From LAIKA, the studio behind Coraline, comes another marvel of stop-motion animation and creative storytelling. For ParaNorman, LAIKA’s team of artists and animators built and brought to life a miniature town, a horde of zombies, and a quirky cast of characters to tell the tale of a boy with spooky talents who must save his hometown from a crisis of supernatural proportions.

From LAIKA, the studio behind Coraline, comes another marvel of stop-motion animation and creative storytelling. For ParaNorman, LAIKA’s team of artists and animators built and brought to life a miniature town, a horde of zombies, and a quirky cast of characters to tell the tale of a boy with spooky talents who must save his hometown from a crisis of supernatural proportions.

Chris Butler was the first spark as he’s the one who got the idea of that story and has been working on it for more than 10 years. He was head of story on Coraline and is the writer and director of ParaNorman. Sam Fell wrote and directed Dreamwork’s Flushed Away and Universal’s The Tale of Despereaux before directing ParaNorman.

Together, they also wrote the forewords of The Art and Making of ParaNorman, an intriguing book published by Chronicle, that reveals that, in that movie, art is not only in the medium, but also in the process. And that’s precisely what we talked about…

Animated Views: Today, filmmakers have access to so many art forms to express themselves, from hand-drawn animation to CG, live-action, different kinds of mixes, MoCap and more. Why was stop-motion the best art form to tell the story of Norman?

Chris Butler: When I first started writing it, the original idea was: wouldn’t it be cool to have a stop-motion zombie movie for kids? I think it has a lot to do with growing up on a diet of monster movies where the monsters were always stop-motioned. Ray Harryhausen’s creatures had a big influence on the tone of these movies. I remember seeing the skeleton fight in Jason and the Argonauts when I was a kid, and because of that I can’t imagine the undead moving any other way! So, it was kind of a nostalgic nod.

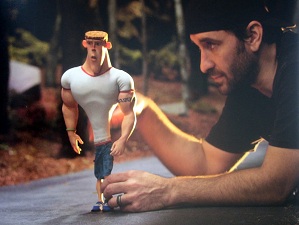

Sam Fell: Stop-motion is also about inanimate objects brought to live. It’s like dark magic. All the other forms of animation are representations of things. It would a the drawing of a zombie or a digital zombie. To have real zombies, we had to bring them to life! I love the irony in that.

AV: From Corpse Bride to Coraline, now ParaNorman and soon Frankenweenie, how do you explain that growing interest of the major studios and general audiences in stop-motion that we see today?

SF: I think it’s like anything in pop culture. We’ve grown because the generation’s grown. It used to be an underground thing for a smaller group, that group grows up, they get jobs, their own magazines, their own websites. They express their enthusiasm. I think there’s an amazing magic to this medium that won’t go away, that won’t lie down.

CB: Yes, and I think that audiences are increasingly sophisticated and they’re always reaching for something that kind of surprises them, something they’ve not seen before. I know stop-motion has been around for a long time but I think there’s an element of it where people are used to see CG. They’re savvy, they “expect” CG. Maybe there’s something in stop-motion that’s still a little unexpected and a little surprising. It’s still kind of amazing to see that it’s hand-made.

AV: Indeed. In ParaNorman, you have on one side traditional stop-motion, that goes back to Ray Harryhausen, and on the other side state-of-the-art 3D. And what I loved about your movie is that 3D is not used as a selling device, but really as a storytelling tool, as it allows us to see through Norman’s very eyes. Can you tell me more about that?

CB: I think one part of it comes from Coraline. Coraline was very well received for its use of 3D. The approach there was to make it immersive. Because stop-motion is a very tactile medium. You want to reach and touch these hand-crafted puppets. Because of that, Coraline invited audiences in to the screen rather than throwing things out at them. And it worked really well. It was really good-looking mariage of 3D stereo and stop-motion. So, partly, we wanted to maintain that sophistication. Obviously, this is a zombie movie, so we have a few jump-out moments, but that was partly it. We wanted to do it thoughtfully.

SF: As directors, we didn’t want to throw out all of our other tools. We didn’t want to forget about composition or depth of field. At times, we did things that weren’t officially correct for 3D for the sake of a proper dramatic use of the depth of field. Even in choosing a wide-screen format despite the 3D people said they needed more height.

AV: In The Art and Making of ParaNorman, Chris writes: “this book aims to illustrate the artistry in our medium, but also in our process. ” What do you mean?

