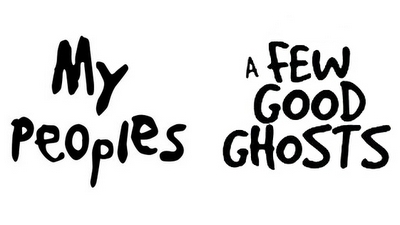

In 1999, director Barry Cook began working on an animated film which would merge hand-drawn and computer animation unlike any feature had ever done: My Peoples.

In 1999, director Barry Cook began working on an animated film which would merge hand-drawn and computer animation unlike any feature had ever done: My Peoples.

The film was based on his short story The Ghost & His Gift, a retelling of The Canterville Ghost. Furthermore, it was infused with Cook’s life, featuring much of the Appalachian music and folklore that had influenced him as a child. Thus, Cook worked with the Walt Disney Feature Animation studio in Florida to bring his vision to life.

For years, My Peoples underwent a variety of changes from storytelling to titles, in some cases due to shifts in Disney’s management. But Cook and the Florida crew pressed forward, believing with all their hearts they were working on a truly special film.

Finally, in late 2003, they screened part of My Peoples for then-Disney CEO Michael Eisner. Reportedly, he loved the footage, praising the feature as the studio’s next big hit.

No one could imagine that My Peoples would soon be canceled, and Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida would be closed – a time Cook could only describe as “heartbreaking.”

A few good ghosts of Christmas past, present and yet to come

To Barry Cook, it was not long ago when he was growing up in Goodlettsville, TN, just north of Nashville. At 10 years old, Cook already desired to be a filmmaker. With a Super 8 camera, Cook made his very first film: a three-minute, 20-second adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

“Because that’s how long the cartridge in Super 8 film ran – three minutes and 20 seconds,” explains Cook. “I edited the film right in the camera, one shot from the next.”

Cook gave himself the main role of Ebenezer Scrooge, while his mother and father, among other family members, played the Cratchit family. He and his little brother, Richard, also portrayed ghosts in the mini-movie.

“We even put a little phony tombstone in our front yard, where Scrooge broke down and changed his ways,” recalls Cook, laughing.

“I still have that film. I never had it transferred to DVD or anything. But it was the first movie I made. I was hooked.”

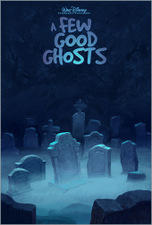

It wouldn’t be the last time a graveyard appeared in one of Cook’s films, as evidenced by

this concept artwork for A Few Good Ghosts. (Click to enlarge)

The monster in President Richard Nixon’s basement

Cook soon began experimenting with animation. He had always been drawn to illustrations, seeing as how his father was a painter. “The arts were really encouraged in my family,” says Cook. “Painting, sculpting and filmmaking – that was our lifestyle. It was sort of unusual amongst our neighbors and friends, but it was really great to have that background.”

At age 14, Cook created his very first animated film, The Saga of Benny Caru. In the short, the title character gets lost while searching for a men’s restroom in the White House, during Richard Nixon’s presidency. Ultimately, Caru ends up in the basement of the White House, where he discovers a creature very similar to Frankenstein’s monster. What happens next to Caru remains a mystery, even to Cook.

“So, the story ended with a monster coming at Benny. You could draw your own conclusion at the end,” remembers Cook. “I didn’t know much about story structure at the time.”

A smurfing start in animation

Cook’s love of animation was partially ignited by sitting in front of the television, as a four-year-old boy, enjoying the cartoons of Hanna-Barbera Studios. Hence, it seemed appropriate to him that, at age 18, his first break in the animation industry arrived with an internship at Hanna-Barbera, as an assistant animator. One of his most notable tasks there was working on the 15-minute pilot of The Smurfs, used to pitch the television series to NBC.

“I was just sort of an assembly line artist,” explains Cook. “I never got any credits on screen for those early things. But it was really good training.”

There’s just something special about small, blue creatures.

The rise of Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida

In 1981, Cook joined Disney after hearing a friend speak of the cutting edge technology soon to be introduced in TRON (1982). He served as an effects animator on the film, crediting the experience as when his career “took off, with a lot of bits and pieces in-between.” In his first role at Disney, Cook shared an office with fellow animator Mark Dindal, becoming an assistant animator under him. Both men aspired to direct animated features.

Cook went on to work as an effects animator for films such as The Black Cauldron (1985), Disney World’s Captain EO (1986), Oliver & Company (1988) and The Little Mermaid (1989).

Both Oliver and Mermaid fared well enough at the box office that Disney’s senior vice-president of animation, Peter Schneider, announced the company would release an animated feature each year. With revitalized interest in the medium, Disney launched The Magic Of Disney Animation, housing Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida, at Disney-MGM Studios in May 1989, the same year Cook transferred from Burbank to Orlando. Behind massive windows inside the 15,000-square-foot building, Walt Disney World visitors could watch as Cook and about 70 other Disney animators worked on scenes sent from Disney’s main animation studio in Burbank, starting with The Rescuers Down Under (1990).

Roy Disney officiates the opening of Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida in 1989,

joined by Ward Kimball (right), Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas on stage.

In front of the stage, Mark Henn observes Oliver & Company‘s Dodger, beside

Barry Temple and Dave Stephan. (Click to enlarge)

Off His Rockers

The Florida studio’s chance to shine came with their own short but high-profile project: the Roger Rabbit vehicle Roller Coaster Rabbit (1990). Having worked with the Burbank studio on the wacky rabbit’s first short, Tummy Trouble (1989), Rob Minkoff returned to the director’s chair, with Cook assisting on the special effects.

After their regular workday had ended, Cook and the Florida crew were engaged in an experimental short, Off His Rockers, which told the story of a toy rocking horse longing for the attention of his videogame-obsessed boy. The twist was that the boy would be the only traditionally-animated character in an otherwise computer animated world. Cook assumed Off His Rockers, at best, might be shown at a computer animation trade show. Upon seeing the short, however, Disney execs scheduled it to play in front of the 1992 re-release of Pinocchio. Then director Randal Kleiser saw Off His Rockers and asked for it to play in front of his film, Honey, I Blew Up The Kid, a request granted by Walt Disney Studios Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg.

With the impressive Off His Rockers on its resume, WDFA Florida was given room for expansion, more than doubling its staff to 180 employees. It continued providing animation for Burbank features Beauty & The Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992) and The Lion King (1994).

Meanwhile, Cook landed the director’s gig on the next Roger Rabbit short, Trail Mix-Up, which had its theatrical run in front of A Far Off Place (1993). Another short, Hare In My Soup, was canceled after relations soured between Disney and Steven Spielberg’s production shingle, Amblin Entertainment. Despite his involvement in two of the previous three Roger Rabbit shorts, Cook “was not involved” with Soup.

Artwork from the abandoned Roger Rabbit short, Hare in my Soup (Click to enlarge)

Mulan

Instead, Cook was involved with something bigger – much bigger – for WDFA Florida: its first full-length feature. Disney execs saw fitting that the Florida studio should craft the 36th entry in the company’s official animation canon.

