The son of a music educator and a choral director, taught in violin, string bass, mandolin, ukulele and concertina, Pete Docter could have become a famous musician. But he happened to prefer doodling during concerts rather than listening to the music!

The son of a music educator and a choral director, taught in violin, string bass, mandolin, ukulele and concertina, Pete Docter could have become a famous musician. But he happened to prefer doodling during concerts rather than listening to the music!

Through drawing and arts, this reader of C.S. Lewis and L. Frank Baum could create on paper and in flipbooks, or in three dimensions with scrap material, the imaginary worlds that inhabited his dreams, especially the environments he discovered on family vacations at Disneyland. The Muppet Show was also an important part in the building of his artistic personality.

So, art won his heart, and more precisely animation, where he became not only an animator, but really a multifaceted artist, going from the story department to directing. After brilliant studies at Cal Arts (including kudos for the Student Academy Award winning short Next Door [see below]), he started his career in hand-drawn animation for Disney Feature Animation, Bob Rogers and Company, Bajus-Jones Film Corp, and Reelworks in Minneapolis.

Upon arrival at Pixar in May 1990, Pete created and directed animated commercials. He then was named supervising animator on Toy Story, wrote the initial story treatment for Toy Story 2 and helped storyboard A Bug’s Life before beginning work on Monsters, Inc. in 1996, which marked his debut as an animated feature film director. Pete was also the executive producer and contributed to the development of the story for the 2008 Pixar release, WALL-E.

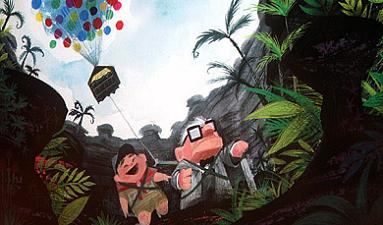

Now, with Up, he imagined a comedy-adventure about a 78-year-old balloon salesman who finally fulfills his lifelong dream of a great adventure when he ties thousands of balloons to his house and flies away to the wilds of South-America. But beyond the imagination, the poetry, the humor, the adventure and the technique (notably its being the first Disney/Pixar film produced in 3D), what makes Up (and all of Pete Docter’s films, by the way) so successful is its acknowledgment to its heritage.

A genius of his own, Pete Docter is at the same time a man of tremendous culture and respect for animation history under all its forms, and an animation historian. And that’s precisely what we talked about with him!

Animated Views: You’re known as a big Disney classic fan and, as we can see it in Up, there are some visual connections with Dumbo, and the idea of leaving the world behind flying in the sky in not far from Peter Pan among other references.

Animated Views: You’re known as a big Disney classic fan and, as we can see it in Up, there are some visual connections with Dumbo, and the idea of leaving the world behind flying in the sky in not far from Peter Pan among other references.

Can you tell me about your relationship to that heritage and how you infused it into your own film?

Pete Docter: I grew up at an age where we didn’t have videotapes or anything like that. So, I would just wait with great anticipation for every re-release of the features as well as the Walt Disney Presents broadcasts on television. When something would come on animated, I didn’t dare blink for fear I might miss something, because you were not going to see it again for who-knows how long. I used my tape recorder just to play back the sound because that was the only way to capture the program other than just try to remember it.

I loved those movies and still do. But, I think, the thing we were trying to get in this film that I noticed in a lot of my favorite Disney films was this balance of all these elements you have: this wonderful, fun, goofy stuff, that action-adventure sitting on the edge of your seat, and then you always have this emotion. And in the great films like Dumbo and Pinocchio, you have these scenes. That’s really as Joe Grant used to say, that’s really what you give the audience to take home, that’s what they think about after the film is over. And that’s what we were trying to do in this film as well.

AV: Up seems to be a beautiful blending of nostalgia and modernity, just like Walt Disney loved to do it.

PD: Yes, that’s really cool you noticed that. I think that, looking at the 1930s from our perspective has this really rich, nostalgic, warmth to it. Probably, for those who lived through it, they may not see it the same way that we do. But you look back at that time as a simpler time, a more innocent time and we tried to capture that in the film.

In fact, in the beginning of the film, for both their childhood and then what we called their married life, when they get married all the way through to Ellie’s passing away, we tried to present almost as though Carl is remembering this, that it’s replaying in his mind and it’s got this sort of rosiness to it and warmth because it’s infused with his emotions. And at the same time, working at a computer company, we’re always interested in pushing things technically and taking advantage in the latest innovations; there’s never a time when I work with the people here when I say: “Hey, maybe we could use that or that technique like you did in The Incredibles or in Cars or whatever” and they say: “Oh yeah, but we won’t do it again because it didn’t turn out good enough in those movies.” It looked pretty good to me but everybody’s always wanting to make things even better and better.

This is our tenth film, you know, and we’ve had this amazing opportunity to grow as artists just constantly trying to top what we’ve done in the past. So, it’s kind of this push-and-pull of looking back and have these warm feelings for a time gone by and yet really being inspired and interested in pushing forward at the same time. And, you’re right, Walt Disney certainly did that to great effect!

