Les Armateurs/Vivi Film/Cartoon Saloon/France 2 Cinema (February 8 2009), New Video (October 5 2010), single BD plus DVD, 79 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition widescreen and 1.78:1 anamorphic, DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 and 5.1, Not Rated, Retail: $39.95

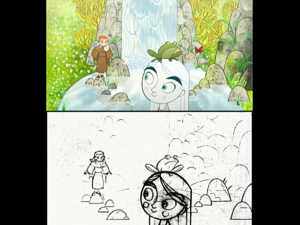

Storyboard:

The secrets behind the creation of Ireland’s lavish illustrated manuscript The Book Of Kells are revealed in this exquisitely animated feature. With the threat of a Viking invasion on their Irish monastery, an Abbot is too busy overseeing the building of a great wall to make a meaningful connection with his young nephew Brendan, who finds more solace with Brother Aidan, creator of a beautifully illuminated manuscript. But in order to help Aidan complete the book, Brendan heads off into the forest outside of the wall, where fantastic sights – and dangers – await…

The Sweatbox Review:

This year’s crop of Oscar hopefuls for the Best Animated Feature award was an eclectic bunch that represented well the three major techniques of animation, the traditional hand-drawn “classical” style, frame-by-frame model moving stop-motion, and the now approximately thirty year old use of computer generated imagery, CGI. Although inevitable winner was Pixar’s CGI feature Up, and there was a token acknowledgement that Disney had returned to its traditional roots with The Princess And The Frog, there was another hand-drawn film in the mix – something of a surprise in itself – and one that wasn’t having any difficulty in drawing its own very positive notices.

The only problem with The Secret Of Kells was that, with a somewhat limited release schedule, audiences couldn’t immediately rush out and see what the fuss was about without travelling for miles into the nearest town showing the film. That issue is naturally cleared up with the release of one of the film on Blu-ray and DVD, although I have to admit that, while viewing the movie, it wasn’t immediately clear as to what so many had appreciated in this otherwise unassuming production. The first thing that must be said is that I think you need a pretty good grounding in The Book Of Kells itself before watching the film. I know of this historically mysterious manuscript through vaguely remembered school lessons, but not anywhere near enough to prepare me for this “what if?” version of events leading to its creation.

Despite its critical success, I don’t think I’m going to be the only one who ultimately can’t quite tune into its story: from the opening frames, the design of The Secret Of Kells, taking its lead from the book itself, is so overwhelming and throws so much visual and plot expository information at the viewer, that I didn’t immediately engage with the characters or what the story set-up was trying to suggest, splintered as I felt everything was for the first ten to fifteen minutes. At which point things start to become a little more settled and simplified, and with some of the story streamlined down, we can start to identify more with the child Brendan and the wise old Brother Aidan.

Although many didn’t like the simplicities of Baz Lurhmann’s Moulin Rouge!, that was actually the film’s defining strength. With all the visual fireworks going on in almost every frame, the structure wouldn’t have supported a labyrinthine plot, something that would have suffocated it (leading to many criticising its style over substance…but what style!). There’s a lot of that here in Kells, where the continually mixing of styles, mostly in the backgrounds, can overwhelm the pages of dialogue that has characters saying one thing, doing another, and then changing their minds.

Perhaps it’s a case of trying to please all the investors (a staggering amount of around thirty companies are listed as participants in its production), but I would guess not, since such an event would lead any director to go schizophrenic, and Kells genuinely can’t be called that. But the inspirations are both clear and numerous, with parts reminding me of John Hubley’s aboriginal opening of Watership Down, much of Richard Williams’ work, such as the MC Escher-like and flat perspective backgrounds of The Thief And The Cobbler, and some dream/premonition sequences that recall The Little Island.

There’s also a bit of Disney in there, that evokes the celestial ancestors of Mulan and, especially the Brizzi Brothers’ Firebird Suite from Fantasia 2000 with its playful sprite of nature. In fact, it was that subconscious connection that perhaps lead me to believe I was in for another kind of film altogether. I knew that Kells wasn’t a musical (save for one tuneful moment), and that it was going for a much more mature reach than the usual kids fare that the medium has foisted upon it, but the publicity and trailers didn’t shy away from selling the film as something of a folksy, sweet film that features a lively little Irish sprite.

