Walt Disney Pictures (October 5 2012), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (January 8 2013), Blu-ray 3D plus Blu-ray Disc, DVD and Digital Copy, 87 mins plus supplements, 1080p 1.85:1 high-definition widescreen, DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1, Rated PG, Retail: $49.99

Storyboard:

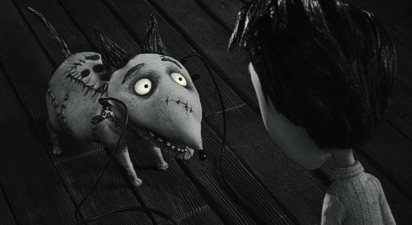

In a stop-motion remake of Tim Burton’s own live-action featurette, young Victor Frankenstein’s dog Sparky is brought back to life via the lightning-harnessed power of electrickery…

The Sweatbox Review:

I really, really, really wanted to like Frankenweenie. In fact, being the huge Tim Burton fan that I am, I wanted to love it. The director may have his detractors, but I’m always interested in seeing his latest releases and have been since I snuck into a theater just a little too young to see Beetlejuice way back in 1988. Actually, I guess you could say I was a fan right from Burton’s feature debut, Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, which I later saw on video after Beetlejuice had impressed so much. Teaming Burton with his regular composer Danny Elfman for the first time, Pee Wee’s Big Adventure was ostensibly a vehicle for comic actor Paul Reubens, but it was Burton’s staging, touches of stop-motion visual effects, and Elfman’s rambunctious musical score that I came away remembering.

Next up was the behemoth of Batman, too often overlooked nowadays in light of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight update but just as impressive, and perhaps more so, as those films in terms of visual achievements, and Burton’s Batman Returns was, for the time and even now, even more psycho-twisted, darker and warped than Nolan’s own Joker-featuring sequel. Coming between those two was Edward Scissorhands, probably the first true film to coin the term Burtonesque in terms of his story approach and visual style. Batman may have influenced comic-book movies from 1989 onwards, but Scissorhands was the feature where Burton’s own characters came to the fore along with his Rick Heinrichs production design elements.

As is now well told, the two had both started at Disney in the 1970s and hit it off due to their similar design tendencies – call it “gothic light” – collaborating on Burton’s first films, the stop-motion short Vincent, and Frankenweenie, produced in live-action when the script proved too long and ambitious for the kind of stop-motion film Burton originally had in mind as a Vincent follow-up. Cut to the late 2000s and, after a phenomenal career that has seen Burton making a healthy amount of movie money for both Disney and his other most usually associated studio home of Warner Bros, home to Pee Wee, Beetlejuice and Batman. Burton first returned to Disney for 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, produced at a time when Disney Animation under Jeffrey Katzenberg was undergoing a huge creative and risk-taking renaissance.

The global success of The Lion King was to come mere months after Nightmare’s release, and the first computer generated movie, Toy Story, was just two years away. Since any formats and projects Burton had created while at Disney’s were rightfully owned by the Mouse House, when the director originally inquired as to whether he could buy the rights back, Katzenberg – not missing the phenomenal success that had been brought to Warners under an unofficial Burton brand – made a counteroffer suggesting Burton come make it for Disney. The result was a unique collaboration, directed by another Burton-Disney colleague, Henry Selick, and released under the Touchstone Pictures banner when it, like Who Framed Roger Rabbit before, proved to be a little outside the usual Disney lines.

Although not a huge hit on original release, Nightmare, as with Burton’s Scissorhands, drew a large cult following theatrically and especially on home video, and is now rightly regarded as a classic, airing annually on TV each Halloween or Christmas. Burton and Selick maintained the stop-motion momentum with James And The Giant Peach, a largely undervalued feature that proved there was something about stop-motion that suited material of a more quirky nature but it was a film that ultimately failed to find much of an audience. The team disbanded again, Selick and his team moving on to other stop-motion work (including sequences for Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic and the brilliantly insane MonkeyBone), and Burton returning to live-action filmmaking, using his new clout to bring his personal Ed Wood biopic and the certainly Wood-inspired Mars Attacks! to the screen.

If nothing else, The Nightmare Before Christmas reaffirmed an almost unspoken connection between stop-motion and what can only be called “spooky” material. From the earliest days of the medium, animation has been used to do what live-action could not: bring inanimate objects to life. Often this included the dead and other spine-chilling or unpleasant elements, from Winsor McKay’s How A Mosquito Operates, and Walt Disney’s first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance (which raised some pretty funky bones from the graveyard and inspired many films over the next decade) through many of Max and Dave Fleischer’s strange excursions into the surreal in their Betty Boop cartoons, to George Pal’s Puppetoon series in the 1930s, which often featured a terrified character called Jasper, who got himself into many a paranormal jam.

