Walt Disney Studios (2007-2009), Buena Vista Home Entertainment (November 30 2010), three single discs with supplements, 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen, Dolby Digital, all rated PG, Retail: each sold separately at $29.99

Storyboard:

Three distinct periods in Walt Disney Studios’ history are examined in a trio of excellent documentary feature films.

The Sweatbox Review:

For those lamenting that it seems we have seen the end of the brilliant Walt Disney Treasures releases, Disney has pulled off a pretty good trick by announcing, instead, the home video release of three widely publicised but limitedly shown theatrical documentary films, concurrently released with yet a further documentary, on the making of the recent short film Destino, with a sparkling new Blu-ray edition of Fantasia.

If you’re the kind of casual Disney fan that enjoyed the broader Treasures releases, such as the classic character cartoon compilations and the various shorts and specials, then I share your disappointment that no further collections of their like look to be coming any time soon. You’re likely to view these new releases as nothing more than bonus features and as such I urge you to move on: there’s nothing for you here.

But…if you’re the kind of aficionado that lapped up every peek behind the scenes, every Walt-hosted show and every slice of rarely seen television material or Disneyland park footage, then you’ll truly, like me, be absolutely wallowing with excitement in your element! And, far from missing out on our annual dose of Disney history from the archives, these three releases – all of them theatrical feature documentaries – fill the gap (tin packaging notwithstanding) very, very nicely and provide some Treasure-tastic magic of their own.

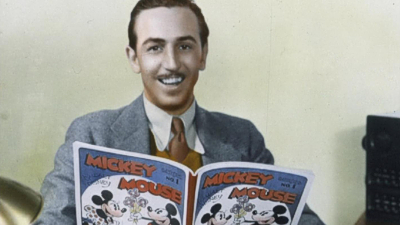

Disney has always thankfully been very astute in preserving its own heritage, and with good reason: more than any other film production company in movie history, audiences all over the world have not only been interested in the films the Studio makes, but in how they make them. Walt was quick to pick up on that, documenting each production and retaining every last scrap of film or concept imagery, and whatever large sums of money must be spent in storing these artefacts is surely a fraction of the priceless riches this now hugely vast archive of material can provide to researchers, or producers of documentary subjects.

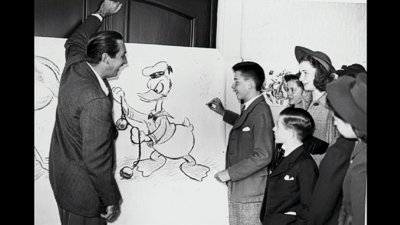

Documentaries have always been a part of the Disney Studio’s legacy. Even before Snow White premiered in 1937, Walt had put together a reel showcasing how animation at the Studio was produced. Originally meant only for exhibitors’ eyes, public interest led to a more generalized edition, How Walt Disney Cartoons Are Made, one year later, and the entertaining “tour” of the Studio circa 1941 in the Studio’s first live-action film The Reluctant Dragon. In the 1950s, factual programming was a staple of the weekly Disney television show, and various documentaries revealed the workings of Walt’s films (reconstructions for the camera or not), such as perhaps the most famous of them, Tricks Of Our Trade (1957).

In 1981, promoting both Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston’s animation bible The Illusion Of Life and the then-upcoming release of The Fox And The Hound, 1960s Disney star Hayley Mills returned to the Studio to host a two-part feature-length documentary on the Studio’s achievements and its latest film, in a wonderfully serious examination of the artists’ craft that I would dearly love to see released on home video. In 1988, the UK’s prestigious arts program The South Bank Show offered more of the same with The Art Of Walt Disney, an intelligent appraisal of Walt’s philosophy and the modern day, after the new regime of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg had revived its fortunes.

Soon after, something interesting began to happen: those that had been involved and played enormously important roles in the creation of Disney’s films, but perhaps never been given tremendous recognition, began to have the spotlight turned on them. Walt’s original right-hand man Ub Iwerks’ granddaughter, Leslie, wrote a book and directed a feature-length documentary on her grandfather, The Hand Behind The Mouse, which finally gave Iwerks the public credit he deserved. Soon afterwards, Frank Thomas’ son Theodore painted a simply wonderful and affectionate portrait of his Dad and artistic partner Ollie Johnston, Frank And Ollie (1995), with Walt’s daughter Diane Disney-Miller providing much the same kind of intimate portrayal of her Dad for Walt: The Man Behind The Myth (2001).

That film was the work of The Walt Disney Family Foundation, an organization established by Disney-Miller to preserve the memory of her father as a human being, mostly concerning Walt the man and not the head of a global conglomerate. Over the years, the Disney Foundation, Leslie Iwerks and Ted Thomas, and now the Sherman Brothers’ sons, have all continued to document aspects of the Disney Company’s history, and further documentaries have included The Pixar Story, The Age Of Believing: The Live-Action Disney Classics, Dalí & Disney, which accompanies the Destino short with Fantasia, and the three new feature films discussed below…

Walt & El Grupo (2007, 107 mins)

Our journey through Disney history begins, appropriately enough, with the man himself, who found himself in a unique situation, and a victim of his own success. With the popularity of Snow White, Walt Disney Productions had expanded, moving from the old Hyperion Studio to a new, custom built, state of the art complex which took away some of the intimacy that Walt and his artists had been able to share previously. By 1942, this had also led to rises in activities amongst some of the staff that Walt was not privy to, including the wish of some to unionize the Studio in keeping with what was going on elsewhere in Hollywood.

As the documentary opens, we find Walt feeling betrayed by these people, whom he thought he had treated fairly and rewarded generously. At the same time, far away from the world of entertainment, the growing threat of oppression from Nazi Germany was on the increase in South America and, although the US had not entered World War II at this stage, they were obviously keen not to let this menace spread in their neighboring countries. A plan was devised to promote one of the most popular exponents of American entertainment to those countries, in a “Good Will” tour that would promote the Good Neighbor Policy between north and south divides, hopefully leading, if and when the time came, to an allied dispersing of the dark forces.

