Celebrating the beginning of the international home video roll-out for Disney’s return to hand-drawn animation The Princess And The Frog, Jeremie Noyer joins a roundtable interview directors John Musker and Ron Clements about how they went about bringing the magic back to the Mouse House!

Born in Chicago, Illinois, John Musker first began drawing while in grammar school and knew by the age of 8 that he wanted to become an animator. Inspired by such Disney classics as Sleeping Beauty and Pinocchio, as well as Bob Thomas’ primer The Art of Animation, he developed a thorough understanding of the animation process. His fascination with comics, cartoons and Mad Magazine further stimulated his desire to draw.

At Loyola Academy, a Jesuit high school in Wilmette, Illinois, Musker became a cartoonist for the school paper. His special brand of caricature, which included outrageous sketches of teachers and school celebrities, quickly caught on. This preoccupation with caricature and cartooning continued throughout his college years at Northwestern University, where he majored in English and drew cartoons for The Daily Northwestern.

Following graduation from college in 1974, Musker put together a portfolio and set out for California to pursue a career as an animator. Initially rejected by Disney, he enrolled at the California Institute of the Arts the following year to master his craft. After completing his first year, which included a summer internship at the Disney studio, he was offered a full-time job as an animator. This time Musker turned it down, opting instead to complete the second year of his training.

In 1977, Musker started work at Disney, where his two training tests were enthusiastically received and he began as an assistant animator on The Small One. He also animated on The Fox and the Hound and did story work on The Black Cauldron.

Born and raised in Sioux City, Iowa, Ron Clements traces his interest in animation to his first viewing of Pinocchio at the age of 10. As a teenager, he began making super-8 animated films, including Shades of Sherlock Holmes, a 15-minute featurette he animated single-handedly. Shades won critical acclaim and led to a part-time job as an artist at a television station, where he animated commercials for the local market. Several years later, Shades helped Clements get a job at Disney and also served as the inspiration for The Great Mouse Detective, which he wrote and directed with Musker.

After graduating from high school, Clements came to California to try his luck at animation. Because there were no openings at Disney, he worked for several months at Hanna-Barbera while studying life drawing in the evening at Art Center. With persistence and determination, Clements was finally accepted into Disney’s Talent Development Program, a training ground for young animators. His self-taught experience and ambition made up for his lack of formal training.

After successfully completing the training program, Clements served a two-year apprenticeship under Disney legend Frank Thomas. He quickly progressed through the ranks from inbetweener to assistant to animator-storyman. His credits include Winnie the Pooh and Tigger, Too, The Rescuers, Pete’s Dragon, The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron.

Ron Clements made his writing-directing debut with John Musker on the 1986 Disney animated feature The Great Mouse Detective. Following that, he successfully pitched an animated version of the classic Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale The Little Mermaid, which reteamed Clements and Musker as co-writers and co-directors and became one of the studio’s greatest artistic and commercial achievements. Musker and Clements went on to write and direct two of the funniest and most memorable animated features ever – Aladdin and Hercules. Clements and Musker’s next project was Treasure Planet, the swashbuckling intergalactic adventure based on the classic novel Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Of his successful partnership with Ron Clements, Musker says, “We’re both relatively agreeable Midwestern types, and we each have slightly different strengths and approaches. Ron is more structure-oriented and makes sure that the overall story doesn’t disintegrate during the course of too many rewrites. I tend to be more concerned with specific details and gags. We constantly go over each other’s scenes and drafts and add new ideas and suggestions in the process.”

Roundtable Interviewer: What is the reason you picked New Orleans as the setting for the story? Does ‘Katrina’ have anything to do with it?

Ron Clements: It was actually John Lasseter’s idea to set this story in New Orleans. And he wanted to do this several years before Katrina. The reason was he loves that city and thought it would be a great location to set an animated movie. When John became head of Disney animation in February of 2006, he asked John Musker and myself to consider the idea of setting the fairy tale The Frog Prince in New Orleans. We pitched him the story that became the basis of the movie. This was about eight months after Katrina. John Musker and I visited New Orleans for the first time shortly after that and we saw the terrible aftermath of Katrina first hand. We definitely wanted to do whatever possible to help the city recover.

