Walt Disney Productions (November 8 1973), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (August 6 2013), Blu-ray plus DVD, 83 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition 1:66:1 widescreen, DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1, Rated G, Retail: $36.99

Storyboard:

It’s a foxy Robin Hood and his merry men-agerie as the famous English outlaw’s stealing from the rich to give to the poor exploits are turned into a wildly animated animal adventure.

The Sweatbox Review:

By design or not, it does seem Disney’s occasional pick of titles from its classic animation library that it chooses to update to the Blu-ray format have some kind of connection, if one can be bothered to look for them. The last batch, comprising of The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis: The Last Empire and Lilo And Stitch, represented three consecutive releases in the annual Disney animated line-up, from 2000 through to 2002 respectively, while they were also indicative of the changing face of Disney animation at that time, when musical fairytales were out and more challenging and game-changing fare (straight knockabout comedy, science-fiction, and a blending of the two) were the focus of those particular three films.

The Studio’s three early August titles also share something in common: with respect they pretty much represent something of a creative nadir from consecutive decade of Disney’s films, from 1963’s The Sword In The Stone (never seen as one of Walt’s best even on original release, even though it has some fabulous characters desperately in search of the proper plot), through 1973’s Robin Hood (of which more of below, naturally) and to the 1980s’ Oliver And Company, a feature very much of its time, but one that, even though it towers above the mess of The Black Cauldron earlier in the decade, has never really gained the overall popularity of the later Disney Renaissance films or even a fondness enjoyed by other such secondary pictures as The AristoCats or The Great Mouse Detective, though it’s an extremely enjoyable film.

Robin Hood probably enjoys a little more popularity still: as one of Disney’s earliest VHS releases – and one that routinely seems to stay out of the vault for longer periods than most – it’s become a bit of a mainstay in Disney home video libraries, and the animal cuteness factor of its cast must be one reason it remains a borderline classic. Actually, as Disney continues to update their classically animated films to the hi-def format, it’s great to see that even the so-called also-ran pictures are being deemed worthy of such treatment (although in the case of The Sword In The Stone it looks as if a perfectly reasonable HD transfer has unfortunately then been subjected to a child’s crayon interpretation overlay). The Studio has been kinder to Robin Hood, but whoever seriously thought we’d ever see such a film, a middling outing from a Studio in the midst of its directionless 1970s period, given a full digital makeover?

With Walt’s passing at the end of 1966, the Studio that bore his name continued to tick over at first, largely because of the teams he had put in place to oversee continuing projects in the film division (The Happiest Millionaire and The Love Bug were due to be big 1968 releases, the Herbie movie would be the highest grosser of the year) as well as across the theme parks (Walt Disney World in Florida was in the planning, although it would never be fully realized as Walt had intended) and in animation, where Winnie The Pooh And The Blustery Day would become a 1968 Academy Award winner for Best Animated Short and the immensely successful The Jungle Book would also take home Oscar gold for Best Song along with its chart-topping soundtrack sales.

Walt Disney Productions was largely on a high at a critical time, the board headed by Walt’s brother Roy O. Disney (Roy E.’s father) continuing to play safe by asking “What would Walt have done?” whenever decisions needed to be made. However, Walt wasn’t the kind of guy anyone could ever second guess, and his unpredictable and daring nature probably meant that whatever anyone thought he would have done…he would have done the complete opposite! The Jungle Book and, to a large extent, The AristoCats had both been projects overseen or approved by Walt himself, as had a steady stream of live-action films, but as cinema audiences tastes changed with the coming of the edgier 1970s, Disney’s wholesome family output was suddenly in danger of looking out of date.

As opposed to changing tack – something that wouldn’t really happen until the Studio received a wake-up call under its later Ron Miller stewardship and the Eisner/Katzenberg regime created the risqué Touchstone banner – Roy ploughed ahead with Walt-styled projects. The ambitious but ultimately impossible to crack story of Chanticleer fell by the wayside, but a slew of Walt-era projects, such the Sherman brothers’-composed Bedknobs And Broomsticks that Walt had optioned should Mary Poppins not go ahead, and a continuation of the Herbie series and the silly but fun Dean Jones and Kurt Russell style of comedy were the order of the day. These were relatively cheap films to make, and ones that, while not exactly groundbreaking, families knew they could enjoy and take the kids to.