CB: If you ever get the opportunity to walk around a stop-motion studio, you should because it’s kind of mind-blowing. It’s like walking around a sorcerer’s workshop. Because it’s a physical space full of an army of different kinds of craftspeople and artists. We have costume makers, prop makers, puppet maker, armature makers, carpenters, metal workers, all in one space. You realize it’s an eclectic group of very specialized artists. I think that’s something that needed to be presented in the book, but also to be enjoyed. When you walk around, you see desk spaces, sketches on the edge of pages of paper, and it’s all art. We didn’t want the art-of book to just about flat pieces of concept art. We wanted it to be about the whole process because there’s so much visually to enjoy in our studio.

AV: Chris, how is it for a story artist like you to see now his own story storyboarded by other artists?

CB: Because I was a story artist and because they had already worked on Coraline, it wasn’t that surprising. I was expecting people to take an idea and really run with it. That’s why I think we got some really funny physical comedy in the movie like the scene with Mr. Prenderghast’s corpse and Norman. When the storyboard artists told me about that, I really went for it! They really made the movie first and then we made it all over again.

SF: In the end, Chris and I were co-head of story. Because we had already talked between us about what we wanted the movie to be in some ways. The story was very well worked out, full of creativity. So, a lot of the work in our story room was toward addressing the cinematography and editing and the whole process of filmmaking. In other words, our job was to polish the story with our storymen.

AV: Chris, you said that there’s much of you in Norman. How was it to have someone – Kodi Smith McPhee – playing you?

CB: First off, yes, there’s a lot of me in Norman. Like him, I was an outcast. But what I was trying to do was to put a lot of any 11-year old in Norman. I thought about what is it to be 11. Going to school every day is hard because you just don’t know where you fit into the world. So, I think that on many levels Norman is an everyman, yet he’s unusual. Basically, Kodi Smith McPhee is a phenomenal actor. You know, Norman is a fairly complex character. He has to be smart, he has to carry the movie, but he also has to show some vulnerability and some comedy as well. Kodi was able to do all of that because he’s just a damn good actor!

AV: Can you tell me about John Goodman’s characterization of Mr. Prenderghast, Norman’s uncle?

SF: He’s amazing. He’s one of the great character actors, anyway. He voiced some great characters in animation. He ran through probably six different ways of being Mr. Prenderghast and that’s an amazing thing to see! He did the crazy Mr. Prenderghast, the doomed Mr. Prenderghast, the spooky ghost Mr. Prenderghast… He just gave funny different versions of Mr. Prenderghast. Besides, in ParaNorman, we were looking for a naturalism. So, we actually chopped up into cuts some of those “versions” of Mr. Prenderghast that we put together to give a kind of crazy up-and-down feeling. What a thrill to work with someone that cool, you know!

AV: Some artists of your crew come from that great animated film that is Secret of Kells. How’s that?

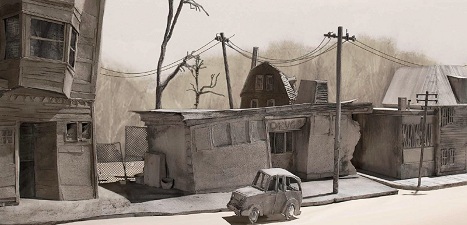

CB: It was the first step on a much, much longer process, actually. I’ve been drawing Coraline nearly for years, really. So, when finishing Coraline, the style of that movie was very much in my head and I wanted to get it out. Not that I didn’t like it – it’s beautiful. But I wanted to take a fresh perpective for ParaNorman and that involved looking at people that I hadn’t worked with before like The Secret of Kells guys. Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart were visiting the States and they came by the studio. So, I got the chance to meet them and got along very well with them. They were just happy to be involved and they just started throwing concept matters. It actually moved on a lot from there but what remains was -there a kind of organic, very illustrative line work that Ross does in a lot of his drawings. They were magical and there was something about them that very much matched the character design done by Heidi Smith.

I think Ross, our art director, was instrumental in finding that style but then the style became further developped by our production designer, Nelson Lowery, and the rest of the team. Nelson brought the different concepts together in the fim design.

AV: How did you come to Heidi Smith?

CB: She was actually straight out college as we were lecturing a bunch of portefolios from CalArts students. You always notice a trend in students’ work, especially the big universities like Cal Arts. That trend very much matches what’s going on in animation right now. Well, Heidi didn’t really have that. Her work didn’t have any familiarity with everyone else’s. It was just slightly rough and messy and very well observed.

SF: Chris had already been working with Heidi. Her designs were really challenging for puppets and it was a really good thing to have her with us.