RI: Why did you chose the story of The Frog Prince and twist it the way you did?

RC: We liked the idea of doing an American fairy tale and the setting suggested using elements of Voodoo, having an African American heroine and the approach to the music. The big twist of having our heroine turn into a frog once she kissed the frog, came from a children’s book called The Frog Princess by E.D. Baker, which Disney bought the rights to in 2003. Many of the characters in our version including Mama Odie, Tiana, and Ray the Cajun firefly were inspired by actual people we met in our research trips to New Orleans. Other twists came from the basic desire to use iconic fairy tale and Disney archetypes but do a spin on them to make the movie fresh.

RI: How important is John Lasseter for the world of animated pictures, and for yourself? Is he already up there with Walt Disney?

RC: Everybody’s different, but John Lasseter is inspiring, gives great story notes, and has a huge passion and enthusiasm for animation. It’s hard for me to imagine anyone better to work for.

RI: How much time does it take to complete a movie like this? From the initial sketches and ideas to the final version?

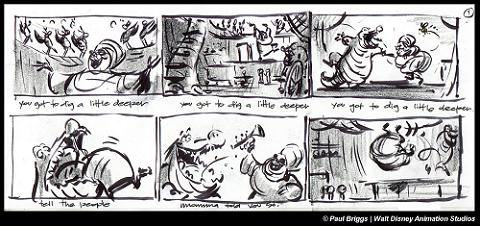

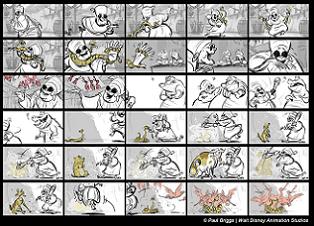

RC: We pitched the story of this movie to John Lasseter in March of 2006. We started working on our first draft of the script that summer. Visual development started soon after that and songs, voice casting and storyboarding began in the fall. Experimental animation began early in 2007 with layout and production animation beginning in the spring. Color soon after that. All in all, about three and a half years from beginning to completion, which is actually pretty fast for this kind of film.

RI: I was told by Mark Henn that the design and personality of the different characters were set during a weekend at a hotel resort. How and why did you choose that way of processing to create the characters?

John Musker: Sometimes when we are developing these films, sequestering ourselves in a different environment can provide a focus away from other distractions. There’s no “right” way to do it but this one was very collaborative and helpful I believe. And then you stroll out of doors in this beautiful setting of Ojai and wish you were playing golf there.

RI: Given the in-depth story development process Disney animated features go through how different is the film from what was first pitched?

JM: This film is fairly similar to the first outline we pitched to John Lasseter four years ago. In terms of differences, the character of Tiana’s father assumed a bigger role as we made the film and we tied her passion for her restaurant more into her father’s dream. Our earlier version had Louis as a gator who was actually a human, an accountant who dreamed of becoming a great jazz player. Facilier gave him the ability but double crossed him and turned him into a gator. A few of the names changed. Dr. Facilier was originally Dr. Duvalier but we didn’t want to confuse him with the ruler of Haiti with that same name. A few of the song ideas evolved as well. Louis’s song originally was about how much he loved jazz. We eventually thought it would be fun to have all three characters sing and highlight the differences in their characters and their aspirations.

RI: How many endings did you have planned out for The Princess and the Frog and can you share some ideas that you had for other possible endings if possible?

JM: The ending of the film is the one we originally planned. The idea that they got married as frogs, and then kissed and transformed back was in an earlier script for the movie that Greg Erb and Jason Oremland wrote. We liked that twist and always intended to use that. Musically we thought there would be a final reprise in her restaurant, but we discussed a number of different ideas. It was John Lasseter’s thought to reprise Down in New Orleans and have Tiana sing a very powerful version of it. We liked his idea. It put her back at the center and showed how she had been changed by the Prince to publicly sing such an emotive number. We did consider having a wizard’s duel in the climax between Mama Odie and Facilier that we didn’t do because the main characters were too far outside of it. We also had an ending where Facilier’s magic backfired on him and he was turned into a fly which was gobbled up by a frog. Also we had a plan for a “plague of frogs” to descend on Mardi Gras, an outgrowth of a story idea in which Facilier proposed to Big Daddy a contest for the best frog dish, in an attempt to get his wayward frogs rounded up from the bayou.