It’s actually when she, Aisling, arrives on screen, approximately 20 minutes in when Brendan finds himself lost in the forest beyond the monastery’s wall, that the movie finds something of a groove, where neither the plot nor the visuals continue to outweigh the other, even if by this point I was still unsure as to some of the reasoning. As for the characters themselves, their designs reminded me of those that might be found in a short, and although the overall visual interpretation is a unique blend of multiple influences, there’s something vaguely familiar about some of the character faces here, especially in some of the supporting figures, some of which are just plain too “cartoony” (bizarrely, Dave The Barbarian came to mind).

On the soundtrack, the major voice cast member is Brendan Gleeson, a terrific Irish actor who was so effective in the very adult crime comedy In Bruges, and has also popped up recently in more related fare as an animated pal of Bob Zemeckis’ Beowulf and in probably his most well known Harry Potter role of Mad Eye Moody. He’s good value here, but doesn’t really seem to do much more than read his lines as required, in a way akin to a radio play or script read-through (it’s interesting to see some of the actors together in the supplements, which supports this theory).

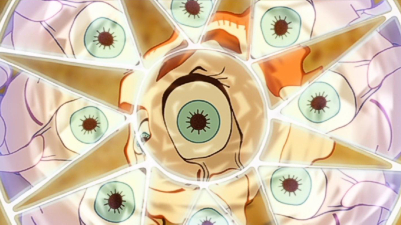

But Gleeson’s Abbot character is something of an enigma anyway, trying to do what he believes is right for his people while also being too strict and firm as a father figure to his young nephew Brendan, and something more in the performance might have read more depth into his thoughts: even a one-note character needs to have layers, and I was missing any real emotional connection or pivotal scene that addresses their relationship. Of the other cast, the rest of the voices do what they need to do without bringing anything particularly special to their roles, though young Christen Mooney and Evan McGuire, who has carry much of the film as Brendan, do very well even if it is ironic that Brendan is totally silent during a visually stunning sequence in which he faces off against the snake-like incarnation of the dark forces of the forest.

Ultimately, I found it rather hard to engage with The Secret Of Kells, mostly down to a plot where things just seem to happen, progressing from one moment to the next with only the threat of a Viking raid providing anything resembling an overall arc. That threat of war is ever present, but there doesn’t seem to be much explanation behind much of what goes on…or at least as far as I could understand. It’s often as if the characters are all in on what’s happening, but someone forgot to tell the audience. And it’s not as if I like simple-minded, easy to please moviemaking – far from it: I love films that weave between multiple narratives, flashbacks, dreams, and the like. Perhaps I missed one vital cue of dialogue that might have altered my entire perception of the film’s events?

As such, and despite the clear visual achievement, I must say that I found the “surprise” in its surprise Oscar nomination to be warranted: though it has a distinctive look, at times I was so puzzled at why things were happening, though never did I particularly want it to end out of frustration. In this respect it reminded me of a Japanese manga anime, with a baffling storyline that suddenly comes together, only for the big monster to come along and blow everything up. Kells isn’t as incoherent as that: the growing threat from the Vikings means that, at the very least, the story is heading in a certain direction and will reach a resolve.

I’m absolutely sure a second watch would clarify plot points and some of the reasoning, but I can’t say I’m jumping to revisit this magical forest. If there was inherent symbolism on display, it flew right over my head, and often it felt as if there was a layer of storytelling missing, either in the form of some much needed backstory we should already know or from a context that might have been shown up front and explained in a prologue scene. I hate to say it, but I could have used some narration here or there: I’m no dum-dum, and a narrative track usually indicates a story that doesn’t quite tie together, but the density of Kells for anyone not familiar with the subject, often made it a struggling 75 minutes for me.

I truly suspect that, if you know of the Book Of Kells and its place in history, you’d have some better standing on which to appreciate this picture, but for those without that knowledge, there’s precious few access points offered for us to gain entry to that world. “You can’t find out everything from books, you know”, someone says at one point, to which the answer is, “Haha, I think I read that once”. In this case, I’d suggest you do pick up a book and learn a bit about the subject before sitting to watch The Secret Of Kells. Although I really wanted to enjoy it, I couldn’t find a way in and only wish that, by the end of the movie, I’d learned just what the secret was.

