“In many ways, the work of a journalist is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a journalist truly does his job, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talents, new creations. The new needs friends.”

“In many ways, the work of a journalist is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a journalist truly does his job, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talents, new creations. The new needs friends.”

Last time, I experienced something new, an extraordinary film about a singularly unexpected hero. To say that both the movie and its maker have challenged my preconceptions about fine filmmaking is a gross understatement. They have rocked me to my core…

In the past, revered critic Anton Ego made no secret of his disdain for Chef Gusteau’s famous motto, “Anyone can cook”. But, after experiencing “something new”, he finally truly understood what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere. It is difficult to imagine a more unique background (like Czechoslovakia, where he was born, and England, where he grew up) than that of the genius who initiated the Academy Award-winning Ratatouille, who is, in this journalist’s opinion, nothing less than one of the greatest storytellers and animation artists. So, I went to Jan Pinkava, who happens to be that great artist, just before the Oscar ceremony for which he was co-nominated (for original screenplay), hungry for more.

And here’s the conversation we had…

Animated Views: First of all, you’ve got a PhD in Computer Science, you’re an animator, a story artist and a director! How do you deal with all these talents, all these skills?

Jan Pinkava: I was an animator first, then I studied Computer Science, then I did my PhD in Theoretical Robotics, then I returned to animation through Computer Graphics. I then started animating and directing commercials in London (at a company called Digital Pictures), then later at Pixar. I am blessed with a poor memory, so I can deal with skills by forgetting them. I can no longer do anything sophisticated with computers and I haven’t seen a robot, other than my sons’ toys, for nearly twenty years.

Jan Pinkava: I was an animator first, then I studied Computer Science, then I did my PhD in Theoretical Robotics, then I returned to animation through Computer Graphics. I then started animating and directing commercials in London (at a company called Digital Pictures), then later at Pixar. I am blessed with a poor memory, so I can deal with skills by forgetting them. I can no longer do anything sophisticated with computers and I haven’t seen a robot, other than my sons’ toys, for nearly twenty years.

But, like animation, there are other skills and interests that will never leave me. For instance, I have always been interested in figurative sculpture. Although I have done far less sculpting in recent months than I would like, I am sure that a keen interest in three dimensional figures and forms will be with me always.

AV: Is it the reason why you came to Pixar? How did that happen?

JP: When I was a computer science student I followed the development of Computer Graphics – the new, magical medium that was still just taking small steps toward making interesting pictures. I perverted all my computer science assignments to include some kind of graphics whenever possible. When I saw John Lasseter’s short Luxo Jr. I was inspired. I knew I wanted to work in that field.

After I left Digital Pictures, in London, I did some freelance commercial work for a while and then sent a showreel and resumé to Pixar. At that time it was quite unusual to send a resumé by email. The company was just beginning pre-production on Toy Story and needed directors to replace John Lasseter, Pete Docter and Andrew Stanton in the commercials group (known as the “shorts group”). I always hoped to make a short film in-between commercial assignments. It took a little while but eventually I got the chance.

AV: From your arrival at Pixar to Geri’s Game, can you tell me about the projects you worked on?

JP: In the “shorts” group we had two directors. Myself and Andrew Schmidt. The first project I directed was one of the last commercials in Pixar’s series advertising Listerine mouthwash. They were very popular at the time. I still think John’s earliest commercials in that series were the best and demonstrated a beautiful sense of storytelling even in a short form like a 30-second television commercial. My Listerine commercial, called “Arrows”, won a Gold Clio (the top award in advertising), the second such award for Pixar. I directed some commercials for clients like Levi’s, Coca Cola, Nabisco, some winning awards, but I always wanted to make a short film, and kept proposing little projects to Darla Anderson, our producer in the shorts group.

JP: In the “shorts” group we had two directors. Myself and Andrew Schmidt. The first project I directed was one of the last commercials in Pixar’s series advertising Listerine mouthwash. They were very popular at the time. I still think John’s earliest commercials in that series were the best and demonstrated a beautiful sense of storytelling even in a short form like a 30-second television commercial. My Listerine commercial, called “Arrows”, won a Gold Clio (the top award in advertising), the second such award for Pixar. I directed some commercials for clients like Levi’s, Coca Cola, Nabisco, some winning awards, but I always wanted to make a short film, and kept proposing little projects to Darla Anderson, our producer in the shorts group.

