With six films, director Simon Wells has garnered more experience than most directors would collect with twice as many projects. From filmmaking to screenwriting, he has captivated audiences with live-action as well as traditional, computer, and motion capture animation.

Born in Cambridge, England, Wells studied audio-visual design at the De Montfort University. Upon graduating, he directed commercials at Richard Williams’ animation studio. Soon Wells was approached about being the supervising animator for an innovative comedy directed by Robert Zemeckis: Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). His professional relationship with Zemeckis further developed while doing storyboard and design work for both Back to the Future sequels (1989-90).

After the closing of Richard Williams Studio, Wells moved to Steven Spielberg’s Amblimation, where he directed An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story (1993), and Balto (1995). Unfortunately, Amblimation was likewise shut down. Wells, in addition to much of Amblimation’s talent, flocked to DreamWorks Animation. Not only was he a story artist for the studio’s first picture, Antz (1998), he also co-directed its first traditionally animated film, The Prince of Egypt (1998). For their direction on Egypt, Wells, Brenda Chapman, and Steve Hickner were nominated for the prestigious Annie Award.

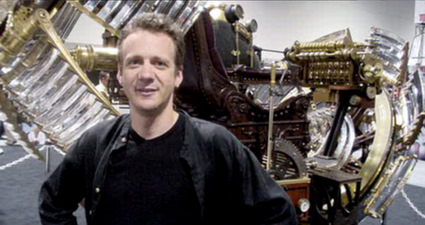

Director Simon Wells travels to 2002 on his “time machine”.

Having succeeded in animation, Wells decided to try his hand at directing a live-action feature. For this effort, he chose The Time Machine (2002), an adaptation of the classic 1895 novel by his great-grandfather H. G. Wells. The director later discovered the project to be too ambitious for a director new to live-action filmmaking. As a result, Wells was relieved by fellow filmmaker Gore Verbinski for the remaining 18 days of shooting. Nonetheless, he returned to complete post-production on Time Machine. Wells then went back to DreamWorks Animation, where he continued as a story artist for films such as Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002), Shrek 2 (2004), Madagascar (2005) and Flushed Away (2006).

In 2007, Wells received an intriguing offer from an old friend. Robert Zemeckis’ ImageMovers Digital had recently been purchased by The Walt Disney Company. Responsible for hits like The Polar Express (2004) and Monster House (2006), the motion capture shop was eager to start a new slate of films. Concurrently, Disney had optioned the feature rights to Berkeley Breathed’s critically-acclaimed illustrated book Mars Needs Moms. Courtesy of Zemeckis, Wells was offered the chance to direct Mars, as the second feature from the new ImageMovers.

In November 2009, ImageMovers’ first Disney picture, A Christmas Carol, opened to a mixed reception. At the box office, it collected $137.9 million domestically and $325.3 million worldwide. While the totals were not small, they failed to meet Disney’s expectations. On March 12, 2010, Disney announced they were closing ImageMovers. Wells’ Mars Needs Moms would be the studio’s final film.

Simon Wells and wife Wendy at the Mars Needs Moms Hollywood premiere

On March 11, 2011, Mars hit theaters. Opening to mixed reviews, the film faced another sci-fi adventure, Sony’s Battle: Los Angeles, and gathered $6.9 million. By the end of its theatrical run, Mars had taken a mere $39 million worldwide. However, the story was not over for ImageMovers. In August, Zemeckis revealed ImageMovers was moving its images to Universal Studios, where he made his directorial debut with I Wanna Hold Your Hand in 1978.

As for Wells, he currently resides in Los Angeles with his wife, Wendy, and daughters Meredith and Teagan. Disappointed but not defeated by Mars’ performance, he reminisces about the talented crew which brought the film to life. Perhaps Mars will finally find its audience via Blu-ray and DVD. But no matter the film’s future, the genial Wells remains optimistic about his own future, whether it is with DreamWorks Animation or ImageMovers 3.0.

Animated Views: How did you become the director and screenwriter of Mars Needs Moms?

Simon Wells: Basically, Bob Zemeckis called me up and asked, “Hey, are you interested in making one of these films?” I said, “Yeah – if my wife and I can write it.” He said, “Okay.” [laughs] One of those strange moments that shouldn’t happen in Hollywood but do.

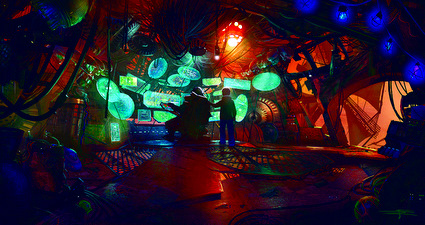

Early concept painting of Gribble’s lair – Click to enlarge!

AV: I believe, originally, you pitched two very different versions of the project to him.

