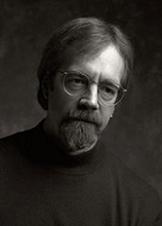

He’s the composer of Oliver & Company (and many other films including The Trip to Bountiful, Newsies, The Mighty Ducks II and III, What the Deaf Man Heard and Mama Flora’s Family) but he’s also known as one of the greatest orchestrators (WALL-E, Leatherheads, The Spiderwick Chronicles) and conductors (The Little Mermaid, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas) of our times.

He’s the composer of Oliver & Company (and many other films including The Trip to Bountiful, Newsies, The Mighty Ducks II and III, What the Deaf Man Heard and Mama Flora’s Family) but he’s also known as one of the greatest orchestrators (WALL-E, Leatherheads, The Spiderwick Chronicles) and conductors (The Little Mermaid, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas) of our times.

J.A.C. Redford distinguishes himself from other film music composers by an incredible versatility, feeling as comfortable in pop music or jazz as in concert music. Indeed, his concert works have been performed by Cantus, The Debussy Trio, Los Angeles Chamber Singers, Los Angeles Master Chorale, St. Martin’s Chamber Choir, Utah Chamber Artists and Utah Symphony. He has been featured in programs at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles and at London’s Royal Albert Hall. He has produced, arranged, and conducted music for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, and served as a consultant for the Sundance Film Institute, a teacher in the Artists-in-Schools program for the National Endowment for the Arts, a guest lecturer at USC and UCLA, and on the Music Branch Executive Committees for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

It is that rich experience that makes his music unique, drawing from an incredible array of influences. And Oliver & Company‘s score is no exception. From pop music (derived from the film’s catchy contemporary songs written and performed by the cast’s famous pop stars) to Mozartian influences (when Jenny plays the piano), his music is the New-Yorker melting-pot the film needed to make it a winner. Music, maestro!

Animated Views: Before we get into Oliver & Company, can you tell me about your musical background?

JAC Redford: I was born and raised in a family that was very artistic. My father is an actor and a director and a teacher of theater. He taught at the University of Utah for a number of years, and my mother is a singer, operatic soprano. I grew up listening to symphonic music and opera, musical theater. So, music came to me naturally, and particularly dramatic music, because of that background. I actually took my first theory classes in High School. At that time, I was playing the trombone. I was playing jazz primarily. I wrote my first pieces when I was 16, and I’ve been writing ever since.

I went to College for a couple of years and I dropped out. It really didn’t fit for me, and after that time, I studied privately. So, I trained in conducting and counterpoint, took film scoring classes here in Los Angeles from film composers. That’s how I got my training. My first jobs were for television, and my first professional work in the mainstream television industry was for Starsky & Hutch. So, I’ve been writing for television and film since 1976. I started out doing educational films and documentaries in Utah and then, after a few years, I moved here to Los Angeles, and I’ve been concurrently writing music for the concert hall, for chamber ensembles, choral ensembles, and the theater.

AV: These two dimensions of your work remind me of the work of one of your mentors, Thomas Pasiatieri.

JAC: He’s both a mentor, a friend and a collaborator of mine! He actually orchestrated Oliver & Company. He also orchestrated The Little Mermaid and I conducted it. But at the same time, he’s been nominated a number of times for his concert music compositions. So, we have a unique relationship where I was studying with him and hiring him at the same time!

AV: Oliver & Company is the first theatrical movie you scored for Disney. How did that happen?

AV: Oliver & Company is the first theatrical movie you scored for Disney. How did that happen?

JACR: Primarily, it happened because of my relationship with one of the Disney executives, Chris Montan. Chris and I wrote songs together and worked together on a television series called St. Elsewhere. We had become friends and enjoyed good working relationship. When the time came to do Oliver & Company, he brought me in. Of course, the songs were all written by a disparate group of songwriters and one of the things he thought that I could do and would be valuable for the picture to accomplish was to somehow weave those six very different songs together and make a score out of it that would utilize the themes from all of the songs.

AV: Thinking of Oliver & Company, what memories come back to you mind?

JACR: Well, there are some wonderful things about it that I remember as highlights in my career and Oliver & Company is one of them. I think it has been been the largest orchestra I’ve ever used. We had 90 pieces at one point. I have orchestrated for large groups, especially for composer James Horner, but for me, to be up conducting in front of a group of 90 was truly a thrill! We needed that many, because there were some places in the score where there was a lot of noise and we needed to have the availability of all those instruments just to be able to compete with the sound effects and to have broadest possible palette for the expression of the emotional contours of the film.