As Toy Story continued to grow, the commercial group in Pixar became less important and was on the verge of being shut down. I wanted to make a short and argued to keep the group going. During early production on Toy Story, most of the shorts group were drafted to help the movie. I chose to stay behind and “mind the shop” in shorts (I’m not so sure that was a such a great decision – I’m one of two people in the building at the time who did NOT work on the world’s first computer animated feature film). But that decision, to stick to my goal, led to my opportunity with Geri’s Game.

AV: Can you tell me about the origins of the Geri’s Game project?

JP: I believe there are good, entertaining stories in any subject, any character, if you look at the situation from an interesting perspective. The trick is to find that point of view. When I finally got the chance to make a short, I was told it had to be with a human character. I had drawers full of ideas for short films, but NONE with a human character. Nevertheless, I jumped at the chance. So I had to think up a story with a human character. I knew it would be technically hard for us to do, at the time, and I wanted to make the animation as good as possible. So I thought it would be a good idea to have as few humans as possible. So why not just one character? Then how can you tell a story with just one character?

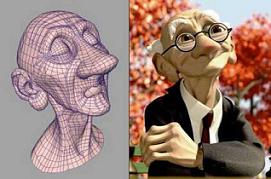

I liked Lasseter’s short Tin Toy, which was also very technically demanding at the time when John made it. Also with a human character. A baby. Actually because of that technical complexity the final film was not exactly what John had intended. Ironic, then, that it went on to win an Academy Award! The baby in Tin Toy was a little ugly, but worked well in the story, with good animation. As an animator I was excited to see the gestures and movements of a little baby so nicely done in CG. When it came to my short I thought, why not go to the other end of life and do an old man? From an animation point of view it’s fascinating to watch the slow and halting movements of a geriatric character. It was exciting to see that in animation in the computer. I also wanted the short to be all about the acting; close up; intimate; all about the expressions on the character’s face. So, how about a story with one old man? What can you do with that? That was the task I set myself.

I liked Lasseter’s short Tin Toy, which was also very technically demanding at the time when John made it. Also with a human character. A baby. Actually because of that technical complexity the final film was not exactly what John had intended. Ironic, then, that it went on to win an Academy Award! The baby in Tin Toy was a little ugly, but worked well in the story, with good animation. As an animator I was excited to see the gestures and movements of a little baby so nicely done in CG. When it came to my short I thought, why not go to the other end of life and do an old man? From an animation point of view it’s fascinating to watch the slow and halting movements of a geriatric character. It was exciting to see that in animation in the computer. I also wanted the short to be all about the acting; close up; intimate; all about the expressions on the character’s face. So, how about a story with one old man? What can you do with that? That was the task I set myself.

I came up with three story ideas. One about an old man playing with an elevator in his apartment building. Another about an old man feeding his sandwich to a cute but aggressive duck in the park. And lastly about an old man playing chess in the park against himself. Each story idea had some conflict, a building-up to a climax and a way to end it. I did boards for all three but it was the last one that interested me most. The idea came from my memories of my grandfather who was a keen chess player and was very very tenacious. He would even sometimes play against himself when there was nobody else to play with and his games could take hours.

When I pitched the idea of an exciting story about an old man who plays chess in the park against himself… well, let’s just say it was hard to sell. I learned a lot on the project and look back on it with pride and gratitude.

AV: Can you tell me about the artistic and technical challenges of the short?

JP: Ed Catmull wanted to do a short film to help Pixar’s ability to do human characters. This was an area where we were actually lagging behind the competition and John and Ed knew that in the long term the studio needed to be free to include humans in our stories once all the toys, bugs, fish, cars and everything else fantastical (and easier for computers) had been done.

JP: Ed Catmull wanted to do a short film to help Pixar’s ability to do human characters. This was an area where we were actually lagging behind the competition and John and Ed knew that in the long term the studio needed to be free to include humans in our stories once all the toys, bugs, fish, cars and everything else fantastical (and easier for computers) had been done.