SW: Yeah. The original book by Berkeley Breathed is a very, very small book. We had to pitch an idea of how that was going to expand to an 85-minute movie, so we went in and did a full-on pitch of a “little kids” movie. Bob went, “Eh, not really interested in that.” We thought, “Oh, okay. All right.” So we thought out a completely different storyline, and we went back with that. He went, “Eh, you know, I don’t want all this detail. I just want a basic idea. Imagine you were meeting an actor at a party, and you really wanted to convince this actor you want him in your film. Tell me the three-minute pitch.” We had accumulated a couple hundred pictures off the internet, of inspirational visuals, and went in with literally a 10- or 11-bullet-point pitch. Bob just said, “Yeah, I like that movie!” and shook our hands, and we did it.

AV: When co-writing the film with Wendy, how did the husband-and-wife process work?

SW: We’ve been married for 23 years; we had been married for 20 years by the time we started on the film. The truth is, we’ve got a good way of arguing about stuff; we’ve got that sorted out. When we have script discussions, there are three to five rules of how to go about having those heated or otherwise discussions. It worked pretty well.

AV: Making this project even more of a family affair, Mars Needs Moms was partially inspired by your great grandfather, H. G. Wells.

SW: There’s a semi-quote at the beginning of the book, as I recall. The opening page has, “Across the gulf of space, critters messy and unmothered regarded this planet with envious eyes and slowly but surely drew their plans for a visit,” which is a paraphrasing of [H. G. Wells’] War of the Worlds.

The Milo of Berkeley Breathed’s classic

vs. the Milo of Simon Wells’ adaptation

AV: Speaking of the book, the art direction in it is quite different from the more realistic look of the film.

SW: Part of that is the automatic sensibilities of Doug Chiang, our production designer, and his whole crew. He has a vast gang of incredibly talented artists who all came together under Doug, after doing design work on things like the Star Wars movies. They were just itching to do a science fiction movie. Basically, this design crew had done stuff for Bob on his previous movies Polar Express, Beowulf, and A Christmas Carol. They really wanted to do sci-fi stuff – robots, space ships, and stuff like that. A lot of it had to with the natural sensibilities of the group of artists we had developing the film.

There was also a push from Bob, saying, “Let’s make the world realistic so that when we go to Mars, we’ll know what we’re seeing is real, as opposed to making the whole thing sort of a cartoon in style.”

AV: As a director, it’s been nine years since your last film, The Time Machine, and roughly 13 years since your last animated film, The Prince of Egypt.

SW: Right, but you’ve got to bear in mind Mars was three years in the making. We started writing back in October 2007. So it wasn’t that long, actually. [laughs]

AV: Good point. Still, you’ve had a respectable track record. What led to your taking a break?

SW: The Time Machine was a really tough film. It was a much bigger film than I had anticipated. I knew it was big, but I hadn’t been aware of how draining it was going to be. That made it a not entirely pleasant experience. I’m pretty happy with the way the movie came out in the end. But it was tough; it didn’t help that it was my first live-action film. I was learning on the job – on a film that kept changing to essentially a different film. We start off in the 19th century, and we keep jumping about into one thing or another. Just when you were comfortable shooting in one environment, you changed to another environment and were shooting something completely different.

Simon Wells in front of his “time machine”

at the 2001 San Diego Comic Con

I think also, if I’m absolutely honest, there was stuff that really wasn’t as satisfying about the story as it should have been. I was aware of that, while shooting, but unable to do anything about it. Actually, what was really good about The Time Machine, it made me realize, “I have to stop and learn how to write, because simply directing stuff other people are writing isn’t an experience that’s really fulfilling.”

I’m aware that I’m not fully equipped to direct unless I’m also capable of writing. Wendy and I, who have written a few scripts together previously, just said, “You know what, let’s actually settle down and take a certain amount of time to learn how to write.” You can only do it by writing reams and reams of stuff. Every screenwriter you talk to says, “You have to write 10 bad scripts before you start writing a good one.” So we said, “Let’s start writing! Let’s get those 10 bad scripts written!” [laughs] You can read them if you like. Some of them are really bad.

AV: They can’t be worse than some of the stuff I’ve written.

SW: [laughs]

AV: In the late ’90s, weren’t you going to direct a live-action sequel to Casper?

SW: Yeah, I was involved with developing the script, as a director working with writers. Eventually, Amblin concluded they just didn’t feel there was enough interest to make the movie. I also don’t think they could secure the star of the first one, Christina Ricci, who was a very big element of what made the first one work so well. Plus, there had been a couple of direct-to-video films. The general feeling was, unless Casper 2 just lept off the page, it wasn’t going to be worth making.