Walt, who did not wish to go on a publicity tour, accepted the trip as a way for his artists to gather material for new animated subjects, the results of which were the eventual features Saludos Amigos (1943) and The Three Caballeros (1945) and a plethora of short subjects, including their own documentary of the trip, South Of The Border With Disney (perhaps the best release of all this material is still the 1990s deluxe Exclusive Archive Collection boxed edition LaserDisc). But Walt & El Grupo doesn’t carry a “The Untold Adventures” subtitle on its poster for nothing: although devotees will know about the trip and will have seen the resulting films, those were produced purely with that “good will” in mind, typically Disneyfied to promote unison between countries.

The real story, as delved into in this film, reveals the other side of the camera like never before, with a startling amount of unseen archive footage that builds on what we have seen from El Grupo’s 16mm material that ended up in Saludos Amigos and South Of The Border With Disney. Those films have been referenced here occasionally, but the complete story of their trip has been pulled together uniquely from extensive photographs, concept images the artists drew on location, and – most wonderfully of all – first hand accounts of the thoughts and feelings of those who were there via readings of personal letters to family members, reminiscences by those that were children at the time, and from archival “narration” from Walt himself.

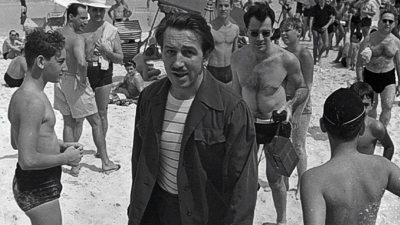

Of course, Walt & El Grupo is still a Disney production, this one produced by the Family Foundation, and so although honesty is the policy, those searching for anything on Walt that is less than flattering won’t find anything here, and that’s perhaps because there’s nothing to find! In fact, if nothing else, the location footage here – such as Walt vigorously joining in a Gaucho dance – clearly demonstrates that Walt Disney. Was. A. Dude. Seriously, the way he throws himself into engaging with other guests at events, even when short on sleep and worried with Studio politics back home, just goes to show again what an amazing human being the man was. The documentary is probably preaching to the converted, but on the evidence here there’s nothing to suggest any untoward word towards him hasn’t been touted by a jealous few.

There’s a sometimes frustrating swapping of pace or depth in director Ted Thomas’ film, however. Although I’m clued in on the 1940s Studio strike’s history, it’s perhaps not quite as fully explained as it could be for those coming to these facts for the first time, in anything but archival sound bites that do paint an adequate picture but somewhat skims over, or so I thought, some important context, even if Walt’s view on this time is heartfelt and was obviously a blow to him. Once the adventure begins, likewise, there are one or two instances where I thought too much time was spent, and again some moments that I would have liked to have known more about. Especially towards the end, the emphasis is on Saludos Amigos, without much mention of the other films and shorts that continued to draw on the Disney trip well into the late 1940s, although there are some nice comments from the South Americans on Amigos’ failures and successes, the highlight of which must be the wider recognition for Aquarela do Brasil that the film showcased.

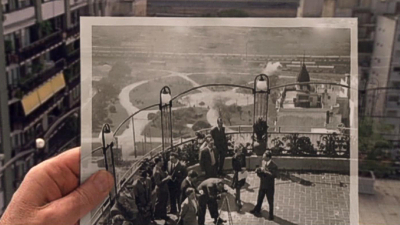

But as a way to place the viewer in a time capsule and send them back to the 1940s, the film does do a good job of making us feel as if we are there. The sheer quality of the film footage – all correctly screened in original ratio instead of being re-framed – is striking: a few light print mark instances apart, the color is astonishing, the clarity razor-sharp. Many of the photographic stills have been dimensionalized in that still-impressive modern documentary style, bringing depth to the images that, when combined with the locations and background scenery as it is today, is quite remarkable and no mean feat to pull off. And it’s absolutely fascinating to compare the Brazil, Argentina and Chile of the 1940s with the same areas almost 60 years on, the color and rhythm of the cities expressing their cultural identities through the exuberant music of the region.

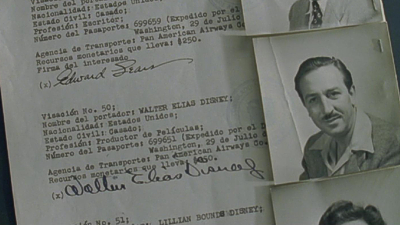

As such, any shortcomings I may have mentioned fall by the wayside when one considers the achievement of telling this story so many years later. There’s such a wealth of fascinating new angles on stories and details that many fans may already be aware of, that even they will be in awe of the way that information has been presented here (an early showing of the groups visa application forms being a distinctive way of naming who went, while putting faces to those names). There’s also a great selection of interviewees, Diane Disney-Miller (at times looking like the spit of her father), animation expert John Canemaker, film historian JB Kaufman among them…all of them offering their specialist take on events among the listless folks who offer their memories, or relay others’, at times often wryly amusing.

In fact, if anything, I might have appreciated more on what was happening around the group, in terms of the Nazi threat and their impact on the region, since any levels of danger el groupo may have been near isn’t really touched upon, and the documentary maintains a level of lightness that only occasionally dips into the politics of the time. Once again, however, this is not a true criticism, since the focus is clearly on Disney and his associates, many of which are profiled at points during the documentary. And this amounts to an excellently dedicated film that sticks closely to its core subject, and instead of providing everything the viewer may need, offers all the details one needs to then go off and discover more (perhaps via Kaufman’s accompanying book, South Of The Border With Disney).

This dispels the need to wander off into tangents that could have diluted the central message, and keeps Walt & El Grupo a very intimate affair, both in the personal nature of the letters that are read and in the stories of the people that were touched, either directly or by association, by Disney’s visit. Not that the film takes itself too seriously: dry humor is rife, such as the journalist who explains that the concurrently on tour Bing Crosby didn’t make many headlines during his visit (“We didn’t care about Crosby, and he didn’t care about us either; he only wanted to play golf!”), or the mini-montage that has fun with the urban legend that Walt was frozen after his passing (one of three Disney urban myths that Argentineans are said to believe, though the other two go unmentioned). I could go on and on at how much value I found in the film, but the best thing is that you buy a ticket and join Walt & El Grupo and experience the trip yourselves: you’re sure to be in for a wonderful ride!

