As the Walt Disney Studio entered its first decade and embarked on some of the most ambitious animated films of the time, Disney hired a group of concept artists whose sole mission was to explore ideas and inspire their fellow animators. These early trailblazers pushed boundaries in art and design, inventing new characters, novel story ideas, and striking visual styles that were often ahead of their time.

As the Walt Disney Studio entered its first decade and embarked on some of the most ambitious animated films of the time, Disney hired a group of concept artists whose sole mission was to explore ideas and inspire their fellow animators. These early trailblazers pushed boundaries in art and design, inventing new characters, novel story ideas, and striking visual styles that were often ahead of their time.

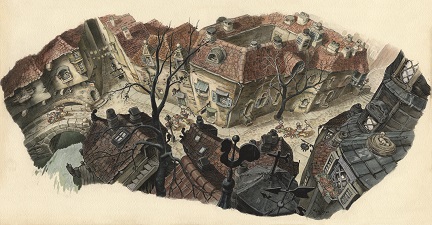

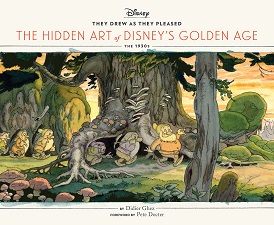

In his latest book They Drew As They Pleased, author and researcher Didier Ghez singles out four exemplary visionaries from this era: Albert Hurter, Ferdinand Horvath, Gustaf Tenggren and Bianca Majolie, the first woman hired in the Disney Story Department. Each of these artists brought their own personality and experience to the Disney Studio, and pushed forward many inspiring projects, most notably Disney’s first feature-length animated film, Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, as well as Pinocchio and Fantasia.

Much of the artwork in this book has not been seen by the general public since it was carefully catalogued and preserved decades ago in Disney’s Animation Research Library, the Walt Disney Archives, and private collections. Didier Ghez has brought to light numerous discoveries, from early Jiminy Cricket designs by Albert Hurter to documents by Gustaf Tenggren for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice With material culled from personal letters, journals and anecdotes from friends, family and coworkers, this unprecedented portrait of these artists comes to life, revealing how they helped shape the Walt Disney Studio, and how they continue to inspire us to this day.

Didier Ghez kindly talked to us about the first in what promises to be a revealing and fascinating series of books about Disney’s largely unexamined concept artists, with six volumes spanning the decades between the 1930s and 1990s.

AnimatedViews: They Drew as They Pleased seems particularly important to you. Can you explain why?

Didier Ghez: In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, most artists around the world were unemployed. One of the only places that was hiring artists at the time was the Disney Studio. This means that Walt Disney could hire the best among them. And the best among the best were tasked by Walt to “draw as they pleased” to inspire their colleagues, to stimulate their imagination and to take them in unexpected visual directions.

I realized many years ago that what really fascinates me when it comes to Disney are the artists and the whole creative process. The creative process is at its most intense when the story is being invented, and when the characters and locales are being designed. So the closer you get to the designers and the story artists – in other words the further you are from the finished shorts and features – the closer you are to the crazy ideas that are being invented to give birth to the animated cartoons we love.

It was therefore critically important for me to focus on the concept artists to understand this chaotic and fascinating creative process. And since they were some of the best artists hired by Walt, I also wanted to better understand their lives and careers.

One last reason why this series of books is so important for me, is that, since this is an official Disney project, I was able to share not only brand new information in the text but also hundreds of never-seen-before visual documents. Eighty per cent of the more than 400 visual documents displayed in the book are presented here for the first time. The same is true with most of the information in the text. There is barely any duplication with any books about Disney released in the past. I was clearly trying to break new ground and to move beyond John Canemaker’s spectacular book on the same subject, Before The Animation Begins.

AV: Your title also refers to another book in particular.

DG: A wonderful book about the artwork of Albert Hurter, Disney’s first “concept artist,” was released just after his death under the title He Drew As He Pleased. The title of my book is of course also an homage to Hurter’s book.