Given the positive reception to his short films, Cook was selected to direct the film, its tentative titles including The Legend Of Mulan, The Legend Of Fa Mulan and Legend Of A Warrior. Certain aspects of the film had to be completed at the Walt Disney Feature Animation headquarters in Burbank, given the Florida studio’s infancy in feature-length productions. Hence, Cook returned to Burbank for two years, while character animator Tony Bancroft joined the project as a co-director in Florida just as storyboarding commenced. In January 1995, work commenced on Mulan, budgeted around $90 million.

In June 1999, Mulan opened in theaters nationwide as Disney’s best-reviewed animated film since The Lion King. Furthermore, it domestically outgrossed Disney’s previous canon entries, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1996) and Hercules (1997). That same year, WDFA Florida expanded to about 400 artists in a new $70 million, 200,000-square-foot, four-story animation building.

“A great way to spend your life”

But Mulan had taken its toll on Cook, having worked tirelessly on the film for a five-year stretch, almost exactly to the day it began. “I was the first person who would start developing the movie, and I was literally the last person to leave the Technicolor lab after the final color timing.” Worn, Cook began to question his future in the animation industry.

As Disney began to release Mulan internationally, Cook visited Studio Ghibli, where he met its co-founder, Hayao Miyazaki. But Cook had a personal confession for the master Japanese animator and director. “I told him, ‘I’m really burned out,'” recalls Cook. Miyazaki offered an encouraging response: “Stick with it. Animation is a great way to spend your life.”

Months later, Cook and Bancroft scored an Annie Award for their direction on Mulan, while the film itself claimed Outstanding Achievement in an Animated Theatrical Feature.

Barry Cook and Tony Bancroft’s cameo in Mulan

Cook learned Disney was considering a direct-to-video sequel to Mulan. He wrote a one-page synopsis in which protagonists Mulan and Shang, soon to be married, receive word from The Emperor that strange things are happening up north. The synopsis ended with the ghostly ancestors of Mulan in an epic battle against the deceased army of the villainous Shan-Yu.

But Cook was never involved beyond submitting the idea. “[I] guess Disney had something else in mind,” he says. Instead, Disney planned two sequels to Mulan. The second sequel would ultimately be canceled due to a lack of interest, despite the involvement of original Mulan screenwriters Raymond Singer and Eugenia Bostwick-Singer.

“Too human” for animation

After a five-month sabbatical, Cook began developing ideas for his next animated feature. The one that “stuck” was based on a short story he had developed years earlier: The Ghost & His Gift, a retelling of Oscar Wilde’s The Canterville Ghost. Set in the late 1940s Appalachia, Gift told how a ghost and three children helped bring together a young man and the girl he loved.

Cook pitched The Ghost & His Gift to Disney CEO Michael Eisner and Thomas Schumacher, who had replaced Schneider in early 2000 as the president of Walt Disney Feature Animation. Eisner and Schumacher agreed the pitch showed promise, yet they passed on sending the feature into production. Eisner was reportedly deterred by the simplicity of The Ghost & His Gift, believing the story needed additional conflict. Schumacher, on the other hand, had a different reason for rejecting the idea as an animated film: it was “too human.” In other words, The Ghost & His Gift could just as easily be done in live-action, due to its cast of humans.

“You can agree or disagree,” says Cook, “but that was sort of the thought of the studio – the characters probably shouldn’t be able to be brought to the screen in a live-action film.”

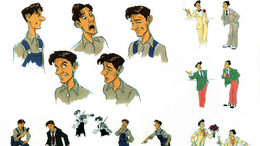

Young lovers Elgin Harper and Rose McGee (Click to enlarge)

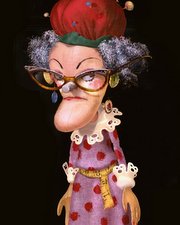

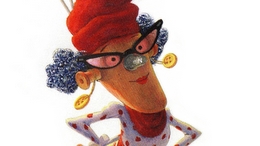

Cook immediately began to reconstruct his idea. Observing the story’s setting, he studied elements of the Appalachian culture. One that particularly fascinated him was that of folk art dolls. Isolated artists and musicians in the Appalachian Mountains, a generation or two removed from Cook, had crafted the marionette-type puppets out of quirky wood carvings and random items which would have otherwise been discarded as trash. In fact, Cook’s own grandmother had tried her hand at creating folk art dolls.

“I was fascinated by the idea, ‘What if these types of characters came to life?,'” says Cook. “They were the key to unlocking potential for a story set in that region.”

Thus, My Peoples was born.

My Peoples

Cook knew he had to do something special to capture Schumacher’s attention and persuade him to greenlight My Peoples. He shipped an old wooden violin case to L.A. through FedEx and instructed an assistant to place it on a conference room table. Via teleconference, Schumacher entered the meeting, although Eisner was unable to attend. Cook, still in Florida, began to pitch his revised idea.

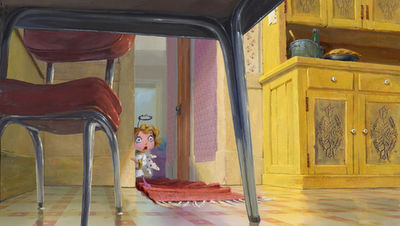

The director told the story of Elgin Harper, a young man who makes the folk art doll Angel out of a flour scoop as a gift to woo Rose McGee. Unfortunately for Elgin, Rose happens to be from a family feuding with his own. Nonetheless, the young man decides no feud can quench his love, determining to deliver Angel to Rose. But a spell from Rose’s father, Old Man McGee, backfires, bringing Angel to life. And Angel, as it turns out, does not want to do her job; she has no desire to be a gift of love or an “olive branch” between the families. With a will of her own and a bad attitude, Angel refuses to fulfill her purpose and embarks to leave town.

Schumacher was intrigued by the synopsis. Then came the instructions he had been anticipating. “Open the violin case,” Cook said.

A maquette of Angel lay perfectly inside, “almost like it was a little casket.”

Cook created this maquette of Angel to help get

My Peoples greenlighted. (Click to enlarge)

“They were quite enamored with the nice visual prop they could hold and pass around the table,” says Cook. “From that moment on, the enthusiasm was pretty high. People thought, ‘This could be really special.'”

But Cook had one more item to impress the execs. Thinking back to Off His Rockers, Cook proposed making My Peoples with 70 percent computer animation and 30 percent hand-drawn animation. While the folk art dolls would be computer animated, the human characters would be traditionally animated. “I didn’t want the latest plastic CG look, since at that time, computer animation had sort of a simple look. You couldn’t get past certain things,” says Cook. “So, we created a hybrid look for the film.”

As a result of the presentation, My Peoples was greenlighted with a budget of $45 million, a conservative number given that most of Disney’s traditionally animated films cost closer to $100 million. The budget was reasonable due to the film’s blend of animation styles, although Cook did not have that benefit in mind when selecting the hybrid. “It was always an artistic choice on my part,” he says. “I like trying to mix those two mediums, first and foremost.”

