“It was late one fall in Halloweenland,

“It was late one fall in Halloweenland,

and the air had quite a chill.

Against the moon a skeleton sat,

alone upon a hill.

He was tall and thin with a bat bow tie;

Jack Skellington was his name.

He was tired and bored in Halloweenland.”

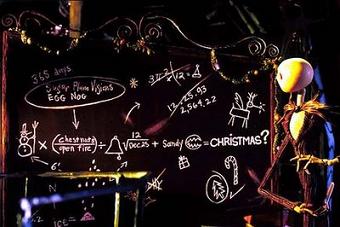

With just a few lines, young Disney animator Tim Burton created a phenomenon. That was in the early 80s. Of course, like many masterpieces, it took some time, even some years for his nightmare to become a reality, but nobody could have foreseen that 1993’s first ever full-length stop-motion feature film would generate even more than a craze: a culture of its own. From by-products to accessories, it even transmogrified one of the most revered Disneyland attractions into a brand-new theme park experience, The Haunted Mansion Holiday, that became a classic at Disney’s Magic Kingdoms.

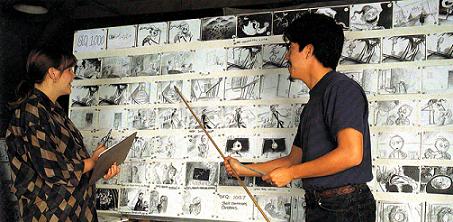

But today, with the release of the Ultimate Collector’s Edition of the movie, it’s time to go back to the essentials, to the origins of the myth. That’s why we turned to Mike Cachuela [right, below], who was one of the storyboard artists of the film, to remember in his company the beginnings of the production: about how such a rich and wide universe was born, in a small, old and disused studio of the San Francisco Bay area, and an artist’s impressive career went from Skellington Productions to Pixar Animation Studios…

Animated Views: We’re talking today about your role storyboarding on The Nightmare Before Christmas. How did you start in the business and land that position?

Mike Cachuela: I’ve always liked to draw when I was growing up and then, I was really inspired by the Star Wars films, basically. There’s this guy, Joe Johnston, who did much of the conceptual work in those films, like the vehicles, costumes and stuff. I wanted to be him, like millions of other kids, and do that kind of design work. Earlier than the Star Wars movies, seeing the prehistoric depictions in Fantasia was a great influence on me. The images of the earth forming in such dramatic, violent but beautiful scenes captivated me. It amazed me that the filmmakers could transport you to such a strange world. A time and place that no one had actually seen, but here Disney artists had done their best to convey it in such an emotional way. Eventually, I wanted to go to USC or UCLA and major in live-action film, but along the way, I met some Disney animators who saw some of my drawings and said: “Hey, you should check out an art school called California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California!” And so I did, and I loved it because it was just a great school, with a lot of different mediums and disciplines and a great animation department. I could take my drawings and my desire to make films and have them both there, at the Cal Arts animation department.

AV: How did you learn telling story via illustration?

MC: The artist I mentioned, Joe Johnston, did storyboards for some of the Star Wars films, although they were more technical. His renderings started my interest in storyboard drawings. One of my earliest explorations in storyboarding was in high school in the back of a classroom, with a friend of mine, Robert Gibbs, who is now also a storyboard artist at Pixar, interestingly enough. We would sit in the back of the class and try and make each other crack up. While the teacher was speaking we couldn’t talk, though we could both draw. So, we could try and draw funny stories and show them to each other since our desks were next to each other. It was the best school: telling a story visually and not being able to communicate any other way, and communicate quickly. Cal Arts was a good place to learn as well because you’re starting to make you own films. So, the first thing you do is storyboard out your story. If you value that process, you’ll show it to your classmates, get their reactions and make adjustments. And I think that people who did that had better films.

AV: Who were your mentors back then?

MC: I was fortunate enough to have a teacher in Cal Arts named Joe Ranft, who was one of the modern storyboarding gurus. It was his brainstorm to have a head of story position on Disney projects while he was at Disney, to work in liaison between storyboard artists and the director and the producers. He obviously had tons of wisdom to pass on about storyboarding. One of the exercises he did, our first day in his storyboarding class, terrified a lot of people, because many animators are kind of shy. He said: “I want you guys to think of a story and you’re going to tell it to us. Try to keep it about ten minutes.” So, we were going to, one at a time, stand up in front the class and tell a story. Immediately, you’re thinking: what story is gonna be entertaining? How to hold the attention of your classmates, your audience? What will draw you in and make you want to follow the story? What’s going to be poignant and stick in your mind? It was a very eye-opening exercise. It was a test in basic story mechanics, making an entertaining chain of events and having that affect the audience, hopefully, in a good way.

