We all remember Duet, the first production of the joint venture of Glen Keane Productions and Google.

We all remember Duet, the first production of the joint venture of Glen Keane Productions and Google.

As he was working on projects at Google last year, Glen met Benjamin Millepied, the new Director of Dance for the Paris Opera. Following that meeting, Glen was personally invited by Benjamin Millepied to join a distinguished list of artists and filmmakers to help launch 3rd Stage. As Stéphane Lissner, Director of the Paris Opera, describes it, the 3rd Stage is “an autonomous venue for digital creation to complement the Palais Garnier and the Opéra Bastille. The aim of this digital 3rd Stage is to commission new works from artists through original pieces offering an original perspective on the world of opera, music, dance, our cultural heritage, the architecture of our two theatres and the skilled professionals working at the Paris Opera”.

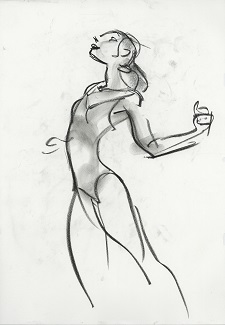

Nephtali, which refers to Jacob’s blessings and Psalm 42, was born from the comparison between the grace of a dancer and that of a deer. In a choreography that Glen created with dancer Marion Barbeau, he depicts the journey of a soul that is drawn towards a higher power, fights a struggle, and is eventually liberated. By using both film and drawing, Glen and Marion manage to overcome the constraints of gravity and attain the freedom towards which a dancer’s body and spirit always aspire.

But that’s only part of the richness of Nephtali. Glen Keane kindly told us more about that unique project.

AnimatedViews: Coming just after Duet, Nephtali is another step in your new and most promising career as an independent animator. How do you feel about it?

Glen Keane: As I left Disney, I didn’t know how I was going to express myself as an animator. I just knew that I needed something maybe deeper, something less commercial, more artistic, but I didn’t know how that would happen. And the way it’s been happening for me is new platforms opening up that invited me to be myself. Google asking me to come into their world and be me. They didn’t care to tell me what to do. They just wanted me to push myself creatively. They would benefit by me really expressing myself. And that was very much the same invitation that I got from Benjamin Millepied: “Come here to our world and be you, bring something of yourself.” I was a little nervous to take something so personal as my own spiritual life, my own faith and my own love for Psalm 42, and put that out there and ask a ballerina (whom I had never really talked to before until that day) to interpret something very personal for me. And she did. She could embrace that idea.

Now I feel like I’m just beginning to really enjoy that new artistic growth that’s happening in my life. I look around and I see different things I’m interested in doing. They all share a similar kind of a flavor. There’s something happening for me as an artist and I need that kind of freedom to discover it— that freedom that Benjamin gave me.

AV: Indeed, Nephtali is really one-of-a-kind. How would you define it?

GK: For me, Nephtali is more of a visual poem, just like Duet was; a visual poem based on a poem that is Psalm 42. For me, animation is more of a poetic way of communicating emotion without having to follow the traditional Hollywood story.

AV: In that perspective, how did you build your story?

GK: For me, that short, little poem of Nephtali has something of a symphony, in three movements.

Psalm 42 begins with “As the deer pants for streams of water, /so my soul pants for you, my God.” So, for the first movement, I was looking for a word for the dancer, Marion Barbeau, to express a yearning, something that comes from deep down inside and drives you, an elemental force inside of us that’s really a spiritual calling. So, the first word I found was “longing”.

The second word was “conflict”. Psalm 42 says : Deep calls to deep / in the roar of your waterfalls;/ all your waves and breakers / have swept over me.” So, there’s actually this struggle.

And the third one was “freedom”. When Jacob, in the Bible, was blessing his twelve sons and came to Nephtali, he said: “Nephtali is a doe set free, that bears beautiful fawns.” Between Psalm 42 and that blessing on Nephtali, it just all came together for me and I wanted to animate that.

Then, on my walk over from my apartment to the Opera Garnier, I was thinking: “What am I going to do?” I had never done choreography before. And then I remembered I had watched Benjamin Millepied and learned how he was doing choreography very intuitively, working with the dancer. So, I tried to do what Benjamin did. I had also heard that, within a ballerina, there may be up to 60 choreographies in her muscle memory at any time. Maybe Marion had not as many because she’s younger but a fully mature dancer might have up to 60. So, maybe I should just have her dance to one of those and I’d just draw the movement.