How to make an Angel from a flour scoop (Click to enlarge)

Animated cast, animated characters

There was another benefit to the animation hybrid. With My Peoples, the animators of WDFA Florida could animate traditionally, while also training to someday complete a fully-computer animated feature. For example, the respected Alex Kupershmidt, best known for animating the title character in Aladdin, would get his start in computer animation, while traditionally animating Old Man McGee.

A crew containing some of Disney’s best talent assembled for My Peoples, working from a screenplay by Ian Southwood. Ric Sluiter re-teamed with Cook, once again serving as art director after filling the role on Off His Rockers and Mulan. Fresh off his Annie win for Mulan, Hans Bacher signed on as production designer. Kendra Haaland acted as producer, taking a team of artists to the Folk Art Center in Kentucky and the Huntington Museum of Art in West Virginia to study the work of the late folk artist Charles Kinney. Dean Wellins, a supervising animator for The Iron Giant, was named Head of Story. Meanwhile, Andreas Deja, who had gained much acclaim as supervising animator for classic Disney villains Gaston, Jafar and Scar, remained in Burbank as the animator of Rose McGee.

Andreas Deja’s early sketches for Rose McGee (Click to enlarge)

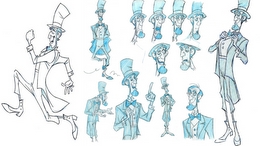

Together, these individuals and many others worked to bring My Peoples to life. Knowing a movie is only as strong as its characters, Cook developed a slew of hilarious folk art dolls to appear alongside Angel. For instance, Ms. Spinster was carved from the wooden leg of Elgin’s deceased aunt. Made from a tree stump, Crazy Ray lived in a hole under a front porch. Playing a steel guitar made from a sardine can, Blues Man was constructed from a broken mandolin, while Cherokee Boy was made from a worn work glove. Good O’ Boy was a mechanical redneck made from old car parts, bearing more than a passing resemblance in personality to what would become Mater from Pixar’s Cars (2006).

Not all of the characters would make it to the final draft of the story, though, as Disney execs worried the over-the-top Preacher Man, a Southern Holiness character, might be seen as an offensive stereotype.

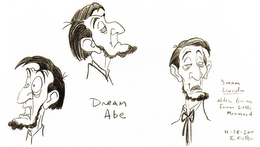

Cook was particularly excited about taking advantage of the fact that folk art creators often modeled dolls after famous individuals. He crafted a version of Abraham Lincoln unlike anyone had ever seen, with a scrub brush body and spoons for ears. The folk art doll Lincoln was convinced he was the actual 16th President of the United States, performing duties similar to those of the real Honest Abe. But Cook clarifies that a certain oft-rumored joke, in which the folk art doll emancipates chickens in the barnyard, never made it past the suggestion point. It was “an idea that someone pitched to me,” he explains. “But I always felt that it was borderline racist, and I did not approve of it.”

The folk art dolls of My Peoples assemble. (Click to enlarge)

Cook fondly looks back on the characters, believing audiences would have embraced them. “They were really quirky and very individualistic, with these characters basically having to go on a mission together,” he says. “I felt like it was a very divergent group of characters, having to get along on a unified mission to bring two lovers together.”

Of course, Cook needed the right voice cast to breathe life into the characters. As the buzz on My Peoples spread throughout the animation community, the mainstream media picked up on the vocal cast rumored to include Dolly Parton (Angel), Lily Tomlin (Ms. Spinster), Hal Holbrook (Abraham Lincoln), Travis Tritt (Elgin Harper), Ashley Judd (Rose McGee), Charles Durning (Old Man Mcgee), Lou Rawls (Blues Man), Mike Snider (Good O’ Boy), Jean Smart (Arvilla Tugthistle), Diedrich Bader (Herbert Hollingshead) and Billy Connolly (Angel’s dog).

President Bill Clinton’s lead strategist James Carville had even agreed to voice Crazy Ray. Disney would later deny Carville’s involvement, as reports suggested studio execs were concerned about his lack of voice acting as well as the potential controversy from the political pundit’s involvement.

Cook remains mostly silent about the voice cast. “I’m probably not at liberty to discuss their involvement to a great degree, because that’s up to them,” he says. But Cook admits that, of the actors listed, “we definitely talked to them and wanted them to be part of the film.”

The human characters of My Peoples pose together for this image dated July 22, 2002. (Click to enlarge)

Oh bluegrass, where art thou?

The director desired to fill My Peoples with music common to Appalachian culture, especially being a fan of the music himself. But he knew that most studio heads would be hesitant to approve a bluegrass soundtrack, especially for a tentpole animated feature.

“I’m sort of a bluegrass fanatic,” says Cook, an avid fiddle player. “Bluegrass is such an odd bird, in a way. There’s a lot of good bluegrass music in the West Coast, but it’s very isolated in pockets of small communities of players. It’s certainly a niche market.”

During the early stages of My Peoples‘ development, the entertainment industry was blown away by the runaway success of a Coen brothers’ film – or more accurately, the film’s soundtrack. While O Brother, Where Art Thou? earned a respectable $71 million domestically, its soundtrack went on to become certified eight times Platinum and won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 2002, close to when My Peoples officially entered production.

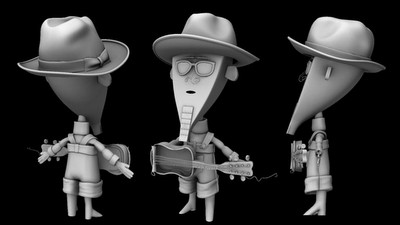

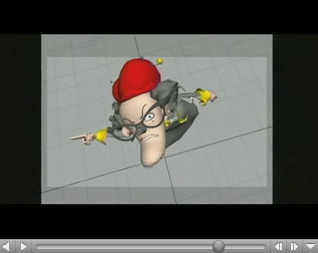

Blues Man in a CGI model by Mick Todd (Click to enlarge)

“After it came out, at least the studio executives in Hollywood understood what bluegrass music was and the power and the appeal of it, and how it can work in storytelling,” explains Cook. “In a way, that film opened the door to make the development of My Peoples possible. Otherwise, I think the executives would have still been scratching their heads and asking, ‘What is this?'”

To capture the music of Appalachia, Cook enlisted Grammy-winning bluegrass and country artists. Executive music producer and consultant Ricky Skaggs penned three songs – one in collaboration with Marty Stuart, who also provided some of his own tunes. Skaggs also collaborated with Hank Williams III to revitalize a classic Hank Williams Sr. song for My Peoples. Rumors suggested Parton, Judd, Tritt and Rawls would perform in the film.

“It was a dream cast of people to put together musically,” says Cook.

Cook considered asking Mark O’Connor to compose the fiddle-infused score of My Peoples. Although the Grammy winner had never composed a film score, Cook was confident the former child prodigy was up to the challenge. As the most-sought session one fiddle player in Nashville, O’Connor had already transitioned into writing concertos and symphonies.

