The Hunchback Of Notre Dame was certainly one of Disney’s most ambitious animated classics, challenging the limits of what complexity and strength the medium could bear.

The Hunchback Of Notre Dame was certainly one of Disney’s most ambitious animated classics, challenging the limits of what complexity and strength the medium could bear.

Also certainly Alan Menken’s masterwork, it was produced several times on stage, be it at Disney’s Hollywood Studios at Walt Disney World (1996-2002) or at Theater am Potsdamer Platz, Berlin (1999-2002).

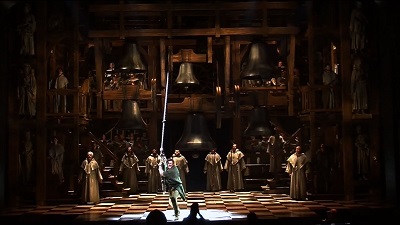

It was no sooner than 2014 that the piece went back to California and then to New York, premiering at La Jolla Playhouse on October 28 and then being transferred to the Paper Mill Playhouse on August 2015.

The studio recording of that latest version, the first ever of this acclaimed American stage score based on the Academy Award-nominated film, is now available and it shows the passion and ambition.

It features a 25-piece orchestra, a choir of 32, and some of Broadway’s most formidable talent: Michael Arden (Big River) as Quasimodo, Patrick Page (Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark) as Dom Claude Frollo, Ciara Renée (Pippin) as Esmeralda, Andrew Samonsky (The Mystery Of Edwin Drood) as Captain Phoebus de Martin, and Erik Liberman (Lovemusik) as Clopin Trouillefou. And it’s a huge success. Right after its release, the album was No. 1 on the Cast Albums chart dated Feb. 13, with 10,000 copies sold in the week ending Jan. 28, according to Nielsen Music. The set also made a striking debut at No. 17 on Top Album Sales and No. 47 on the overall Billboard 200 chart.

To talk about such a milestone in music theater history, we turned to long-time collaborators of Alan Menken, Music Supervisor Michael Kosarin and Orchestrator Michael Starobin.

![Hunchback_FeaturedShows_530x244_thumb[1]](http://animatedviews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Hunchback_FeaturedShows_530x244_thumb1.jpg)

Michael Kosarin was the original music director/incidental music arranger of the Broadway production of Disney’s Beauty And The Beast over twenty years ago, and has collaborated as composer Alan Menken’s music director since then. He has worked steadily on Broadway for over thirty years, on the original Broadway productions of Nine, Grand Hotel, Secret Garden, King David, Mayor, A Chorus Line, Triumph of Love, Little Shop Of Horrors, Can-Can (Encores!), Hunchback Of Notre Dame, The Little Mermaid, Leap Of Faith, Sister Act, Newsies, and Disney’s newest hit, Aladdin. His extensive film work includes the Disney animation films Pocahontas, Hercules and Home On The Range, as well as numerous live action films, including the more recent hits Enchanted, Tangled, and Captain America. He won an Emmy Award for outstanding music direction for his work on A Christmas Carol for NBC-TV – for which he also provided the underscore – and did music direction and underscore as well for ABC-TV’s Once Upon A Mattress and The Music Man (another Emmy nomination). He is currently music producer/arranger/conductor for ABC’s Galavant, currently producing its second season.

AnimatedViews: In every way, from the animated feature to the New York musical, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame seems to have taken a prominent place in music history, don’t you think?

AnimatedViews: In every way, from the animated feature to the New York musical, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame seems to have taken a prominent place in music history, don’t you think?

Michael Kosarin: I’ve always said and believed that, in every possible sense of the phrase, it is Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz’s masterwork. I think it is absolutely a classical masterwork. Such a mature work from both artists.

AV: You are yourself a prominent member of Alan Menken’s team. Can you tell me how it all started?