On the other hand, the animated films that were the cornerstone of the company were more costly to produce, and the expense lost on Chanticleer hadn’t gone unnoticed. There was a move – not for the first or last time – to shutter the animation department unless films could be made at more restrictive budgets and be sure to make a profit. Sticking to the ethos of attempting to pick projects that Walt would have approved of, the Studio looked back on its own library and picked the story of the English outlaw Robin Hood, who stole from the rich and gave to the poor. The most famous version, of course, had starred Errol Flynn, in Warner Brothers’ 1938 classic that set the tone for most editions that followed. As one of three English set and shot films that Walt made with British actor Richard Todd, The Story Of Robin Hood And His Merrie Men had proved to be a popular remake both theatrically and when it played in two parts on the Disney TV show.

With Robin Hood a pretty safe bet, the question was raised as to why it should be retold in animation as opposed to live-action, where it was already a proven property. Once upon a time the single most important reason to make an animated film was because its characters or subject matter could only be realised in this medium, and if the Studio’s new Robin Hood was going to follow a path previously trod then there was little reason to do so! Perhaps, as I have always presumed, because of Chanticleer’s all-animal but human-acting proposed cast, the reason to animate Hood was that the Merrie Men were to become the Merrie Men-agerie (as the publicity would also have it), casting classically cute Disney animated animals as the legend’s characters.

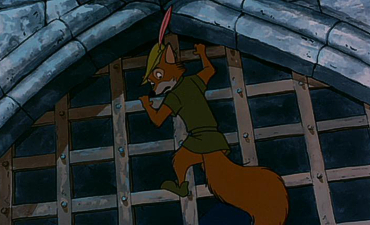

So the wily Robin himself perhaps naturally becomes a fox, while the traditionally oxymoron-named Little John is a Baloo-style bear in more ways than one: wanting to capitalise on the vocal success of The Jungle Book and The AristoCats’ male lead, Phil Harris was brought back once more to bring a jovial and ultimately familiar feel to Little John’s character who, in a spate of much needed cost-cutting at the time, also resembles his Jungle Book persona visually so as to even reuse some moments of animation. And this, frankly, is where those who choose to criticise Robin Hood can all-too easily find their target and hit the bullseye every time. For if there’s any movie in the Disney canon that is as economically made as can be, then Robin Hood is it.

Fans of animation don’t need to look far: the Baloo/Little John similarity is all-too obvious, but look again at Maid Marian’s dancing during one sequence and the eagle-eyed will noticed it’s based on the same live-action reference as Snow White dancing with three of the Seven Dwarfs. At other points, a crocodile from Fantasia and elephant gags from Jungle Book are recycled for comedy effect, and even within the same sequence of this same movie, shots are sometimes repeated (albeit with different timing, backgrounds or soundtrack tweaks). Essentially, Robin Hood was that rare thing: a Disney movie made on a budget and a tight one at that. Yes, the Xerox process is perhaps the most ugly and sketchily used example in the Disney line-up from this time, and clean-up may not have been as precise as before or after. And, yes, some of the storytelling and gags may not always be top tier.

But in many good ways, Robin Hood just works. From country balladeer Roger Miller’s storyteller Allan-A-Dale’s opening whistle theme – music that I still believe Disney doesn’t realise was “borrowed” outright for the Crazy Frog phenomenon of a few years back – to the later moments of real excitement, drama and daring, this is one of the Studio’s tightest told stories. The legend is a pretty solid one to base any story on for a start, but the film delights with its varied vocal casting – which manages to pull off the classic animation trick of mixing English, American and other accents without question – and amongst the budget conscious animation there are still some worthy touches and ambitious scenes, such as some of the first examples of using backgrounds in perspective to show characters walking “towards camera”, the overlaying of matte shots to create depth, and even the simple but effective idea of coloring Prince John’s eyes yellow.

The film also continues to inspire and be remembered today. When Pixar’s Brave debuted last year, much was made of the bow and arrow contest sequence: had it been intentionally referenced by Brenda Chapman and her team or was it that audiences had simply made a natural connection between the two films’ similar moments? Whichever it was, Robin Hood proved not to have been forgotten, and indeed seemed to have become something of a classic itself, fondly remembered with warm memories. And with good reason: despite some of the necessary cost-cutting, it’s just an enjoyable romp, from the fully animated main titles to the brisk, efficient storytelling that features a number of memorable characters delivering some choice dialogue.

Chief among them must be the other big-name castings: Monica Evans (as Marian) and Carole Shelley (as Lady Cluck) reprise their double-act last seen as the two geese in The AristoCats, while Peter Ustinov is a spoiled brat Prince John and his hissy-fit sidekick Sir Hiss is voiced by terrific English cad actor Terry-Thomas in unbelievably his only Disney outing. Thomas is such an instantly recognizable face and voice (seen, more noticeably in Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines, a whole slew of classic British comedies, and an equally star turn in It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World) that it actually helps to forgive the fact that Sir Hiss is another Jungle Book recycle, essentially giving the python Kaa a gap in his teeth to match Thomas’ but, arguably, creating just as an original animated character in the final result.