“He was someone I always thought had the right sensibility if he wanted to get into movie scoring,” says Cook. “It’s a little bit of a different animal. But he certainly had everything I felt it would take to make something really unusual, because he understands the roots of the Appalachian music.

Roger Borelli’s CGI model for Cherokee is brought to life. (Click to enlarge)

“He had written some classically-composed stuff that kept the rich sound of the fiddle and the ancient sound from Appalachia. I felt, of any musician in the world, he understood how to elevate that simple music to a big place that could be a movie score.”

But Cook would never ask O’Connor to score My Peoples. The film would never reach that stage of development.

Montagues and Capulets vs. Hatfields and McCoys

While WDFA Florida progressed on My Peoples, the Burbank studio began development in 2002 on its own feature about lovers amidst two feuding families, the Montagues and the Capulets. Inspired by Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Gnome Story told of a garden gnome, tired of being stuck in the dirt, and his quest to woo a female figurine, eager to break free from her sheltered life in a china cabinet. Beauty & The Beast helmer Gary Trousdale signed on to direct a screenplay by Rob Sprackling and John Smith (Chicken Run), with revisions by Andy Riley and Kevin Cecil of Robbie The Reindeer fame. Oscar-winning duo Elton John and Tim Rice began writing music for Gnome Story, as John’s Rocket Pictures was co-producing the film with Disney. Scheduled for a 2006 release, Gnome Story – soon retitled Gnomeo & Juliet – would feature computer animated characters interacting in a live-action world.

Some people began to question if Walt Disney Feature Animation really needed two movies about lovers in feuding families, featuring computer animation hybrids and starring usually-inanimate objects that come to life.

“Yeah, I think that could have been one consideration,” says Cook. “It’s likely there was some concern at the studio.”

The Harpers and the McGees of My Peoples, seen here in early concept art,

were based on real-life feuding families the Hatfields and the McCoys. (Click to enlarge)

Still, he believes the similarities between Gnomeo and My Peoples were limited beyond the surface, calling his film “at least twice removed” from Shakespeare’s tale. For example, My Peoples was based more on the historical family feud of the Hatfields and the McCoys – or the Harpers and the McGees, as Cook named them out of respect to their real-life doppelgangers. But the director admits, “One reason the story of the Hatfields and the McCoys has had such longevity is not only that it was a true-life feud, but also because it has so many similarities to a Romeo & Juliet type of story. It sort of has the classical elements.”

Alien invasion preludes Disney exec’s resignation

Cook hoped those “classical elements” of My Peoples would translate into Disney’s next masterpiece. Since 2000, the Burbank studio had delivered films which fell short of expectations from critics and audiences, including Trousdale and Kirk Wise’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001). But the Florida studio had a surprise hit in the making: Lilo & Stitch, directed by Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois. In June 2002, the critically-acclaimed tale of a girl and her pet alien opened with more than $35 million, missing the top box office spot by less than $500,000 behind Steven Spielberg’s Tom Cruise-starrer Minority Report. Lilo & Stitch became a breakout success for Disney, collecting $273 million worldwide and a Best Animated Feature Oscar nomination. The film was followed by a television series and three direct-to-video sequels.

Still, Eisner could not overlook that Lilo & Stitch was one exception in a line of disappointments. Furthermore, he observed that as audiences dismissed the studio’s traditionally-animated efforts, they were flocking to see the computer animated films of Pixar Animation Studios, Blue Sky Studios and DreamWorks Animation. Disney’s theatrical animation department, often hailed as the cornerstone of the company, was no longer the leader in the industry. Eisner believed changes needed to be made, including a key managerial role.

In October 2002, Thomas Schumacher announced he would be leaving Walt Disney Feature Animation.

In 2000, Michael Eisner (left), Thomas Schumacher, Peter Schneider

and Robert Iger attend the L.A. opening of the Lion King stage show.

“Tom was a great encouragement for me, for My Peoples,” recalls Cook. “But then he left to go to Broadway, and some of the projects he had been championing, including My Peoples, didn’t get as much support, studio-wise.

“I guess that’s probably the easiest way to put it.”

“2D is dead”

On October 25, 2002, Disney executed its first round of clean-up animation firings. The case for hand-drawn Disney animation was about to get much worse. On Thanksgiving weekend, the Burbank studio’s Treasure Planet, budgeted at $140 million, opened with a mere $12 million. The film ended its theatrical run with only $38 million domestically and $109.5 million worldwide.

Back at WDFA Florida, Aaron Blaise and Robert Walker were directing the traditionally-animated Bears, set to open April 2004. With a tight schedule, the animators continued to make excellent progress on the picture, set to be the first feature-length venture crafted 100 percent at the Florida facility. Early buzz on Bears was excellent, with insiders suggesting it could capture the spirit of The Lion King.

Brother Bear concept artwork

But Blaise and Walker were shocked when, in December 2002, Disney revealed it had switched the release dates for Home On The Range and Bears. To coincide with The Lion King‘s Platinum Edition DVD release, the latter would open in November 2003, reducing its schedule by roughly five months.

And with Eisner’s new mantra that “2D is dead,” Home On The Range would be Walt Disney Feature Animation’s final hand-drawn feature.

A Rose McGee by any other name…

In January 2003, David Stainton of Walt Disney Television Animation took command as president of Feature Animation. Suddenly, the future became uncertain for some of the films Schumacher had greenlighted during his tenure.

My Peoples was about to undergo considerable changes, one of them being its title. Cook had adopted the title due to “my peoples” being the collective name a deceased folk artist had given his folk art puppets. Of course, the phrase was also a welcoming reference to one’s family, the importance of which was a strong theme in the film. If nothing else, Cook discovered that the title created intrigue among even his co-workers.

“When someone at the studio first heard the title My Peoples, they came to me and said, ‘Is this like a story about Moses? You know, ‘let my people go,’ or something?'” remembers Cook. “I said, ‘No…’

“I think Disney just thought it was an odd title,” he continues. “I don’t even know all the other titles it got. But it wasn’t unusual for different titles to be kicked around.”

Angel investigates the scene, in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

The tale of star-crossed lovers would be renamed Once In A Blue Moon by January 2003. In February, Stainton and Eisner viewed a story reel for the film, which resulted in the project being pulled back for retooling. By May 2003, Once In A Blue Moon had evolved into Elgin’s People. Despite its story still being in development, Stainton placed the film into production that summer, around the same time that Disney laid off 50 animators in Orlando.

Concurrently, Blaise and Walker’s Bears, retitled Brother Bear, was near the final stages of completion. But the summer of 2003 would prove a disappointing one for traditional animation enthusiasts. During the Independence Day weekend, DreamWorks Animation’s Sinbad: Legend Of The Seven Seas opened in sixth place with $6.8 million, one of the worst debuts ever for a major animated film. After Sinbad and Treasure Planet, Disney execs wondered if a similar fate lay in store for Brother Bear. To avoid the competition of The Matrix Revolutions and Elf, Disney rescheduled Brother Bear to open on November 1. Analysts and fans alike were shocked, since the date was a Saturday. Disney responded that it did not want to open a family film on October 31, where it would have to compete with trick-or-treating on Halloween.