Out of all the animated methods, stop-motion seems to have found a natural bonding with such subject matter over the years, especially in recent times when the holiday specials from the Rankin/Bass studio especially became synonymous with establishing a link between the medium and often melancholic stories. They may well remain best known for their Christmas programs, but check out their other work and remember they also made the original Halloween musical feature Mad Monster Party in the 1960s. Nightmare was a direct descendent of these films, and swung attention back to an animation technique that had become all-too dormant following the legendary Ray Harryhausen’s imaginative but less and less frequent touches in effects-heavy motion pictures and used more prominently around the world (such as England’s Aardman studio) or almost exclusively for promo commercials.

Nightmare’s reach cannot be underestimated: the film almost independently spawned at least two new feature animation-capable units and eventually became a fully fledged franchise now welcomed by Disney: either because of relaxed audience attitudes or because the Studio wanted to bring Jack Skellington and friends into the established library of characters, the film is now presented from Walt Disney Pictures and has even inspired an annually-themed takeover at Disneyland. Burton has always resisted producing a sequel but has remained at the forefront of the modern stop-motion revolution. Before Nightmare was fully established, Burton’s Corpse Bride followed for Warner Bros, a film that shared a lot in common and upped the animation fluidity, but failed to engage with audiences in the same way even if it did cement the combination of stop-motion and spooky Halloween atmospherics as blood brothers.

Even when Burton hasn’t been directly involved, such as with Selick’s Coraline and that Studio’s more recent ParaNorman, the same feeling is present, and even when Aardman finally transferred their Wallace & Gromit characters to the screen for The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit it was in a jokey homage to Hammer Horror, of which Burton is also a confirmed fan as emphasized by his takes on Sleepy Hollow and Sweeney Todd. In amongst the plethora of shiny, computer generated toys, cars and animals, however, at least these stop-motion films stand out from the crowd, the recent success and surprise Oscar nomination of Aardman’s The Pirates! being a welcome addition to a list that also features ParaNorman and Frankenweenie to the more predictable CG pairing of Brave and Wreck-It Ralph.

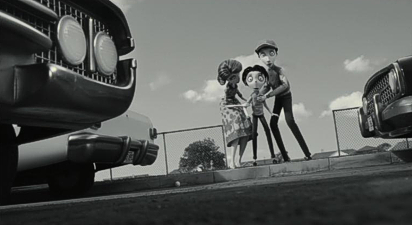

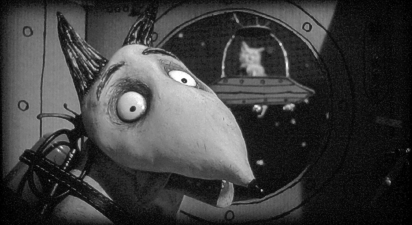

Frankenweenie perhaps sticks out more than most: as well as being traditionally stop-motion animated, it’s also completely in black and white. This is the reason that most will give as to why it didn’t perform too well in theaters last year, but I don’t think it’s just down to this. It’s well known that modern (and foolish?) audiences don’t appreciate the silvery magic of black and white films thesedays, but Burton didn’t even give Disney the chance of releasing a second version in color (as is usually the case, a film will still be shot on color stock and processed in b/w, so that a color edition can later be issued if it is felt it could improve its commercial prospects). This time using digital SLR cameras instead of film, the trick here was that all the sets, props and models were created in various shades of gray, imposing the b/w scheme on everything during the shoot from the get-go.

Would Frankenweenie have benefited from being additionally available in color and could it have made more money this way? Well, no, I don’t think so: the lack of color evokes the kind of film Burton is reminding us of perfectly, and any reason as to why Frankenweenie failed to work theatrically is, to be harsh, because Frankenweenie fails to work convincingly as a movie…it simply, and this is a hard truth…isn’t very good. I can’t even say my expectations were placed too highly: as a fan of Burton’s original featurette I was a little concerned that this was yet another short film that could be stretched out to a less than substantial feature-length, and I’ve seen enough of those to know they usually don’t work. I was excited by the notion of retelling the story through stop-motion, which seems a perfect fit and was Burton’s original intention years ago, but the result, as with the almost concurrent ParaNorman, just isn’t full of enough life or energy, ironically given the subject matter.