Playing off the snake is scrawny lion Ustinov, a classical stage and screen presence who should need no introduction but is possibly one of those actors in danger of being forgotten due to the passage of time. He is perhaps best known on film for a trilogy of big screen Hercule Poirot films as well as donning the Charlie Chan make up for the largely ineffectual but still occasionally funny Curse Of The Dragon Queen in the 1980s; just before Robin Hood he’d been in the clever accounting comedy Hot Millions, afterwards he would stick with Disney’s for the excellently bonkers One Of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing opposite Helen Hayes. Here, he’s mostly comical, but there’s always a truly menacing side, and when he later appears as John’s brother Richard, the effect is subtle but totally acceptable.

In the rest of the soundtrack, the usual Disney magic just about holds sway, although the mix of songwriters reveals itself through the not-quite meshing of styles from Miller’s scatting (Not In Nottingham remains one of my favorite Disney songs), and the soppy, romantic and lyrically feeble Love ballad sung for Robin and Marian (a typically drippy Seventies number of the kind that peppered the Studio’s films of the time, written by Floyd Huddleston and George Bruns, who also scores), to Johnny Mercer’s The Phony King Of England, sung by Harris as what can only be described as an attempt to mirror the success of The Bare Necessities, although the film’s one and only Oscar nomination ironically went to Love, a song that has all but vanished from any Disney song compilations.

Robin Hood, despite some clear issues, still entertains profusely. The action is well handled, the relationships between the characters, and their dynamics with others, are played to all their strengths. Even the reuse of Harris as a big bear and a similar snake in Sir Hiss don’t seem to detract, Thomas’ physical resemblance and vocalizing arguably making Hiss the perfect match of animated visual and voice until Robin Williams’ Genie came along nearly 20 years later. So overlook whatever shortcomings you may see (or want to see) in Robin Hood, and simply enjoy the kind of film it was meant to be: an economically told and important film for the Studio, which proved these kinds of films were still viable entertainments and, more importantly, that there was still a sizable audience for them.

Disney animation after Robin Hood is interesting to look back on: with all eyes on this feature to see how it performed at the box-office, there was a distinct lack of purely new content to emerge from Disney’s in the three or four years after its original 1973 release. A new Winnie The Pooh featurette, Tigger Too, kept the animation staff ticking over, but many of the other shorter subjects (Dad, Can I Borrow The Car?, Man, Monsters And Mysteries, etc) featured only limited animation sequences amongst mostly live-action settings. With a terrific public response Robin Hood, Disney Animation was viable again, leading to the 1977 double-punch of The Many Adventures Of Winnie The Pooh and The Rescuers, which became the highest grossing animated film at that time. Poor Robin doesn’t usually get the respect he deserves, but this new edition should hopefully make everyone thing again.

Is This Thing Loaded?

As with Disney’s other August 6 titles, Robin Hood finds itself not hugely endowed with extras, but it does manage to fit in at least one or two new surprises. The Studio’s current trend of updating their films on Blu-ray format as quickly as they can is surely either a good thing or a bad thing: yes, it means our shelves can get stacked up sooner than later with the classic features – with only films from the 1940s and 1990s to come before we ostensibly have complete collections – but it also means these BD updates don’t always get the full attention they should. With the producers of these efforts choosing to base new releases on the last available DVD edition rather than starting from scratch and awarding each title the respect they deserve, we’re losing the opportunity for truly definitive editions, complete with archival materials that would retain all previous extras and bring something new to the titles for long-time fans.

Fortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case with Robin Hood, which has seen two previous DVD issues, neither of which ever contained much material to begin with. In a nice surprise, and while this new BD primarily bases itself on the past “Most Wanted Edition” DVD, this Hood manages to provide us with the best supplements from each DVD, and there’s even a return to Disney’s earlier BD titles that chose to include at least one new supplement as an added treat. Here it’s a Never Before Seen Deleted Storyline, Love Letters, which has Prince John and Sir Hiss planning to capture Robin by way of luring him in via letters from “Maid Marian”… With animated story sketches presented (unlike most of the rest of the standard definition extras) in HD, this seven and a half-minute sequence adds something of note to this edition, and shows that the Studio does, on occasion, still care about even its supposed secondary features.