Is This Thing Loaded?

In so far as being able to appreciate the final movie, it’s a rare case where I might suggest that one actually begin with the supplements. The first of these you’ll come across is the enclosed booklet on the origins of two of the characters from the feature, but more on that below. As a new imprint, New Video presumably doesn’t have a ton of upcoming titles to throw at us, and so it’s refreshing not to have to wade through any preview trailers in order to get to the main menu. The first supplement on the disc that you’ll want to check out is the Notes From The Master Illuminators: Audio Commentary with director Tomm Moore, co-director Nora Twomey and art director Ross Stewart.

As you’d expect for a truly independent production that had to scrimp and save funding from a variety of countries, the participants have a love for the subject and their film that makes it a much more personal prospect than a big studio picture, and sitting with them to hear about the production is extremely interesting. Some of the predicaments I had with several aspects in the storytelling sound as if moments were lost in the editing process both through the ten year development period and some ten minutes in the final cutting of the film, and I wonder if the crew were too close and familiar to the production when a fresh eye might have drawn attention to material that should have stayed in. But as commentaries go, this is an insightful exploration of the making of a film that you could wish for, and gives a fresh appreciation for the achievement at least.

The Voices Of Ireland, as you will imagine, goes behind the microphone to offer near eleven minutes of footage from the vocal recording sessions. This isn’t a featurette per se, but a collection of video camera snippets that finds Gleeson and the other main performers going through their lines and offering occasional variations. It’s interesting enough, particularly to see the actors reading against each other instead of providing multiple takes on any given line, but it’s not been edited in any particular fashion, being a bit like a copy of a raw camera complete with jump cuts and, be aware, a lack of audio sweetening at a couple of points when Gleeson shouts, creating audio distortion that could pop your speaker tweeters.

Again not so much as a featurette as a collection of clips, Pencil To Picture, Part One and Part Two provide around nine minutes of storyboard to final film comparisons for two sequences, which show a lot of the intricate planning in the backgrounds was laid out from the beginning. Some instances of pencil test animation hold up the interest, but that so much of what it shown is basically from the finished movie, there’s not so much we haven’t already just seen to be found here. A nice touch at the 2009 Academy Awards was having the “stars” of the Best Animated Feature nominations expressing their excitement in a press junket scenario, and Aisling At The Oscars plays out one of her reactions, short but sweet at under 20 seconds.

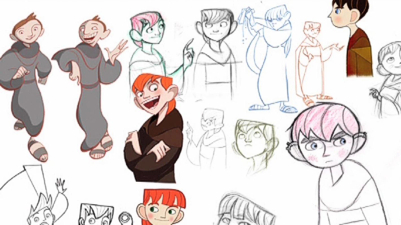

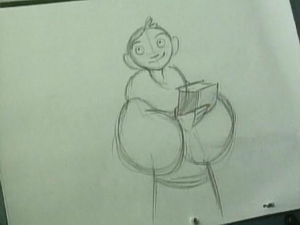

Much more substantial is Moore’s Director’s Presentation, a 27 minute grouping of production images and narration that offers a lot of background on the film project itself, from the inspiration of the Book Of Kells itself – with a little but much needed explanation of what that actually is – and peeks at early development that went for a much more traditional approach with extremely different character designs, to concept illustrations, scene explorations, characters, locations, props, color scripts and more. It’s an interesting video gallery presentation which is only added to by Moore’s always light-hearted, sincere and enthusiastic comments.

Following on from this, a four minute Early Concept Trailer expands on that development material, presenting footage from when the film went under the working title of “Rebel” and had the earlier character designs. In an Optional Commentary on this teaser, director Moore dates the clip as coming from 2000, right at the beginning of their production adventures, and acknowledges the vast differences in story and visual approach. It has a rougher, looser translation to the animation, but there’s still some wonderfully visual stuff in here all the same, and another tantalising glimpse into material that seems to have been dropped during the visual overhaul to what the film became.

Finally, a Theatrical Trailer is actually more of a post-festival screenings celebration of the film’s critical and Oscars recognition, running like a mysterious teaser that plays up the film’s mystical and fantasy elements without setting up much plot, focusing instead on Aisling’s song and a final plug for the Blu-ray and DVD. I don’t know if an actual full preview exists, but I’d be intrigued as to how the distributors marketed The Secret Of Kells to audiences used to more “easy going” animated films. As it stands, though, being enigmatic about the movie is about the only way I could think of selling it too, and as such it’s a nice full-circle kind of way to round out the unexpectedly strong supplements package in this set.