So, it was a lot of fun to work on this film, and I was totally committed to the process of making it the best score that I could make. We all had the sense that it was a very special project. The film after that was Little Mermaid, so Oliver & Company became sort of the stepping stone to Disney’s great success through all of those pictures. And when Mermaid came along, they called Tom and myself to help Alan with the score because of the success of Oliver & Company and of the success of what had been done. So, it was very much a bellwether score for me and I think a bellwether film for Disney.

AV: Can you tell me about your working relationship with director George Scribner?

JACR: George is a great guy! He’s one of the funniest guys. He’s such a laugh! His sense of humor is wonderful. He’s got good ideas, he’s very creative and interesting. We had a good relationship. I’d love to work with more people like George and with George some more!

AV: Your score really brings something to the story and to the emotion, not just like a mere illustration of what’s on screen.

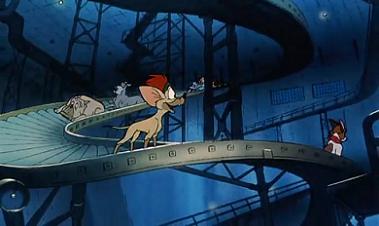

JACR: There may have been times when the music was played a little low underneath some of the action sequences, but there are cues like Bedtime Stories where they really let the music sing. And it was supposed to sing. There were moments when they really needed to provide a lift. If you just look at the visual images of that scene by themselves, they don’t necessarily contain within themselves all the expressiveness that needed to the there. So, we really have to get into the scene, in the flow of the scene, the dramatic arch of the scene. I sat down and I broke down the scene into its parts and looked at it and tried to recreate a built from beginning to end that would musically tell the story and the emotions that were going on there. It was very important to provide the characters with a sense of boundedness so that you came away from that with the feeling that these characters really cared about each other. So, I tried to invest the music with that sense of emotion. It just soared, it had to.

AV: That dramatic arc is also enhanced by smart choices in how and where to use the themes.

JACR: The choice of where to use the themes in the score was mine. That one of the things I look for in my own scores. When I create a theme, I like to use that theme as an extended metaphor, so that wherever it appears, it has some particular meaning and its underscoring is supporting some aspect of the character or of the story. So, I choose the place where I use the themes very carefully. As I said, there were a number of songs in that picture and I had to draw on those song themes and, when they played in the score, sometimes but not always, the intent was that the words would be remembered as the theme plays under that scene, so that there will be a little hint of whatever that song was trying to convey.

So, you do hear Oliver’s theme and it underscores his desire to belong to the group, because that theme is originally introduced when he is by himself and lonely in the big city at the beginning of the picture. So, when you hear that theme throughout the picture, it’s always touching how that sense of belonging is being fulfilled in pieces, and finally fulfilled completely at the end.

AV: Oliver is also associated with the Good Company theme.

JACR: Yes. I also used used that one. If Oliver’s theme is specifically connected to his loneliness and how it’s being fulfilled, it’s Jenny who is the instrument of that fulfillment ultimately. She’s the primary relationship that brings him to the new place in his life where he’s gonna be able to grow. It was kind of a test case in a way. They presented me with that song and they needed an arrangement to animate to. They just had some storyboard stuff as I recall. So, they gave me the song and there was just the piano part. I took it and expanded it and turned it into a kind of a fantasia on that theme. That’s the very first piece that I wrote and that was received very, very positively by everybody over at Disney. They loved that arrangement, so we went forward on some other stuff.

AV: Hence the large use of the Leitmotive technique, as you did on Oliver & Company, which truly benefits the film in making the songs and score feel as one whole.

JACR: I think it’s a technique that’s important as a cinematic scoring device in general. It’s something that can really give a sense of unity and meaning. It’s what I was talking about earlier: when a particular theme returns again and again, and returns in the right place, it can become a storytelling device. You’re following the development of a character and each time the theme comes back in, if it’s developed or in variation, even if it’s subliminal, you just emotionally become connected with the movement of that character. It builds just like it builds in Wagner’s operas or any other place where Leitmotives are used.

It has a tendency to create a sense of unity, a thread that goes throughout the entire story. It’s not the right technique to use for every picture, but it’s a very important one. It was one that was used by the first generation of film composers in abundance. In some respect, I think that’s the reason why it was less used at some time, because people perceived that technique as being old-fashioned. But it’s almost like saying that sentences and paragraphs are old-fashioned. Because it’s so fundamental to the process of scoring with intelligent design behind it. So, I don’t think it’s limited to animation. I think it’s true of all kinds of pictures.