From the Most Wanted DVD, some more deleted material shows up in a four and a half minute Alternate Ending, which shows a bit more desperation from a Prince John tracking an injured Robin down, and has a little more interaction between a returning King Richard the Lionheart and his suddenly more timid younger brother. Again presented from animated storyboards and concept paintings, it makes for a sneaky way to see some of the artwork developed for the movie, including a deleted character, something that is surprisingly elaborated upon with a Robin Hood Art Gallery. Originally offered as a stand-alone DVD gallery or as a video “walk-through”, it’s the video-only edition that’s on show here, but it’s fair enough and, despite the child-aimed narration (that otherwise does give us a few good facts), the near nine minutes does offer plenty of scope in looking at Hood’s production.

While not the most exciting supplement from the film’s original Gold Collection DVD, and perhaps smacking of pure desperation in attempting to fill the package’s promise of “over an hour of extra content”, a Robin Hood Storybook recounts an almost 15-minute telling of the film’s plot, again presenting just the video version of what was also offered as a gallery-style page-turner on the Gold DVD. A Disney Song Selection option presents the film’s four song sequences in a single line-up, while there’s also a Sing-Along subtitle track that pops up during the movie’s songs, and a two minute Oo-De-Lally Sing-Along is pretty fun, covering Miller’s take on the Robin and Little John relationship from the beginning of the film with a selection of clips from throughout the movie. Although most of these extras are AVC-encoded and sport high bitrates, they’re not true HD, looking like quality upscaled editions if anything.

What is a terrific bolt from the blue – or Blu, if you prefer – is that the previously included classic cartoon Ye Olden Days, colorized on Hood’s Gold DVD and in original black and white on its Most Wanted Edition, appears again here, although this time in a wonderfully restored HD. Whether this makes picking up Robin Hood more of a pick-up necessity will be down to how much you either like the cartoon or are actively attempting to collect as many of these shorts in HD as possible (surely a frustrating challenge if ever there was one, Disney is long overdue releasing their cartoons in HD). Featuring Mickey and Goofy precursor Dippy Dawg after princess Minnie, this is a mini-epic, full of the kind of touches that propelled Walt’s Studio to the forefront of animation.

Mostly included because of its time setting, this is nonetheless welcome to see again: why it is in HD (when similar recycled cartoons on The Sword In The Stone continued to use dated 1980s video transfers!) is an open question, but perhaps the Studio has begun to methodically work its way through the shorts library and we may yet hope for definitive Disney cartoon compendiums to make their way to Blu-ray soon…? That’s it for the hi-def extras but on the enclosed DVD the Alternate Ending, Art Gallery and Ye Olden Days are repeated alongside two set-top games, as are Sneak Peeks previews which, across both discs, include The Little Mermaid, Planes, The Lion King musical on stage, The Muppet Movie, Return To Never-Land and The Many Adventures Of Winnie The Pooh among others.

Case Study:

I’m not sure if Disney has recycled Robin Hood’s cover art from a previous issue, but it certainly has a whiff of familiarity about it. Then again, each edition of the movie on home video has stuck to the essentials of showing Robin with his bow and arrow, some peripheral characters and, usually, a target, so one can’t begrudge the similar tack here, and it must be said that it’s a fairly balance image that recalls some earlier editions, even down to the bullseye featured in one of the title’s letters, and it’s nice to mention the film’s 40th birthday. The rest isn’t too exciting: inserts are restricted to Rewards code and Movie Club promos, and the back’s doubtful “before and after” shot of the digital restoration actually removes image information! At least this new batch of August Disney titles give us a listing of their packages’ contents, even if there’s still no mention of an aspect ratio! Speaking of which…

Ink And Paint:

After the detestable debacle of The Sword And The Stone’s unfortunate and heavily DVNR’d image left such a bad taste, worries about how the rest of Disney’s August 6 titles would measure up become something more of a concern. While not escaping the DNR brush completely, it’s good to be able to report that Robin Hood sports a fresh and clean transfer that’s nowhere near as colored with crayons that Stone’s pathetically poor picture sports. On the flipside, the actual aspect ratio is still in question, the lack of such tech specs on the back of the sleeve not helping anyone to make an informed purchase! As commented on at length in my Stone review, the bottom line is that Walt’s widescreen pictures Lady And The Tramp and Sleeping Beauty, both of which replaced the Academy framing of every film from Snow White to Peter Pan in the 1950s, Disney animation followed general presentation trends that shifted towards a generic widescreen process that took a regular 1.37:1 frame and masked top and bottom to present the now standard 1.85:1 aspect ratio we still see today.