AV: What makes a good storyboard?

AV: What makes a good storyboard?

MC: On a drawing level, it’s the ability to direct your eye in a composition. We’re talking about a single panel. And that’s using tones, lights and darks, and just composition. But more importantly, whenever you can, knowing and staging the emotional beats of a scene. You need to be able to give a clear representation of your character’s journey through a scene and telling what affects them in the world you’re creating, you’re asked to put them in and how they react to it. In that way, you’re kind of a director.

AV: And then you very quickly got to work on first-rank productions like Nightmare Before Christmas.

MC: That was actually through Joe Ranft. At Cal Arts, my classmates and I were talking about what would be the coolest thing to come about after school and several of us were like: wouldn’t that be great if Tim Burton did a stop-motion feature? He had done this great stop-motion short called Vincent. So, shortly after school, I learned that was indeed happening in San Francisco, and I was working in L.A. at the time on my first animation job. There was a very talented director, Henry Selick, who was directing it and Joe Ranft was the head of story on this particular project. I had wanted to get out of Los Angeles because I wasn’t a big fan of the city, of what was going on in that city animation wise. Also, I’d been talking to Pixar off and on, who were located in the Bay Area near San Francisco. I called Joe and he said: “as a matter of fact, we’re looking for storyboard artists on Nightmare Before Christmas.” So, my original plan was to work on Nightmare a little while and then go on to Pixar because they had told me that they were starting their first feature film and were going to need artists for that. So, I started at Skellington as a kind of a part-time job, but because I loved the studio so much, I ended up working there probably the longest on any single feature, about a year and a half! And it was great!

AV: How were your working conditions there?

MC: It was originally a television studio in San Francisco that was scheduled for demolition a couple of years down the line. Henry Selick very much likes to instill a creative atmosphere in the work place. Because of that and the scheduled demolition, there wasn’t the urgency to keep the building in pristine shape. So, there was a bunch of those crazy film-production artists who went wild decorating it, there was graffiti everywhere and sculptures using, like, motorcycle chassis and stuff everywhere you looked. It was a very creative environment to work in, and I think that helped the tone of the film.

AV: What was the process of working on that project?

MC: The way Joe Ranft liked to work was: he would cast a storyboard artist on a scene, be it a comedy or action or whatever and you would take a couple passes at it. If you get tired of the scene – because eventually, after working and re-working it, going back and forth with editorial and the director, you would get a little sick of it – Joe would hand it off to a different storyboard artist. So, there were different scenes that several storyboard artists worked on at different times. The ones I think am the most proud of is are the Lock, Shock and Barrel sequence I worked on with Jorgen Klubien, who’s another Disney storyboard artist/animator, the Jack delivering Christmas presents sequence and the Oogie Boogie battle at the end, which was a sequence I worked on for a long time. I was also doing some 2-D animation of shadows and ghosts at the time, so I was kind of jumping back and forth.

The work depended on the sequence. When we had to work on the Danny Elfman songs, that we basically had as guides, we would just illustrate what was happening with the lyrics. Usually, at the beginning you would have your own sequence, you know. Sometime, you would pair up with another story artist in a brainstorming process. I would pitch my sequences to Henry, of course, and when he wasn’t available, I would pitch them to Joe Ranft or Jorgen Klubien and get feedback about what was working or what wasn’t working, and make adjustments. It was very collaborative. We worked in this kind of an atrium where there were no walls. We just had a few stands to put our boards on. So, you could always see what the other story artists were doing and compare notes. Also, on the other side of the walls from us was the Art Department, so you would go back and forth to see what was done with the environments. You could have conversations with the Production Designers or the Art Directors and do more brainstorming on how the environments would affect the action of the scene and the drama. All the departments were working together and Henry really encouraged that as well. He had a very strong vision about a lot of things, but he would really encourage people to go and talk to each other about different locations, and brainstorm.

AV: At some point, the only material you got was Danny Elfman’s lyrics for his songs. How did you deal with that?

MC: There were the lyrics of his songs and a very rough first draft of the script done that just kind of stitched them together with a loose story. Which actually didn’t help too much. So, there really was a lot of writing and re-writing on the boards between the songs, in order to come up with the best transitions.

AV: So, your work must have been much more creative than the traditional work of the storyboarders since you really had to fill the blanks and create a linear story. Do you remember any specific scene you created with that purpose?