The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story (2009, 102 mins)

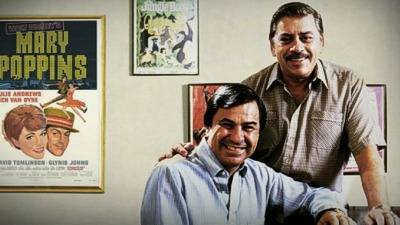

We leap twenty years into the future for this next entry in these releases, to when the Disney Studio was over the effects of the War and things were thriving creatively and commercially. Television and the Disneyland theme park had injected a huge amount of fresh energy and creativity into Walt Disney Productions, and Walt’s attention to live-action projects had grown to where he was producing regular family fare in that area as well. Still pivotal to those successes would be the kind of songs that had been a Disney trademark since Who’s Afraid Of The Big Bad Wolf? had proven a hit in 1933, and by 1964, songwriters Richard and Robert Sherman were the go-to, in-house “boys” that were about to hit their zenith with the score for Mary Poppins, which would go on to win them Academy Award recognition.

The Shermans had come to Disney’s after the writing of a couple of successful bubblegum pop hits had them invited to pen a song for then-Studio popstrel Annette Funicello (think Disney’s Hannah Montana of the 1950s). Tall Paul was another hit, and in Walt’s inimitable way, he soon had the pair on staff, writing songs to measure for a variety of television, theme park, live-action and animated projects. They loved working for Walt, and he loved them, which would cause some consternation among some other Studio employees after Walt’s passing. All through this period, they were the jovial, always fun to be around Boys that could come up with the witty lyric or hummable tune that stuck in your head for days on end (It’s A Small World, anyone!?).

Though produced two years before he died, Mary Poppins would prove to be Walt and the Shermans’ crowning collaboration, but as the composers took to the stage to accept their awards on Oscar night, little did the world know that the happy, brotherly image that they had portrayed – and would continue to shape – over the years was a fabricated smokescreen to conceal the fact that they had very little in common, didn’t socialize outside of work hours, and at times couldn’t stand the sight of each other so much that the two sides of their families hadn’t interacted with each other until the production of this documentary…

That’s the surprising truth very much revealed in this fascinating behind the tunes film directed by the Shermans’ sons/nephews Jeff and Greg, who cleverly skip any potential “who goes first” arguments by switching around their names for producing and directing credits. Before travelling back in time to witness their story, we meet the Brothers as they are now: Dick still in Los Angeles, where he maintains interest in his work through participating in documentaries and bonus features for home video release (he was a major, and very cheery, component of Mary Poppins’s 40th Anniversary DVD), and Bob, now living in London and preferring to stay out of the limelight to concentrate on his personal paintings.

Their story begins with their father, Al Sherman, a piano performer who provided mood music for silent movies before becoming a successful Tin Pan Alley songwriter during the Great Depression. At young ages, Bob and Dick weren’t interested in their father’s music: Dick joined the Army, and Bob wanted to be a poet, but a fortuitous circumstance saw their father betting they couldn’t work together to come up with a good song, as a way to end their constant sibling rivalry. It was this clash of egos that was to fuel their relationship into the future, coming together to pen some of the most influential and memorable melodies and lyrics of the last century with intensity, only to drift apart at the end of the day. Studio publicity certainly played a part in representing the pair as happy go lucky brothers, but that depiction couldn’t have been further than the truth.

The Boys, therefore, as much as it is a salute to the Sherman Brothers careers and legacy, is the definitive word on their lives, even more so than their wonderful autobiographical book Walt’s Time, which had previously come clean about a handful of aspects of their time together but fell well short of dropping the bombshell about how they felt about each other. In many ways, The Boys plays as a companion to Walt’s Time: being a profile of the duo, some information is sure to be repeated between the two, but then each outlet contains so much more.

In fact, as with Walt & El Grupo, there were times in The Boys when I wanted to know more about a certain project, and for the film to slow down and focus on areas other than just their work for the Disney Studios. It does do that, providing a complete portrait of Dick and Bob from young boys up until the Broadway premiere of Mary Poppins just a couple of years ago, but it is perhaps inevitably very Disney focused after an initial period which takes in a visit to the Boys’ childhood home and background information on their father Al, one of whose early hits was for Maurice Chevalier, which is mentioned, though the Brothers’ later writing for the performer in In Search Of The Castaways and The AristoCats, which I’ve always thought was a lovely full circle association, is sadly overlooked.

Where The Boys really shines, whatever the animosity between the brothers, is in the smaller stories and anecdotes. Bob and Dick have recorded their reminiscences separately, and sometimes the same story will be remembered by both, sometimes they’ll have different memories, each variation leading to either an amusing tale or an amusing disagreement of the facts. And of course there’s the music, with a catalog of verses, choruses, movie clips and performances peppering the entire film along with remarks from colleagues, friends and admirers including Randy Newman, Ben Stiller (also an executive producer on this film), Barbara Broccoli, John Landis, Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, Hayley Mills, Angela Lansbury, Milt Larson, Roy Disney, AJ Carothers, Marty Sklar, John Lasseter, Robert Osborne, Leonard Maltin, Brian Sibley, Sam Goldwyn Jr, Bruce Gordon, Alan Menken, John Williams and Jeff Kurtti, another producer of this film, editor of the Walt’s Time book and previously the creator of Disney’s best home video supplemental features from the 1990s.

The first half of the film is more excellent documentary filmmaking, emotionally presenting the pair’s upbringing and introduction into music, and early endevors to make a name for themselves, including the penning of You’re Sixteen, much later a hit for Ringo Starr. Once they get to Disney’s the film hits a new stride, but it skips a fair chunk of achievement out to get quickly to Mary Poppins, which rightfully hogs a lot of the screentime but unfortunately at the expense of not mentioning other milestones, such as The Sword In The Stone. However, The Boys does a remarkable job of covering this period without repeating a lot of what we already know, even with its plentiful use of archive material, which has a magic of its own, and looking at their wonderful use of inventive wordplay.

