Studio Ghibli (2013), Touchstone Home Entertainment (November 18, 2014), 1 Blu-ray + 1 DVD, 127 mins, 1.85:1 ratio, DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0, Rated PG-13, Retail: $36.99

Storyboard:

A young man with dreams of flying becomes an aeronautical engineer. His career leads him to working indirectly for a government who plans to use his designs for war. Jiro applies the same straight-ahead thinking to his relationship with his girlfriend, who is battling a terminal illness.

The Sweatbox Review:

Hayao Miyazki is admired the world over for his brilliant animated films. Over the past few decades, he has created magnificent fantasies for grown-ups, and charming family enchantments. Examining his work reveals his passions: a desire to live in harmony with nature, a preference for pacifism, and a love of airplanes. With The Wind Rises, we have supposedly been given the final feature film by Miyazaki, who has announced (though not for the first time) his retirement from filmmaking. The nature of this film makes it feel like a final film, too, being less fantastic and more grounded in history than his past works. This is a romanticized and in fact fictional biography of a major figure in Japanese history, a man who had impressive achievements, though not always admirable ones.

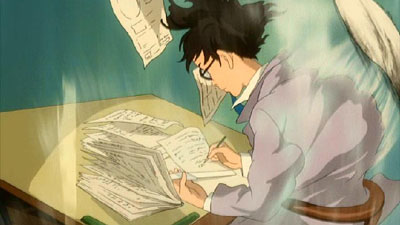

Even as a young boy, Jiro Horikoshi has aspirations to fly, but his weak vision means he will never qualify to be a pilot. In early 20th Century Japan, airplanes are seen as majestic, almost magical devices, and Jiro yearns to harness that magic, to escape his normal life and take to the sky. His admiration for Italian airplane designer Giovanni Caproni, whom he reads about in magazines, leads to Caproni appearing in Jiro’s dreams. In one dream, Caproni tells Jiro that he can still design planes even if he is not allowed to fly them. In fact, Caproni has never flown a plane either. Jiro realizes that his fascination with planes can be well addressed by becoming an aeronautical engineer.

Jiro is extremely bright, and grows up to attend university in order to fulfil his dream. One day in 1923 on his way to Tokyo, the Great Kanto earthquake strikes, heaving the ground in a spectacular animated sequence of rolling terrain. The aftermath leads to the destruction of Tokyo (and other cities) by building collapse and fire. (According to actual historical record, over 100,000 people were killed by the outcome of the quake.) While people flee the burning city, Jiro moves away from his derailed train to help a woman who has broken her leg. She has a younger girl with her, and Jiro ensures that they both reach the girl’s family safely. The girl sees Jiro as a hero, and that perception is not to be lost on the audience, who see Jiro leaving the girl’s family with a smile on his face, declining to give his name as he fades away into the crowd.

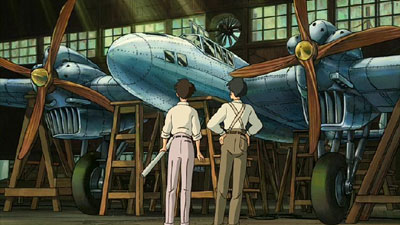

Once Jiro graduates, he joins his friend Kiro in beginning work at the Mitsubishi aircraft plant. They lament how “backwards” Japan is, as they are forced to work with wood and canvas when they know that the future lies in metal aircraft. Mitsubishi is after military contracts, and opportunities arise for the designers to travel to Germany and meet with German engineers. Despite some reluctance from the Germans, the Mitsubishi team gains knowledge on aircraft construction and the use of metals, and they return to Japan ready to impress their bosses. Jiro continues his dream-based friendship with Caproni; it is in these dreams that they share their passions for planes, and concede the necessity of working on military contracts in order to follow their dreams.

After a disappointing test flight at the plant, Jiro goes to a summer resort and meets Nahoko, the girl— now grown up— whom he had assisted after the earthquake a few years earlier. They fall in love, and Jiro promises to marry her, despite her chronic illness from tuberculosis. Her illness is not their only challenge, as they also have to contend with the Japanese secret police, who know that the couple befriended a wanted German at the resort.

Jiro shows tenacity both in his pursuit of his airplane designing dreams, and his relationship with Nahoko, but both pursuits are to end badly. Nahoko’s medical condition is incurable, and Mitsubishi’s success in gaining military contracts, thanks largely to the work of both Jiro and Kiro, means that their aircraft will be used for Japan’s imperialistic aims. Jiro’s biggest success is the Mitsubishi A6M, nicknamed the “Zero,” a plane which became the most prominent fighter plane for Japan in World War II. At the end of the film, Caproni appears to Jiro one more time, sharing the belief that the world is better because of their airplane design work, even though it is regrettable that their planes were used for war.

And therein lies the difficulty in appreciating this film. Miyazaki is a known pacifist, and his films frequently carry anti-war messages, as well as dealing with themes of harmony with nature. Yet, he also loves airplanes, including warplanes. His films often feature aircraft; and his Porco Rosso is even a film with a pilot for a lead character. It is also no coincidence that Gianni Caproni was the designer of the Caproni Ca.309 “Ghibli,” a plane that provided Miyazaki with the name of his animation studio. So, in The Wind Rises, Miyazaki tries to deal with his love of airplanes, while conceding that the institution of war was what led to the development of some of his most admired planes.