And, as I was thinking that, I could hear Ollie Johnston, who was my mentor, his words: “Don’t draw what the character’s doing. Draw with the character’s thinking.” So, I had to give Marion what the intent is, what the motivation is. This had to be really motivated by a desire, something inside, something I could translate and enhance with animation, and take it to a higher plane. So, that’s what I talked with her about, and I wrote those sections of Psalm 42 and Jacob’s blessing in French for her, to be able to think about it and interpret those words into movements. I also did a lot of thumbnail sketches for her, showing her the ideas that I wanted to see. Together, we really worked that out but I was very much dependant on her very sensitive interpretation of what I was communicating to her.

AV: Why is Psalm 42 so important to you?

GK: Well, as it starts with “As the deer pants for streams of water,/so my soul pants for you, my God.“, I experienced in my own life, spiritually, that kind of a longing, the exact same kind of feeling. When I was 20 years old, I was at Disney. I had just started a few months there and I experienced that kind of real, strong desire to know my Creator. But I had no idea how that could be. At the same time, I was learning from Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, and Eric Larson, all these wonderful principles of Disney animation. But, even greater than this incredible discovery of animation that was happening for me as a young artist, was a deeper longing, a spiritual one. At one point, early on in my career, I had thought that I wanted to become a pastor, to leave animation. Because I was reading the Bible and I found that it was so incredibly true and revealing of human nature and divine nature that I was fascinated with it and I wanted to describe that, explain that, talk to others about that. And I went to talk to my pastor about that possibility and he said: “Maybe God has you there for a purpose, and you should really stay there, where He planted you.” And I did.

And then throughout my career, there’s been opportunities to express myself, express that deep spiritual longing. Like for Ariel, wanting to be part of a world that is totally impossible for her, as she sings Part of Your World. That’s really a very spiritual allegory in a way. Longing to be part of something up there when you can’t even breathe that air. But it wasn’t going to stop her. I love characters who believe the impossible is possible. As for the Beast, the whole transformation of him was very close to a feeling of the transformation we can read in Corinthians 5:17: “if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; old things have passed away; behold, all things have become new.” I was animating that kind of feeling. Pocahontas’ hair, the way it moved was a way for me to describe her spirit. Because I first animated scenes where she was just standing there and her hair was hanging down still, it didn’t communicate who she is. As soon as I put in this movement, it was like, “That’s it! There it is!” It was the music of her soul that was in her hair. That way, my spiritual life and animation have been flying together all my entire career, and they will continue to do that, I hope.

AV: How did you come to this idea of associating a dancer and a deer?

GK: For many years now, I’ve been noticing the power of a deer leaping over stone walls and somewhere in my mind, I’m impressed with the creation and ballet-like movement of that deer. And when I see a ballerina with her beautiful, long neck and her very elegant, noble pose, I compare that to a deer. When I’m drawing dancers, I’m drawing deers. These ideas reverberate between one another. It’s almost like a chord. You hit a few notes on the piano and create a resonance between those two notes that work so well together. That’s what’s happening for me these days as I think about these ideas.

AV: Animation and choreography can collaborate because they have a lot in common. What’s your point about that aspect?

GK: One of the wonderful discoveries I had at Disney came to me by Ollie Johnston. He would say to me: “Don’t think in terms of all of the drawings that you are doing. There’s 24 per second. But it’s really pictures that you are leaving in the audience’s mind. The pictures that they remember are ‘Golden Poses’. You need to think in terms of just very few Golden Poses that will tell the story. There’s movement within and between those poses, but it is the power of a Golden Pose that really impresses upon the audience the emotion that you’re trying to communicate.”

One of the first scenes I animated was Penny in The Rescuers. I had so many drawings and poses. Ollie took the scene and pulled out, of maybe 60 different poses, two drawings. He said: “These are your Golden Poses. You don’t need more than that. The more you put in there the more confusing.” A master would be able to work within these poses and make them live.