After the lengthy focus on Poppins, a diversion to appraise It’s A Small World, a quick trip to the Hundred Acre Wood and a dip into The Jungle Book, when it comes to having to say goodbye to Walt, both Dick and Bob’s genuine emotions come to the fore, and I must admit to welling up myself, and not for the only time during The Boys. What a shame the Studio’s view of them changed without Uncle Walt around, and whatever streak of jealousy might have been floating around at them being Walt’s favored sounding board certainly made itself clear, as the phone stopped ringing and the assignments dried up. It’s here, although Chitty Chitty Bang Bang gets a fair share of screen time, that The Boys then becomes a little bit of a run-through of other projects, name checking them instead of shedding any new information on them, such as the fact (as nicely mentioned in Walt’s Time) that Walt had given them his blessing to go write the songs for Chitty before his passing.

It’s perhaps true that, Chitty apart, not all the Shermans’ post-Disney musicals made the same kind of impact on audiences that their earlier work had done, but this was a prolific period and some of their output from this time is potentially much more interesting to learn new things about. I’d have greatly cared to hear more on their return to the Studio for The AristoCats and Bedknobs And Broomsticks, and how those projects came about after they had originally left, as well as more than the cursorily glimpses given to the original Charlotte’s Web, Snoopy Come Home, The Slipper And The Rose, Little Nemo, their second return to Disney for The Tigger Movie and the recent stage incarnations of Chitty and Poppins.

Both of those stage productions, more than anything, showcase how contemporary and popular the Shermans’ work still is, but there’s rather little on them, especially Poppins, and the reason as to why two British composers were hired to add new songs instead of the Boys. It was, sadly, a stipulation of PL Travers’ original contract with Walt, but it isn’t mentioned or even alluded to, making it look as if they’re responsible for the entire stage score, which is a little cheeky, to use Mary’s word. But then there are other moments that easily convince one to forgive any faults: Wings guitarist Laurence Juber riffing on A Spoonful Of Sugar and Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour’s super-smooth rendition of Hushabye Mountain are gems in themselves, as is the admission from Bob that his favorite Sherman Brothers song is Summer Magic’s On The Front Porch, a song I often find myself humming unconsciously.

As the film closes, The Boys reverts to the highly personal thoughts and feelings that obviously mean a lot to, and have impacted upon, Bob and Dick. And although some of their work is passed over too quickly, this is really how it should be, since there is only a certain amount that can be featured in a film such as this, and the focus is rightly on their personal relationships. A last bit of fun is featured in a Disneyland-type song they wrote for Landis’ otherwise redundant Beverly Hills Cop III and a couple of cameo scenes they had roles in: Bob with fellow Hollywood veterans Ray Harryhausen and Arthur Hiller and Dick…well, unfortunately his place as the MC of a marching band hit the cutting room floor, leaving the more reserved Bob to have the final word, in this instance, over his brother, who is remains ever the showman.

Quite rightly compared to Gilbert and Sullivan, Rodgers and Hammerstein and Lennon and McCartney (by Micky Dolenz in the supplemental features) in both their demeanors and the lasting legacies in the world of music, this film finally provides a suitable way to remember and make a big deal out of crediting Richard and Robert Sherman with an appropriate celebration of the achievements they accomplished. In the antagonism they shared, real magic was forged, and it’s the kind of enchantment that will live on longer than any of us, in the many songs they wrote and the projects they touched, including this painfully honest but genuinely moving and wonderfully warm tribute, to The Boys.

Waking Sleeping Beauty (2009, 86 mins)

Two decades after the Shermans had enjoyed the height of their Disney success, we jump forward again, to 1984, though by this time the Studio, especially the animation department, was not in the best of health. Walt’s passing had left the Studio without its chief, and his duties were picked up by a management board that constantly asked the question: “What would Walt have done?”, something of a conundrum to answer, since one could pretty much bet Walt would have done the complete opposite to what anyone would have thought he would have done!

After a short run of films that Walt had approved before he died (The Happiest Millionaire, The Love Bug, The Jungle Book, The AristoCats, Bedknobs And Broomsticks), the Disney films of the 1970s are often derided, sometimes by the Studio’s filmmakers themselves, for being run of the mill, safe and unremarkable outings. I think this is unfair on the whole, and there’s a good selection among the admitted dross that still stand up as breezy, inoffensive entertainment that, if nothing else, at least kept the Studio afloat during this period of change that affected not just Disney’s but all of Hollywood as well.

The Studio’s reaction was to perhaps go too far in the opposite direction, leaning towards quasi-adult thriller, suspense and “horror” (such as it was, as in The Watcher In The Woods: tagline, “This is not a fairytale”). Expensive, showy flops included The Black Hole and Tron, and animation had gone from the charm of The Many Adventures Of Winnie The Pooh and the record setting The Rescuers to the darker realism of The Fox And The Hound and the supernatural fantasy The Black Cauldron, a watershed moment in the Studio’s history when great change was needed – and fast!

This change came, of course, with the introduction of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg to the Disney board, having been brought in by Roy Disney after a potential buyout of the company would have left it asset stripped and as good as finished. This is where director Don Hahn’s feature documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty picks up the story, the film being an attempt to tell the story of the “Disney renaissance” between 1984 and 1994…or “The Katzenberg Years”, as it could also be called regarding his arrival and departure at the Studio. In fact, although Waking Sleeping Beauty is ostensibly the story of an animation studio rising from despair, it’s primarily the story of three men, Katzenberg among them, whose egos fought to be the public face of this re-emerging powerhouse.

Hahn uses The Lion King as a framing device for his film, perceptively using one of Disney’s biggest hits as an audience-friendly way in to the struggles and fortunes (and more struggles) that we are about to witness. Here, we’re on the eve of the film’s soon to be enormous critical and commercial success…a success that brought with it much behind the scenes jostling for attention that belied the magic kingdom image that Walt Disney Feature Animation, as it was then, projected in its films. It’s a story that many followers of the Studio will already know, but you’ve never seen it illustrated and presented like this: not only was Hahn there, but he was someone high up in the Disney Animation echelon and so privy to perhaps more than the just the regular day to day rumblings that many of the artists spoke about between themselves.