Crazy Ray takes the train, in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

By the end of July, Elgin’s People was re-titled Angel & Her No Good Sister, as Stainton reasoned the new title suggested instant conflict. Cook continued working hard on the picture, with a summer 2005 release in mind. But he could not help but notice a certain DisneyToon Studios traditionally-animated feature finally in development, also set for a 2005 release: Mulan II. While Walt Disney Feature Animation’s efforts had drawn mixed results at the box office, the company’s direct-to-video sequels were profitable, thanks to being animated overseas with lower budgets. But even they were not inescapable from Disney’s transition to computer animation. Walt Disney Animation France had closed in 2002, laying off 103 employees. Concurrently, the company had just announced Walt Disney Animation Japan, with its staff of 89, would shut its doors in 2004. Throughout all its animation divisions, Disney had slashed more than 700 jobs and reduced animators’ salaries by 30-to-50 percent, within two years.

“We saw the dominoes falling,” says Cook. “It all happened very quickly.”

A Few Good Ghosts

WDFA Florida pressed forward on My Peoples. “We got to the point where we actually had some test animation and some experimental frames,” says Cook. “We were looking pretty good there, toward the end.” But reports indicated that Stainton believed the hand-drawn humans were not meshing with the computer animated world. “I don’t think we had gone far enough down that road to prove it one way or the other,” recalls Cook. “Whether Stainton thought the hybrid was poor or successful, I really can’t say because I never got that specific feedback.” Nonetheless, Cook admits he would have complied if the studio had mandated the film be entirely computer animated.

With a head made from a clothespin, Angel’s dog bares his painted-on

teeth in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

By October 2003, Disney had settled on a final title for the film: A Few Good Ghosts. Its folk art characters had shifted from being merely enchanted to being inhabited by ancestral spirits. For instance, Elgin’s deceased relative Edna Lee would inhabit Ms. Spinster, while his Uncle Ned would take on the folk doll form of Abe Lincoln. A young Native American boy named Little Feather would become Cherokee Boy. Cook found inspiration for this shift after he and his crew enjoyed an art direction trip in the Appalachians, where ghost stories were rampant.

“Almost every hotel we stayed in, or every person we visited, had ghost stories,” says Cook. “‘Room 203 is a haunted room! So, whichever one of you guys got that room, watch out tonight! You might hear a noise or something!’ It felt like a part of the culture. That’s why I embraced and tried to make the idea work.”

Cook considered that perhaps the deceased ancestors of Elgin Harper could inhabit the folk art dolls, bringing them to life. “The dolls were ‘possessed,’ although we always stayed away from that word,” he recalls. “It did turn the story a little differently and make it more of a Halloween tale.

“But ultimately, I don’t feel it was really the right thing for the story.”

The title treatment for My Peoples and A Few Good Ghosts

Indeed, Stainton was allegedly one of the brains behind the new ghost-centric storyline, seizing an opportunity to take advantage of the trick-or-treat holiday. However, Cook is quick to dismiss the belief that all of the story changes should be credited to Stainton.

“When you’re developing something, it’s not always a mandate from the studio. You sit around, and you talk about it.” says Cook. “Certain ideas seem like good ideas at one time, but maybe they aren’t as good as you once thought. But you tried things out, and your intention was really great.

“If you’re in the right position to develop a story, you can keep working until you find the right angle on it. Sometimes it’s a luxury; sometimes it’s a downfall. After all, you can get into these circular conversations that never really end, and things don’t get decided as well they should, perhaps.”

One movie sabotaged, another saved

Cook could not shake the belief that A Few Good Ghosts needed to return to the sweet simplicity of My Peoples. To him, My Peoples was the heart of what the movie should be: how a folk artist uses his art to get the girl he loves. “As an artist, I have a connection with that story – a story about an artist and his artwork ‘coming to life,'” he explains. “That was the core of the story, more than what made the characters come to life or that they were based on his ancestors.”

But Cook understood that being a director in animation required being a team player, at least given the circumstances. That meant listening to and considering each story and joke suggestion, particularly the ones from Eisner and Stainton. Cook believed, though, that they only had the film’s best interest in mind, trying to make a crowd-pleasing hit. Plus, he was thankful that at least the project was still his own, as Disney execs had not suggested adding an assistant director.

Elgin’s folk art dolls go to the movies in a pivotal scene from My Peoples. (Click to enlarge)

“A lot of people ask me, ‘How can you possibly direct a movie when there is so much studio voice in the movie and so many people weighing in on it?’ The answer is, I never qualify an idea by whom it came from,” says Cook. “I didn’t care if an idea came from Michael Eisner or a custodian emptying the trash after work, who just said, ‘I like this character pinned on your wall!’ To me, the source of the idea wasn’t important; it was the quality of the idea.

“As a director, your job is to listen to those ideas and then choose the ones that really fit your vision for the story. If there’s a downfall, it is maybe not choosing the best suggestions. Or maybe not fighting hard enough for my own ideas.”

One of the biggest changes in the film was the setting for one pivotal scene in which the folk art dolls must sabotage Rose McGee’s date with Herbert Hollingshead. Originally set in an in-door theater, the setting was changed to a drive-in theater, taking advantage of the late 1940s time period. To stop the courtship, the character Good O’ Boy, being a master at mechanics, tapped into the speaker box hanging from the couple’s car window. He and his folk art comrades were then able to dub the voices in the drive-in movie to be far less romantic. Rose and her man watched the screen in utter confusion as the dubbed voices effectively reworked the plot of the drive-in movie to kill the romantic mood.

Abe and Cherokee must sabotage a date between Rose McGee and Herbert Hollingshead,

in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

“It was hilarious!” recalls Cook. “It was a side-splitting, laugh-out-loud moment; it was just beautiful! That was one of my favorite scenes. I’ve always loved that scene, the way the whole thing played out.

“I really felt, with that scene, we’d cracked the code on the movie.”

“You folks finally have a movie here!”

There was even more good news for the Florida studio: Brother Bear was a hit. Despite opening on a Saturday, the film collected $19 million. If it had opened one day earlier, Brother Bear would have claimed the top spot at the box office that weekend. Instead, it came in second to Dimension Films’ Scary Movie 3. Some analysts suggested Disney had tried to set up Brother Bear for failure by opening it on a Saturday, to compete with a highly-anticipated film from its then-sister studio. If Brother Bear had failed, they said, the closing of the traditional animation studios would seem more justified.

“I don’t buy into conspiracy theories,” responds Cook.

Besides, Cook had his own film on which to focus. Around early November 2003, Eisner sat down to view a rough version of the first act of A Few Good Ghosts. The film’s crew anxiously waited to hear the CEO’s verdict. Finally, Eisner turned to them and reportedly praised, “You folks finally have a movie here!”