MK: It’s all due to my good friend and genius collaborator Danny Troob. At the time, I was living around the corner from where Danny was, here in New York. He’s a few years older than I am and had established himself, and he had asked me to assist him on a couple of things. We’ve become friends. At one point, when Beauty And The Beast (the stage show) came around, probably early 1993, David Friedman, who had very successfully collaborated with Alan as a music director for years, had told Alan that he wanted to venture off on his own and start his own career as a composer. So he told Alan that he wouldn’t be up to do Beauty with him. So, Danny suggested me to Alan. I went up to the place where Alan lived at the time in Katonah, New York, for an interview with him. It went extremely well. I think from the beginning, Alan saw that we have a lot of the same musical touchstones, very similar tastes in classical music, and in music in general. I think this is why we’ve got along so well professionally all of these years. And we saw that from the beginning. So, I was hired pretty much on the spot.

I was music director and arranger on Beauty And The Beast, and it wasn’t until a number of years later, maybe five or six, that Alan turned to me and said “look, this is going extremely well, you and I, and from now on, you’re my music director: absolutely everything that comes my way will automatically be yours. In exchange, I ask that anything you get that’s not me, that has a potential conflict, we discuss together” – and we have done so over the years. That was not the case when he got the film of Hunchback. I believe he started working early 1995 and I was at this time anyway too busy with all the international companies of Beauty And The Beast. I think I mounted 17 international companies for that show, so I was on the road pretty much 100% of the time!

AV: So, from your point of view at that time, how did you feel about Hunchback when it was first released on screen?

MK: I’ve been lucky enough to have been around New York in the 60’s and my parents took me to Bernstein’s young people concerts (one of my childhood dreams was conducting at what was in those days Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center, which is now David Geffen Hall, and I’m going to conduct there next week which is kind of a childhood dream. I’m doing a concert of one of the shows that I music directed in the 90s called The Secret Garden!) Now, I think like any musical theater fan, which I’ve been since early childhood, and any classical music fan, which I’ve also been since childhood, I just couldn’t believe my luck in getting to hear this. I had always been a fan of Alan’s music but then hearing this, the depth of the score, just starting with Bells Of Notre Dame and going in to the Latin music, and something like Out There which is I think one of the best ballads every written, and then the charm of A Guy Like You…it completely blew me away.

AV: The stylistic and emotional spectrum of that music is indeed incredible.

MK: You know, the tone of that piece is still evolving. It’s very interesting the journey that it’s had. It started out, as you know, as an animated film, but the subject matter is unbelievably unlikely as an animated film, such a very serious story. And if you really look at the Victor Hugo story, it ends horribly, with skeletons down in the crypt. It’s a very adult story about lust and passion. And that this ended up in essentially a children’s Disney animated film is sort of jaw-dropping. It’s almost like they said: “Hey, there’s this property called Sweeney Todd. Let’s make it into an animated musical for the kids!” Now, to speak to that genre, the animated film – they did write fun, joking, charming characters in the Gargoyles. They got A Guy Like You, performed by Jason Alexander and others who were able to bring the comedy so brilliantly. That helped with making the story work in the animated film.

Now, three years later, as you know, we went to Berlin and we went into a full-length musical piece. At that time, we were moving on to a different genre, obviously -the musical theater. We didn’t make that many changes to the tone. We made some changes we had to. It became a little bit more serious and a little bit darker, but not much. Esmeralda did die, but overall, we still had a very similar tone to the film, especially as the Gargoyles go: we still had A Guy Like You and very joking tone to keep it light.

Now fast forward to this latest iteration of the show, now we’ve really taken a big step toward getting back to the source material. The Gargoyles now have expanded. They’ve become the ensemble, with seven or eight singers, and they’re really more of Quasimodo’s inner voice. No more Guy Like You -I loved that song, but that’s a new version of the show. We’re not that kind of jovial, charming show anymore. It really kind of explores the depth of all of these passions. It’s very, very focused, and I have to say I think it works incredibly well. The score has also evolved so much over the years, including my own writing. It’s funny: I’m at the age now where I can look at what I did 20 or 25 years ago and say: “um, I might have approached that a little differently”. I think you’re just trying to show up a lot when you’re young; and I think, when maturity comes, this unison line is stronger than turning to fancy harmonies, high D is not really what’s appropriate here… so I changed the writing over the years, and it evolved greatly. I think people are really sitting up and rediscovering the score. Everybody I have ever played the Berlin recording for has gone absolutely mad for it, but now that we have this new New York (recording) that we made a few months ago, people are really discovering it. It is selling unbelievably well here. It’s very high on I-Tunes, and very soon went to #1 in Soundtracks, which is really quite incredible!