AV: Can you explain your particular interest in the first Golden Age of Disney?

DG: The answer to this question could almost be the subject of a whole book. But, in summary, it was the time when Mickey got his personality, when Donald Duck was created, when Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs came to life, when the Disney Studio created Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo, when it started working on Peter Pan, Alice In Wonderland and Lady And The Tramp. It was a time of excitement, discoveries and unbridled creativity. Work was intense but there was never a dull day, and Disney’s masterpieces were all born during that decade of the 1930s. How could one not be passionate about the creative history of those years?

AV: Would you explain what a concept artist is?

DG: The expression “concept artist” was invented by animation historians fairly recently and encompasses all of those artists who, at Disney, were tasked to inspire their colleagues visually. At the time they were sometimes called simply story artists or art directors, but they were always the most inventive artists and the ones that developed the most “blue sky” ideas. Not all of their ideas were “usable” but the majority of them are visually stunning and inspiring to this day.

AV: How did the studios work before such a job was “created?”

DG: When it came to creating stories, the studios before Disney operated in a very informal fashion, with the animators and the director coming up with gags and a rough story ideas. Walt Disney was the first producer to realize how important the story was and to establish a formal story department. Then, about a year after Albert Hurter was hired by the Studio in 1931, Walt realized that Albert’s outstanding ability lay in humorous exaggeration and the humanizing of inanimate objects. And so Walt started using him to inspire his colleagues visually and to enrich the design of his new cartoons.

In addition, in 1932 the budget for each Disney short had increased, thanks to a distribution deal with United Artists, which replaced Disney’s former distributor Columbia. Animation historian Michael Barrier theorizes that this may have been the factor that gave Walt the flexibility to free up Albert’s time to work solely on inspiration sketches and character design.

AV:You treat the art and life of Albert Hurter, Ferdinand Horvath, Gustaf Tenggren and Bianca Majolie. If you had just one word (or two) to express each one’s style…?

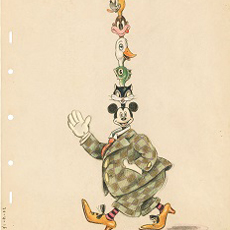

DG: Albert Hurter was the first of Disney’s concept artists and his grotesque doodles are often more fascinating than his more polished designs.

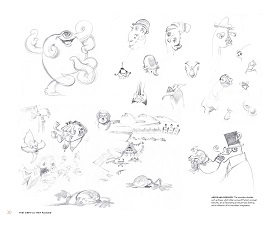

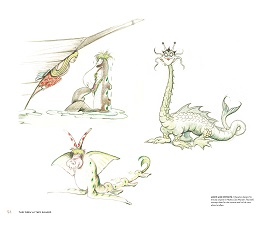

Ferdinand Horvath’s drawings are cartoony but also full of crazy details, and he was the kind of artist who could play endlessly with a concept and always remain creative. The sea serpent designs that he created for the abandoned short Mickey And The Sea Monster are a great example of this.

Gustaf Tenggren was first and foremost an extremely talented illustrator and all of his concept pieces look like elaborate paintings.

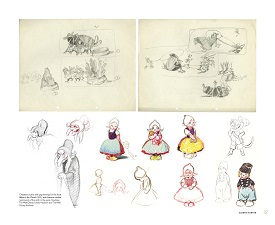

Bianca Majolie’s style often looks like Horvath’s with a feminine touch.

AV: It must have been amazing to get access to sources of that value!

