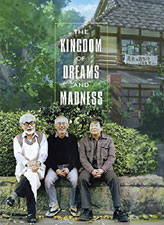

Ennet/Studio Ghibli (2013), Cinedigm (January 27, 2015), 1 Disc, 118 mins plus supplements, 16:9 ratio, 5.1 Dolby Digital, Rated PG, Retail: $29.95

Storyboard:

A year in the life of one of the world’s most revered animation studios is presented. During the production of The Wind Rises and The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya, the studio grapples with tight deadlines and the idiosyncrasies of its directors.

The Sweatbox Review:

Western audiences have had precious little opportunity to view documentaries on the venerable Studio Ghibli, Japan’s best known and most well regarded production house for quality animated features. Thanks to Disney and a few other distributors, we can at least have access to most of their films these days, but the discs that come with those films tend to avoid telling us what we really want to know, and instead focus on full-length storyboard presentations (which is cool enough), and hyping the American casts of the English language versions (which I am less thrilled about). Fortunately, a recent documentary has made its way to North America, a documentary that examines the production of two films, likely each the final one for two of Ghibli’s top directors, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

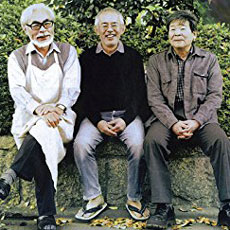

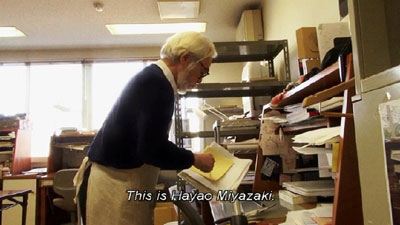

Director Mami Sunada was given what appears to be quite full access to Miyazaki in particular, following him around the studio and discussing his creative process and personal philosophies. Over the course of the film, then, the audience receives a full-on documentary about the making of The Wind Rises, providing further insight than what was glimpsed in Disney’s own quite good Blu-ray effort. Aside from Miyazaki, though, we meet producer Toshio Suzuki, as well as Ghibli’s legal man and several other staffers, each who give further insight into what it means to be a Ghibli employee. The gist, it seems, is that you have to really want to work there— for one must be willing to meet high standards and do his or her very best work, lest the perfectionist directors grow impatient with you. For those who are up to the challenge, the reward is in seeing great work be done. Those who cannot handle the stress leave to work somewhere less demanding.

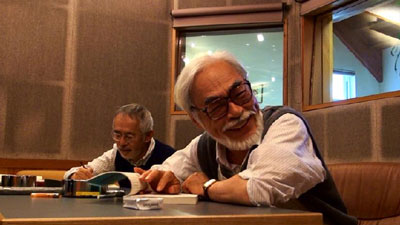

Many do stay, of course, enabling Studio Ghibli to put out great film after great film. Not all have been classics, of course, but overall Ghibli has an excellent track record. Most of that record is due to the efforts if its chief director, Miyazaki. It is fascinating to see him at the twilight of his career, discussing his personal philosophies with both Sunada and Suzuki. Miyazaki says he is getting tired, and we believe him. He has lost some of his optimism, and at times sounds like a grumpy old man; but just when you think you have him pegged as a grouch, he flashes a knowing grin, just to let you know that one should not take him too seriously. Still, it is undeniable that he has grown cynical about filmmaking and the world in general, lamenting as he does the growing selfishness of society, and a lack of incentive to produce good (never mind great) films. Suzuki, too, seems to think the world is passing the studio by— at least until seeing the reception for The Wind Rises, which got an admittedly mixed response, but was seen by many as an artistic triumph, and a commercial success.

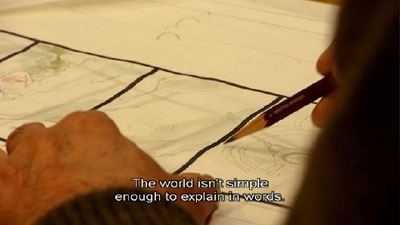

For those that revel in Miyazaki’s genius, they may be a little disappointed to see him struggle with certain drawings, or how he wrestles with how to end his film. It turns out he is human after all. He admits that he often doesn’t know how a story will end before going into film production (which explains Howl’s Moving Castle), or his disdain for explaining what happens in his films (which explains Porco Rosso). Of course, every genius is allowed his quirks, and certainly he usually has come through in the end, often surprising even his long-time colleague Suzuki, who has learned to trust the master.