With the then-1.33:1 television screens a major force in how a move would be seen after its initial theatrical showings, many producers opted to shoot their films to a “protected” 1.37 Academy frame, allowing theaters to mask the top and bottom for a widescreen presentation (protected in the framing so as to not crop heads or important image information) and television screens to “open matte” the masking so that picture would not be cropped from the left and right of the image (more cumbersome to reframe for even with the dreaded pan-and-scan process). By the time of Robin Hood, Disney’s films were designed as such, framing for theatrical widescreen and leaving space top and bottom for later TV showings long before home video and HD were ever dreamed of. While it can be argued that both versions (an intended theatrical widescreen ratio and the original negative aspect) are valid and could be included, it’s fairly obvious that each movie from One Hundred And One Dalmatians until The Fox And The Hound (preceding a return to CinemaScope-styled widescreen with The Black Cauldron) has been framed with the intention of cropping the top and bottom.

The amount of the crop is debatable – theaters would have gone from anything of a European 1.66:1 to a general 1.75:1 (close to the 1.78 of 16:9 HD) and a worldwide “hard matte” standard of 1.85:1, which would alter depending on where you saw the movie in question (I recall a 1.85 cropping of Snow White, a film never intended to be framed this way, and it was as atrocious as you can imagine). After Cauldron’s 2.35:1 epic approach, the Studio settled on the theatrical and TV-friendly negative compromise of 1.66:1, which meant less of a crop theatrically (to 1.85) and on home video (at 1.33), leaving LaserDisc and more latterly DVD and Blu-ray to accurately present the entire 1.66 image area. Personally, if we’re taking the Studio’s 1.37 films and looking at presenting an accurate widescreen image that represents integrity for both aspects, then I don’t think you can go wrong with the same 1.66 ratio, which preserves the left and right of 1.37 and crops a minimal amount top and bottom, creating the intended widescreen framing without removing any significant image information.

Perhaps some of the earliest films created in this dual format didn’t quite leave enough space for such cropping, but by the time of Robin Hood, it is clear that it’s a wider ratio being framed for, and it’s the later television showings that have become the afterthought. As such, it’s good to see Hood in the 1:66:1 ratio that it has been given here, and it even ups the production value so as to look and feel a little more like an A-class feature that somewhat glosses over the more budget approach to the project (and I’m glad that a tighter 1.75 aspect from a previous DVD has been dropped). Robin Hood, from the wide-safe main titles, was clearly framed for a widescreen ratio, and the 1.66 ratio allows for the best of both worlds.

In terms of restoration, I was perhaps expecting (and hoping) for a secondary level transfer of essentially a clean film print element given some HD love and care. We do get that here, but whereas The Rescuers, to pick a film from the same timeframe, retained some grain and a pleasing color palette, Hood has been given a slight, additional digital pass. These efforts are not as damaging as Sword In The Stone by a long shot, and they thankfully retain all the image and pencil line detail. A thin layer of grain is still there, and some occasional flecks, print and cel marks are still visible if one looks for them, so this is on balance a fairly pleasing transfer and, even if it’s a little too artificially scrubbed for my liking, it does faithfully represent the original movie and is easily the best Robin Hood has ever looked on home video.

Scratch Tracks:

Whereas Robin Hood’s image survives intact and cleaned up to a reasonably decent degree, the limitations on the soundtrack mean that very little can truly be done to make this particular picture sparkle on the aural side. A typically thin aspect to the soundtrack, easily datable to 1970s recording techniques, especially in the mixing of the film’s musical score, is easy to trace its restrictions back to, and when the packaging promises a DTS 5.1 mix it’s a technical specification that should be taken fairly lightly by those with elaborate home theater set-ups.

That said, the engineers behind this update have done what they can: there is some separation even if this does feel like a front-heavy stereo track that’s been occasionally widened up to give a feeling of surround activity and lacks a full sense of authenticity as a result. But dialogue is abundantly clear, the spot sound effects never feel out of place and, while the budgetary considerations mean the animation wasn’t the only thing to have been reigned in and though the track can’t measure up to the multi-layered mixes of today, Robin Hood still sounds fresh enough and probably better than it did on its original debut.

Final Cut:

The extras stretch themselves to just about provide the “over an hour of extra content” the back of the sleeve promises, and Disney’s current packaging design means aspect ratio specs are still a no-show, while the digital restoration isn’t quite as delicate as it might be (but doesn’t approach the dreadfully unpleasant results of Sword In The Stone either), but Robin Hood still hits the bullseye in terms of the original film being fun and Disney’s disc providing a decent if not stellar HD treatment. Not every film from the Studio deserves the two-disc Diamond touch, naturally, and while perhaps the nostalgia in me suggests Robin Hood could deserve a little more than it receives here, most should find that a good presentation and smattering of extras is right on target, even if the $37 list price (instead of a Disney-standard $30) feels a little like the rich stealing from the poor…

| ||

|