AV: When it was announced that the show would go from Berlin to the US, some feared it would become lighter. And it’s definitely the contrary. The show gained even more depth!

MK: Yes, it got darker and deeper. We really wanted to get truer to the original story because that’s a more interesting story. It’s okay that bad things happen and that people are driven by incredible lust and dark desires. It’s very interesting and I’m glad we did it. It’s a very mature show right now, and I have to say we get a lot of attention from venues that want to use that property. I don’t know what the next step is for us in particular but I think that 11 or 12, something like that, would be mounted in the next year or so.

AV: You did an incredible job, also, as a vocal arranger. So many different styles, from gypsy to plainchant, all concentrated in that magnificent Entr’Acte.

MK:Thank you! At some point when we were working at La Jolla, I was given the assignment of writing an entr’actebased on all of Alan’s themes, obviously. The assignment was interesting: to write an a capella entr’acte to show off this incredibly large and talented choir. I don’t remember if it was my idea or somebody else’s, but I think it was mine, to take the themes and write the lyrics in Latin, so that you’re not hearing any of the English lyrics during that moment. It was very difficult to make it land where we wanted to land with just choir, so at some point Michael Starobin did a bit of a Carmina Burana treatment to the orchestra. It complements what I did with the choir very, very well. It was a lot longer at one point and we knew the audience didn’t want to sit for something multi-minute, but I think it works well in the end. It was an unbelievable blast to write.

One of the great joys of working with Alan Menken over these many years is that he has such a command of so many different types of music that it enables me to write my arrangements in the whole of these types of music as well and keep my chops up and keep it interesting. For instance, for Galavant, I produced up to 65 songs over two years and each one, literally, was a different type of music, from doo-wop to tango to very specific music theater pieces. So, on Hunchback, I was able to write a kind of a gypsy scene in a European vein and other things in a more classical musical theater way, which is so much fun. These days, it’s so easy to investigate styles. You just have to go online and start looking and looking and looking. I’m still quite the student. I can spend the entire day researching and trying to get to the heart of what the sound is. And that’s what I’ve done. Hopefully, the result comes out and is truly evocative of all these styles.

AV: Do you have any specific example of a piece that was influential to you?

MK: Obviously, the mother of all choir arrangements is Carmina Burana. But I wouldn’t say that I really tried to specifically use anything that I heard in there. It’s really more like a chef, in a way, who might look 30 or 35 recipes to try to form in his mind an idea for a new recipe. You can’t point to that particular chicken dish or particular pasta. You’re just trying to synthesize all in your mind. Hopefully, the blender is your brain and you come with something new!

AV: What kind of musical references do you share with Alan Menken?

MK: It hard to pinpoint something in particular. Whenever I’m in a car with him driving and we’re listening to a classical station, he says “Oh my God, I love this”, and I say “I love this, too!” We share a sensibility. He loves French music, and I love Ravel, Debussy, Saint-Saëns. We also love romantic music, Brahms, Beethoven, Schumann. I think I tend toward a great love of jazz, I’m more of a jazzer in my background, but I don’t think he necessarily shares that. That’s how I brought some jazz elements to Aladdin, and I think that he appreciated it as any good musician.

AV: Speaking of the Aladdin musical, it’s been a great success over the world.

MK: Thankfully, yes. It was on Broadway two years ago, and by the end of next year, we’ll have six or seven running companies of the show. In addition to New York, we have Hamburg and Tokyo companies, that are doing incredibly well, and then we have Australia and West End happening this year, and a couple of tours happening next year. So, I’m travelling around supervising these companies.

AV: Were you involved in Alan Menken and Glenn Slater’s A Bronx Tale that has just opened at Paper Mill Playhouse?

MK: I saw Bronx Tale last night, and I spoke to Alan at the intermission and I said: “Alan, I tell you: I’m loving this but it is like an out-of-body experience to be sitting in an Alan Menken show that I didn’t work on.” Simply, there was no way for me to do it. There was a gentleman, Ron Melrose, attached to the project since conception, and he did a really superb job putting everything together and doing the arrangements and supervising it. So, it was fun to watch it but it was very strange at the same time!