RI: How much did Cinderella impact on the making and storyline of The Princess and the Frog.

JM: Certainly Cinderella was one of our influences both in the broadest sense in that this is a “Cinderella” story, an underdog tale, a story of a girl who gets to trade her working clothes for a beautiful ball gown, and in some of the more specific imagery when we had our Mardi Gras masquerade Ball a la Cinderella’s ball. We thought of Mama Odie as our bayou fairy godmother. Our designers like Ian Gooding, and particularly Lorelay Bove, are big fans of Mary Blair the brilliant designer who had such an impact on the Disney animated films of the Fifties. I saw Cinderella a number of times when I was preparing to attend CalAts to study animation and I marveled at how entertaining it was and still is.

RI: Films like Shrek appealed to many different cultural references. Princess and the Frog appealed to so many references taken from Disney history, but in its own way. How did you use references?

RC: I love Shrek, but in this movie we were deliberately trying to stay true to the period and avoided many modern cultural references. As you say, we did have a number of “callbacks” to earlier Disney films, not so much for comedy, but as a way of acknowledging the Disney legacy and comment on this movie places in it from a slightly new perspective.

RI: There are a number of ‘in house’ jokes in the film – streetcar A113, Firefly Five Plus Lou – do you each throw these in, or is one of you the chief pun artist? And which is your favorite joke?

JM: I attended Cal arts with John Lasseter and Brad Bird among my many talented classmates. We studied animation in room A113, so I always wanted to put a reference in one of my projects to acknowledge my kinship with them. The Firehouse Five reference came from both I think. Although, I can’t remember if it was Eric Goldberg who thought of the “plus Lou” variation a la “plus Two”. We both saw Frank Thomas play piano and wanted to do a shout out to him. I wanted to do caricatures of some of our coworkers as characters, so the prince’s group of female admirers are actually based on Ali Norman, Jen Kilger, Shanda WIlliamson, Elissa Sussman, and Lorry Shea, all ladies who worked hard and well on this production.

RI: It is the first time that one of your films is being released on Blu-ray? What are for you the benefits of this support compared to a standard DVD

RC: The picture quality is impeccable. Better than most people will see in a theater. And the extras are a lot of fun. John and I were particularly excited that the Blu-ray contains the entire movie in rough pencil test form as well as color. For animation buffs, this is a great opportunity to see the process in a way few get a chance to.

RI: Blu-ray is sometimes described as TOO high res, actually detracting from the quality of some films. Are you happy with the Blu-ray version? Which do you prefer?

JM: I like the Blu-ray version and the earlier ones they did of Pinocchio and Sleeping Beauty are stunning and I would recommend the Blu-ray versions to anyone looking for the premium version of the film. The Blu-ray also has a feature where you can watch the entire film in rough animation pencil drawings so for students and fans of animation it’s a unique opportunity to see the film as it was before completion.

RC: In the case of modern animated films, all the final color work we do is in a very high definition digital format. This is the way the film is projected in digital theaters and is the ideal way we intend the film to be seen. Film resolution is actually not capable of producing all the subtleties of color that digital can. In that respect, Blu-ray is the closest thing possible to seeing the film as intended.

RI: Was this movie a reaction to the new 3D CGI hype of making movies?

JM: Not really. We love hand drawn and we have enjoyed the CG films as well. We just thought this story with its organic setting was ideal for the warmth and expressiveness of hand drawn animation.

RI: Do you find a difference in the way people identify with this style of animation, as opposed to the newer, digital process? Do you think, with the advent of 3D technology hand-drawn animation will still have a place?