A Few Good Ghosts had come a long way from My Peoples,

as this concept artwork displays. (Click to enlarge)

A week later, Stainton and veteran WDFA Florida producer Pam Coats viewed the footage, expressing similar acclaim afterward. Allegedly, one executive even went as far as to compare A Few Good Ghosts‘ quality to that of the best Pixar films.

“It had great potential as a comedy,” explains Cook. “I wouldn’t call it a romantic comedy; I would call it more of a comedy with a romantic subplot, with a lot of adventure. The characters were very small creatures in a strange world – or very strange creatures in a real world.”

Cook and his team of artists were thrilled to see A Few Good Ghosts finally coming together. However, tourists at Walt Disney World could no longer see the animators’ smiling faces. The Magic Of Disney Animation exhibit was in the midst of a seven-week refurbishment. As with Disney California Adventure’s Disney Animation attraction, the Florida-based exhibit would now give visitors a general understanding of the animation process. It would not, however, give them a real-life, behind-the-scenes look at the animators of WDFA Florida.

A big announcement

On November 14, 2003, Stainton surprised WDFA Florida employees as he entered the building that Friday morning. Individuals there and in Burbank believed Stainton had flown to New York City the prior afternoon, to meet with Disney Theatrical about future projects. But there he was in Florida, ready with an announcement.

Angel spies an unpleasant surprise in the kitchen, in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

Stainton, Coats and Senior Vice President Andrew Millstein called a meeting with the studio employees. Some staffers worried, while others wondered if the news might be a reward for the studio’s track record at the box office.

Soon Stainton stood before the crowd and delivered the news: A Few Good Ghosts would be canceled immediately, and more than 100 people would be let go in two months.

“That moment in my career was absolutely heartbreaking,” recalls Cook. “More than any other project, I poured my soul into it. I opened myself up to all the things I love. The culture I grew up in, the music that I still, to this day, love dearly – it was all part of that. It was very personal for me as a filmmaker.”

In an email to employees at the Burbank headquarters, Stainton further explained the cancellation of A Few Good Ghosts: “The fundamental idea is not strong enough or universally appealing enough to support the kind of performance our movies must have today.”

Cook understood that not all projects at Walt Disney Feature Animation reach completion. But he thought, surely, given the amount of time and resources already used on A Few Good Ghosts, the film would reach theaters. After all, Disney had not long ago moved forward on the troubled Kingdom Of The Sun, despite its inflated budget, allowing Mark Dindal to rework that flick into The Emperor’s New Groove (2000). Instead, A Few Good Ghosts would join legendary canceled films like Don Quixote and Chanticleer in Disney animation history.

The train stops for Cherokee, in Ric Sluiter’s concept painting. (Click to enlarge)

“Maybe I made some bad choices in some of the ways that, in the later development stages, I wanted to turn the film,” says Cook. “But at the same time, Disney was undergoing a lot of cutbacks. When they started closing studios, we were fighting to keep the film alive – and the studio alive. Once you’re making the film under those circumstances, it’s really an impossible situation to be successful.”

The sky falls

After the cancellation, Cook and his creative team returned to calling A Few Good Ghosts by its original name, My Peoples. Eventually, he learned the main reason it had been canceled. Disney execs had seen the sky falling – and the sky was traditional animation. “For us, it came down basically to Mark Dindal’s Chicken Little or My Peoples. One was going to get made, but not both,” explains Cook. “The decision was made. Mark’s film won out.”

For Stainton, the decision was fairly easy. One was an old-fashioned, partially hand-drawn picture infused with bluegrass, edgy humor and a 1940s setting; the other was a computer animated, pop culture-referencing action comedy about a chicken fighting space aliens.

“There were high aspirations,” says Cook of his film. “It was very unusual for a Disney project – maybe so unusual that it was too colloquial of a certain cut, not broad enough in its appeal. But, for me, I’ve always wanted to tell stories that are very specific to their world.”

Preacher Man and Angel watch as Cherokee ponders on the porch, in Hans Bacher’s artwork. (Click to enlarge)

Despite his project being canceled in favor of Dindal’s, Cook harbored no ill will against his former officemate. “I have nothing against Mark,” says Cook. “He’s been a great friend for a long time, and he’s a very talented director.”

Besides, Cook knew Dindal could certainly relate to some of his recent experiences. For instance, Dindal had to rework his original idea for Chicken Little, which once involved a female version of the title character being forced to attend Camp Yes-U-Can after the infamous “sky is falling” debacle.

The future of Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida

Cook believed WDFA Florida could continue, with or without his film. “I never really connected the closing of the studio with the cancellation [of My Peoples],” says Cook. “Other projects could have been made there. It was a very viable – dare I say fantastic – studio with an amazing group of artists.”

WDFA Florida wanted to continue Disney’s legacy of traditional animation. After all, it was the studio behind the animated short John Henry (2000), in which the title character blazed ahead in a race against the technologically-advanced steam-power hammer, using only the old-fashioned hammer in his hands. Similarly, WDFA Florida wished to counteract the competition’s CGI products with classic hand-drawn storytelling, in addition to its own lineup of computer animated entries. Already, preliminary work had begun on the traditionally animated Selkies, in which a fairy learns to love a lord after he steals the enchanted seal skin she uses to disguise herself from humans.

My Peoples concept artwork (Click to enlarge)

Some of the animators thought WDFA Florida could at least still provide animation for the Burbank studio’s and DisneyToon Studios’ films, similar to what it had done in its early years. But Stainton encouraged animators to find other employment, although he would not confirm the closing of WDFA Florida.

That is, until he entered the studio on January 12.

“[I] don’t remember much about the big announcement,” says Cook. “It was my worst day in 22 years at Disney, that’s for sure.

“My most fond memory of that sad time was Sam Ewing stating, ‘There’s no business like show business.'”

Ultimately, Stainton and Eisner desired a return to the 1980s model of Walt Disney Feature Animation, with its talent working together in the same building. That building would be in Burbank rather than Orlando.

My Peoples concept artwork (Click to enlarge)

People began to question if Disney execs had simply used A Few Good Ghosts as “busy work” for the studio. After all, some claimed the company had decided to close WDFA Florida as early as summer 2002. But Cook disagreed with the theory that his personal project had been used as a distraction for the animators.

“With a big decision like [the studio’s closing], it has to be worked out where everything is in place to make it happen, whether it’s a positive or a negative decision,” says Cook. “On a personal level, if there was some animator who wasn’t working out on a project, you might know three weeks ahead of the person that he or she is going to be let go. But you can’t tell him or her the minute you make the decision. From the proper meetings to the HR department, everything has to be in place.

“Closing down the Florida studio was no small operation. So, obviously, the company would certainly know before we knew,” he continues. “But the idea that we were just doing busy work or anything like that, I don’t really feel like it was ever that way. I don’t think it was devious or plotting or scheming on anybody’s part. The company had some tough business decisions to make at that time. So, the studio here in Florida was sacrificed at that expense. I don’t think it was anything deliberately or intentionally diabolical.”

WDFA Florida employees reunite with former studio head Max Howard

at the Orlando Film Festival in November 2009.