Humans wear clothes. Clothes were very hard to do then. It needed research and development.

Humans have flexible skin and expressive faces. That needed new technology, too. For me, all that technology was just a means to making a little film. I wanted to make a funny, moving, believable story about a crazy old man, and to do it all with his acting. That was what excited me.

AV: How did you find the right balance between realism and animation (caricature, squash and stretch, etc) which is an important topic in Pixar’s aesthetics?

JP: The subject of stylization and caricature is very interesting. At the time of Geri’s Game there was a lot of talk in the media about realistic human characters as a goal for computer animation. People were beginning to try and make “synthespians”, or realistic characters to replace real humans in live-action movies, mostly for special effects and stunts. That eventually happened and it’s now something the audience takes for granted as a possibility.

I was more interested in what animation does best – caricature. I saw human characters in 3D computer animation as just stylized puppets. The same as stop-motion. But with the computer we could make the character move with greater complexity and make expressions much richer and more subtle than anything a physical puppet could do.

I was more interested in what animation does best – caricature. I saw human characters in 3D computer animation as just stylized puppets. The same as stop-motion. But with the computer we could make the character move with greater complexity and make expressions much richer and more subtle than anything a physical puppet could do.

I’m Czech. Although my parents left Czechoslovakia when I was only 6 years old, I was brought up in the UK surrounded by Czech books. My favorite children’s book illustrator was the great Jiří Trnka. He was a phenomenal artist. Sensitive. Thoughtful. Enormously prolific. There are very few Czechs, even to this day, who have not been deeply influenced by the work of Trnka in their early childhood. Trnka came from the deep puppet theatre tradition of Central Europe. His sense of form and style in depicting three-dimensional human characters – as puppets – was wonderful. Quite naturally and almost unintentionally my designs for Geri where hugely influenced by my exposure to Trnka. We all still have a great deal to learn from the classic puppet tradition.

AV: Can you tell me about the research and development you did on writing software for all these improvements, and how it helped the Pixar features that were to be produced?

JP: During the development of Geri’s Game, my education in Computer Science was very useful to me as a director. I could understand, at least conceptually, some of the technical details of the development work and could get a good sense of what was reasonable to ask of the technical team. I was able to know when we’d hit a wall and when it was worth pushing for more and better.

Most importantly, we had some great technical minds on the project. The technology that created the simulated cloth was developed by Michael Kass and took about a year to refine. He was one of the few people working in the field of cloth dynamics at the time. It was a difficult and twitchy process, with many setbacks and bizarre results. Sometimes Geri’s jacket was like concrete, sometimes jello or rubber, eventually more and more like… cloth and, after a lot of work and refinement, like the right kind of cloth. Today, cloth dynamic simulation as become a usable, reliable tool for creating CG characters.

The “flexible skin” technology was developed by Tony Derose, using a technique called “subdivision surfaces”. It is an evolution of a technique first pioneered by Ed Catmull many years before. It was so successful that the studio immediately began using it on A Bug’s Life which was in production at the time. It has been the basic method for the building of all Pixar’s digital puppets ever since.

AV: Now, on Ratatouille, can you tell me how the project was initiated?

JP: After Geri’s Game, I did animation work on A Bug’s Life, later some storyboarding on Monsters, Inc, and Toy Story 3. I still had many story ideas I wanted to realize. Mostly shorts. When I was asked by John Lasseter to create and develop a feature film at Pixar, I jumped at the chance. I still remember John saying “Jan, you have this great European sensibility”. It makes me laugh to think of it.

JP: After Geri’s Game, I did animation work on A Bug’s Life, later some storyboarding on Monsters, Inc, and Toy Story 3. I still had many story ideas I wanted to realize. Mostly shorts. When I was asked by John Lasseter to create and develop a feature film at Pixar, I jumped at the chance. I still remember John saying “Jan, you have this great European sensibility”. It makes me laugh to think of it.

I was given some time to write an outline for three ideas. On a trip to England, with my wife and new son, I set to work and was a immediately taken with just one idea. I wrote a long treatment of the story and pitched it on my return. For about a year I worked on it, with some help, but in the end it didn’t come together as I had hoped. The story world was great. But the story itself wasn’t right and that project was shelved (It’s a project I hope to come back to in the future).