MC: Let’s see. Some of the transitions I did were some cutting back and forth from the Halloweeners making their presents to the Elves making their presents at the North Pole. I did a lot of transitions like when the Halloweeners are closing a box and then it’s opened by an Elf. Those transitions cutting back and forth in that area. Also, I think something that I’m particularly proud of is when Sally jumps out the window. She hits the ground and falls apart, and sews herself back together. That was kind of tough because visually, it made executives nervous seeing a woman stitching her legs back-on which could make an audience squeamish. Henry came up with the idea to have Sally be a rag doll stuffed with leaves rather than have bloody stumps, which really helped. It was my duty to take that scene and convey the idea of Sally pulling herself together without making it too grotesque. Also, I did the gag of the Halloween snake – this is after Jack delivers the presents – swallowing the Christmas Tree. That was an idea of mine!

AV: Did you come to meet Tim Burton during that process?

MC: Well, not really. Tim Burton was off doing his other projects. He would visit the studio maybe three or four times over the course of the production. So, we rarely saw him. Although his drawings, his original ideas, were very influential and many of our designs were pretty much taken straight from his early drawings. He had his own strong opinions about where the story would go at certain points, and there were actually some battles at the end of the film when Tim Burton stormed out of the editing room and kicked a hole in the wall with his steel-toe boots! He was so angry! I suggested that Henry cut that section out of the wall out and frame it! Which he did!!

AV: Why was he so angry?

MC: Because Henry and I had boarded a kind of an alternate ending. It was something that Tim Burton just did not want. He wanted to stick with the ending he had envisioned.

AV: So, how was that ending of yours like?

MC: Well, you would see Jack and Santa over the years keeping in touch. And also, there was a sub-plot of Dr. Finkelstein who was the one who was behind Oogie-Boogie. It was amazing that it was that finally happier ending that really made Tim Burton going kick and hole the wall! But it was his prerogative!

AV: After Nightmare, it seems that you kept much in touch with Henry Selick.

MC: Yes. I’ve worked on all of Henry’s feature films. We became friends on Nightmare. Of course, there were times when our friendship was strained because I have my own personal vision and sometimes it didn’t quite connect with his. But for the most part, we work well together!

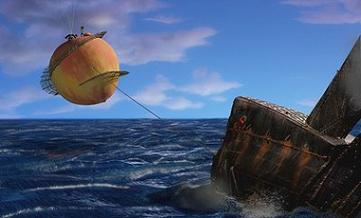

AV: So, what are your memories of James and the Giant Peach?

MC: I was initially one of the heads of story, with Kelly Asbury. We were responsible for setting up the storyboard department, finding additional storyboard artists, taking a first pass at boarding up the film while the script was being written. There was a hiatus in James and I went to work in Paris actually for a little bit, at Disney’s Studio there in Montreuil. When I came back, I did some more and more storyboarding. I storyboarded the shark attack and the pirate sequence and did some more 2-D shadow animation.

AV: Was it your idea to use Jack as a cameo in that pirate sequence?

MC: MC: No, I think it was Henry’s idea.

AV: On what film did you work in Paris?

MC: I started storyboarding on a short film called Runaway Brain, a Mickey Mouse short. And then, when it was over, I attempted to animate in the project. I was completely intimidated by these very talented young French animators who could draw amazingly well. I just couldn’t draw Mickey Mouse. He’s a very tough one to draw. He’s deceptively simple so, that didn’t work out! It felt strange being in Paris, in such an historical city and working on a Mickey Mouse short, I have to say!

AV: And then, another Henry Selick project was The Life Aquatic, the Wes Anderson movie. What was exactly your role on that film?

AV: And then, another Henry Selick project was The Life Aquatic, the Wes Anderson movie. What was exactly your role on that film?

MC: On Life Aquatic, Henry was heading up the stop-motion division of that film. Wes Anderson was off in Italy, doing the live-action. So, what I did was draw very specific storyboards and later turn them into animatics which are basically storyboards with rough animation added here and there. Even a little like CG modeling. That way, we could be very specific representing how stop-motion animation would by used in various shots; Wes Anderson could review them at his shooting locations. We communicated that way by sending Quicktimes over the internet so there would be no surprises. That was great because I got to work in the fabled Star Wars model shop. I think it’s the only outside project that ILM allowed in their stages! That was great, too, because I had this dream as a kid. I wanted to work on the Star Wars movies and to be in that exact environment, you know!

AV: And you’ve also more recently worked with Henry on his Laïka Animation projects like Moongirl and Coraline.

AV: And you’ve also more recently worked with Henry on his Laïka Animation projects like Moongirl and Coraline.

MC: I was head of story on Moongirl, and Coraline is a stop-motion film for which I did a lot of storyboarding and some co-directing.