With a similar production method and exploring the same kind of themes, comparisons to ParaNorman are inevitable: although Frankenweenie pretty much had the Halloween slot to itself in its US release and most of its international markets, the competing film had debuted just over a month before and it could be that audiences had simply had their fill of this kind of entertainment before the more colorful Wreak-It Ralph came along to own the holiday family box-office. In stark contrast, ParaNorman, even though I didn’t find it too engaging either, was phenomenally well made, its models and craftsmanship second to none, its animation as perfect and fluid as any stop-motion film I have encountered. Which all seems to make the monochrome, extremely simplified and…dare I say it (“Dare! Dare!”)…visual endeavors of Frankenweenie come across a little more reserved and, well, low-budget.

Certainly the production design doesn’t really extend to the kind that we might usually associate with Burton and Heinrichs. Sure, there’s the basic same kind of setting that we’ve seen previously: the Burbank-inspired streets of cookie-cutter type housing, a Scissorhands-styled cul-de-sac that instead of Vincent Price’s gothic castle has a hilly graveyard at its end, and even young Victor Frankenstein’s home is reminiscent of the kind of LA bungalow in which Burton’s Bela Lugosi was visited by Johnny Depp in Ed Wood. The problem is here that there’s nothing really to embellish those stand-bys: the rest of the designing – that is what doesn’t already lift from the original Frankenweenie featurette or Burton/Heinrichs’ past work – is pretty darn feeble and non-imaginative (even Sparky resembles Burton’s Family Dog design for Amazing Stories).

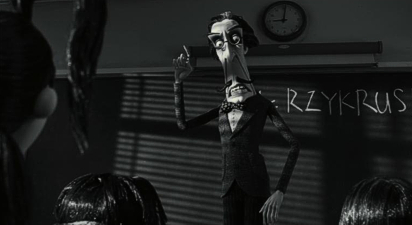

The animal graveyard from the original featurette has been faithfully recreated here, but then it also brings little new to the set: we’ve seen this before (and it actually seems to lose a nice visual poke at Disney’s, via a ruined fairytale castle). The rest of the locations, even the digitally extended ones, just don’t seem that inspired, despite the no doubt impressive amount of handcrafted work that goes into these kinds of films. But the sluggish enthusiasm stretches to other areas of the production, too: screenwriter John August fills in gaps in the expansion of Lenny Ripps’ original featurette script by adding a contingent of Victor’s school friends rather than developing any of the other characters. Mom and Dad remain on the fringes, and the Frankensteins’ neighbors are equally underused, especially in the film’s ending which seems fuddled and not as coherent or appropriate as in the 1984 version.

Some other elements are not as well defined, either: an Elsa Lanchester Bride Of Frankenstein joke – once a very amusing punchline in 1984 – is placed here much earlier, and thus becomes a throwaway moment that doesn’t resonate and provide the same reaction; the first time around it made for a fun nod to the past and raised a final smile (and could have done again here), but as the 2012 edition has it, there is no real point. I was also under-whelmed by Victor’s classmates, who turn out to be such an oddball grouping of misfits that Victor himself – you know, the kid that brings his pet pooch back from the dead – is actually the most normal kid in the classroom! This seems to be out of kilter for the tone of the piece and for Burton in general, whose films are usually about the strange outsider trying to find a place: here Victor is the least nightmarish character despite his reanimating intentions.

Yes, one could say that he is the outsider in a class of nuts, but then why is everyone else relatively normal? The eccentrics are confined to the other kids, especially the Igor-like Edgar (a nod to Poe), and one or two adults in authority – another Burton staple – so that argument doesn’t really stick. And, as if really going overboard to emphasize the dreary tonal quality, the voice cast doesn’t bring much life to things either. It was great to see so many Burton collaborators working with him again, and I was expecting much more from them in terms of working their vocal magic on the pedestrian script. As Victor, newcomer Charlie Tahan simply sounds either inexperienced or just uninterested, while where was the life that Catherine O’Hara (Beetlejuice), Martin Short (Mars Attacks!), Martin Landau (Ed Wood) and Winona Ryder (Edward Scissorhands) brought to their roles in those films?