I was asked to start again. I came up with three strong ideas.

AV: How did the pitch to John Lasseter go? Was he immediately enthusiastic?

JP: When I pitched the three stories to Pixar’s “brain trust” – John Lasseter, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, Joe Ranft and others – Ratatouille was the clear favorite. As soon as I said, “This is a story about a rat who wants to become a chef”, everyone burst out laughing. John loved the idea as much as I did.

AV: How did you come to the title “Ratatouille“?

JP: Ratatouille was always the title, from the very beginning. It seemed like an inescapable choice. It’s about a rat. It’s about food. It’s French. What other word has all those things in it and sounds so…melodic and silly? The idea of having ‘ratatouille’ be a key dish at the story’s climax seemed equally natural.

JP: Ratatouille was always the title, from the very beginning. It seemed like an inescapable choice. It’s about a rat. It’s about food. It’s French. What other word has all those things in it and sounds so…melodic and silly? The idea of having ‘ratatouille’ be a key dish at the story’s climax seemed equally natural.

Years later, the movie was being made, the plan for its promotion was being hatched and some people in the studio were worried that the word might be too strange (for an American audience), too foreign, too difficult to spell and pronounce. But a serious effort to find an alternative title couldn’t dislodge “Ratatouille“. For most of the audience it is strange and difficult. But the sound of the word captures the silliness of the idea perfectly. And if Pixar and Disney can’t teach the audience a new word, who can?

AV: What were the technical challenges on Ratatouille and how did you deal with them?

JP: Technically, the movie was a collection of some of the hardest challenges the studio had faced. There were many humans, complex clothing, lots of fur, water and food, to name a few; all incredibly hard to do well. It would take chapters to do justice to the technical achievements on this movie. It’s a great credit to Michael Fong’s hugely talented team that everything turned out so beautifully. Just building the digital puppets themselves was a herculean labor of love. Humans and clothing had been done before, of course. Since Geri’s Game, many advances had been made, but even for The Incredibles the cloth simulation had still been an enormous struggle. By the time we’d reached the end of preproduction on Ratatouille, cloth had been tamed as a truly usable tool. Fur was another one. In Monsters, Inc., there had been one really hairy character, Sulley. For Ratatouille we needed hundreds of rats. It took a big leap in the fur technology to make that possible and a whole new discipline of grooming and hair design. Just to get so much hair rendered by the computers, looking good and moving well was a great achievement. The many fire, water, smoke and steam effects that make the kitchen environment feel so real each required difficult innovations and technical developments.

Perhaps the greatest new challenge was in getting the food to look so good. Stylized, not real, but still appetizing. It all required a complex combination of modeling, physical simulation, artful painting, sophisticated translucency and textural effects with subtle lighting and cinematography all driven by a real understanding of what makes food look good on screen.

Something that isn’t often talked about is the work that was done on contact; things touching other things. I had wanted from the start to give the animators better tools for achieving the feeling of a tangible physical world where characters can squish up against each other and other things in the world. We wanted the audience to see and feel the physical connection between things more than ever before. This is hard to do in CG and was especially important for a cast full of squashy, flexible rats.

In the entirely synthetic medium of computer animation, those who create the technology that make the images we see on screen possible, and those who use that technology to craft the images so beautifully, are the unsung heroes of the movie world.

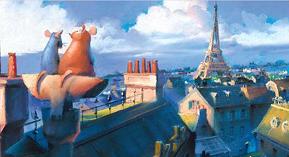

AV: On the artistic direction, how did you imagine your film? And how did you work on that with art director Harley Jessup?

JP: Among the greatest pleasures of making Ratatouille were my many conversations with Harley Jessup about the look and feel of the film. It felt as if we understood each other perfectly and Harley’s sensitive eye and prolific mind produced an enormous body of work – the visual stuff the movie is made of. Again, I was inspired by puppets and the scale-model feeling of stop-motion animation. There’s a great appeal in the small-scale hand made quality of things. If you look at, say, a full size frying pan and then at a small physical model of a frying pan, there’s a magical difference in the way you feel about those two things. We were both excited about bringing some more of that feeling to a CG movie. We wanted to give it more warmth.