RC: I certainly hope hand drawn animation has a place. The Academy Award nominations for best animated feature were interesting this year in that they contained two stop motion films, (Coraline and The Fantastic Mr. Fox), one digital film, (Up), and two hand drawn films, (The Secret of Kells and our movie). It’s nice to see this kind of diversity. Really, they’re all just different kinds of paint brushes and I don’t think it’s necessary for the same paintbrush to be used all the time on every movie.

RI: Given its inherent 2D starting point, do you think hand drawn animation is at a disadvantage in the looming 3D world?

JM: Interesting question. They have actually taken Beauty and the Beast and converted it to 3D and we’ll see how that is received. I don’t believe all of live action is going to go the 3D route. It remains to be seen also if audiences will feel that 3D is a passing fancy or a change to stay.

RI: Why was The Princess And The Frog another hand drawn animated movie and not a computer animated movie?

RC: All the movies John Musker and I have directed were hand drawn films. We love this medium and were very sorry to see Disney abandon it a few years ago. Fortunately, even though John Lasseter has achieved so much success with computer animated films, he loves hand drawn animation just as much as we do. When he was put in charge of Disney animation four years ago, he very much wanted to bring back hand drawn animation. This story seemed an ideal vehicle for that as a classical musical fairytale and the lushness, romance, warmth and magic of the setting.

RI: How did you feel being the directors of a movie that would bring hand drawn animation back in the spotlight?

RC: We love hand drawn animation and were very excited to see it return to Disney. And it was great working with an all star team of artists and animators and creating a venue where they could showcase their amazing talents. The skills involved with this particular art form are rare and take a long time to learn how to do well. They’ve tended to be passed on through mentor/student relationships where veterans pass on their knowledge to younger apprentices. That was true on this film as well and it was exciting to see a new generation fresh out of art school develop and contribute strong work for the movie.

RI: The Princess and the Frog was a mixture of veterans of hand-drawn animation and newcomers. How did that affect team chemistry?

JM: It was a good mix. The veterans were able to mentor the younger animators and those younger ones and their great skills bode well for the future. We ourselves were trained by the “Nine Old Men” the Disney veteran animators. Ron worked with Frank Thomas who had animated the Dwarves and Bambi and Captain Hook among others. I had worked with Eric Larson who animated the cat Figaro in Pinocchio and Peg in Lady and the Tramp. One of the best ways to learn animation is in this type of arrangement of master and apprentice passing on the craft. The youthful enthusiasm of the newcomers was a reminder of the joys of bringing drawings to life, a special skill that few have mastered but one of the most rewarding combinations of sleight of hand, draftsmanship, acting and entertaining.

RI: What changed in terms of techniques or way of working on a 2D movie since The Little Mermaid or Aladdin?

JM: The essential techniques are quite similar. Mermaid was the last feature to use cells and have the characters painted with real, rather than digital, paint. On this film we did the character animation on paper as we did on Mermaid and Aladdin. But for the first time we did our effects animation, namely the ripples of water the magic, the shadows, paperlessly. They were drawn with a stylus on a pressure sensitive tablet.

RC: There are several new innovations. In terms of layout, (the staging, lighting and cinematography of the movie), we did something new on this film where we did “layout animatics” of each sequence with all the camera moves, lighting, and basic blocking of characters, before any animation was done. This was something John Lasseter brought over from Pixar and was a great tool in helping us pre-visualize the film more specifically than ever before. We also had new color processes which allowed us to view scenes in final color while still being able to make significant changes much more easily. We experimented with paperless animation on this movie, with animators drawing on a digital tablet, but found glitches in the process we couldn’t overcome. But we did actually do our effects animation (water, smoke, magic, etc.) with paperless animation.

RI: Which scene are you most proud of ?

JM: The song Friends on the other Side was very very complex in terms of the effects animation, all that magic, and the tarot card animation, the Voodoo doll chorus and the choreography of all. We are happy with the way it turned out and the fine work Facilier animator Bruce Smith did, our choreographer Betsy Baytos and dancer Dominique Kelly did, and the amazing effects work of Marlon West and the color of Ian Gooding.

