. Fantasia is one of the projects that most benefited from these new stylistic experimentations.

AV: How do you explain the rivalry between the CMD and some of the animators like Ward Kimball?

DG: There were two key issues with the most “instinctive,” less intellectual animators like Kimball: the three-dimensional models of the characters were not always well-received by the animators. “[The animators] felt the models held them back, [and] that they were more or less restricted by that one form in them,” explained Joe Grant. “Some animators welcomed [them] as a tool, and other animators resented them as being restrictive, and declared [them] unnecessary. It was never [my] intention that the models should represent the only proportions that a character could assume. They were originally made for the assistants and inbetweeners more than the animators. [Bill] Tytla and [Milt] Kahl loved them. [Ward] Kimball and others resented them.”

Also, as Joe admitted, part of the problem came from himself and his team: “[Writer] Dick [Huemer], and myself, and Martin [Provensen], and [Jim] Bodrero: these people had read, they were intelligent, they knew music and literature, and they were good conversationalists. They were universal people, in their knowledge. I would admit that we were great snobs, that we looked upon these guys [the animators] as a hundred percent yokel. There was no changing them. We were roundly hated for it.”

AV: Would you introduce in a few words the different artists you mention in your book, and their style.

DG: There are six artists featured in this volume (which is 40 pages longer than the two previous ones): Eduardo Solá Franco, whom I discussed earlier; the wacky Johnny Walbridge, who designed some of the craziest characters for the clowns sequence in Dumbo and for the Tulgey Wood sequence in Alice In Wonderland (some of his creations for that sequence remind me of some of the Albert Hurter drawings featured in They Drew As They Pleased – Volume 1); Jack Miller, who was the ultimate character designer in charge of more than half of the model sheets generated by the CMD; Campbell Grant, whose recently-rediscovered letters to his fiancée take us to the heart of the CMD; James Bodrero, the “man of the world,” whose absolute versatility allowed him to handle any project with ease and who knew everyone that was anyone; and finally, my favorite, Martin Provensen, whose lithe, beautiful lines fascinate me. More than ninety percent of the art by those six artists that is included in this volume had never been seen in book form before.

AV: Your work is so amazing and such a pleasure to read that we can’t wait for the next one. What will it be about?

DG: Thanks for the kind words. They Drew As They Pleased – The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Mid-Century Era, the fourth volume in the series, will deal with the 1950s and 1960s. It will focus specifically on five artists: Lee Blair, Mary Blair, Tom Oreb, John Dunn, and Walt Peregoy. The difference in styles between those five artists is staggering: from the watercolors of Lee Blair to the very stylized designs of Tom Oreb and Walt Peregoy, the naïf approach of Mary Blair and the elaborate gag drawings of John Dunn. This is a volume that will take us into some almost unexplored areas of Disney history. I just saw the first layouts and I am extremely excited about them. But this is still for next year. In order to get there and beyond, as many of you as possible need to buy Volume 3, in order to help the series remain alive and reach its sixth instalment in 2020 if all goes as planned.

With very special thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney (Chronicle Books).