AV: The character of Carl demonstrates that oldness goes with wisdom. You work with the most innovative and state of the art animation studio of the time, and at the same time, you’re an animation historian yourself. Can you tell me about your interest in Disney history and how it nourishes your work?

PD: Well, even though it may seem new, I don’t think there is anything in the world that’s not based on wisdom and experience of things in the past. When Toy Story went out, a lot of people thought: “Wow, this is something really new and different. We’ve never seen anything like this. Pixar is a success”, etc. Of course, the truth is we all grew up with these films. John Lasseter, frame by frame, went through all sorts of movies growing up and worked at Disney for years. So, it’s based on the incredible work done by the giants before us: Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl. All those guys really blessed the trail and discovered all the basic principles that we’re using today.

It took some vision to John to see the possibilities in computer animation as at the time it was limited to flying logos and special effects and things. For him, to be able to see: “hey, we could fuse these two art forms – computer animation and real character animation – a lot of the techniques developed by those people” definitely took some vision. We’re always looking back to the great work of those guys. I don’t think we’ve even managed to meet the level of the work that they did. They were just such amazing artists. At their peek, those guys could really just produce powerful performances and capture nuances of feeling that we’re still trying to do today.

AV: I remember your fantastic interview with Art Stevens published in Walt’s People. You were also close to Disney Legends such as Frank & Ollie, and Joe Grant, who helped you shape out your story before passing away. Can you tell me about your most memorable meeting with such immensely important Disney artists?

PD: I remember one dinner. This is largely thanks to Howard Green that I got to meet all these guys. One of the great joys of doing Toy Story and having that be a success was then having the opportunity to go meet and talk with Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and of course getting to know Joe Grant best. But I remember one dinner where there was Frank, Ollie and Joe Grant. And of course, Andreas was there – he was always present at those meetings because he’s such an incredible fan of their work as well as a historian.

We were talking about the state of animation at the time which seemed to be rather lackluster. There was not very much good stuff coming out and Ollie was sort of asking: “Doesn’t anybody have a good idea to make for a film?” I saw Joe sort of smiling and then he goes: “they all seem like good ideas…until you tell them to somebody else!” He was absolutely right. When said by yourself, these seem like genius things and then, when you have to pitch them to someone, they start to fall flat. The process is such that, at Pixar, we’re kind of following the same footsteps as Walt Disney. We have this whole process which allows us to constantly make the film better and better and really try to get to the essence of what inspired the idea to begin with in order to communicate it clearly, put it forward in the best possible light.

There’s a lot of times when you’d have a pretty good idea and you put it forward one time and it falls flat. And then, just by changing a couple of things, and emphasizing one thing, reducing some other details, now you put that same idea across and it communicates clearly and is much more entertaining and everybody loves it. So, a lot of times, it’s just the execution of how you put that across.

AV: In Up, there are also many references to flying machines like in Miyazaki’s films. Can you tell me about his influence on you?

PD: Miyazaki, I think, has the ability to capture real-life details, but of course caricatured. He’ll find sometimes just some nuances of behavior, you know – the way a child eats, or sometimes nature – the rustling of leaves through trees or the way water cascades over rock or something like that, just very subtle little things, but the audience recognizes them as truthful. There’s something about going to the theater, I think, in part what we want is a reflection of our own life. When animation does it very well, it’s almost like it belongs to another world, but you recognize something of your own in that other world. He’s able to just beautifully capture these little nuances, as well as, of course, just his really great storytelling. I don’t think anyone else does that as well as he does. It may be just a cultural thing, I don’t know, but he doesn’t seem as bound to sort of the strict story structure that we do or even Walt Disney. There is always a very traditional type of storytelling and I think Miyazaki kind of breaks from that in his attention to detail and his ability to capture these real-life moments. That’s what really sustains your attention to his films and makes them work so well.

AV: The writing of your story started from a drawing of an old man selling balloons. How was it to create a story both backwards – creating his backstory – and forward – creating his upcoming adventures – in other words, starting from the middle?

PD: In a way, that’s kind of what we’ve done on all the films. You land on these different ideas and concepts and things that really resonate and you go “yeah, I want to use that”, and then you have to kind of connect these ideas together, thinking backwards and forward to the story. There’s no real reason to this. Sometimes it works that you accidentally set something up.

For example, in Toy Story, when Buzz accidentally flies around the room, everybody’s getting all excited and Woody says: “That wasn’t flying. That was falling with style”. And it was just a funny line that we used for that scene for Woody to dismiss Buzz. And then, at the end of the film, when they run the rocket and then when Buzz starts flying with Woody, Woody says: “Buzz, you’re flying!”, and the original line was: “Well, technically it’s just gliding, but let’s not spoil the moment.” And after we were animating it, we were sitting in dailies and I said: “you know what this line should be? It should be ‘This isn’t flying. It’s falling with style'”, calling back to that earlier line. We actually went back, recorded it and changed the line. It was just one of those set ups that worked as a pay-off as well. Sometimes, it’s the opposite. Sometimes, you come up with the pay-off at the end and then you have to go backwards and kind of invisibly set it up.