AV: Now, can you me about your experience at Pixar, that began with no less than Toy Story?

MC: That was great! I really like working at small, start-up studios like Pixar was, like Skellington was and now it’s kind of the same thing thats happening at Laïka. There were only 40 people, basically, working on the thing and I only worked on Toy Story for about six months because I had to go back to James and the Giant Peach. Pixar was just starting the early storyboard sequences on Toy Story. They were key sequences and it was basically John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Joe Ranft, Pete Docter and I sitting in a room brainstorming what these key sequences would be. There was some test animation going on at the same. That was a pretty amazing experience being at the ground levels of both studios and going from working on one of the first full-length stop-motion features to working on the first full-length CG feature. I think being in San Francisco away from the established in L.A. animation industry helped the projects take on new, ground-breaking methods. Henry Selick and John Lasseter went to the Bay area because here they were able to more daring productions with their talented group of artists and technicians.

AV: Do you tell stories differently knowing they’ll be shot in stop-motion or in CG?

MC: Yes. As far as the stop-motion aspect of Nightmare Before Christmas is concerned, you think more of the limitations of the set, basically. You could do only so much in a stop-motion set although there was very clever usage of forced perspective to make locations deeper or more vast. But you have to be somewhat aware about limited stage space. And also, there were design elements. You have to have very good armature makers to make the metal armatures inside the puppets because the original drawings that Tim Burton did were just lines, sticks, for legs and arms. To get armatures that thin, you really have to have top-notch engineers and armature builders. Those were kind of the limitations we had on that film. Both stop-motion and CG are similar in the fact that you’re building set and environments. You have to flesh out that set in the same way. Currently, you can do more squash and stretch, for example, in CG than in stop-motion (although there are ways to do it in stop-motion now, but it’s top secret for the moment!). They’re different means of expression and you have to take into account the limitations of each one.

AV: How did you work with John Lasseter?

MC: That was good! He obviously is amazing at collecting some of the best people in the business and really would let them explore and come up with lots of ideas. But it’s not only about animators, it’s also about the editorial staff. I remember the end of a scene in Toy Story six months before it came out and there was too much dialog, too many things going on. So, the editorial staff, working with John and the story crew, refined it down to what you see in the final movie which is just the best bits. So, they really encourage lots of story exploration in Pixar. There’s an inside joke at Pixar: they call it story re-boarding instead of storyboarding! A friend of mine, Rob Gibbs, who worked on the Yeti sequence in Monsters, Inc. re-did it from scratch like 32 times or something like that! John Lasseter tends to invest all his time in story in building the story up and keeping the best moments. Not too many people do that.

AV: What kind of ideas did you bring to Toy Story?

MC: Ideas that didn’t go! Which are sometimes just as important. For instance, there’s a scene with Buzz Lightyear and Woody having an argument on the bed. There had been some dialog written in the script and we had to come up with rough staging. But it just wasn’t working. When the scene was presented to the Disney executives, it was very evident that Woody wasn’t a likeable character, especially in that scene. Finding out those things in the storyboarding process allows you to make adjustments and changes in the script. I great example in the importance of storyboarding. I worked a lot with another storyboard artists called Kelly Asbury, who was very influential on the film. I also did some design work on mutant toys, and I think some of those elements made it to the film.

AV: You came back to Pixar to work on The Incredibles, under the direction of Brad Bird this time.

MC: I initially worked with Brad Bird on a project called Ray Gunn, which is a great science-fiction animated feature that was shelved by the studio. I think that it’s Warner Bros. that has the rights. It’s fully storyboarded, with a very beautiful script, but at the end, someone at the top did not want to make it for whatever reason. So, I had worked with him, and also Mark Andrews and Lou Romano on that film. I really liked working with them. So, when I heard Brad Bird was coming up to Pixar to do The Incredibles, I called Mark Andrews and asked him if they needed any story artists. That’s how I started working on The Incredibles. I helped at the early stage of the boarding, which is what I tended to do a lot, coming at the beginning and taking those initial stabs at sequences.

On Incredibles, Brad had probably about half of the script worked on or written when I started, There were a couple of sequences that I took a first pass at. One was E showing Helen the costumes that she designed for the family, where they go through all the machine guns and all that kind of stuff. That was very clearly written by Brad and was playing very well on the script pages. So, my job was just to take some of the art direction that had been done and make that work choreography-wise, with that typewriter type of platform that E and Helen ride on. There was also a sequence about why E would not do capes. E was warning Helen against capes. It was originally Helen that she was warning about capes, not Bob. There was a change in the story, there. One other assignment was Bob visiting Nomanisan for the first time. Brad didn’t have any script pages written for that. It was basically “Bob visits Nomanisan”. So, I worked with Lou Romano, one of the production designers and illustrators to see what they had done as far as the design of the island, to come up with, storywise, how Bob arrives at this island, what he sees. It’s a secret base inside a volcano, as it had been done in a James Bond movie. So, one of the things I came up was the idea that the majority of the base is behind this waterfall that opens up like a curtain. You see that just briefly and it closes up again. So, ideas like that I added to that sequence.