Artist discontent had almost started from when Walt passed on and a new generation of artists were trained by the fabled Nine Old Men, who passed on their animation know-how. But the Studio’s budgets in the 1970s meant costs were tight on films that didn’t really allow the artists to express themselves: here they were finally working at Disney’s – for many of them their dream jobs – but they were churning out “more of the same” as opposed to creating new Snow Whites, Pinocchios or Fantasias. In the late 1970s another Don, Bluth, had led a studio artist walk-out, leaving the unit at an all-time low. One of Waking Sleeping Beauty’s early masterstrokes is in being able to present animator Randy Cartwright’s illicitly filmed (by cameraman John Lasseter) home movie tour of the Animation building, where the discontent is not only clear, but more of a surprise than I had ever imagined.

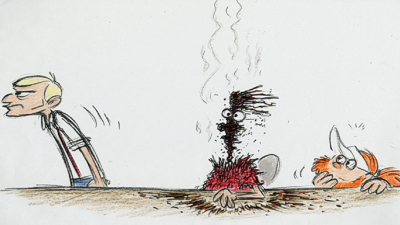

The acerbic wit is biting: a flip of drawings from a Peter Pan scene produces the comments that “It’s better than the magic we’re making today, but we can’t help that”, while another comment, actually in the disc’s bonus features in reply to what an animator is working on, is “the same cartoon we were making ten years ago”. It’s fantastic to be able to see these hither-to unseen snippets of genuine working life at the Studio, as well as the youthful faces (including Joe Ranft and a authentically out of place Tim Burton…no wonder they didn’t know what to do with him!), all of them happy to have made it where they were, but clearly pining to push themselves much more than was being asked of them. An agonizing moment that depicts the alternate attitudes to the old guard and the new talent is when Phil Nibbelink is demonstrating how The Black Cauldron’s Creeper could move, dancing boisterously and trying to elicit a reaction from an uncomfortable Ted Berman).

The bombshell came when a greenmailing scam cooked up by corporate raider Saul Steinberg led to a complete change of management in 1984, in a last ditch attempt by Roy Disney to retain the company. Walt’s son in law, Ron Miller (husband to Diane), resigned, and in came Eisner and Wells, soon to be joined by Katzenberg, who was given the “problem” of the animation department to solve. As well as ample amounts of archive material from a hugely impressive variety of sources, Hahn is almost unbelievably able to draw on new conversations with those at the heart of the storm: Eisner, Katzenberg and Roy Disney, in the last major interview before his passing late in 2009. But distinctively, Waking Sleeping Beauty doesn’t resort to on-camera talking heads: the words of those participating among many others) accompany Hahn’s narration and the archive footage, at times cleverly suggesting two alternate facets of the same moment in what we are seeing and the underlying truth.

Identifying the speakers (which also include the film’s co-producer Peter Schneider and a swarm of artistic and directorial talent) are cartoon speech bubbles that pop up throughout, another neat little touch that simply keeps the momentum of the film rolling towards its tight and trim running length. This means that the film both has time to squeeze in fun little moments like Eisner plunging a cream pie into Wells’ face back when they had first arrived and everybody got along, but also skims over other instances: much exposure is given to Beauty And The Beast’s Oscar hopes (and Golden Globe win), but it seems a shade unfair not to mention the awards it did win for Alan Menken and Howard Ashman in the song and score departments. Those were perhaps not as significant as a Best Picture, but started a streak for Disney Animation that saw Menken and Tim Rice win for Aladdin, and Rice and Elton John for The Lion King and was set to continue beyond the scope of this film.

But there’s so much other good stuff that maybe those omissions don’t matter, even if Waking Sleeping Beauty is perhaps the least revelatory of these three documentary films because the events depicted, at least for the majority of those reading this review I would imagine, happened recently within our lifetimes. It’s no less interesting for that, and in fact it may be more interesting to younger viewers than Walt & El Grupo and The Boys as it portrays Studio life during the production of the 1990s films they would have grown up on more candidly than the glossy “making ofs” that were previously the company line.

Waking Sleeping Beauty is also more than just a confirmation of the stories and rumors we may have heard, such as the infamous Basil Of Baker Street memo that had a wry artist rename the previous Disney animated features to given them inane titles due to the marketing department’s insistence that The Great Mouse Detective was a better fit (a situation, with Tangled’s recent name switch, that the Studio has done well to smooth out before history repeated itself). There’s also Katzenberg at one point suggesting that Part Of Your World is removed from The Little Mermaid, an LB Mayer moment akin to when Over The Rainbow was nearly chopped from The Wizard Of Oz. In both cases, of course, those songs went on to really make those films, Part Of Your World still being the definitive Disney “I want” song.

If anything, Katzenberg plays the most omnipresent role in the story: he’s not only attributed a remark that gives the film its title, but a caricature sketch of him provides the basis for the poster. The relationship between him and the artists is complex to say the least; he arrives at the Studio with a brusque manner and begins to cut Cauldron’s finished animation scenes to tighten the movie, and quickly moves the unit out of the Animation building to a warehouse in Glendale, which leads to thoughts of “the horror, the horror” of a Disney Animation apocalypse. A fix of sorts comes with the introduction of Schneider, who revolutionizes the thinking process and gets everybody excited about animation again, leading to the successes of the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

After the rough introductions, respect clearly forms between the two factions, and it’s interesting to see the relationships forming, as well as the cracks appearing and how that old Disney magic was sprinkled over them: in a press interview, John Musker, asked how Mermaid was picked for production, says that “This is sort of more the truth than what we may wind up saying later”. The impact of Howard Ashman’s music and story sense is greatly explored as a major component of the triumphs of the first renaissance pictures, the increasing success of which finally unleashed the growing personalities that, with the sudden and shocking accidental death of Frank Wells, set up frictions between Katzenberg and Roy Disney, and Eisner and Katzenberg. Some inappropriate behavior at Wells’ memorial is unbelievably misjudged (and is that Roy almost flinching as Eisner returns to grab the microphone?).