The Wind Rises is a challenging film, and one sees even Miyazaki express difficulty in finding the right tone and message. Ultimately, he finds resonance with the story of his father, a man who got rich selling airplane parts during World War II. The film greatly reflects Miyazaki’s self-admitted conundrum of loving fighter planes but hating war. The story presents a tough balancing act, before settling into a story of how we are all swept up by the tides history. Amusingly, Miyazaki reflects on how he ever let Suzuki convince him to make the film.

Also shown in the documentary is the process of casting a veteran Ghibli staffer to voice the main character, after no professional actors were found to be suitable. We also see a conversation with Goro Miyazaki, who expresses his own doubts about following in his father’s footsteps. Additionally, after learning of Suzuki’s history working for a publisher, we see him deal with everyday business, from authorizing merchandise to writing copy for advertisements, and of course handling his “talent” in the studio. One of his most difficult cases is that of Takahata, a director that everyone respects for his ability, but a man who can be frustrating in how long he takes to get anything done. Kaguya has been in production for years, and Suzuki doubts it will ever be completed. He even tells a young producer to make a choice: either fire Takahata, or accept that the film will likely never be made. (The producer decided to stick with Takahata, as he could not envision allowing anyone else to take over the film. As we now know, the film was completed and was even nominated for an Oscar.)

Takahata is often discussed, but only shows up near the end. We are left to imagine that he is a little mysterious, but his impact on the studio has been profound. After all, it was he who “discovered” Miyazaki years ago, and mentored him during their television years. We do finally hear a few words from him, making the documentary somewhat complete. This is mostly about Miyazaki, though, and never have we had a better glimpse at the man.

Like many a Ghibli film, this documentary begins slowly and quietly, keeping the audience guessing whether the upcoming journey will be very exciting. Before long, though, the viewer is immersed in a tale that is as enlightening as it is captivating. This peek behind the veil shows the studio for what it is— the product of the people who run it and work for it. Though Miyazaki and Suzuki get the majority of coverage, we still get to see an ample amount of the rest of the studio working. Miyazaki thinks that anyone who wants to make movies is crazy, for it is hard and almost impossible work. Lucky, then, that the producers and directors of Studio Ghibli provide so much inspiration in addition to their own talents. The title of the documentary may bring up the notion of “dreams and madness,” but that is perhaps mainly in the eyes of the Studio Ghibli leaders. For Ghibli’s fans, we are left only with the impression of very human but gifted creators driven to share their talent and bare their souls for their art.

Is This Thing Loaded?

Ushiko Investigates (32:21) is ostensibly about the cat that prowls the grounds of Studio Ghibli, and at first I was worried that we were going to be subject to a half hour of watching the cat walk around the place and making wry comments, a cute joke that goes on far too long. There is a bit of that, but mostly this is a collection of scenes cut from the documentary, all valuable in their own way, but they did not contribute to the flow of the film. First up is a visit from Pixar and Disney animation head John Lasseter, and then footage of orchestral recording sessions with composer Joe Hisaishi, studio meetings, footage of what Ghibli’s legal man does, and more.

Digest Short Film (2:13) is simply a selection of brief scenes from the film, similar to the actual Trailer (1:32).

More From GKids offers trailers for A Letter To Momo, Patema Inverted, From Up On Poppy Hill, and Welcome To The Space Show.

Case Study:

The standard keepcase (not an eco one, for a change) has a matching non-embossed cover sleeve. This is no insert.

Ink And Paint:

The 16:9 image is as good as one can hope for standard definition, and in fact I was hardly able to lament the lack of a Blu-ray release. The picture is sharp enough, and colors are strong. A little banding can be spotted when blinds are shown, but otherwise the picture is stable and quite satisfactory.

Scratch Tracks:

The film is only available in its original Japanese, but that is how it should be. Though presented in 5.1, this is naturally a front-centered mix, with a little music found in the surrounds. Subtitles come in English only.

Final Cut:

This examination of Studio Ghibli in its final year with its two great directors is a great gift for fans. We see Miyazaki as both charming and driven, as he makes his final masterpiece. We see Suzuki attempt to wrangle his directors and producers. And we … don’t see too much of Takahata. But we do see how the studio operates, and gain a fuller appreciation for the talent that resides within its walls. There is a melancholic tone to the film at times, and one might be left with a tinge of sadness, realizing that Studio Ghibli will never be the same without Miyazaki and Takahata directing films. As we are told, though, there is nothing to worry about. There is only the passage of time, of things progressing and evolving as they must, and a new future to be decided by those that live in it.

| ||

|