There was a lot of brainstorming on a couple other sequences with Mark and Brad. For instance, how does Bob discover that there’s been other superheroes there before him and how is he going to avoid same fate that they met. So, that’s it: Brad has sometimes very specific vision or script pages that he would hand to you, which is still a lot of fun because he’s open to exploring how those events unfold visually, and then other times you would have just the basic idea like “Bob visits Nomanisan” and it’s up to you to come up with ideas.

AV: What kind of tools do you use for storyboarding?

MC: More and more artists are drawing on Cintiqs now. The Wacom Cintiq is a computer monitor that you can draw on with a special pen. I use it in tandem with Photoshop. Enrico Casarosa and I are actually a couple of the first storyboard artists to use the Cintiq at Pixar, on Ratatouille. We were like guinea pigs! Do you see the animatic of the Edna Mode sequence? That is a sequence pre-visualization style pioneered by Mark Andrews and Andy Jimenez. I still do early passes on paper because it’s still faster for me. Then, I would scan them in. Drawing on a computer allows you to use the same background when you’re drawing on layers, so it’s a time saver because you don’t have to draw the same background every time. With that system, you can see how you boards cut against each other because, if they’re pined up on a wall and you’re going from one to the other, you’re not truly seeing how they cut against each other. So, you can see problems you would normally have to wait till the drawings get to editorial. Also, sending your digital files to an editor is very easy after that. I think Pixar is almost completely converted over to digital.

AV: Your latest participation in a Pixar film was Ratatouille. Can you tell me about your experience on that movie?

MC: I loved that story, the idea that Jan Pinkava came up with, just the simplicity of it: a rat in a kitchen. A rat is certainly the most improbable thing you could find in a kitchen, especially in a fine French restaurant in Paris. To me, it was just a very charming idea and a great idea for a project. I had liked Geri’s Game. So, I spent six to eight months storyboarding and also doing a very complex – probably overly complex – pre-visualization of the opening shot of the film using storyboard drawings that I created and some of the production designer’s drawings for the architecture. In After Effects I made 3D buildings and rooms and moved the camera through them. It was a three minute camera move that took me way too long to make. But it was also one of the pieces that were presenteded to Steve Jobs to help greenlight the film, so I think it was worthwhile. It was interesting: that presentation to Steve Jobs is probably a good indicator of how the storyboarding process is evolving. Because I think Ronnie Del Carmen pitched him hand-drawn boards whereas I had that animated pre-visualization sequence I did on the Cintiq with Photoshop and After Effects.

AV: What was the story like at that very early stage of the production?

MC: There was a first draft of the script written by Jan and the head of story at the time, Jim Capobianco, who is a very good writer and at the same time, you had Enrico and I starting to board those key sequences that I mentioned, one including the opening shot of the film. But all the basic elements were there: it was Remy the rat having different tastes from him family, and wanting to spy on this chef in in a high-end kitchen. When Jan started out, Gusteau was living. He was the chef in that kitchen. There was a lot of interaction between Gusteau and Linguini. I think that Gusteau being a ghost was one of the major changes done, which I think helped simplify the story. But, again, all the basic elements were there in the story that Jan had envisioned, with Remy wanting to prove himself and hiding from most of the humans, with Linguini being kind of his vessel to get into that kitchen.

AV: Seeing your progression, from Space Girl, your first film, that you wrote and directed, to that opening sequence study for Ratatouille, we can’t but think about your directorial talents. Is that something you’re also thinking about?

MC: Yes. It’s partially a desire to tell your own stories, and, having done storyboarding, design and animation for so long, I think it’s a natural progress. However, it’s a very tough road, directing! I’m working on different projects for Laïka in the director role. It really helps to have been a storyboard artist, especially working under directors like Brad Bird, John Lasseter and Henry Selick, where they give you their directions, but also a lot of freedom at times. Helping you grow as you take on more responsibility while storyboarding a sequence. So, I’m thankful to those people who allowed that kind of nurturing to happen!

is available to buy now from Amazon.com

With all our thanks to Michael Cachuela for his time and artworks.

Storyboards by Mike Cachuela. ©Disney.