DG: First of all, I was allowed to dig very deep into the collections of the Disney Archives and Disney’s Animation Research Library, which in itself was a dream come true. But above and beyond this, I also got access to the collections of the artists themselves: I unearthed a complete set of Ferdinand Horvath’s diaries, and the letters he wrote to his wife in 1933 when he was in Los Angeles and she was still in New York; I located, thanks to Tenggren expert Lars Emanuelsson, a rare interview with Tenggren in which he discusses for the first and only time his work at Disney; I got access to rare letters that described Albert Hurter’s last days and his last contributions to the Studio; and I also got to read and release the hilarious epistolary exchanges between Walt and Bianca Majolie before Bianca was hired by the Studio. In many ways, this was like building a time machine and my goal in the book is to take readers on board this time machine back to Disney’s Golden Age in order to look above the artists’ shoulders.

AV: You got access to Ferdinand Horvath’s journal. Can you tell me more about that episode of your journey?

DG: A whole book could be written about the research process that led to the writing of this first volume. The lucky breaks and stunning coincidences would be hard to believe even in a novel. Here are a few highlights.

A serious historian should not reinvent the wheel, so the first thing I did was to get access to Disney historian John Canemaker’s files, which are stored at New York University. I knew they would contain some great interviews with Disney concept artists and their families. Those interviews had been conducted by John when he was researching his book Before The Animation Begins. While checking the interview transcripts carefully, I stumbled upon a sentence that gave me a jolt: one of the interviewees was talking about the diaries of Ferdinand Horvath which had just been sold to a Los Angeles dealer a few months before the interview was conducted. Diaries, correspondence, memoirs and photographs are the treasures good historians are passionately seeking, which explains my excitement. That interview, however, had been conducted more than 20 years ago; and John Canemaker had clearly not located the diaries at the time of the interview. Was the lead worth following? Surely the trail would be freezing cold by now.

I would not respect myself as a historian, however, if I did not follow every trail. I did, and thanks to my good friend Joe Campana, I managed to locate the dealer. I left a message on his answering machine and did not hear back from him… until a week later. I was on a business trip in Mexico and the phone rang between two meetings. “I am the son of the dealer to whom you left a message last week.” “Is your father still alive?” “He is and he is with me right now.” “Does he still have the documents?” “He does and he would like to sell them.” I could not believe my ears. Not only did the dealer still have the diaries, he had also preserved a whole pile of letters, which I did not know existed. Part of the material was in Hungarian, part in German. All of it was utterly fascinating and helped me write a chapter about Horvath filled from start to finish with brand new information as shared by Horvath himself.

AV: A research is also a voyage of discovery. What did you discover that you didn’t expect?

DG: Part of the originality of They Drew As They Pleased is the fact that it relies so much on correspondence, diaries and interviews, which act as small time machines. Finding the only known interview with artist Gustaf Tenggren, thanks to Lars Emanuelsson, was therefore particularly exciting. But reading that interview, at first, was slightly frustrating: in it, Tenggren was discussing his work on one of the scenes of Fantasia, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Unfortunately, when I read that interview for the first time, I knew that no artwork by Tenggren from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice had even been located. A few weeks later, an animation art dealer from Los Angeles, knowing that I was on the West Coast, asked me if I wanted to check out a few Leica reels from Fantasia that he had just acquired. Leica reels are a form of storyboard on film that was popular in the late 1930s and in the 1940s. Among the reels was one which had been created with early story art from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, complete with four pieces that had been unmistakably painted by Tenggren! The timing of the find was astonishing.

But it is another piece of artwork by Tenggren that still makes me smile. One of the most beautiful and moving pieces of art included in the book is one of Geppetto lifting an apparently lifeless Pinocchio. Unfortunately that piece had never been seen in color and I had to accept the idea of including a black and white reproduction in the book. Two weeks after the book was sent to the printer, however, the color artwork was offered for sale for the first time ever by a famous auction house. My joy is still intact when I open the book and see this page in color instead of in black and white.

I could tell similar stories for almost all of the 350 never-seen-before illustrations that appear in the book and for each never-released-before story in the text, but this would prevent me from researching the second and third volumes in the series. I have a feeling that the treasure hunt will remain fascinating for a long while since there are still so many hidden Disney artists and so much hidden Disney art to re-discover.