RI: What defines a great animation movie in your opinion?

RC: Great characters, a great story with a satisfying ending, and an interesting world where you can really enjoy spending an hour and a half. And finally, you want all of this presented in as fun and entertaining way as possible.

RI: What is the most difficult aspect of creating a character?

RC: Good characters are the heart and soul of these movies. It’s important that the characters become real to the audience, that the audience relates to them identifies with them, that the characters feel like real people that they know. This is true whether the characters are humans or alligators and fireflies. We want the characters to have depth and dimension and we work very hard to achieve that. A lot of this happens in the scripting and storyboarding process. But casting the right voice actors is extremely important. And finally, casting the right animators, who are really good actors in their own right, is essential in pulling this off.

RI: What inspired you to create the characters?

RC: Many of the characters were inspired by actual people we met in our research trips to New Orleans. Tiana was greatly inspired by Leigh Chase a legendary New Orleans restaurateur who started as a waitress and opened the famed Dookie Chase restaurant. Mama Odie was partly inspired by Ava Kay Jones, a Voodoo priestess who has a snake she dances with, and Colleen Salley, an irascible New Orleans storyteller. Dr. Facilier is based on the New Orleans “Bokur”. These are loners who’ve broken away from the Voodoo religion, made pacts with dark Voodoo spirits and sell magic for money. As Ava Kay told us “these spells almost always backfire, as easy answers are really no answers at all.”

JM: When we began the film we read a number of treatments that had been written over the years when the studio was considering doing an animated version of The Frog Prince. One of them by Dean Welins and Chris Ure, two story artists, who had the idea of a firefly who fell in love with the Evening Star. We love that idea and thought it fit the theme of love conquering even the most impossible obstacles. We thought he should be a Cajun. While we were down in New Orleans researching the movie, we went on a tour of the bayou and had a gap toothed Cajun tour guide who fed alligators over the side of the boat. His name was Reggie and when we later wrote the script we had him in mind. We also thought he could sing a wistful Cajun waltz to his star. The name Evangeline came from a Nathanial Hawthorne poem about a Cajun woman named Evangeline who wandered in search of her lost love.

RI: How much impact do the people you cast as voice actors have on the characters and the story?

JM: They have great impact. We often hire actors who can improvise in character and certainly Jim Cummings and Anika and Bruno could all do that. Tiana got her dimples and her left handedness from Anika. Bruno has a big handsome toothy smile that got grafted onto Naveen and the space in Facilier’s teeth came from Keith David.

RI: Were there any complaints from the subjects about how their caricatures looked?

JM: Lorry Shea the feisty redhead occasionally complained that I made her look too short, but she is short and that’s part of her dynamic appeal. At least that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

RI: The Princess And The Frog sees the creation of the first African American Disney princess, did you think it was about time?

RC: In retrospect, it was certainly about time. But we didn’t approach this movie with that as any kind of agenda. John Lasseter suggested taking the fairy tale The Frog Prince and setting it in New Orleans. The idea of making our heroine African American simply grew out of the setting and that was an integral part of the story we pitched to John in March of 2006. We all thought it was a great idea. But it wasn’t until later that we fully realized the importance of this in the African American community.

RI: What impacts have you seen?

RC: We have been thanked personally by a large number of African American Moms who have been thrilled to see a Princess that looks like them and their daughters up on the big screen. At times these have even been tearful and it’s been very rewarding.

RI: It’s been reported that there were some changes to the title and character names as a result of Tiana being the first African-American Disney Princess. How much truth is there to that? And did that lead to new pressures?

RC: The original title of the movie was The Frog Princess which was the title of a children’s book by E.D. Baker which Disney bought the rights to in 2003. After a bit, we decided to change the title to The Princess and the Frog. This is not unusual. Many of our films have undergone title changes along the way. Also, Tiana was originally named Madelyn (nicknamed Maddy), in our original treatment. But we changed it to Tiana, which means “Princess” in Greek. Once again, name changes happen a lot as stories develop. But we did feel this film was under an unusual microscope as it developed and that did create a certain kind of pressure. Our goal was always to try and be as sensitive as possible while always staying true to the story we wanted to tell.