But although Waking Sleeping Beauty takes a warts and all approach, those expecting a terrifically controversial exposé may be disappointed (not that I was, at all), since this is above all a celebration of the ten year period when Disney Animation came back from the brink, whatever long hours might have disgruntled the artists and however many egos were bruised along the way. However, the honesty is sometimes breathtaking and the stories often outrageous, all of them relayed to us directly through the sights and sounds of the times. More than anything, I was surprised at how overlooked Katzenberg seems to have been by his colleagues: at first only interested in making as much money from animation as he could, he became a huge proponent of the art form in the company and did not get the recognition for the turnaround he has instigated.

This, naturally, led to him being resigned from The Walt Disney Company after what seems to be a genuinely heartfelt thank-you message to the animation crews, a moment that comes in the closing stages of this profile and a subject that, unfortunately, the film does not address, leading to the creation of a real competitor for Katzenberg’s old employers with the emergence of DreamWorks. The closest the animosity between Disney and that new company gets to being mentioned is in the end credits, where in a DVD bonus feature outtake, Eric Goldberg asks “Am I allowed to mention Jeffrey Katzenberg?” in regards to the Studio shutout of his name throughout the post-Lion King 1990s and early 2000s.

It’s this next period in Disney Animation when the infighting really begins, when with the loss of both Wells and Katzenberg, Eisner lost his touch and started to second guess himself, leading to the infamous micro-managing that eventually turned Roy Disney to create the Save Disney campaign against Eisner. The heart of this period has already been documented in a film apparently so brutally candid that it remains unreleased by the Studio: Trudie Styler’s The Sweatbox, following her husband Sting’s involvement with what was Kingdom In The Sun and eventually became The Emperor’s New Groove after much upheaval captured on film.

Further to that, the independent film Dream On Silly Dreamer documented the following events, as Disney Animation took a continuing spiral downward, closing down satellite animation studios in Florida and Paris, and began the switch to Pixar’s brand of computer animation instead of preserving its own hand-drawn legacy before Eisner eventually left, and Robert Iger brought in the Pixar team to rejuvenate the animation department. With The Sweatbox practically suppressed and the focus of Waking Sleeping Beauty on the earlier, prouder period, the film perhaps works best at placing the entire chronology of events into context for what was to come. But it’s also a reminder of how, right back at the beginning, how well everyone got along and did their jobs well, creating timeless and artistically valid entertainment that will stand the tests of time just as much as the films of Walt Disney and his crews that inspired them.

If you haven’t guessed already, I’m wholeheartedly recommending all three of these Disney documentaries as essential additions to any serious animation collection, Disney-orientated or not. Although many may well know the stories behind these three periods in the Studio’s history, there’s still much to learn, open your eyes to, and actually enjoy in a way. It would be impossible to place them in any kind of order, as each present totally different subject matter in unique ways; Walt & El Grupo as an archival adventure that authentically manages to turn back time, The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story as a definitive character portrait of two insanely creative men, and Waking Sleeping Beauty the more familiar in terms of the personalities and events, but then perhaps additionally as fascinating as a result.

In any event, far from being “bonus extras” as some might suggest, all three of these documentary films are more than proficient features that have been crafted to stand alone and also work as a group, providing a triple helping of Disney treasure in their own right that I sincerely hope continues with the release of more of the same in the years to come.

Is This Thing Loaded?

In keeping with these kinds of truly core-collectors titles, all three of these releases forgo the usual promotions for upcoming Disney product, save for trailers for each of the other two documentaries on any one disc. There are also generic Disney Blu-ray and 101 Dalmatians anti-smoking spots (as a quasi-disclaimer for some of the onscreen consumptions of tobacco products seen on the discs) and optional previews for Fantasia, Bambi, Lion King and the D23 fan community, but nothing in the way of useless Buddies commercials or Disney Channel fluff…it’s all good, collector’s stuff here, and nice to have the trailers for all three films spread among the three discs.

Each menu has been tailor made for each title, but they share a common ground in all being a panning montage images, maps, timelines and film content that provide the right mood for the documentary chosen to view. The extras packages for each film are, like Frank And Ollie and Walt: The Man Behind The Myth before them, as interesting as the films themselves, providing added nuggets of information and interest that do a good job of spending more time on sections from the films themselves that may have felt they needed more attention. This has the effect of going a long way to making the documentaries and these supplements feel part of a whole package, like three singular experiences waiting to be explored.

Walt & El Grupo’s extras begin with a full-length Audio Commentary track from director Ted Thomas and JB Kaufman, author of a companion book to the film. While you may wonder what the benefit is of a commentary track on a genre of film where talking heads and interviews are already prevalent, it’s easy to forget that Walt & El Grupo is an entertainment just as mush as the resulting South American films, so there’s still much to learn that couldn’t be incorporated into the film itself. Not only that, but the participants relay their intentions for their film and their approach to the archive material…extremely interesting remarks that add context, further historical significance and notes on those who appear onscreen.

One of the film’s most unique aspects is the telling of the story through still photographs, which have been used in various ways to bring life to them, and Photos In Motion (2:44) looks at how these techniques were applied, as well as a “photo album” approach that was discarded. From The Director’s Cut offers up three additional scenes that add to the appreciation of the feature. In Home Movies For The Big Screen (2:08), JB Kaufman explains how El Grupo’s 16mm footage wound up being used in the eventual South American pictures – including a very “sneaky” secret that I won’t spoil here! My Father’s Generation (2:17) and Artists And Politicians (3:50) both provide a little more context on Walt’s travelling group and the era itself.

All this material and the extras found in the LaserDisc Archive Collection edition of Saludos Amigos/The Three Caballeros would make for an excellent Disney Treasures tin, but next we have the next best thing on DVD, and while it may feel strange to have a classic feature appear as an extra to a documentary on its genesis, it’s a very welcome and worthwhile addition. Released on home video previously uncut, recent disc editions of Walt’s first South American film have digitally removed a cigarette from Goofy’s hands in one sequence, so as to not encourage children to follow the example of a popular cartoon character, but leading to complaints from purists. Well, fear not, for here is the complete, uncut, original edition of Saludos Amigos, presented in full at 42 minutes (nope that’s not a typo: the film is well known for being Disney’s shortest feature, even beating Dumbo’s 64 minute running time).