I guess O’Hara is just Mom-sy enough to convince, but after his exuberant turn in Madagascar 3 Martin Short pulls a complete 180, swapping his sea lion’s slightly crazed demeanor for something so dull that I actually had trouble hearing his performance, so under-energized as it was (he’s unrecognizably better as next door’s Mr Burgemeister). Ryder, too, seems to have simply turned up and read her lines, perhaps putting a little more emotion into them than others, but still adding to a sometimes surreal feeling of no-one being really too bothered about lifting Frankenweenie to anything higher than just being a by-the-numbers remake of an earlier film. The best of the vocalists is easily Landau, but even here he isn’t really doing anything other than lampooning his Bela Lugosi role (even his Frankenweenie character’s design is clearly inspired by Burton’s ongoing fascination with Vincent Price) and comes and goes onscreen so briefly and early enough in the film so as to be quickly forgotten.

That none of the actual animation really strikes home that much doesn’t help things: just watch the way the characters move in very robotic ways, with almost mechanical gestures. Is this Burton’s way of directing stop-motion animation, or something inherent in the animators’ draftsmanship? It certainly wasn’t a debilitating factor in Nightmare or Corpse Bride but continually stuck out at me here, as if the models had been keyframed and the animators were being asked, instead of to act, just to simply put the puppets in the right places. Even the quirkier characters move in these same ways: when the plot, which is also expanded to allow the other kids to attempt to bring their pets back to life following Victor’s experiment, calls for dead animals running amok, none of them really sport their own unique and specific characteristics in the way, say, that the denizens of Halloweentown or the zombies of ParaNorman all did.

Despite moving more recently into the higher echelon, elder statesman styled stage of his career, Burton still makes the same kinds of films as he did when he was younger. That’s to be admired to a degree, but there’s no denying that the director does have his detractors, who say that he repeats himself and essentially makes the same film over and over again all the time. As a defender I prefer to go along with the auteur theory, which suggests a director stamps his personal seal on any project be it originated by them or an adaptation of another’s work. Burton certainly comes up trumps in this area: the studios do not hire him because they want to be surprised, they hire him because they want “a Tim Burton film”, such as the recent Dark Shadows, a previous television show with its typical Burton aspects amped up to perhaps overly obvious levels (it even starred constant collaborator Johnny Depp, who goes missing here but previously voice another Victor for Corpse Bride).

Nowadays Burton is in the fortunate position not to be simply a hired gun. He can instigate his own projects or attach himself to others, but even I find myself wondering if he’s more interesting when adapting previous work (such as Sweeney Todd), than coming up with his own ideas like Frankenweenie. Burton has a well-known well of ideas on which he has drawn from before, most notably with the animated web series Stainboy, but more than anything Frankenweenie feels like a repeat too far. Naturally some of this is to do with the fact that it’s a remake, and so asking the question of why not do something original instead. Okay, so Burton wanted to go back and make the stop-motion feature he was denied in his Disney days before becoming a commercially successful director. However, Frankenweenie also feels like an amalgamation of Burton’s previous efforts, a “greatest hits” compilation if you like, but without any real hits.

More than ever in any of the director’s films, everything is exactly in place, exactly as they should be, and exactly as expected. Even Danny Elfman’s score – something that I always look forward to especially in a Burton collaboration – goes through the plinky-plonky motions, at times seemingly referencing their Batman theme and cues from Edward Scissorhands either intentionally or, more likely, subconsciously. Remake accusations aside, there simply isn’t anything new or innovative to surprise us in Frankenweenie, a film that like its canine protagonist, feels made up from several other parts, none of which add up to a greater whole. I question too the core idea of a child toying with electricity…something that’s treated with fantasy consequences that are naturally unreal and for entertainment but that I hope don’t lead to kids attempting anything along the same lines at home. Perhaps they’d be better off putting that energy into their own stop-motion ideas and coming up with something more unique, because as a movie this Frankenweenie needs a lot more power.

Is This Thing Loaded?

I’m none-too convinced that Disney thought it was worth putting much stock into Frankenweenie going by the brevity of the supplements on offer here. Although the film didn’t exactly electrify box-offices across America, it’s usual for a film from such a major director to still get decent treatment on home video but, as with the movie itself, there’s a distinct lack of enthusiasm gone into this presentation. Naturally, in lieu of a hoped-for Cine-Explore picture-in-picture track, one would be expecting an audio commentary from Burton and his primary team at the very least, all of which would have been interesting in hearing how the director switched mediums, dealt with the alternating facets and communicated with his crew…but there isn’t such a track here.