RI: Breaking with the oft-criticized tradition of the damsel in distress being rescued by the shining hero, did you set out to turn Tiana into an empowerment figure for young females of today?

RC: We always liked the idea of Tiana being a different kind of Disney Princess. She’s the first one to have a job and a career goal. We created the character of Charlotte to poke fun at some of the Princess stereotypes and to contrast with Tiana. We thought of Tiana as being a kind of modern Princess.

RI: I love the character of Mama Odie. She seems to be the opposite of Facilier, a kind of a “light” fairy opposed to the “dark” lord. Did you ever think of a more direct confrontation between the two of them?

JM: We did consider a battle between the two in the climax of the film, where light overcomes darkness. We couldn’t find a way to make it work. We were even considering “musicalizing” it. It would have been fun.

RI: How did you come to the idea of giving life to Facilier’s shadow?

RC: We referred to Dr. Facilier as “The Shadow Man” from the very beginning. But it was an early visual development drawing by Sue Nichols that inspired us to give his shadow a life of its own.

JM: Early on in our script Ron called Facilier the Shadow Man, based on some of the bokkurs of New Orleans, fortune tellers and voodoo practitioners who would sell you charms to help your love life or curse your enemies. Sue Nichols Maciorowski, a wonderful visual development artist, came up with the idea of the shadow having a life of its own. She did drawings that showed the shadow reacting independently of the villain. She also did a drawing of Facilier dancing a duet with his shadow. Both of these ideas seemed very visual and fun to do in animation.

RI: How did you make the villain Dr. Facilier different from other Disney villains?

JM: He didn’t want to rule the world like some villains. He was a bit more down on his luck. His interaction with his own shadow was different than others. He is very charismatic and a showman and that made him fun to animate.

RI: How is it possible for Tiana to be Charlotte’s best friend as their characters are completely different?

JM: I think it’s possible for best friends to be different. Although Tiana is repelled by kissing a frog, she is still intrigued by fairy tales. As you see in the opening, they are both interested in the story Eudora is telling. They both wear princess crowns. Tiana’s harder life leads her to lose some of the fun she had in her life as a child. Tiana enjoys Charlotte’s exuberance even though she is by nature more reserved. Sometimes people find in friends or partners people who are very different and who do things they are might like to do but are too inhibited to pursue.

RI: The film really takes off once the animals become the stars, were you aiming for that?

JM: That wasn’t the intention, but the “entertainment value” does seem to expand once Tiana becomes a frog. There is a greater possibility for visual humor, caricature and fun when we have the comedy inherent in people transformed into the unfamiliar. Our challenge with the opening was to attempt to get you involved enough in Tiana’s plight, and in Naveen as a character that you root for them in the remainder of the story.

RI: How did you come up with the musician alligator? What inspired you to create him?

JM: Alligators are native to Louisiana and we saw some in the bayou when we visited on a research trip. The big scale seemed a fun contrast to the smaller scale frogs. His musical inspiration is the great trumpeter and New Orleans native Louis Armstrong. The original concept was that the gator was a human who came to Dr. Facilier wanting to be the greatest jazz player of all (he couldn’t play a note). Facilier made him a great jazz player but also changed him to a gator in the process. This was later simplified when the film got too long.

RI: There’s the influence of Louis Armstrong in Jungle Book (which he was once intended to be part of), in Aristocats (Scat Cat), and then you created Louis, the alligator. How do you explain that success of the famous trumpet genius in animation?

JM: He is one of the greatest entertainers in American entertainment. He was so emotive. And he created an indelible impression with both his soulful trumpet playing and his jazz voicing and phrasing, with his singing, equally distinctive in that powerful sweet growl, and in his look as well, with the sweat, the handkerchief, the smile and the squint. He was an icon both aurally and visually.

RI: When did Randy Newman became part of the project?