It is an uneasy pairing of ideas. While Caproni and Jiro do not necessarily approve of the use of their designs, they also do not seem particularly tortured by it. The attitude seems to be that the engineers only did what their employer needed, at a time when jobs were not plentiful. Jiro and his friends live well, earning very good salaries while much of the country remains mired in poverty. While Jiro’s motives may be open to interpretation, it was my impression that Jiro remained thrilled with the excitement of making his designs better, and seeing his plans realized during test flights. The fact that his planes would kill many, many people over the next few years was maybe regrettable, but it seemed to be a small price to pay for the opportunity to do work he loved, and to be paid well for it, not to mention do some extra travel besides.

It is a difficult thing to reconcile. Was Jiro simply caught up in world events while just “doing his job?” Given also how he treated his relationship with Nahoko, I can only conclude that he was a dreaming, selfish sort. He preferred to keep Nahoko with him, rather than let her live at a sanatorium. Yes, it was her choice as well, but when she eventually leaves Jiro to return to the sanatorium, it is telling that she has to sneak out to do so. I do understand that she did not wish to burden him with her illness; but Jiro was shown to be also reluctant to listen to the advice of his sister, herself a doctor, who insisted that Jiro should let Nahoko go away to get as healthy as possible. When faced with competing forces of passion and facts, Jiro tended to favor his passions.

And yet, perhaps we can still admire Jiro for his brilliance, his work ethic, and— yes— that passion for both his work and his lover. That seems to be what the film would like us to do. Of course, to Western audiences, it is difficult to cheer on the designer of the lethal Zero war craft, or to celebrate his achievements, while watching him accept the deadly uses that the government would have for his planes. It could be argued that perhaps we are not meant to cheer him, but the film does try to portray Jiro as a heroic figure, at least early in the film; his character is worthy of the title when he rescues Nahoko and her maid. That Jiro later allows his passions to blind him is certainly human, but also quite troubling.

Passion is a driving force for people, but it can also be corrupting. Jiro builds beautiful airplanes, but they are used for war. Jiro dearly loves Nahoko, but cannot always bring himself to do what is best for her. Even Nahoko is complicit in her avoidance of dealing with her chronic health issues, due to her longing for Jiro. Does this make them bad people? And, for the purpose of reviewing this film… does it matter? As Caproni suggests, we are all subject to the forces of history, sweeping us along as we try to make the most of our opportunities.

It is ironic that Miyazaki chose this story for his career’s crowning achievement— a difficult story about a man whose passions led him astray. There are times while watching The Wind Rises that I feared the same thing had happened to Miyazaki. One could not be blamed for reacting negatively, or with mixed feelings, to this movie. The subject matter does not lend itself to easy endorsement. However, it is still a film to be admired for its craft, and for giving us something to think upon. And, as a reportedly final subject for its complex director, it is a suitable end to a remarkable career in animation.

Is This Thing Loaded?

The Wind Rises: Behind The Microphone (10:47) examines the makers of the English version of the film, from producer Gary Rydstrom, to the all-star voice cast. I like this type of featurette, but always lament the lack of a similar one for the Japanese side of the production.

It wouldn’t be a Studio Ghibli disc release without Storyboards, and we do get the complete film in this manner, playing with the Japanese soundtrack.

Original Japanese Trailers And TV Spots (9:07).

Announcement Of The Completion Of The Film (1:22:46) is a lengthy, hosted press conference with Hayao Miyazaki, plus the voice of Jiro (who is also a Ghibli crew member) and the singer of a song from the film. Anyone who wants to get an idea of what Miyazaki was trying to accomplish in his film should give this a look. He addresses the highly fictional nature of the storyline, and the intent of the film.

The DVD has Big Hero 6 and Clone Wars trailers (the latter of which is also on the Blu-ray), and the Behind The Microphone featurette.

Case Study:

Standard Blu-ray case, with a Blu-ray and a DVD on either side of the case. There are inserts for Disney Movie Club and Disney Movie Rewards. The cover slip has the title embossed.

Ink And Paint:

The 1.85:1 image is almost flawless, as one would hope. As is the norm for Ghibli movies, the color scheme is not especially bright, favouring more naturalistic colors. The image is mostly stable, but there are very occasional instances of jittering outlines. Per usual for a modern film, we don’t have to worry about any dust or other physical artifacts.

Scratch Tracks:

Miyazaki chose to keep things simple on the audio front, employing a mono soundtrack. This is a dialog-driven film anyhow, so the extra channels are not particularly missed and my subwoofer still managed to put out some bass during the earthquake scene. The Blu-ray offers both the original Japanese track and the English dub, featuring the voices of Joseph Gordon Levitt, Emily Blunt, William H. Macy, and Stanley Tucci. The Blu-ray also has French subtitles.

The included DVD has the same language options.

Final Cut:

This was such an intriguing choice for Mr. Miyazaki’s last film. Bringing together his interest aviation and his view as an artist examining life’s forces, The Wind Rises presents a fictional account of a difficult historical figure. This comes off more like an art house film, one that forces discussion rather than presenting a simple or easy to love story. Miyazaki’s craft is as evident as ever, with unsurpassed storytelling

| ||

|