On the included standard definition DVD, the exact same contents, from the movie and commentary, to the development materials and trailer are replicated, right down to the same basic main menu, allowing regular DVD viewers the chance to future-proof their purchase but still enjoy all the bonus supplements ahead of upgrading to high definition.

Case Study:

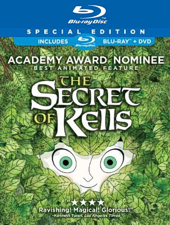

A major selling point for The Secret Of Kells is that Best Animated Feature Oscar nomination, and it’s prominently placed as the filmmakers’ proud badge of honor multiple times all over the cover art, which otherwise re-uses the theatrical teaser of Aisling peeking through the forest leaves. The excitement of a Blu-ray release seems to have hit the designers, though: almost a fifth of the top of the glossy embossed slipcover is just an all-blue banner and the BD logo, though it’s more reserved and appropriate on the sleeve underneath. The enclosed The Secret Of Kells: Origins booklet provides excerpts from the “prequel graphic novel” of the film (which possibly includes additional material), namely Aisling’s story (the same dialogue as opens the film) and Brendan being saved from the Vikings as a baby.

It certainly feels more than just the usual insert, even despite the small BD case size, though at this scale there just isn’t the ability to really marvel at the extraordinary artwork, impressive as it is, but it’s a nice addition that thankfully doesn’t feel like a promo for the graphic novel itself. The disc art might well have gone for another poster treatment, since having Aisling’s eyes either side of the center hole gives her an odd third eye, or perhaps the image could have been moved up so that she at least she could have been appearing to peer over the hole? In any event, it’s nice to see the poster art used consistently throughout the package and in the menus, though be sure to check which disc you’re inserting into your player: there are no differentiating marks other than the small format logos to see which is which.

Ink And Paint:

As a digital creation, even by an independent studio, animation basically looks about as good as it gets under any budget these days. Kells is no different, and it’s pleasing to note that the film’s major strength, its unique meshing of visual styles, is presented with the utmost clarity that Blu-ray can provide, giving much opportunity to pick out all the remarkable background details. On the included DVD, I did notice quite a lot of color banding on shaded characters, which can be quite distracting when they move about and the blocky color goes with them, but this isn’t so noticeable on the BD, and otherwise everything looks as we’d expect in its native 1.78:1 ratio.

Scratch Tracks:

From the opening moments of the movie, I had to work hard to pick out some of the very first lines of dialogue. It’s a wispy narration from the fairy Aisling, provided to create an air of fantasy, but the echo, hollowed affect and reverb had me straining to understand what was being said enough for me to bump up the center speaker channel to almost maximum. With that volume boost in place, I found the rest of the dialogue in the early scenes, which isn’t helped by quite a forceful amount of bass in the music, to be much more audible, though it was quite a surprise for such a dialogue-heavy film to have them buried so deep in the mix. The BD’s DTS 2.0 and 5.1 tracks are swapped for Dolby Digital in both variations on the DVD. English subtitles are also offered on both discs.

Final Cut:

The extremely high class achievement of The Secret Of Kells as an independent production going against the grain to do something different with animation surely outweighs the final result in terms of entertainment, at least in the eyes of this reviewer and his total lack of knowledge on the subject. However, whatever my own shortcomings in coming to the world of Kells, surely I can’t be the only one that hasn’t got a grade A level wealth of background to hand? As such, it’s the filmmakers’ obligation to make sure that all newcomers should be able to enjoy their work as much as the next viewer.

But I don’t think I’m going to be the only one who finds they need an extra bit of information here and there to fully appreciate the film. Let me be clear and state that I in no way thought it to be unworthy of a watch, and even if the Oscar nomination remains a surprise and Tomm Moore’s direction doesn’t always gel, this is obviously the result of some very talented artists. Visually it does its own thing with confidence and a fine execution, but The Secret Of Kells is perhaps best reserved for the rental list, where a test run will prove if it’s one you need to add to your shelves on a more permanent basis.

| ||

|