A short disclaimer card doesn’t go as far as suggesting we shouldn’t smoke, but offers an explanation as to why the feature has been included on the disc. Looking about as good as the recent double-bill release with its stable mate The Three Cabelleros, the film isn’t in the HD restoration league, but looks very stable, roughly on par with the Disney Treasures animated shorts collections (though unfortunately not chapter indexed). After viewing the documentary, it makes perfect sense to see one of the results of the trip, and such close proximity between the two reveals one or two aspects that I’d not noticed or been wise enough to pick up. As a companion to the film, original theatrical trailers for Saludos Amigos and its sequel The Three Caballeros are both included (3:50 combined), looking as if they have been directly ported over from that CAV LaserDisc set, but huge fun for being of the period.

There’s just as much to be found in The Boys supplements, including a clip explaining Why They’re “The Boys” (2:36), the nickname they were given as youngsters that stuck through their association with the Disney Studio and to this day. Offering a little more context on their time at Walt’s, Disney Studios In the ’60s (3:32) reflects on their ten years at the mouse house, while Casting Mary Poppins (3:39) recounts the famous story about how Julie Andrews was passed over for the film version of My Fair Lady, the role she had originated on stage, and landed Poppins instead, eventually beating out Audrey Hepburn to win Best Actress (and her smash follow-up The Sound Of Music)!

The Process (4:20) deconstructs the Shermans’ approach to their “looks easy” songwriting style, with comments from various others involved in their field including Alan Menken, and Theme Parks (9:08) expands on the creative process for this alternative medium, looking at some of the various songs composed for such attractions as The Enchanted Tiki Room, Carousel Of Progress, Magic Journeys and, of course, It’s A Small World.

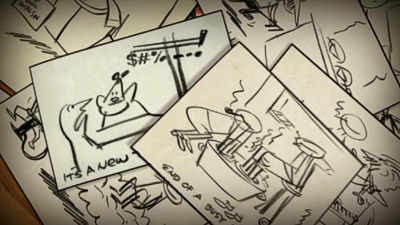

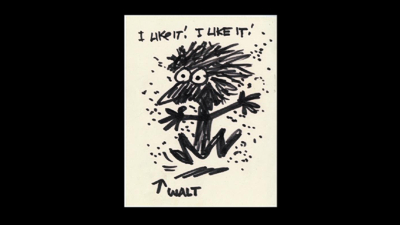

Artwork of two different kinds are showcased by storyman Roy Williams (3:23), who used to slip quick comical sketches under the Boys’ door, and via Bob’s Art (2:15), which presents a handful of Bob’s own paintings. As if the movie wasn’t enough, a supplemental Celebration (3:52) gathers a whole host of fans and musicians to pay tribute to the Boys, as a nice way of wrapping things up with final thoughts from their fans and contemporaries.

But we’re not done yet – a Sherman Brothers’ Jukebox isn’t quite as simple as it sounds, and instead of just offering up clips from various programs, shows and movies, this is an even better selection of further explorations at how some of these songs came to be, ranging from one of Al Sherman’s 1924 hits performed by Eddie Cantor as a sound test and the Boys’ debut for Annette, to the origins of Chim Chim Cher-ee, the performance of There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow with Walt, and an animated Wienerschnitzel commercial. All together, these clips, running between thirty seconds and a few minutes, play for around 20 minutes, a highlight surely being the chance to hear Laurence Juber’s full version of his exuberant A Spoonful Of Sugar, in which he evokes the entire orchestration of the song on his guitar…pure magic!

The uncut Saludos Amigos apart and saving the most bountiful amount of supplements for last (but by no means least!), Waking Sleeping Beauty’s extras provide perhaps the most excellent selection of companion segments to its main feature. Why Wake Sleeping Beauty? (8:53) is essentially a “making of” featurette that expresses Hahn and Schneider’s intent for the film to be a celebration of the period it covers and some of the angst they shared during its production in making sure that message came across while being true to events, a feat they absolutely succeed in pulling off in the final film.

The Sailor, The Mountain Climber, The Artist And The Poet (15:25) looks at the film’s quadruple dedication, to Roy Disney, Frank Wells, Joe Ranft and Howard Ashman, going on to briefly profile these four individuals who played significant roles in the story of Disney Animation at this time, and note how Disney’s name was rightfully added to the film following his death soon after its premiere. A Reunion (2:12) brings together directors Kirk Wise and Rob Minkoff for a brief but fun reminisce about how long they have known each other (amusingly remembering a theme song from an amateur short film they made in their childhoods), and Walt (6:00) pays tribute to the founder of the company and pioneer of the medium that are both a central part of this film, and the similarities between Walt’s time and the events depicted here, although it is amusing to hear Cartwright blast Disney’s non-strictly true documentary style when we’ve just seen the truth behind the whitewashed 1990s at the Studio and how some Lion King story meetings were staged for the cameras, just as Walt had done back in the day.

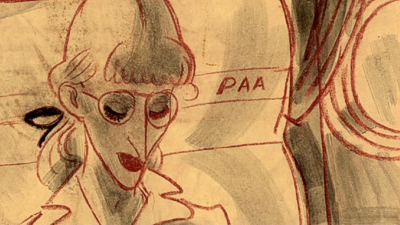

More mini-documentaries than actual moments removed from the main feature, a selection of Deleted Scenes cover other aspects of Studio life during the 1990s, in particular the effect of Howard Ashman on the artists. Black Friday (4:40) recounts the day Aladdin was restarted from scratch and a song very close to Ashman was removed, and Howard’s Lecture (12:33) presents a lengthy stretch of Ashman’s inspirational 1987 talk to the animators about his musical background and interest in working with the Disney animation medium, while Losing Howard (4:53) expands on the terrible loss to the department when he admitted he was dying from HIV.

This is all made the more apparent by seeing Howard in action with Jodi Benson while Recording Part Of Your World (6:30), with the lyricist providing crucial notes and guidance to Benson that shapes her vocal intonation from this version to the final, gut-wrenching performance as used in the film. Research Trips (4:19) looks at the inspiration-gathering tours of Australia, France and Africa that provided stimulation for The Rescuers Down Under, Beauty And The Beast and The Lion King, and finally To Sir With Love (1:39) suitably demonstrates simply how much affection the animation crews had for Jeffrey Katzenberg by the end of 1994, a “huge shift” being felt at the Studio after his departure.