JP: Among the greatest pleasures of making Ratatouille were my many conversations with Harley Jessup about the look and feel of the film. It felt as if we understood each other perfectly and Harley’s sensitive eye and prolific mind produced an enormous body of work – the visual stuff the movie is made of. Again, I was inspired by puppets and the scale-model feeling of stop-motion animation. There’s a great appeal in the small-scale hand made quality of things. If you look at, say, a full size frying pan and then at a small physical model of a frying pan, there’s a magical difference in the way you feel about those two things. We were both excited about bringing some more of that feeling to a CG movie. We wanted to give it more warmth.

Just the effect of making scale models of things seems to be very like the intuitive design process of caricaturization. It’s all about simplifying and exaggerating. When you’re making something small you have to leave some details out and make sure the important parts remain. It’s a bit like boiling down a sauce to get a more concentrated flavor. Add to that the accidental irregularities and coarser textures of materials when viewed close-up and something special happens.

Harley brought in some doll’s house furniture and props for the artists to study. He encouraged a technique of drawing very small and then blowing it up on the photocopier. He was excited about using over-large print patterns, for example, as if small things had been made out of full-scale cloth. We experimented with the scale of weave and stitching on the cook’s jackets and tweaked the folds and wrinkles in the cloth simulation to feel simple and small-scale. Imperfections and wobbliness were part of every set and prop that was made. That kind of work went into everything.

AV: Can you tell me about the original story you imagined?

JP: In very broad terms the outline of the story I conceived is close to the final movie. Of course, many people contributed so much to the development of the story and the characters over the years that it becomes impossible to tease apart one ingredient from another. It’s a collaborative process. One can point to many ideas and scenes that were there in one form or another from the beginning. For instance, Remy’s falling in the kitchen, fixing the soup and getting caught, his puppeteering Linguini to success, their falling out, Remy’s double life, the flashback to childhood (Gusteau’s in the original story) after tasting the ratatouille, the rat family’s heist in the food safe, Remy’s reveal and the cooks’ walkout, the kitchen full of cooking rats in the climax. This is all on the surface of the story. Where the movie differs most from the story I imagined is in its tone, in the story’s core idea and in Remy’s character. Perhaps this is, at least in part, a matter of… “European Sensibility”.

JP: In very broad terms the outline of the story I conceived is close to the final movie. Of course, many people contributed so much to the development of the story and the characters over the years that it becomes impossible to tease apart one ingredient from another. It’s a collaborative process. One can point to many ideas and scenes that were there in one form or another from the beginning. For instance, Remy’s falling in the kitchen, fixing the soup and getting caught, his puppeteering Linguini to success, their falling out, Remy’s double life, the flashback to childhood (Gusteau’s in the original story) after tasting the ratatouille, the rat family’s heist in the food safe, Remy’s reveal and the cooks’ walkout, the kitchen full of cooking rats in the climax. This is all on the surface of the story. Where the movie differs most from the story I imagined is in its tone, in the story’s core idea and in Remy’s character. Perhaps this is, at least in part, a matter of… “European Sensibility”.

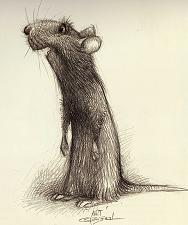

AV: There were characters in the rat herd, like Remy’s mother Désirée and others. Can you tell me about them and how you work with character designer Carter Goodrich on that?

JP: Remy had a father, Django, a mother, Désirée, hundreds of anonymous siblings, and a special brother Emile. The rat community was imagined as very loud and earthy, full of squabbling and in-fighting, and all the trappings of a live-for-now low-life culture. There was also music; a band. They lived by stealing and their favorite target was the trash cans of nearby restaurants. There was a small group of heist characters, of which only Git, the big lab rat, survived to the final version. Carter Goodrich did great things with these ideas. He was our principal character designer during development. I really liked the work he did for Pete Docter in the early days of Monsters, Inc. If some of those monsters could have been in the final movie it really would have been scary. I was very glad to have Carter working on Ratatouille. We’d give him descriptions of the characters. He’d come up with brilliant drawings. That was it. Sometimes he would do different versions based on the feedback. Sometimes, like in the case of Emile, his first batch of drawings had a perfect rendition of the character. These drawings would then form the basis of physical maquettes, sculpted by Greg Dykstra or Jerome Ranft.