The Golden Poses are powerful silhouettes, attitude that convey meaning. As I started to study ballet, I realized that’s exactly what they’re doing. I mean, they’re constantly moving, but they hit these Golden Poses as the ballerina leaps in the air and freezes for a moment like she’s flying in space with this beautiful, elegant attitude, with the knee angled, and one straight leg, and with the arms in diamond shape on top. That’s just this beautiful pose that happens to be spinning in movement, but it’s a Golden Pose. So, I realized, just like in animation, there’s just very few poses, but they’re very powerful in the way they’re communicating. In talking with Marion Barbeau, I was thinking: how can we really sell this idea of poses? So, I would work with her on those poses, on how to strengthen them. That’s where I spent most of my time. I also talked about Golden Poses from the very beginning with live-action director Benoît Philippon. Originally, our intent was, as Marion would hit the Golden Pose, we would freeze that in time and I would animate her moving in space with the camera moving around. But I ended up not doing that, because I didn’t feel like I had to stop her entirely to benefit that Golden Pose. I preferred instead to let the narrative take over.

AV: Recently, you experimented animating in space using the Tilt Brush. Seeing you animate that way looks like a kind of choreography, in its own way.

GK: You know, it’s funny. When I was at the Opera Garnier drawing dancers, I had my sketchbook and I was drawing as rapidly as I could, and I found the dancers to be very much like animators. They just drew with their body. There was this one male dancer who was leaping towards me and I sketched as quickly as I could in perspective that line of action from his head to his toe, but as he was moving towards me, you couldn’t see him. He was hidden in the perspective of the drawing. I was a little frustrated because I knew what was happening in his whole spinal column and this beautiful curve that must have been seen from profile.

After I left Paris the next day, I flew up to Google and put on this virtual reality headset to work with Tilt Brush. The first thing that came to my mind was that last sketch that I had done in Paris. Now I could actually express this movement and that line of action going deep into space. So, I drew that line of action from the dancer’s head all the way to his toes, but I just drew it in space. Then I stepped around on the side, and suddenly the line that I drew turned in perfect perspective and then I could draw the dancer in profile. I realized this was the fulfilment of the way I think about animation. It was very much a sculptural drawing. As I moved around the figure, I realized how much sculpting there is in this process of drawing.

I feel really connected and very close to Rodin. When I was in Paris, our apartment was not far from the Musée Rodin. When I’d go see his sculpture, I’d love to go in and look at his drawings; because these drawings are like liquid. They flow. There’s almost a breeze that blows through those drawings. They’re fluid and rhythmic, and they’re the key to understanding his sculptures; because those were the rhythms, the melodies that were in his mind as he was sculpting. And when I go somewhere and find his sculptures, I have to just draw them. I feel a real attraction to his work, a fluidity that wants to animate, and yet it’s solid, and weighty, muscular, strong, dynamic. These are the things that I’m trying to communicate in my animation, and in my choreography. He’s frozen in time, but I don’t have to be. I can actually sculpt in time now…

AV: What do you think could be the implications of such technology on storytelling?

GK:With Duet, your phone transformed into a virtual reality device, and you could watch that animation moving in three dimensions everywhere you turned. Instead of seeing it, you’re experiencing it. It’s a different way of describing it. You don’t just watch it like a movie anymore. Animation moving in that direction, storytelling really involves the audience in a deeper way. Because as you would watch Duet, you are making an investment. You are choosing where you want to go.

So, certainly, where I would love to see Virtual Reality go is to be able to animate in space. I am drawing one figure. But in my mind, I’m imagining a whole series of those figures moving in space. I did a lot of drawings of dancers with virtual reality, and I would love to see them dance and turn around them. As you would put your goggles on, there’s this living animated sculpted figure dancing and moving in that virtual space that you’re standing in. And what’s amazing is when you take those goggles off and you look at that same space, you realize that that figure is still there. I just can’t see it, but I know it’s there. You put on the goggles and suddenly there it is! It’s almost like The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe. You step through this magic wardrobe and there’s this other world.