As WDFA Florida employees cleared their desks to leave, they received an email from Stainton, congratulating them on the studio’s Oscar nomination. Brother Bear had been named one of the three films in the running for Best Animated Feature at the 76th Annual Academy Awards. For 258 Central Floridians, however, the nomination could only be described as bittersweet.

On March 19, 2004, Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida closed its doors forever.

Left behind in Florida

Stainton had informed WDFA Florida that “core people” would be offered opportunities at the Burbank studio. Indeed, Disney offered 50 employees, from tech people to supervisors, one-year positions without job security and moving expenses. Chris Sanders, Alex Kuperschmidt and Aaron Blaise were among those offered contracts in Burbank.

Cook, on the other hand, “was not offered a position to remain.”

Instead, Cook joined the other animators looking for work. For one of his first post-Disney moves, he turned to screenwriting. Cook found the process therapeutic, whether it allowed him to artistically express frustrations or spread humor.

My Peoples director Barry Cook

During downtime on My Peoples, Cook had honed his writing skills with Skunk Ape, based on the Southern states’ – particularly Florida’s – version of Bigfoot. “I thought it lent itself to a kooky, low-budget, live-action comedy along the lines of Adam Sandler’s The Waterboy,” recalls Cook. Animator Trey Finney had presented the idea to Disney in one of the studio’s “gong show” story pitch sessions. Ultimately, Disney would never use Cook’s screenplay. But Cook admits that Skunk Ape, being his first solo attempt at a screenplay, “wasn’t brilliant – but it was funny.”

Thus, after WDFA Florida’s closing, Cook penned The Cat & The Fiddle, taking only its name from the famous nursery rhyme. “It is intended to be an animated feature,” says Cook. “I have not shopped it around at all.” To help develop such projects, Cook formed Studio PB&J, LLC in 2004 as his own limited liability company. “I lend out my services through it,” he explains. “It’s not a production entity, but some of my original development ideas and scripts are held within.”

New Beginnings

Meanwhile, Disney opened its editorial department and archives, allowing animators to update their reels to find future employment. Pixar, DreamWorks, Industrial Light & Magic and the now-defunct C.O.R.E. Digital Pictures of Canada immediately sent recruiters to Orlando. Former WDFA Florida animators also flocked to small local studios such as Genesis Orlando and Raven Animation. Some animators even formed their own animation houses. Eddie Pittman founded Legacy Animation with a mission to produce only traditional animation. My Peoples animator Tom Bancroft and Rob Corley hurried plans to add an animation division to their comic book company Funnypages Productions. Mulan co-director Tony Bancroft announced Toonacious Family Entertainment in June 2004.

A screenshot from Legacy Animation’s unfinished animated short, Lucky

One of the most heavily-publicized animation houses to arise out of WDFA Florida’s closing was Project Firefly Animation Studios. Under president Dominic Carola, the Universal Studios Florida-based venture was to deliver traditional and computer animation, its building decorated with posters of WDFA Florida’s films. While Cook did not consider joining Project Firefly, he and Carola would become good friends over the years.

Project Firefly supplied significant animation work on Universal’s Curious George (2006). In an interesting “twist,” the studio also took on subcontracting work from Disney, which included Cinderella III: A Twist In Time (2007), Pooh’s Heffalump Halloween Movie (2005) and, ironically, Brother Bear 2 (2006).

In fact, Disney had been looking to independent studios for many of its traditional animation needs. At one point, Walt Disney Imagineers had asked Feature Animation to animate a segment for the Stitch’s Great Escape attraction at Disneyland’s Tommorowland. But since the company had already let go most of the animators who worked on Lilo & Stitch, it was unable to replicate the film’s distinctive style. Thus, the project had to be outsourced to Renegade Animation.

By 2008, most of the noted animated studios had closed. Legacy ended five months after it began, due to the exit of a major investor. But at least it was a quiet death compared to that of Genesis Orlando, which became entangled in controversy and lawsuits after investors and character co-creator Beryl “Woody” Woodman claimed they were not paid for the computer animated Tugger: The Jeep 4×4 Who Wanted To Fly (2006). Meanwhile, Project Firefly had quietly moved off the Universal lot in 2007.

Project Firefly animators (left to right) Paulo Alvarado, Dominic Carola, Gregg Azzopardi, John Webber and Glen Gagnon

Bridges rebuilt

Amidst those troubling reports, animators carefully watched as major shakeups occurred at Disney. In November 2003, Roy E. Disney had resigned as chairman of Feature Animation and as vice chairman of the board of directors, citing Eisner’s handling of the animation transition as a major reason. Shortly afterward, he launched the “Save Disney” campaign, which ultimately led to the Disney shareholders declining to re-elect Eisner to the corporate board of directors. In September 2005, Eisner resigned as CEO. His successor, Robert Iger, rebuilt Disney’s relationship with Pixar, announcing the purchase of the Emeryville studio in January 2006. Days later, Stainton announced his resignation. Subsequently, Iger appointed Pixar’s John Lasseter as the chief creative officer of Pixar and Disney Feature Animation, the latter being renamed Walt Disney Animation Studios.

In July 2006, Disney announced a brand-new traditionally animated feature: The Frog Princess, to be helmed by Little Mermaid directors Ron Clements and John Musker. By its December 2009 release, however, the tale of Maddy the chambermaid would become that of Tiana the restaurant server, under the new title The Princess And The Frog.

Cook in the kitchens

Also in 2006, Cook signed with IDT Entertainment to develop the animated Mean Margaret. Screenwriters Joe Piscatella and Craig Williams adapted Tor Seidler’s critically-acclaimed book about the title missing girl who befriends woodchucks Fred and Phoebe. In August 2006, Liberty Media, owner of the Starz cable network, purchased IDT Entertainment, renaming it Starz Media. Ninety days later, all of their feature animation development was put on hold.

Carter Goodrich’s concept artwork for Mean Margaret (Click to see more)

Hence, Cook moved to Animation Lab, spending the summer of 2007 in Jerusalem. He supervised an international group of story artists for The Wild Bunch, the first feature-length computer animated film produced in Israel. Mulan screenwriter Philip LaZebnik penned the comedic story of a rag-tag group of common wildflowers and plants who must battle an evil army of genetically-modified cornstalks to save their meadow. Scheduled for a U.S. release in 2012, The Wild Bunch features the voices of Abigail Breslin, Willem Dafoe, Chris Klein, Elizabeth Hurley and Willie Nelson.

In 2008, Cook joined Laika Entertainment to direct its computer animated Coraline follow-up, Jack & Ben, reuniting with art director Ric Sluiter. The previous year, Laika had removed the film’s original writer and director, Jorgen Klubein, after the project had been in pre-production since 2005. Written by David Skelly, Jack & Ben portrayed two bluebird brothers who enter a dangerous road-rally race, based on the real-life Gumball Rally, on their migration route to Florida. But in a move somewhat familiar to the director, Laika announced the layoff of 65 employees and the cancellation of Jack & Ben, less than a year after Cook had signed onto the project. The studio had decided to discontinue their computer animated slate, concentrating instead on stop-motion films such as the upcoming ParaNorman.