AV: So those direct-to-video Casper films…

SW: They kind of took the edge off it, I think. I’ve never seen them. In fairness, I don’t know what they’re like. But I think the feeling was, if they were being released direct-to-video, a certain amount of luster had already come off the franchise.

(L-R) Wendy Wells, Simon Wells, Seth Green, Jodie Breathed,

Berkeley Breathed, Mindy Sterling, and Jack Rapke

AV: I see. Many people have yet to accept motion capture films. Because of this, did you have any hesitation in working on Mars Needs Moms?

SW: No, I was fascinated by the technology. It’s interesting. I think there are more people in professional criticism who have a problem with motion capture than the general audience. I think there’s a large section of the general audience who really can’t tell. Also, the thing that is a little painful is, yes, there are bits of Mars Needs Moms that do look motion captured, but there is an awful lot of it that doesn’t. I think the animators at ImageMovers did an extraordinary job and really got on board with a level of caricature that I was trying to bring. The majority of the work in the film, I feel, really lives extraordinarily well. The trouble is, particularly with some of the early scenes, maybe a few of those are a little rougher because they were early in the process. I think that got the heckles out of some people straight away.

The thing is, it’s getting better and better all the time. Look at the early color movies. They didn’t look very realistic either; they were flooded with light, and the color process gave a very strange hue. It definitely wasn’t like reality. There were a lot of people back then who were saying, “This is an abomination! Black-and-white film is so beautiful, why are we doing this? We’re ruining the beautiful lighting you can do with black-and-white films. You have to just completely blanket these color films, and they look dreadful!” With all new technology, there’s going to be a number of movies that break ground. People didn’t have a problem with the motion capture technology in Avatar. We’ll see how well Tintin is received. I haven’t seen it yet, but I gather the motion capture in Rise of the Planet of the Apes is very good.

AV: How did you feel when you heard ImageMovers Digital would be closed, and your film would be its last?

SW: Disappointed. It was a really terrific group of artists, and they were tremendously dedicated to the film. Thank God they were, because if you are aware you are working yourself out of a job, there isn’t really an incentive to get your scenes done on time. But the guys there worked really hard. Actually, every department finished ahead of schedule and under budget, because they were that dedicated to the film. Very few people left early. Some people had job offers. One of the supervising animators came to me and said, “I’m really sorry, but I’ve got this offer.” I said, “Take it! You’ve got a mortgage; you’ve got kids. Take the job. Yes, you’re leaving a month early. But you’ve got a life to lead.”

The cast and crew of Mars Needs Moms – Click to enlarge!

(Center L-R) Simon Wells, Wendy Wells, and Jack Rapke

(Middle Row L-R) Seth Green, Joan Cusack, Elisabeth Harnois, and Dan Fogler

Any time a studio closes, it’s a sad thing. (I’d been around Amblimation in London, which closed down after three movies.) It’s a film business; it’s not a business Disney decided they wanted to be in anymore. That was probably due to a management change. But you can’t blame them for the choice they made. Starting an animation studio, it’s very difficult to be hitting them out of the park from the get-go. But that’s a business choice. When this actually happened, I went and gave a talk at the studio. I said, “Look, back when I was in my late twenties, I was working on Who Framed Roger Rabbit at a studio in Camden. That studio was closed down. They didn’t continue the studio and make more movies there. They just shut it down, because they didn’t want to be running a studio in London anymore. It had nothing to do with the quality of the movie we made; it was just a business decision.”

AV: But what is next for you? Do you think you’ll stay with Disney, or go back to DreamWorks Animation? I know Zemeckis is also taking ImageMovers to Universal.

SW: All these things. I actually had a good working relationship with the guys at Disney. Despite what was a slightly awkward political situation, I got along well with Sean Bailey and those guys and would very happily work with them again. In fairness I think, given that Mars didn’t perform very well, it’s a little difficult for them to offer me another film right now.

Jeffrey Katzenberg and DreamWorks have always been incredibly kind to me. I’m actually talking to you from my office at DreamWorks; it has remained here, strangely, through my leaving to do Time Machine, working on Polar Express for a year, and going off for three years on Mars. I’m back in the same office. Jeffrey welcomed me back with open arms. I have a great deal of loyalty to Jeffrey in particular and DreamWorks in general. They have always been very kind to me. I’m looking at possibilities of doing things here. I’m actually helping out; I’m doing a bunch of writing and storyboard stuff for a couple of projects here.

Dan Fogler (Gribble) with director Simon Wells

But we’re also talking to Zemeckis’ company about another project. We just sent them the latest script we’ve written. But are they in the position to produce for other people? Perhaps they are now. So, yeah, we’re talking them. You have to go out and get friendly with as many people as you can. So we’re meeting all over town, looking for projects.

Walt Disney Studios’ Mars Needs Moms

is now available to own on Blu-ray