JP: Remy had a father, Django, a mother, Désirée, hundreds of anonymous siblings, and a special brother Emile. The rat community was imagined as very loud and earthy, full of squabbling and in-fighting, and all the trappings of a live-for-now low-life culture. There was also music; a band. They lived by stealing and their favorite target was the trash cans of nearby restaurants. There was a small group of heist characters, of which only Git, the big lab rat, survived to the final version. Carter Goodrich did great things with these ideas. He was our principal character designer during development. I really liked the work he did for Pete Docter in the early days of Monsters, Inc. If some of those monsters could have been in the final movie it really would have been scary. I was very glad to have Carter working on Ratatouille. We’d give him descriptions of the characters. He’d come up with brilliant drawings. That was it. Sometimes he would do different versions based on the feedback. Sometimes, like in the case of Emile, his first batch of drawings had a perfect rendition of the character. These drawings would then form the basis of physical maquettes, sculpted by Greg Dykstra or Jerome Ranft.

AV: From the looks of Dominique Louis’ concepts, there seemed to be many other things that were to take place in the sewers. Can you tell me about those?

JP: The original story had more about Remy leading a double life; more torn between his new life in the kitchen and his life as a rat, at home with his family. Naturally, they lived in the sewers below the streets of Paris. There were intimate scenes with Remy’s parents and his brother Emile and also scenes where the entire rat ‘village’ would gather as in a village square. Most of the sewer environment designs were of this ‘piazza’ in the sewer, where several tunnels converge. We wanted the sewer environment to be somewhat miserable, for Remy, yet still visually appealing. A fun counterpoint to the drab surroundings was the rats’ use of found objects and junk to make their homes. Dominique’s great sense of atmosphere and astonishing command of light in his pastel drawings really brought these environments to life.

AV: Was it intentional from you to appeal to artists of European origins (just like you): Enrico Casarosa (Italy), Dominique Louis (France), etc. What did they bring to the film from that point of view?

JP: There’s that “European Sensibility” again! No, we didn’t go looking for Europeans. Pixar is full of people from all over the world, some from Europe. We were lucky to have talent like Dominique and Enrico on the production. Dominique created amazing pastel drawings visualizing the scenes first on paper, then later entirely digitally. I called him “maitre de la lumiere” for his facility with suggesting rich lighting. Dominique’s style was very emotional and theatrical and actually, in some ways, perhaps not so “European”. I’ll admit, I do have a soft spot for Italian artists. Enrico came to Pixar from Blue Sky in New York and was one of the first story guys on Ratatouille. He worked like a trooper. Like many from his background Enrico’s style is strongly influenced by Japanese artists and Miyazaki in particular. I love Enrico’s drawings. He’s a Genovese Genius. His early beat boards for the film were very influential in setting the tone.

JP: There’s that “European Sensibility” again! No, we didn’t go looking for Europeans. Pixar is full of people from all over the world, some from Europe. We were lucky to have talent like Dominique and Enrico on the production. Dominique created amazing pastel drawings visualizing the scenes first on paper, then later entirely digitally. I called him “maitre de la lumiere” for his facility with suggesting rich lighting. Dominique’s style was very emotional and theatrical and actually, in some ways, perhaps not so “European”. I’ll admit, I do have a soft spot for Italian artists. Enrico came to Pixar from Blue Sky in New York and was one of the first story guys on Ratatouille. He worked like a trooper. Like many from his background Enrico’s style is strongly influenced by Japanese artists and Miyazaki in particular. I love Enrico’s drawings. He’s a Genovese Genius. His early beat boards for the film were very influential in setting the tone.