AV: Indeed, right now you’re working on the live-action film of Beauty And The Beast. Can you tell us a little about it?

MK: I’ve been working on that for over a year now, I guess. All the principal photography has been completed. Right now, we’re heading toward recording the first few songs for the film. The way we’ve been working on the film is that we record the vocals first to synth mock-ups. From that, we can change things like tempos. Obviously, when you’re in the digital realm, you can do all those things. And then we record the orchestra after that. So, we’re heading to London next month and we’re gonna have a 92-piece orchestra. Danny Troob has got the chance to re-invent his orchestrations for the existing songs. As for me, some of the0 most challenging, fun and rewarding things I’ve done have been to arrange the underscore for the shows that I’ve done with Alan. I’ve approached music from #1 – the dramatic point of view and #2 – the musical point of view. That’s what appeals to me so much in underscores. How do we accomplish this or that, or get from point A to point B and sound like it’s always been that way, from the dramatic, emotional point of view? And so Alan let me do this for the first time on a film, helping him write some of his underscore. So, right now I’m tackling the songs and the interstitial music on the songs. And that’s what’s occupying most of my days right now!

Michael Starobin is a well-known orchestrator and arranger working on Broadway and in Hollywood. He has been the orchestrator for some of Broadway’s most innovative musicals such as Falsettos, Sunday In The Park With George, Assassins (2004 Tony Award for Best Orchestrations) and Next To Normal (2009 Tony Award for Best Orchestrations). He was the conductor and orchestrator for Disney’s animated film The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, orchestrated the songs for Tangled, and contributed orchestrations to the film versions of Chicago and Nine.

Michael Starobin is a well-known orchestrator and arranger working on Broadway and in Hollywood. He has been the orchestrator for some of Broadway’s most innovative musicals such as Falsettos, Sunday In The Park With George, Assassins (2004 Tony Award for Best Orchestrations) and Next To Normal (2009 Tony Award for Best Orchestrations). He was the conductor and orchestrator for Disney’s animated film The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, orchestrated the songs for Tangled, and contributed orchestrations to the film versions of Chicago and Nine.

AnimatedViews: Mr. Starobin, from the animated feature to the present Studio Cast version, you were the principal orchestrator of all the versions of Hunchback (the Walt Disney World adaptation excepted). Can you tell me about that journey of yours?

Michael Starobin: Well, it’s not really been a single journey for me. I have a full career with other projects. So, as opposed to a long journey, it’s more like coming upon a friend you haven’t seen for a couple of decades. In this case, it was coming upon and finding out he’s having a new marriage, that his life is all different. After doing a theatrical production in the 90’s with one team of directors and one concept, here’s a new production 20 years later with another director and another concept, which is the equivalent of having a new marriage and making new life decisions. That’s a better analogy for what it’s been.

AV: How did you approach the orchestration of the animated film?

MS: Because film is only being performed once, there is a budget to have a larger orchestra. I actually didn’t use as big an orchestra in Hunchback as many Hollywood orchestrators would use at the time. I did almost all the songs with a 65-piece orchestra, expanding it to 85 for only a few of the numbers. while most people were working with 100-piece orchestras in Hollywood at the time.

AV: And at the same time, the orchestra does sound big, even bigger than in other Hollywood productions!

MS: I just didn’t need more. Because I’ve been doing primarily theatrical orchestrations, and not film orchestrations. I come from a different place in writing for the orchestra and have different techniques of how I use the instruments and how much counterpoint I use. So, I actually approach what I do for an orchestra a little differently to a number of people in Hollywood.

AV: What kind of material did you receive from Alan Menken in order to elaborate your orchestrations?

MS: I receive usually a digital performer print-out. It was what Alan played at the piano for performing the songs. Back then, print-out was not cleaned up particularly because Michael Kosarin was not involved yet (he came on for Hercules, the very next film). So, Alan wrote a very detailed piano part, with most chordal accompaniment figures. Then we talked about the mood of the songs, about the dramatic content of the songs, the styles, the models he had in mind when he was writing the songs. Then, the counterpoints are something I added to the material.