How is that going to be interpreted in the future of storytelling? Right now, this is the most exciting era in animation. Many people feel like they’re missing the Golden Age of animation with Pinocchio and Snow White, or the second Golden Age with Beauty And The Beast and Little Mermaid. Now, it’s just a continuation of what was already invented and we don’t get to do that. Right now, there is a whole new era happening. It’s not formed yet. It takes a lot of experimenting and courage and craft, like the idea of drawing with Tilt Brush. I can do something relatively appealing, and I can draw relatively well, but I know I’m just testing this craft. And it’s going to take time and investment to let artists really learn that craft and tell that story. What Walt Disney did in order to do Snow White is that he personally would drive his artists to art school at night to teach them figure drawing. They could grow in their skills of action analysis. He turned his studio into school to do Snow White. I feel like that’s what has to happen today. There needs to be the development of that craft and to give people time to learn that, this new virtual world, platforms that could be actually in space around you. You don’t have to be in a movie theater. I’m very interested in that.

I remember Ollie saying to me: “Glen, someday you’re going to do greater things than us.” And at the time, I wished he’d never said that. How would I ever do greater than Pinocchio? And I realized – I can’t! You’ll never re-do a better Pinocchio. Then I realized he was not talking about greater in terms of quality. He was talking greater in terms of application and influence. That, to me, applied for so many new mediums. New applications, new fields, new platforms like VR, like ballet, and other ideas. We are just beginning to scratch the surface! I don’t think drawing is ever going to go away. We’ll just find new ways of it becoming important for animators. For me, drawing certainly became now, like you noticed, choreography. I mean, I thought like I was kind of dancing, in a way. Strangely, I was drawing everything full size. I didn’t know why, but I had to be drawing Beast seven feet tall. I had to stand on my toes to draw his horns. I could make him so much smaller, which would have been easier. But I didn’t want to because he really is that size in my mind.

AV: Now, as a dancer yourself, you seem to embody the rhythm of your drawings.

GK: Yes. My body is a reflection of the line that I’m drawing. I’ve always felt that. I’ve always experienced that physically inside of my muscles. I feel the pose. I remember the first time I worked in computer animation. I took the model of Rapunzel and started to manipulate her figure on the computer. I had to work so hard to get that figure turning in position just the right way and I found that my neck was hurting, my back was hurting. I was reflecting all of these awkward CG poses I was trying to put her in, because I didn’t know how to do it very well. I didn’t know how to do it as well as many of the other animators at Disney that were used to that technology, and I realized how invested I am physically in that whole experience. It was actually a painful experience for me. Because in drawing, I can feel that pose. And it doesn’t have to be a big, large movement. It could be something very delicate and sensitive: just the turn of a head, the look of an eye really make me happy inside as I draw.

AV:Just the same as a musician, who embodies physically the shape, the rhythm and the emotion of the music he’s playing.

GK: Music has always been so integral with the animation. If I’m animating and I don’t have the music yet, I will find a piece of music. Like for Beast’s transformation, I animated all of that to Beethoven’s Ninth. Afterwards we scored it, but in my mind it’s always the Ninth that I hear when I see that animation. The same, on Rescuers Down Under, I was animating to Aaron Copland’s Fanfare For The Common Man as the eagle is flying. I have music in my mind as I’m animating. On Nephtali, it was very helpful to have a composer in Paris, Arnaud Vernet Le Naun, be sensitive to my animation and really try to bring out as much of that spiritual longing and turmoil and freedom. It was just as important for him to have those themes working in his mind, just as it was for Marion Barbeau.

Music does enter in through a backdoor. It doesn’t go through the eyes. It comes in and it touches us deep down inside and you are surprise by the joy, surprised by the sadness, surprised by the wonder. Those are the experiences that suddenly are surging up in you, and it’s the music that’s popping those emotions out of the well. As an animator, you have to use all that is at your disposal to touch the audience. Music is such a vital part of animation. I want to keep going and exploring that way.

These ideas, for me, have been surfacing more and more over the years. The seeds of what I’m doing now have been planted like a decade before. These are so many elements in Duet that are similar, echoing the same themes in Nephtali as well. And I have other ideas that I’ve been developing that echo the same ideas. That’s precisely what I’m working on presently…

Be sure to watch Nephtali here

Filled with great admiration, we express our gratitude to Glen Keane. Very special thanks to Fumi Kitahara.