I did want the film to have a genuinely felt Parisian flavor, but knowing that it would be made mostly by Americans in the USA. One of my favorite Disney films is One Hundred and One Dalmatians. It was the first thing I saw in the cinema in England after my family left Czechoslovakia. Growing up in England I later realized that the flavor of London that the Disney artists brought to the film was not really accurate, but rather it was an American perspective on London, informed by a genuine affection for the place and its people. That sympathy came across in the movie and gave their London an authentic quality all of its own. I hoped we could do something similar with Paris.

AV: Did you go to Paris for research? What are your memories of that trip?

JP: We went to Paris. More than once. With our guide, Roberto, we were able to see the kitchens of top restaurants like Guy Savoy, Taillevent, Lassere, La Tour d’Argent, to talk to the staff, interview the chefs, and of course we did have to eat. I’ll never forget one particular duck dinner. Sometimes the artist has to suffer! Outside the restaurants, we wanted to get a feeling for the city from a different perspective, at a scale appropriate for a rat. Our tours of the sewers, the catacombs, the Canal St. Martin were an eye-opener. There were many exciting discoveries; some that didn’t make it into the final movie, like the pre-dawn hours at Rungis market (the belly of Paris), and some that did, like the famous exterminator store in the Les Halles district complete with mummified rats hanging in the window. Some things you can’t make up.

JP: We went to Paris. More than once. With our guide, Roberto, we were able to see the kitchens of top restaurants like Guy Savoy, Taillevent, Lassere, La Tour d’Argent, to talk to the staff, interview the chefs, and of course we did have to eat. I’ll never forget one particular duck dinner. Sometimes the artist has to suffer! Outside the restaurants, we wanted to get a feeling for the city from a different perspective, at a scale appropriate for a rat. Our tours of the sewers, the catacombs, the Canal St. Martin were an eye-opener. There were many exciting discoveries; some that didn’t make it into the final movie, like the pre-dawn hours at Rungis market (the belly of Paris), and some that did, like the famous exterminator store in the Les Halles district complete with mummified rats hanging in the window. Some things you can’t make up.

AV: At first, Ratatouille was intended to be the first Pixar feature film to be released outside of the deal with Disney. Did that change anything in the tone of the film you imagined? Did you have more freedom in that regard or didn’t that change anything for you?

JP: Ratatouille was the first film beyond the Pixar/Disney co-production deal. This turned out to have quite an impact on the movie and how it was made. Initially, from Disney’s perspective, it was off the radar. Pixar was paying for the movie’s development 100%. There was no pitching to Disney or sharing the progress of story reels. The review process, which was thorough and continuous, was entirely within Pixar. Actually, in practice, this was not much different from the several movies that came before. At that time Disney was going through upheavals and troubles and Pixar’s star was rising higher and higher. The real weight of authority for Pixar’s movies was with John Lasseter, the “brain trust” and Pixar management, not Disney.

As the end of Pixar’s deal with Disney approached, two things happened. The press began to speculate more and more about how Pixar might do without Disney and how the next mysterious project was shaping up. Within Pixar the post-Disney project got more and more attention as an important factor in the negotiations with Disney. All this put even more pressure on Ratatouille than was usual for a Pixar movie. It all certainly had an effect.

AV: What will you keep from your experience on Ratatouille and from your experience at Pixar?

JP: Ratatouille was an enormous experience as my first feature film. I am very proud of much that is in it, and I am delighted for everyone who worked so hard that the finished movie has been such a success. I would have liked to complete it, but Brad Bird was able to take it on, make it his own and lead the team to a very successful finish. I learned a great deal more than I imagined and look forward to gaining the benefit of that experience on my next project.

I came to the US to work at Pixar in 1993. It has been my pleasure and privilege to work with many extraordinary people in my 13 years with the studio. I am proud to have been part of the studio’s development and rise over the years. It’s been a marvelous time for which I will always be grateful.

AV: Can you tell me about your present projects?

JP: I’m working on a beautiful story for an animated feature film. It’s an idea that goes back to an experience in my childhood which is both personal and, I think, universal. Everyone can relate to it. It’s part of everyone’s inner life. There’s one very unusual character in the story. I haven’t seen anything like it on the screen before.

Our special appreciation and gratitude to Jan Pinkava for the time he took to kindly answer our questions.

Images ©Disney/Pixar