AV: In the animated film, there’s the scope, and there’s also the tone, which is medieval. How did you treat this?

MS: The setting was medieval, and some of the writing that Alan was doing called for that fun harshness of things like shawms and crumhorns. So, a number like Topsy Turvy was quite a lot of fun to make, with all these noises that had intonations that were different from the well-tempered intonation that we had grown so accustomed to.

AV: Did you do some research in order to match the different styles used in that score?

MS: In theater, you’re rarely going to try and do a style exactly right. You’re really trying to do the songs the composer wrote and reflect the style that he’s touching upon. There’s not a reward for getting the style exactly right. There’s a reward for doing the songs exactly right as it should be for a musical, making them work in the flow of the show. Style is really a tool that’s used to help tell a story, but telling a story is always the most important element.

AV: How did you manage to adapt such a huge score to the theater?

MS: For both theatrical productions, the one in Berlin and the one recently in La Jolla and New Jersey, it really becomes a matter of numbers. Each time, you’re essentially cutting first down to 28 for Berlin and then to 14 for La Jolla, and each time, you’re just trying to cover as much of the content and style of the score in what you’re given. It’s basically reconceiving the counterpoint to the band you have. Cutting to 14 became so difficult that we ended up cutting the bass and emulating the bass on keyboard. We also lost things like the harp that became some synthesizer texture and we cut down to a string quartet. That radically changed the string writing. I have to completely re-conceive what was written for a string section to chamber music writing. That’s not really revealed on the recording where we went back up and used a large number of strings again, and there is no string emulation on the synthesizers.

AV: What kind of challenges did you face as an orchestrator of that latest version of Hunchback ?

MS: I think the song Out There was particularly difficult because it is so familiar to people and it is so based on large orchestral textures. I was happy with finding a solution that still made the song work. I simplified some of the string writing in just such a way the quartet could manage it and sing it. A part of it was not being slavishly faithful to what had been done before, but to rewrite lines to fit better to rewrite voicings for the brass, since there was only brass. We had a wonderful organ sample. You can’t hear a lot of it on the CD unfortunately, but in live performance that was useful to keep the scale and size of the band.

AV: Indeed, on a new venture like this one you have to find new solutions. But at the same time, you can see it as an opportunity.

MS: Yes. Take for instance Made Of Stone. I was never particularly pleased with the original orchestral, so I took another path without looking back and I think it came out much better this time. For Top Of The World it was interesting because Danny Troob had done the orchestration for me for Berlin, and now I had enough time to do a new orchestration. It’s an interesting way to compare the differences between Danny and me! Two different personalities.

AV: Someday is also very different from one version to the other -very spectacular in Berlin, much more gentle in the States.

MS: This was just a choice motivated by how it was staged. They each take place in the prison scene but it was staged very dramatically in the latest version where they’re both on their way to their death, and it becomes this choir prayer.

AV: I kind of noticed a nod to another Alan Menken musical of the 90’s –King David– in Flight To Egypt. Would you agree?

MS: I think in terms of Alan’s writing, absolutely. There’s some modal harmonies, and approaches that reflect what he did for King David. He used what you might call a minor key Jewish mode there, which relates to the early score composed for the movie Exodus, and also, for some of the music that was written for The Ten Commandments. He’s definitely evoking that which, in terms of a Hollywood context, completely evokes Old Testament. Not European Judaism, but a sense of Biblical Judaism.

AV: What are you up to, now?

MS: Presently, I’m about to work on Disney’s musical Freaky Friday, which has a score by Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey, which I’m co-orchestrating with Tom Kitt. Then I’m doing a show by John Kander and Greg Pierce called Kid Victory. And I’ve been contributing orchestrations to Galavant. It was a lot of fun. It was a good size orchestra and fun, silly material. There’s no attempt to make the songs fit to the flow of the cinematic story. The songs just jump out, so that makes lots of fun for the orchestrator to really go to town and have fun with the styles!

Our warmest thanks to Michael Kosarin, Michael Starobin and Rick Kunis