JM: Very early in the process. We suggested using Randy because of his feel for Americana and New Orleans. John Lasseter liked the idea. The script hadn’t been written yet but we showed randy a visual outline and pitched him the story and explained how we thought music would work in the film.

RI: How important was it for you to put great songs – that really stick in people’s minds – in the movie?

JM: We love musicals and find that songs are a great way to show the characters’ emotions as well as be fun for the audience to see performed in a bigger than life way. Music is an important part of New Orleans and the fabric of that city and felt natural. We attended the yearly jazz festival when we were doing research for the movie and thought we wanted to capture the different musical styles we heard there: Gospel, Dixieland, Swing, Zydeco, etc. Randy Newman spent boyhood summers in New Orleans and he seemed ideal to bring that to life.

RI: A good part of the movie are Jazz songs, sort of logical considering that the story takes place in the birthplace of Jazz itself. What do you think of other animated movies from other studios, like the recent How To Train Your Dragon, where the characters don’t sing a single song and yet happen to have such a great audience at the cinemas?

RC: I enjoyed How To Train Your Dragon very much and certainly don’t think an animated film needs to have songs in order to be good. But musicals are a lot of fun to do and I think songs and animation work together very nicely.

RI: I know you’ve made several more films together but how difficult is it to direct a movie with someone else?

JM: It helps that Ron and I co-write the script together. There we have a chance to literally ‘get on the same page’ and make sure we are trying to tell the same story. We have different strengths that we try and bring to bear. Ron is more structure oriented and is good with emotion. I lean towards the comic and action set pieces.

RI: What was your most memorable experience working on The Princess and the Frog and what was the most difficult part for you in creating this film?

JM: Our trips to New Orleans were very memorable and meeting great people down there like Coleen Salley, a salty septuagenarian (white woman) a raconteur and full fledged “character” who influenced our writing of Mama Odie. We also met Leah Chase, a great lady who runs the Dooky Chase restaurant with her husband. She is in her eighties I believe, still works, started as a waitress, and is an amazing combination of warmth, gentility, and grit. She inspired some of our approach to Tiana. We also recorded Dr. John down there and got to ride on a float in Mardi Gras. The toughest hurdle was when Ron Clements, my partner, discovered he had to have open heart surgery because of blockages in his arteries. He recovered amazingly well but at the time we had no idea how debilitated he would be.

RI: Just like in Miyazaki’s films, food seems to have special importance in your movies – crab soup, Silver’s stew, Tiana’s father and her gumbo. Is it a way of inviting all our senses to the feast when enjoying a good animated film, with great visuals, great music, etc? Do you taste specialties when you go on research trips to prepare your movies?!

RC: Not always. In fact, we tended to avoid seafood while we were working on The Little Mermaid! But one of the great perks of working on Princess and the Frog was getting to spend quite a bit of time in New Orleans and enjoying some of the most delicious food I have ever tasted. People are obsessed with both music and food in that city and we knew we wanted both of those things to play a big part in our movie.

RI: The sequence in the restaurant has a distinctly different animated style, what was your thinking behind that?

JM: Because it is her fantasy, it seemed like it gave us the opportunity to style it different from the rest of the film. Sue Nichols Maciorowski, a wonderful visual development artist, brought the work of Aaron Douglas to our attention. He was African American and a member of the Harlem Renaissance and he produced amazing drawings and murals in a Deco style. We thought having an illustration in that style, which was her starting point for her restaurant come to life, would be graphically exciting. At the film’s climax, when Facilier offers to make that dream real, we could then take those stylized images and make them more dimensional, which might make them seem that much more enticing to her.

RI: You show a great passion for the comic book world. What do you think of the recent big screen adaptations, like 300 or heroes of the Marvel and DC Universe or the Batman saga remake?

RC: Both John Musker and I are big comic book fans, especially DC and Marvel comics from the sixties, the silver age, when we grew up. I loved Richard Donner’s Superman movie, Sam Raimi’s first two Spider-Man movies, as well as many others. I was blown away by Christopher Nolan’s recent Dark Knight movie and felt it reached a whole new level. I liked 300 and am a big fan of Watchmen the graphic novel. The closest we’ve ever come to a comic book movie was Hercules who we thought of as one of the first superheroes.