Bob Foster’s storyboard for Jack & Ben (Click to see more)

Afterward, Cook turned his attention toward Japan, where anime house Studio 4ºC had animated segments of The Animatrix (2003) and Batman: Gotham Knight (2008). In collaboration with Campus Crusade for Christ, Cook penned a screenplay for My Last Day (2011), revealing Jesus’ crucifixion through the eyes of a thief crucified beside him. Cook also storyboarded a version of the disciple Peter’s denial of Jesus. According to Irvin Klaschus of The Jesus Film Project, Cook wrote seven synopses of follow-ups to My Last Day, each portraying Jesus’ crucifixion through the perspective of someone close to Him.

Arthur Christmas

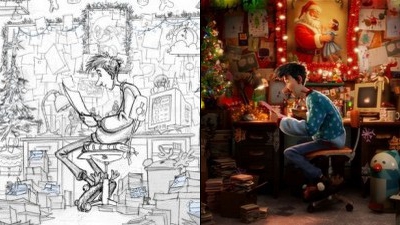

In February 2009, Cook signed with Aardman Animations for a year-and-a-half stint on the computer animated Arthur Christmas. Written by co-director Sarah Smith and Pete Baynham, the film portrays the title character’s attempt to complete a high-tech mission on Christmas Eve.

“The reason I was brought onto the film was that Sarah had done a lot of work in television, mostly live-action,” explains Cook. “So, I was there to help along with the animation, from designing the film and its characters to all of the storyboarding process.”

Bjorn-Erik Aschim’s illustration was the starting point for animators to create

the title character’s office in Arthur Christmas.

Once the reels were storyboarded and the characters designed, Cook and his Aardman team made the “big hand-over” to Sony Imageworks. Cook received a co-director credit on Arthur Christmas, although early marketing materials for the November 2011 release would fail to indicate it. Nevertheless, he greatly enjoyed his time with Aardman, believing the end result to be a quality film.

“I think it will be a great Christmas movie for years and years and years to come,” he says. “I mean, it’s classic, but it’s quirky and has great in-depth characters.

For Cook, the “creative, fun environment” at Aardman was reminiscent of the years he spent at WDFA Florida. “I would mark it up as a really great experience, working with Aardman,” he says. “You wonder how you could even be part of that culture. To be invited into that studio and work there was really sort of a dream come true.

“I felt like I was a really good fit there.”

Walking With Dinosaurs

For his latest feature, Cook has teamed with Animal Logic, Evergreen Films and BBC Earth to adapt the latter’s Walking With Dinosaurs television miniseries for the big screen.

“We’re shooting live-action for it and finishing story reels on it,” explains Cook. “Of course, since there are no living dinosaurs, all the characters are animated. But it will be a pretty unusual and amazing film.”

Last September, a press conference in Amsterdam revealed James Cameron and Vince Pace’s Cameron-Pace Group 3D camera system could play a role in Walking With Dinosaurs, scheduled to be released December 2013. (That certification of the film’s 3D is currently pending.) Even with all the technical wizardry, however, producers knew the film needed a compelling story. For that, they looked to Cook. “It’s a little different from my sensibility as a storyteller,” he says. “I was brought in as a storyteller because they already had the nature aspect.”

Early promotional licensing image for Walking With Dinosaurs

As for Animal Logic, Cook believes the studio can apply the same photorealism to dinosaurs as it did with the penguins in Happy Feet and the owls in Legend Of The Guardians: The Owls Of Ga’Hoole. “These dinosaurs are going to look as good as those owls, still trying to keep it very true to life,” says Cook. “It’s like we took cameras back millions of years ago, to film these creatures. It’s a big challenge.”

Spending time at the Sidney-based Animal Logic has been a reunion of sorts for the director. Some of its artists are former story artists from DisneyToon Studios, helping to explain its vibe similar to that of another Disney studio – one which Cook formerly called home.

Let My Peoples go (back into production)

Sometimes Cook wonders if the future is not over for My Peoples, the rights of which Disney still owns. Since the cancellation of WDFA Florida, Disney has revamped much of its development slate. Chris Sanders’ American Dog became Byron Howard and Chris Williams’ Bolt, while Glen Keane’s Rapunzel Unbraided became Nathan Greno and Howard’s Tangled. Sam Levine and Jared Stern’s Joe Jump became Rich Moore’s Wreck-It Ralph, while Mike Gabriel’s The Snow Queen became Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee’s Frozen. With those projects in mind, Cook understands the possibility that My Peoples could easily be resurrected – but without him.

“It could definitely be a great film if somebody wanted to make it or at least some version of it; it could probably be pretty successful,” says Cook. “But it wouldn’t be the version I would make, certainly.”

Angel helps Crazy Ray break free from his prison ball and chain,

in this My Peoples concept artwork. (Click to enlarge)

With that in mind, Cook would still love to make My Peoples. “If I ever get the call from Disney, saying, ‘We’re thinking about giving this thing another look,’ I would be interested,” he confirms. “If I now had the chance to make the movie myself, I think I could turn it into what I’ve always imagined it would be. Under the right studio leadership, it would make all the difference in the world, perhaps.”

“I love the film more than any project I’ve ever worked on. I feel like I left a lot of myself behind in it.”

Life lesson learned

But Cook bears no “sour grapes” about the past, attributing to himself part of the blame as to why My Peoples never materialized. “I feel like I can never take myself out of the equation of the movie not getting made,” he explains. “You can’t say, ‘Oh, these guys didn’t know what they had!’ It’s just not true, because you have to take your part in the whole thing.

“As I’ve often said, failure is always an option. Anything you do that’s worth putting yourself out there, there’s always a risk of it not working out.”

Nonetheless, Cook looks to the experience as a “big life lesson” learned. “It has made me a stronger director, a stronger filmmaker and a stronger person,” he says. “In retrospect, as hard as it was to go through, I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in right now, had the movie gotten made. The position I find myself in right now is a good one. I’m happy with the work I’m doing.”

But every now and then, Cook puts on Ricky Skaggs’ Brand New Strings album, on which the tracks Appalachian Joy and Monroe Dancin’ – written for My Peoples – offer a brief glimpse of what might have been. Then he sits back and remembers the people of Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida. Cook will never forget the love and support he found for more than a decade there.

The animators of Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida in spring 1991 (Click to enlarge)

“It was a great group of artists, who have gone on to do great things,” says Cook. “It was a fantastic studio, with the esprit de corps of the artists. Everybody had a lot of respect for one another. Removed in California, it was hard for studio execs to really understand or see that. But we felt we had something very special.

“We were a family of animators, supportive of each other in a tremendous environment.”

Concept Artwork Gallery (Click to view)

Rune Bennicke

Assorted Images

Storyboard Gallery (Click to view)

Videos (Click to view)

More information about My Peoples may be found in the following books:

Hans Bacher’s Dream Worlds: Production Design for Animation

Charles Solomon’s Disney Lost and Found