Even better are The Disney Studio Tours (14:30), Randy Cartwright’s home movies shot incognito wherever the animation department was housed at three various points in time. 1980 in the animation building wasn’t exactly the happiest place on Earth, and Cartwright and cameraman John Lasseter’s visits to their colleagues are peppered with sly remarks about the then state of the art. Much of this has already been seen in the feature itself, so this is an alternate cut of sorts, not actually presented totally in full, unfortunately, but giving us a flavor of some moments in full and of others as yet unseen. Highlights include the hilarious “easy as pie” way to make an animated movie and more catching some of the old guard off guard and looking uneasy at the impromptu camera shoot.

Cartwright’s 1983 goodbyes as he leaves for Japan to animate on Little Nemo: Adventures In Slumberland (incidentally with songs by the Sherman Brothers) also serves its fair share of hindsight-amusing moments, such as when someone proclaims The Black Cauldron will be “the best that Disney picture ever made” and Lasseter says that he’s working on setting up The Brave Little Toaster elsewhere while “putzing around” with some computer graphics work, and there’s a hilarious farewell from a Peter Lorre-voiced Joe Ranft. 1990’s tour sees great changes: now shot on videotape, the animation department was working off the original Disney lot, but Cartwright drolly retains the same shirt he wore to host the previous films, humorously predicting flatscreen TVs of the future, wondering where Tim Burton and Lasseter are (he’s said to be away doing “computer stuff”) and just about sneaking by an observant security guard!

Finally, topping even those home movies, a feature-length Audio Commentary plays as a kind of alternate soundtrack, not only featuring director Hahn and co-producer Schneider’s filmmaking remarks and additional insights into the archive footage shown in the documentary, but further audio interviews old and new that add different perspectives on the events as they are shown to unfold. Waking Sleeping Beauty is already filled with more exploration into the creative process than most films receive on DVD, but this track offers so much more, including from the hip thoughts from many names that will be familiar to fans, such as Glen Keane’s opinion on rival An American Tail’s success and welcome comments from Andreas Deja, who is conspicuously missing from the finished film. All in all, another fantastic collection of supplements that compliment the film perfectly.

Case Study:

Okay, so we’ve no Treasures tins this year, but in all other respects the packaging is much more in keeping with those collectors’ editions than your average Disney home video release. For starters, each title (in initial print runs at least) come housed in a nice slipcover that preserves the art for their original theatrical posters, with accurate descriptions of the bonus features to be found inside on the back of the sleeve. Interestingly, the Disney name isn’t as overly promoted as usual, and indeed these releases carry the Buena Vista logo, perhaps as an added indication that these are not “regular” mouse house releases.

Adding to the Treasures feel is that each disc comes with a “special collectible”: a Disney Studios/World War II Timeline fold-out stretching from 1937 to 1942 in Walt & El Grupo, a Feed The Birds Music Sheet repro from 1963 (when it was known as Tuppence A Bag) for The Boys, and an amusing Lithograph Print that reproduces a caricatured moment by Kirk Wise from a meeting with Howard Ashman when a suggestion was not exactly well received! There are no other inserts, other than Movie Reward codes and Blu-ray promos, and disc art is a uniform silkscreen grey across all three titles, but these are classy and better than expected.

Ink And Paint:

With each film a mix of brand new interviews and framing devices combined with plentiful amounts of archive material, the overall quality on all three films is far more consistent that you might expect. This is due, especially in Walt & El Grupo, to the 16mm location footage looking unexpectedly vibrant and solid, while The Boys benefits from pristine movie clips. Pleasingly, all the archive segments across these first two films have been preserved in their original aspect ratios, and even Waking Sleeping Beauty’s multiple sources and formats have been processed for the best available representations.

With a fair amount of subtitled speakers in Walt & El Grupo, I wasn’t too impressed with the thick, yellow font, which is player-generated as opposed to the delicate and thin white text that featured in the original prints. This is necessitated by the need for being able to switch between subtitle languages in English and Spanish, as well as a subtitle option for Thomas and Kaufman’s commentary, but perhaps a nicer, more appropriate and not so obtrusive font could have been selected or the color muted…or even the placement shifted down so that it wasn’t so far up in the screen area! It does what it needs to do, but brings an unneeded attention to itself, which could distract when it should assist.

Scratch Tracks:

With much of each of the soundtracks made up of recordings made under controlled conditions, either from interviews or musical underscore, there’s really nothing to complain about with any of these discs’ mixes. Archive footage in Walt & El Grupo is mostly silent, so new effects have been added for ambience, while The Boys and Waking Sleeping Beauty draw from multiple sources that have been greatly sweetened and so don’t exhibit any audio distractions or level discrepancies. English and Spanish dubs and subs are optional on the first two films, with each Audio Commentary track also subtitled in English.

Final Cut:

I think there’s a tremendous three-disc “South Of The Border With Walt Disney” boxed set that could have been put together combining Walt & El Grupo, the two South American features, Walt’s own original documentary featurette on the trip and the sheer wealth of bonus features found in the LaserDisc release of those films, and maybe that could happen if and when they make it to Blu-ray, but in the meantime, this is an excellent way to join Walt and his crew on location.

Likewise The Boys could easily be the centerpoint of a retrospective Sherman Brothers collection when the likes of Mary Poppins, Bedknobs And Broomsticks, as well as countless others, make their way to the hi-def format release, but it sings volumes that the film stands perfectly well in its own right, too, covering the kind of ground we might expect but also offering so, so much more amongst the personal stories and revelatory new truths behind the title duo’s relationship.

Waking Sleeping Beauty, because it covers recent events that many may remember, is perhaps less revealing than the other films, but conversely even more compelling as a result since it offers a completely alternate take on the fairytale image that was being portrayed publicly. Absolutely indispensable, it’s perhaps their “lightweight” (read: non-political or environmental) subject matter that didn’t see these films competing for major awards consideration, but they’re just as commendable and certainly worthy of being on your shelves. More please!

| ||

|