AV: What about the animation style of ParaNorman, which is pretty different from what we’ve seen before?

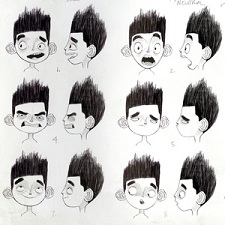

SF: We went for RP animation (“Replacement Face animation”). They had already used it on Coraline and we were really excited by that technique. The acting style in Coraline was quite broad in a way. Perhaps little figure gestures, a few in-betweens and a little more pose-to-pose. But in ParaNorman we wanted a more naturalistic style, more like a live-action movie. We had a lot more in-betweens and a lot more different types of expressions. Now, the 3-D Printer machine is quick enough so we can turn around ideas in a day. So, if we had a new idea for an expression, then we could turn that around and shoot it.

AV: One of the challenges of this movies was the mob scenes.

CB: From the start, we knew that we wanted to do things that hadn’t been done before or very difficult to do in stop-motion. We wanted to feel like it’s expansive, like it’s a big world, and often in stop-motion, it feels like it’s small-scaled. When you had a mob scene, it was like six puppets. Right from the start, we knew that we had some challenges, with a huge amount of background puppets. We actually had a separate team who worked on the background characters. And then, we very, very carefully worked on how they would appear on screen. We were just careful about making it feel like it was populated. And we also had the VFX department help us with digital background extras in the background of scenes and in wider shots, and they worked very closely with the puppet department to ensure that they were following the same design sensibilities.

AV: On the contrary, there are a lot of extreme close-ups in your movie, which is very rare in stop-motion, too.

SF: It was all possible thanks to RP and 3D printer for the faces. I’m glad you noticed because that’s exactly what it allowed us to do. Usually, in stop-motion, close-ups show head and shoulders whereas in live-action movies, you can see just the chin and the hair line. We wanted to do those live-action close-ups. Some of it is the printing that is much more detailed now. But it has to be said: it’s still a huge challenge to the animators to make the characters look alive. You know, Norman’s head is probably 3 inches in diameter. Throughout the movie, we pushed animators to new heights. The animation they produced is incredibly fine and nuanced. Everyone wanted to raise the bar.

AV: Precisely. ParaNorman is not only about action and humor, but also about emotion. What are your favorite moments in that regard?

CB: We specially made the Aggie story obviously the most heartbreaking moment because the whole movie rests on it, really. We wanted the make that emotional climax absolutely genuine, we wanted it to feel like real character people talking. It was true all the way through, from the writing to the vocal recordings and especially into the animation. We wanted to capture that real restraint and that real naturalism that would make it truly emotional and not just a caricature of emotion.

SF: The scene with Norman and his parents in the car is also a very touching and real scene. For that scene, we wanted the audience to get involved into the performance. The overall challenge was to make a coherent film. In order to achieve such moments, we couldn’t get too broad in matter of comedy. When we turned into those true, emotional scenes, we didn’t want to be coming from some completely broad cartoony place.

AV: How do you consider the role of the music in your movie and how did you work with composer Jon Brion?

CB: The music is vital. We alway knew that we wanted something a little bit different, as with almost everything else in the movie, it was a very early decision to try and aproach it in a way that we’re not used to seeing or hearing in contemporary animated movies. Jon Brion felt like a very natural choice, in a way. Quite early on, we had some rough storyboards come together for the opening of the movie and we just kind of put External Sunshine of the Spotless Mind on top of it. It just worked, and we kept it as a temp track during the whole process. So, when time came to discuss who we’d like to approach to do the score, it was a pretty easy decision to say “Jon Brion”. We knew he could handle kind of this slightly bittersweet, melancholic, indie vibe that we were after, that really encompasses Norman’s world. But then there was also the challence of referencing old 80s synth horror movie scores, but Jon is an aficionado of old, vintage instruments. So, it was an opportunity for him to play around in that world. I think what we got is completely unique.

AV: What memories will you keep from the experience?

CB: You always remember the moment of the first shot or the first test when the characters first come alive. In our case, it was the first time we saw the 3D color printer tests of Neil’s face, talking with all the freckles. We saw that in the theater of the studio. It was like “Wow”!

SF: Also, it’s the team, that family. As you know, an animated feature goes onto years. So, you develop a whole relationship with a whole bunch of new people. They’re unique, a very unique gang of people and they work very well together. It was a happy time, a harmonious production.

Our thanks to Chris Butler and Sam Fell, April Withney at Chronicle Books, Fumi Kitahara at PR Kitchen and Trina Dong at Focus Features!