AV: Bianca Majolie is at the origins of Elmer The Elephant, which is much praised by Frank & Ollie in Too Funny For Words for its pathos. Can you tell me more about what Bianca Majolie brought to the way Disney approached cartoons?

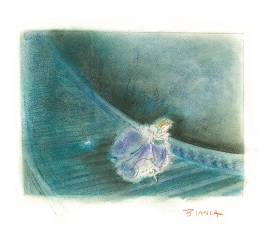

DG: This will sound a little bit vague, but Bianca introduced a woman’s sensitivity to the projects she tackled. The colors and motifs in her drawings are softer and more subtle than those of her male colleagues; there is more emotion, more tenderness, more lightness in all the stories she tackled. The best example being the tender Japanese Symphony drawings, which are shown in the book for the very first time.

AV: Can we consider Walt Disney as a pioneer in the way women were considered at that time in Hollywood?

DG: Not really. There were already some female script writers in the different studios and Walter Lantz, since about 1934, had a woman animator on his staff: Laverne Harding. But I believe that the Disney Studio was the first animation studio to hire women artists in the Story Department, first with Bianca Majolie in 1935 and then with Sylvia Holland, Ethel Kulsar, Retta Scott (who was first and foremost a story artist, as we will see in the second volume of They Drew As They Pleased) and, of course, Mary Blair.

AV:Your book treats art that was used in films that were ultimately produced and other that never got to the screen, following the path of John Canemaker’s famous book.

Why is it so important to treat films that never got finished? What can we learn from them?

DG: First of all, the artwork that was created for those abandoned projects is often as beautiful as the artwork created for the projects that actually made it to the screen. It would be extremely sad to neglect it and for readers never to enjoy it.

In addition, many of the Disney projects had their roots in concepts that were abandoned, so very often you cannot understand the genesis of produced projects without understanding the unmade projects.

And it is simply fun to re-discover those lost cartoons, as it is fun to discover artists and styles that we knew so little about, instead of exploring again and again the same aspects of Disney history. Don’t you think?

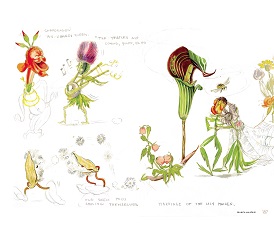

AV:A good example is the Ballet des Fleurs, which you mention several times in your book. Can you tell me more about that abandoned project?

DG: In 1936, Ferdinand Horvath, Gustaf Tenggren and Bianca Majolie were working together on the concept of a very elaborate Silly Symphony that would have revolved around a beautiful ballet featuring flowers as star dancers. The variety and whimsy of the hundreds of concepts of flower dancers developed by the three artists is stunning. While the project was eventually abandoned, a lot of the ideas developed were eventually integrated in some sections of The Nutcracker Suite in Fantasia, several years later.

AV: What can we hope for in Volume 2?

DG: Volume 2 will be subtitled The Hidden Art Of Disney’s “Musical Years” and will focus on five artists who were particularly active in the 1940s: Walt Scott, Kay Nielsen, Sylvia Holland, Retta Scott and David Hall. As mentioned, in Volume 1 about eighty per cent of the documents shared in the book had never been seen before. In volume 2, practically none of the documents included have ever been seen before. And while in the first volume, a large part of the visual documents come from Disney’s Animation Research Library, in volume 2 more than half of the documents will come from private collections, including the collections of the families of Sylvia Holland and Retta Scott.

Finally, I am as excited about volume 2 as I am about volume 1. It will showcase the careers of two extremely versatile women, Sylvia Holland and Retta Scott; it will explore some abandoned Disney projects that we had no idea existed; and it will display some of the most spectacular artwork by my favorite Disney concept artist, David Hall, including a masterpiece from Peter Pan, which I hope will be used for the cover.

Our deepest thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney at Chronicle Books