So, it’s all as a kind of a process of going backwards and forward to the story. Of course, that’s an advantage that storytellers have, that the audience doesn’t. You’re experiencing it all in linear, straightforward time but we’re popping backwards and forwards throughout the story making sure that each thread works and that they connect. That’s just the way the process works.

AV: I remember that one of the difficulties on the writing of Mulan was treating such an abstract concept as “honor”. In Up, you treat love, oldness, death, nostalgia, and finding one’s place in society. Was it difficult to treat such unusual and abstract concepts in animation?

PD: It’s a good observation. Frank Oz is a great director and was an amazing performer of the Muppets. He was talking about that saying that the more specific you can get, the more generally and the more powerfully these ideas seem to communicate. If you speak very abstractly about them, they don’t land. But if you make some very specific character who has very specific problems, in the end, none of us are monsters or toys or old men who fly their houses off, but hopefully, there’s something in those specifics that we all see in our own lives, that applies more generally. The dichotomy of it is that the more specific you can get, the more powerfully the ideas communicate.

AV: Let’s go a little lighter now and talk about humor in Up. I remember, in the Snipe Trap “Upisode”, it was about several attempts at making one trap – variations on one subject – just like in the Roadrunner cartoons. Can you tell me about that aspect of your movie?

PD: Of course, the Upisodes were created to get interest to going in the film and for the internet stuff. But I think that, in the film generally, it is Warner Bros, too. We really tried to rely on character humor to drive the story. We do have a couple of gags, just jokes that are just slapstick, but most of the humor, of the laughs I’m most proud of are jokes that come out of character. In other words, they’re only funny because this guy says it. Knowing Russel. When he says: “you were talking to a rock”. It’s not necessarily a funny line, but just the way he says it, and who this character is gets a laugh from the audience. I think that’s something that the Warner Bros. guys had and certainly the Disney guys.

I remember actually writing to Ollie Johnston about Bugs Bunny and friends and he said something like: “Well, they’re great characters and fun to watch, but they don’t have the depth that films we worked on did, and I would really miss thinking about these characters as people”. I’m not sure I totally agree with him. I know where he was coming from and I think there are certainly a lot of sides to the Disney characters that Warner Bros. never really explored, you know, real depth and emotion. But those characters were really great and specific and to the point that you got a sense for how they would react. You really feel like you get to know these guys, Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam and all of them. So, there is definitely an influence from both studios on our work. I think the Warner Bros. cartoons are more kind of scrappy and rough. They don’t have the polish and finish that the Disney films do, but they’re oftentimes just funnier, you know, in their timing, in their gags. They’re able to kind of go more extreme. That’s just my opinion, of course.

AV: There are also some references to Disneyland, like the Explorer’s Club, or the Nickel Tour in your film. Would you like, like John Lasseter, to be involved in Imagineering, too?

PD: If I had to go back in my own life and look at what got me in animation, I think two strong influences would probably be The Muppets and Disneyland. Disneyland: you know in one part of your brain that this is all fake, it’s all artificial. You’re sitting in a trench cut through a field of oranges in Anaheim and at the same time, you’re utterly able to believe that this is a small town in the Caribbean being sacked by pirates. They would take you to these other worlds. It was so fantastic and I loved that! Your job at Disneyland basically is to play, to pretend. It’s like an extension of being a kid. There is something really cool about that and just the being able to take you to all these places makes Disneyland a little bit like a time machine in the sense that you’re going backwards and forward through time, through different places, which you’d never be able to do in real life. For me, it’s just such a fun experience and I’m just willing to just go there and suspend the disbelief.

There’s a great influence not only in that sense on our film, but also in the fact that it was 3D. It’s like a movie set. For the way we’ve been using the computer to make our films, it’s very much a similar process where we’re creating a three-dimensional set with lighting, with camera angles and props and all this. We use a lot of things that we’ve learned just by watching The Haunted Mansion, or the Indiana Jones ride, those types of things, choices that the Imagineers have made, cheats that they have done for the benefit of the audience, things that works only really from one angle. I remember seeing Pirates of the Caribbean once I got to go through it with work lights on and you see all over the place painted light, light that doesn’t actually exist. It’s just painted on the set. From the boat, as you’re cruising through, you’d never notice that. It’s completely artificial, and that’s beautiful. There’s something really cool about that! I’d love to be more involved with those parks and I hope that this film will have some sort of connection, some ride at Disneyland. That would be awesome!

AV: Carl’s dream is one of adventure shared with Ellie. What’s yours?

PD: Boy! I guess, in a sense, I’ve got my dream which is getting to work on these fantastic movies and just make stuff. I grew up making things for fun, not getting paid for it obviously. As a kid, I was always making either puppet shows or movies of my own or with friends of mine, cartoons, comic strips… I just enjoy the process of making, of creating something. The fact that I get to do that everyday is pretty fantastic!

With our sincerest gratitude and admiration to Pete Docter and special thanks to Hilary Goss.