RI: Are there more movies coming up using these old techniques?

JM: The studio is currently doing another hand drawn animated feature. It is the further adventures of Winnie the Pooh. We are not involved with that. We are however hoping to do another hand drawn feature. We are in the very early planning stages and hope to get it moving forward.

RI: Do you already have an opinion on Disney’s next movie Tangled? Have you seen anything about it yet?

JM: It will be spectacular. It features songs by Alan Menken and Glenn Slater. Glen Keane (as executive producer) is striving to push the boundaries of CG to more looseness and expressiveness in the characters. You will enjoy it.

RI: What can you tell us about your next project?

JM: It is “in development” as they say. We are exploring a number of ideas, all of which we envision as hand drawn. The studio does have Tangled coming in November in the States, an adventure based on a fairytale with songs by Alan Menken, and directed by Byron Howard and Nathan Greno that is being done in CG. Glen Keane the exec producer is trying to get more of the looseness and expressiveness of his 2D animation into the CG animation. It is looking really promising.

RI: You started working for Disney from lowest to the highest levels of the organization. What does that experience feels like?

JM: It had been a fun thirty three years. I got excited about animation 37 years ago when I heard the great Warner Brothers director Chuck Jones talk about animation as a field in which you were always learning no matter your age. That made it sound appealing to me and he was right. You always feel like there’s so much to learn still.

RC: I’ve been at Disney thirty six years now and the time has gone by amazingly fast. But before that, I was a huge Disney fan and dreamed of working at the studio from the time I saw Pinocchio at the age of nine. Early on at the studio, I got to work as an apprentice animator under Frank Thomas one of Disney’s legendary nine old men. Since then, I’ve seen many many changes at the studio and in my own career as well. But I was originally inspired by the obvious passion, creativity and artistic integrity Walt put into his movies. He cared very deeply and wanted his films to be of the absolute highest quality possible. I’ve carried that with me and always wanted to do the same. I’ve always felt very lucky to work at Disney. For me it’s always been a dream comes true.

RI: Speaking from personal experience, how does it feel to have shaped so many people’s childhoods with your movies?

JM: It is amusing to us to, for example, be introduced to young girls who have the name Ariel or Jasmine. Certainly as we promoted this film many people of both genders mentioned how much they liked Little Mermaid and how much a part of their childhood it was. Certainly with the advent of home video and the opportunity to see these films multiple times, and with the nature of children being such that they enjoy repeating those experiences, the films have been watched endlessly, the way we as children sometimes played records. I feel very lucky to have been able to work on something that has lasted this long and hopefully will continue to find audiences. The wonderful music of these films is a big part of their staying power and Howard Ashman, were he alive today, would be thrilled I think to see his work make such an impression on people.

RI: You have created some terrific and beloved characters, do either of you have a favorite?

RC: It’s tough to pick favorites. It’s like ranking your children. But I’ve always been particularly fond of Sebastian the crab from The Little Mermaid. And I also have a soft spot for Ray the firefly in The Princess and the Frog.

RI: Do you ever reach a point where you can’t watch one of your films again?

JM: I usually don’t go out of my way to see our films after they are released. We see them so many times during production that we see them in our sleep. I still see the mistakes and things I would have liked to change or now see as improvable and it can make a neurotic person like me even a little more cuckoo if that’s possible.

RI: You said “We see them in our sleep”. That must make for some pretty impressive dreams!

JM: And occasional cold sweats.

RI: After a lifetime of animation, are you able to walk into a room WITHOUT identifying which object would be the best to suddenly spring to life and start singing?

JM: We try not to be too overwhelmed by the props around us but I do carry a sketchbook around at times and even people sometimes unbeknownst to them find their way into these films. And oh yeah, that coffee maker over there…!

With special extra thanks and love to Caroline & Lauriane for their great help!