In 1995, a small animation studio named Pixar released a movie that revolutionized the world of animated films. With genre-defining technology, gorgeous colors and animation, irresistible characters and a healthy dose of wry humor, audiences everywhere fell in love with Toy Story.

A beloved sequel and more than a half-dozen blockbusters later, Pixar’s next leap forward takes viewers back to the story that started it all. Woody, Buzz, Jessie, Mr. and Mrs Potato Head, Slinky Dog and Hamm – alongside a surprising cast of new toys – returns to the big screen in Toy Story 3, the third installment in Pixar’s classic series.

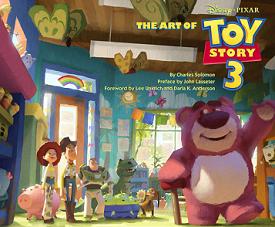

In The Art of Toy Story 3, internationally renowned animation historian Charles Solomon explores the technical challenges, triumphs and emotional hurdles that faced the Pixar team as they developed the toys’ new adventure. With more than 250 pieces of Toy Story 3 concept art, this deluxe volume provides a memorable narrative of the entire Toy Story trilogy.

Author Charles Solomon [below, by Pres Romanillos] shared with us his journey through the writing of this new, exciting book!

Animated Views: How did come to write this book, The Art of Toy Story 3?

Charles Solomon: Emily Haynes at Chronicle Books and Leigh Anna MacFadden at Pixar approached me about writing the book. Although I was completing a book about Disney’s Beauty and the Beast and teaching a class at UCLA at the time, it was much too interesting a project to turn down.

AV: How was it decided to include that wonderful, big introduction on the development of the first two movies?

CS: When I first discussed the idea of the book with Emily and Leigh Anna, I suggested that we include more text than the standard “Art of” book, and they agreed. We all felt that it was important to place the new film in the context of the earlier Toy Story features.

AV: How did you work on that part?

CS: As I often say, the line between historian and packrat is a fine one. I still have the interviews I did with the artists about the first two films. And everyone at Pixar was very generous about sharing their memories of the earlier Toy Story films, as well as their thoughts on the new movie. I hope the Introduction helps readers understand the progress of the Pixar artists and the Toy Story films in ways that deepen their appreciation of the entire trilogy.

AV: You are a noted writer on Disney animation, especially for your books on Disney history and Disney traditional animation. Where does your interest for Pixar’s CG animation come?

CS: I did my first interview with John Lasseter in 1982, when he and Glen Keane were working on their test based on Where the Wild Things Are. I’ve been writing about CG for a long time. And Pixar consistently produces some of the best animated films in the world.

AV: Do you see any connections between Pixar’s present modus operandi and spirit, and the ones of the time of Walt Disney?

CS: The Pixar artists clearly learned a lot from Walt Disney and his films. When you visit the studio, you can sense the energy of artists who are excited about their work, who know what they’re doing is good and new — which is how the old animators described Disney under Walt, especially during the days of the Hyperion Studio.

AV: As an historian yourself, how do you see/consider the evolution of Pixar from its beginning to today?

CS: I see a lot of parallels between the evolution of Pixar and the evolution of the Walt Disney Studio. The artists at both studios spent years making short films, learning the strengths and weaknesses of their medium, developing their skills, learning how to tell stories effectively in a new technique. Those years of effort led to two landmark films in the history of animation: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Toy Story.

AV: For this book on Toy Story 3, what was your most memorable interview?

CS: I spoke to more than 40 people for the book, so it’s difficult to pick a favorite. I think the most touching was John Lasseter, when he told me about the parallels between Toy Story 3 and his own experiences taking his son to college. It was also very moving to hear the various artists talk about Joe Ranft and how much they missed his contributions.

AV: May you tell me about your most interesting new encounters?

CS: Although I’d spoken with him before about other films, I did several interviews with Lee Unkrich. He’s very smart and interesting to talk to. One new friend I made during this project is Dice Tsutsumi — a charming and enormously talented artist. He patiently endures my attempts to speak Japanese.

AV: In this book there’s an extensive chapter on color script, which is rather unusual for these kinds of art books. How and why did you decide to stress this important yet often neglected aspect in the making of a film?

CS: One of the “perks” of my job is being able to call attention to the work of talented artists whom the public may have overlooked. The color script has become an important part of making an animated film — it offers an overview of the film that presents the emotional and visual elements simply and clearly. I hope the reader will gain an understanding of how important the color script is, an understanding that will enrich his viewing of the film. And the paintings Dice and his crew had prepared were simply drop-dead gorgeous: any author would be happy to have visuals of that caliber in his book.

AV: You interviewed Randy Newman, which is also unusual for an art book. As a specialist of animation yourself, how do you see the importance of music in an animated film?

CS: Animation and music have been linked since the silent era: Paul Hindemith wrote a score — now lost — for a Felix the Cat cartoon in the ’20s. During the ’30s and ’40s Walt Disney and his artists also showed how a well-written, well-placed song can relate important emotional elements and plot points in a very concise way. Howard Ashman reminded audiences and filmmakers how effective a song in animated movie can be during the ’80s. Although a lot of recent animated features have been clogged with unnecessary musical numbers, Randy Newman’s songs help the tell the story in all three Toy Story films.

Although my tastes run to classical music and opera, I’ve been a fan of Randy Newman since I first heard Simon Smith and his Dancing Bear. I’m only sorry we didn’t have more time to talk.

AV: In the end of your book, you quote Darla K. Anderson saying: “All the Toy Story movies have been about mortality.” Can you tell me about that?

CS: All the Toy Story films — like all great movies and indeed, all great story-telling — involve serious questions. Woody may be a toy cowboy, but he confronts the unhappy facts that he may cease to be needed or to exist, or that the person he loves most may stop loving him. Pinocchio risks his life to save Geppetto; Beast will sacrifice his own happiness for Belle because he loves her; Chihiro discovers her inner strengths through the trials she undergoes at Yubaba’s bath house in Spirited Away. If the audience doesn’t share the characters’ journey, what’s the point in telling the story?

AV: She also says: “You can keep peeling that onion and go as deep as you want into it.” How deep do you go into Toy Story 3?

CS: As Darla pointed out, the artists who made Toy Story have aged. Many of them have become parents and seen their children grow up. Artists whom I knew as skinny 20-somethings now have some gray hair; so do I. Their films reflect the changing perspective that age and its inevitable losses bring. If I had written a book about Toy Story in 1995, the tone and style and content would all be different from this one. If the same artists make a film 15 years from now, it will reflect subsequent changes in perspective, as would a book about it.

Growing up and older isn’t always fun, but it’s preferable to the alternatives.

With very special thanks to April Whitney at Chronicle Books!