AV: The overall score of Oliver & Company is a combination of many different styles, just like New York is a melting-pot of so many different influences. How did you manage that aspect of the score?

JACR: That’s interesting. I myself am very eclectic in my listening habits and in my writing and you can find elements of classical music, musical theater, pop music and even salsa in my score for the film just like in New York. You know, my father, as a director, every year, would direct a musical theater piece at the University of Utah in the summers and I went to them every year from the time I was six years old. So, musical theater is my blood. I’ve written a few musicals myself. So, that was in there, swimming around. The pop element just seemed like there needed to be something in the score that was reflective of the pop character of the songs, and they would make the songs feel like they were living in a consistent world.

You know, that was one of the difficulties: the songs were all written by different composers. It was only with Mermaid, the next project that came along, that one songwriter wrote all of the songs. The songs of Oliver & Company had very different styles. So, my job was to create a world in which all of the songs felt at home, like they all belonged to the same tapestry. I think that’s why the score has as much eclecticism in it. But it’s also part of my personality. I just really enjoy that! I had a lot of fun doing all the different styles and techniques. There were a lot of different kinds of sessions: big orchestral sessions, small overdub sessions, background vocals, horns players, rhythm section…it was wild!

AV: Oliver & Company is a very contemporary score, and you were one of the first composers to integrate electronic sounds into orchestral film music, like you did in the Bedtime Stories cue. How’s that?

JACR: I’ve been working with electronics really regularly ever since they first came on the scene because everybody in town here in Los Angeles in the TV business was using them, and a variety of different kinds of electronics, starting very primitively with electric pianos and electric guitars and various effects that could be achieved there, and then, as soon as synthesizers came in, I remember, when the Yamaha DX7 came is, that was one of the first synthesizers that could do a lot of different things, so, we just integrated that. Anytime any new piece of gear came along, it was integrated really quickly, and of course, the companies that produced those keyboards had interest in getting people involved in using them. So, the way that I wanted to use it was not in the foundation but as another choir of the orchestra.

Just as the orchestra has a woodwind choir, a percussion choir, percussion choir, string choir, brass choir, I also wanted to include an electronic choir so that you could utilize the sound as part of orchestra. I didn’t want to use the orchestra as a sweetener to the electronics, I wanted to integrate the electronics into the orchestra as part of the orchestra. So, that was the conceptual framework that I worked with. So, I used it in a way that I would use any other instrument. When I was orchestrating, I thought of it as what kind of colors would it bring into the sound, how can I reinforce or double other things for a particular color. Not to add weight necessarily. The MediaVentures sound (created by composer Hans Zimmer during the 90s) is essentially created of electronics over which an orchestra is laid, so that you get both worlds but it’s a like a combination of two worlds rather than bringing the electronics in as another aspect of the orchestra. So, I used it orchestrally, essentially.

AV: Now that Oliver & Company is celebrating its first 20 years, how do you feel about that particular score?

JACR: I’m really proud to have worked on it. I was really grateful to Disney for trusting me with a picture like that, and I still feel that way. Since then, I’ve worked on more than half a dozen different pictures for Disney and we’ve had a very good relationship over the years. That was kind of the starting point of those pictures. So, that was a particularly good thing for me in my career. I think every composer ought to have the challenge of writing a score that requires so many different approaches and the detail that had to go into writing for those chase sequences and so forth. It was really a challence from that standpoint. So, I was very happy to have that challenge.

AV: Thank you for Oliver & Company‘s beautiful music and sharing those memories with us.

JACR: I’d just like to say how grateful I am personally for your interest in this area of the art. I think the loss of passion in the art of a part of audiences has been a deep distress to me. But I am grateful that people are really treating film music with some seriousness and finding that it’s providing some kind of nourishment to them soulfully. That’s something I’m just thrilled by. It’s not like this music is just being written and then forgotten. When we composers get finished with the job, the parts go stored in a giant archive. It’s kind of like the end of Indiana Jones, when they take the Ark and put it in that huge warehouse. You’re pouring yourself into these projects only to see them disappear. But you guys, who listen to these things and enjoy them, are the ones who kind of keep the flame burning and keep the interest alive. That’s very satisfying to me. I really enjoy all my relationships and conversations like this one, where people actually care about the art. I just wanted to say “thanks”, I guess!

With all our appreciation to JAC Redford.