Likewise we could have expected some deleted scenes, or several documentary featurettes on the production, from story and vocal recording through animation and the 3D conversion aspects…but despite a “set” tour, there aren’t any of those either. This being an animated title, how about a now-standard new animated short made just for this release? Well, okay, yes we get one of those in Captain Sparky Vs. The Flying Saucers – but at just over a measly two minutes short is the operative word! Set up as one of amateur filmmaker Victor’s own home movies, this is a nice little bit of fun, but fairly inconsequential. It isn’t, but it feels more like an alternate or additional clip from the movie; a deleted scene dressed up and completed just to add a “bonus” sticker on the front of the cover.

Miniatures In Motion: Bringing Frankenweenie To Life takes an “in-depth tour of the London set”, and is easily the best of the supplements. All-too brief at just 23 minutes, there is at least some expert editing going on here, and this nifty little doc manages to cover all the bases and speak to the crew, Burton and Disney producer Don Hahn among, without skimping on information. The sheer amount of work that goes into these kinds of films is always stunning, but just as interesting is the stuff that is seen but not spoken of, and I was intrigued to see the amount of “cheats” the film used in terms of armature supports and set extensions, all of them altered digitally as opposed to ParaNorman’s more impressive “real” locations. Nevertheless, this is an essential stop to get an appreciation of the crew’s efforts in creating Frankenweenie.

Of particular interest to me was the hoped-for inclusion of Burton’s original live-action Frankenweenie featurette, which had previously appeared on VHS and in the LaserDisc edition of The Nightmare Before Christmas in a slightly trimmed version. An uncut edition was included as a novelty on The Nightmare Before Christmas’ Blu-ray editions but, alas, this was still from a standard-definition, open matte video transfer. Surely with the ideal opportunity to create a new 1.85:1 high-definition transfer of a unique film in the Disney library the Studio would jump to it? In a word…no. I was hoping that by the time this remake showed up on disc that we’d get the obviously intended widescreen framing (it was masked in theaters), but unfortunately if you have the Nightmare BD then this is the exact same old interlaced version as before – minus the Burton introduction that gave it some context.

As with the remake, 1984’s Frankenweenie is a black and white homage to the horror films the director had seen as a child, featuring 80s NeverEnding Story and D.A.R.Y.L. child star Barret Oliver (of whatever happened to… fame) as the young lad who reanimates his pet dog after a road accident. I actually prefer the tighter 27 minute edition from the LD, since this 30 minute cut’s additional moments (including an extra opening film within a film gag and a couple of non-essential scene extensions mostly concerning parents Shelley Duvall and Daniel Stern) are not too exciting. But Frankenweenie ’84 remains great fun for fans of the director’s work, with many trademark touches, casting choices and thematic elements making their debuts, even if it simply feels dumped in here. Missing it out would have felt odd, but not using the opportunity to give us a new HD edition – and an additional reason for those on the fence with the main feature to consider a purchase – somewhat feels odder!

There’s a further look at the sets and puppet models of the new movie in a four-and-a-half-minute Frankenweenie Touring Exhibit promo that strives to get us interested in a traveling showcase currently making its way around the world. Interesting enough without ever becoming totally involving, the footage from the 2012 Comic-Con doesn’t really show off the exhibit to its best and initially relies more on shots from the film to convince, but it’s a nice idea to appreciate this stuff up close and in detail. Finally, as a token piece of promotional material, the Plain White T’s Pet Semetary music video puts around four minutes’ worth of band-in-a-graveyard and movie images together to accompany a song from an inspired-by album and not Karen O’s end credit track (which themselves run around seven minutes with a bit of Elfman score and reduces Frankenweenie’s actual animated length down to 80 mins).

Even with the relative dearth of supplements to be found on the Blu-ray, the enclosed DVD retains only two of them: the Touring Exhibit featurette and Plain White T’s music video – hardly worth it when the making of piece and two-minute Captain Sparky could have easily squeezed on too. Making up the content here are the usual Sneak Peeks: across all the discs in the pack there are previews for Sam Raimi’s Oz: The Great And Powerful, Wreck-It Ralph, a “nearly 35th anniversary edition” Blu-ray for The Muppet Movie (hopefully uncut), ABC’s Once Upon A Time, Peter Pan: Diamond Edition and a Special Edition update for its Return To Never-Land sequel, plus the now very tired Planes spot, which I suggest everyone will be so bored with by the time the film comes out that it could end up having a detrimental effect! A couple of Disney spots for their Rewards and theme parks round out the package.

Case Study:

Going by the lack of enthusiasm shown towards the bonus features it seems I’m not the only one with a somewhat lackluster reaction to Frankenweenie, with the sleeve art suggesting Disney aren’t one hundred percent behind the title, even if their design – using a variant on a theatrical poster – does try to bring the feeling of some color to the look. For a 3D release, one would expect the Studio’s lenticular fronted slipcover but, as with the also-underperforming Mars Needs Moms before it, Frankenweenie becomes only the second (as far as I know) title in Disney’s 3D line not to sport this kind of touch.

The regular silver border (replacing the standard blue surround on Disney’s 3D releases) is in place, and there’s some intricate work gone into the embossed slip, but otherwise it feels a little less substantial than a usual 3D pack, not helped by the slimline BD case that stacks the discs on top of one another instead of the beefier fold-over trays (nice, though, that the movie retains its proper title and not “Frankenweenie 3D”). Inside there’s a Rewards code and a random promo for “spooky” pistachios (!?), but there’s no escaping the slight waft of Disney trying to minimise expenses here.

Ink And Paint:

Shot on digital SLR cameras, I was excited to see what Frankenweenie would look like in 3D, given that the post-conversion on The Nightmare Before Christmas actually turned out to be fairly convincing, giving a ViewMaster-style appearance to the models if not actually a quite fully-rounded three-dimensional feel. After ParaNorman wowed visually (and was shot in a native 3D process using a genius system whereby the camera would slide across a mechanism to capture the left and right eye views for each frame), I was disappointed that Frankenweenie had also been post-converted instead of being filmed stereoptically, but the results are fairly pleasing.

Maybe the grayscale photography manages to suggest a more rounded aspect to the models in its shading, or perhaps 3D conversion processing has gotten more refined since Nightmare’s transfer, but Frankenweenie largely survives the addition of depth. Clarity is good, too, thanks to the high contrasts in the image that help define some solid hard edges and mostly prevents ghosting, creating more of a depth to the image than going for prop-popping-out-of-the-screen gimmickry – although this is something that might actually have been more fun in this instance, especially towards the end of the movie.

On the regular non-3D Blu-ray, the definition is just as good, but the spotless image doesn’t really help the mechanical feeling of the animation. Non-dimensional depth is actually very good thanks to Peter Sorg’s lighting and depth of field focus that keeps the foregrounds sharp and the backgrounds soft in shadow. I did question the framing in a couple of instances, especially during the opening titles, when a couple of names almost drop off the right side edge (something I didn’t notice on the 3D disc). Apart from that there’s nothing to complain about: Frankenweenie’s black and white is as dark and bright as each should be, with solid shades of gray not falling prone to any banding or crosstalk as could be feared.

Scratch Tracks:

In addition to the stunning picture quality, Frankenweenie sports a terrific soundtrack, from Elfman’s lushly recorded score to the various spot effects that the sound designers have fun with during the final pet resurrection stampede during the final reels. Everything is mixed well, leading me to suppose that the withdrawn approach to some of the voices is simply some kind of strange tonal choice, perhaps to suggest a more “realistic” performance reading but ultimately coming off as making their animated characters more disconnected from the vocals than anything. The fun here is in the rear channels’ directional effects, but demo moments are restricted toward the end of the movie: the rest of the film doesn’t really “scream” with memorable moments.

Final Cut:

It’s a well-known fact that pet dogs should never die in Hollywood movies and although Sparky doesn’t really end up “dead” it’s safe to say that this could have had an effect on parents taking their kids to see Frankenweenie in theaters. Another aspect might have been the black and white format: fine, for instance, when depicting the work of the “world’s worst director” in Ed Wood, a film made for cineastes to start with, but perhaps not so great in attracting families fed nowadays on shiny, colorful CGI, especially when your film is a stop-motion endeavor. Mostly, however, I just don’t think Tim Burton’s latest struck a hit with moviegoers because his original short, perfect as it was, doesn’t lend itself to being stretched out for a very padded 80 minutes.

Essentially there was too much repetition of past glories, too: nothing in Frankenweenie can match what has come before, and that includes the original featurette. That the original hasn’t been given a new HD transfer is a real shame – it does seem Disney elected to shove this out as quickly and cheaply as possible, evident from the all-zone ABC disc coding that will allow international fans to watch the disc where the film is still playing in theaters. Kicking into action only in its final act, Frankenweenie is a rare misfire from Burton, both a lazy collection and pale imitation of what he has done before. Disney’s disc matches the lackluster levels, but it’s such a shame that the first major home video release of 2013 turns out to be such a dud.

| ||

|