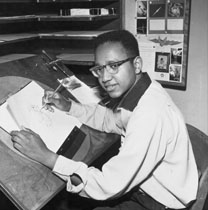

Floyd Norman was born in 1936. 20 years later, he began at Disney as an inbetweener on Sleeping Beauty, The Sword in the Stone and Mary Poppins, as well as many of the Studio’s short cartoons. But he’s more acknowledged for his numerous contributions to Disney as a storyman (even though he never had any intention to do that job!), creating stories for The Jungle Book, recently released in a 2-disc Platinum Edition DVD.

From then on, he contributed to many Disney classics, and his expertise on everything concerning animation and his knowledge about Walt’s time makes him one of today’s essential “go to” people when it comes to Disney lore. That’s the reason he was called upon to get involved in some of the Mouse’s recent projects, such as Mulan and Dinosaur, and was in demand at Pixar to help flesh out stories such as Toy Story 2 and Monsters, Inc.

No surprise, then, that he was made a Disney Legend last October 2007, a more than fitting honor for us to use as an excuse for look back on a legendary – and genuinely nice – artist’s extraordinary career in animation…

Animated Views: What was your reaction when you learned you had been nominated as a Disney Legend?

Floyd Norman: Well, surprise! Always surprise…amazement…that would be it. It was just such a shocking surprise. It’s a great honor, of course, and it’s kind of hard to evaluate one’s self. I never thought that I would be selected for this particular honor, but it’s just a wonderful thing when it comes your way!

AV: The Disney Legend award celebrates the fact that you were part of Disney history. How did you arrive at the Disney Studio?

FN: I arrived in February of 1956 as a young kid just out of art school. Back in those days they had what was sort of a training program for potential new employees, and what they would do, they would bring in young kids and put them through a month-long training program. Those who came through that program and showed they had promise for a career at Disney, then they would be hired on as sort of a temporary employee. And so I was lucky enough to be selected as part of that training program, and I did my month of training, and then after that I found out that they were going to keep, I think, around seven or eight of us, and they kept us on.

FN: I arrived in February of 1956 as a young kid just out of art school. Back in those days they had what was sort of a training program for potential new employees, and what they would do, they would bring in young kids and put them through a month-long training program. Those who came through that program and showed they had promise for a career at Disney, then they would be hired on as sort of a temporary employee. And so I was lucky enough to be selected as part of that training program, and I did my month of training, and then after that I found out that they were going to keep, I think, around seven or eight of us, and they kept us on.

AV: What were among your first assignments?

FN: They tried to start out all the trainees on simple things. The first thing I remember working on was The Mickey Mouse Club, which was a popular TV show at the time, and I worked on the Disneyland television show. Walt Disney has just gotten into television, and so I was on the TV show that was going and they were still doing animated shorts. So that’s how most of us started out, doing what was considered, I guess you’d call, the simpler kinds of animation. Things like that, for television, because it took a while before one could graduate up the ladder to work on the feature films.

AV: And sure enough you were soon moved to the Sleeping Beauty project.

FN: Not so soon, but about a year or so, maybe a year and a half before I was able to be worthy, I guess you might say, of working on Sleeping Beauty. Back in those days the feature crew was considered the most experienced, the most capable. It was really an honor to be chosen to work on a feature.

AV: What did you do on Sleeping Beauty?

FN: Well I was what they called in those days an animation inbetweener, which means you were an assistant. I should explain that back in those days the animation crew were fairly large. There was an animator and the animator would have assistant animators, and those assistants would have assistants, and so all down the line you were part of a pretty sizable crew who worked on these films.

AV: As an inbetweener, which specific scenes do you remember working on?

FN: On Sleeping Beauty some of the early scenes I worked on involved the horse, I think his name was Samson. I did some work on the Prince, and then about six months or so after that Disney put together units to focus on certain characters, so I became part of the crew working on the three fairies, and that was going to be by assignment throughout the duration of the film. Because to get the films done they would set up these units and each unit would focus on a particular character. So for nearly two and a half years, for the remainder of Sleeping Beauty, we focused on the three fairies, Flora, Fauna and Merryweather.

AV: In an interview that you did that was published in Didier Ghez’ Walt’s People, I quote you said: “After working on Sleeping Beauty a Disney artist was qualified to have their hands on anything”. Can you explain that please?

FN: Back in those days the training amd the demands of the art was so vigorous that you really had to know your stuff to do that particular kind of work. So the artists were really put through their paces, and the people you worked for were very demanding. I often joke about that they were concerned about the length of an eyelash on a character, there was great attention to detail, and so after going through that, that kind of work, one would be qualified to do pretty much anything. Just because the work was so demanding, and if you met that standard, you could pretty much work on anything.

AV: How did you meet the Nine Old Men and what kind of a relationship did you have with them? Were you closer to Ward Kimball or Frank and Ollie?

FN: Well, to tell you the truth, back in those days you really didn’t have any interaction with the Nine Old Men. When you were part of an animation crew, you were generally working for an assistant who worked for another, higher assistant and they worked with the animators, that might have been one of the Nine Old Men. So we seldom even saw the Nine Old Men…we certainly didn’t interact with them because we were certainly not on that level. You know, it’s kind of like there was a pecking order and they were at the top and we were at the bottom. It wasn’t until years later that I got a chance to meet and work with the Nine Old Men, guys like Frank Thomas, Milt Kahl, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Ward Kimball and others. But that didn’t come until after I’d been at the Studio probably for at least about four or five years.

AV: You mentioned Milt Kahl [right], who I understand you worked closely with for The Sword In The Stone?

FN: That’s correct, yes. After finishing One Hundred And One Dalmatians I was going to sign to work with Milt Kahl on The Sword In The Stone, and that was one of the few features that I actually worked on from start to finish, as part of Milt Kahl’s unit.

AV: Milt is obviously very famous for what we’ll delicately refer to as “his temper”.

FN: Milt Kahl was quite an interesting figure all by himself! You can talk about being a legend, he’s legendary. Out of all the extremely gifted artists, he drew extremely well. He was a fantastic draughtsman. He was also known for his volatile temper. He was a very dynamic, very outspoken gentleman who had no qualms about speaking his mind and making his feelings felt. So he was quite a character all by himself.

AV: What was your working relationship like with him?

FN: My relationship was fine actually…as young kids we were all frightened of him! He could be a very scary kind of guy. But as the years went on I found that I had a very good relationship with Mr Kahl. We didn’t call anybody “Mr” by the way, everybody at the Studio was on a first name basis, even though they might have been old enough to be your father you’d still call them by their first name. So my relationship with Milt was very good. I think it was because I was able to make him laugh! I often feel my ability for funny gags and make people laugh seemed to help me disarm even the most ferocious characters at Disney, you know! I think make them laugh and I became their friend that way.

AV: In The Sword In The Stone do you have any favorite scene that you particularly remember working with Milt on?

FN: Oh well! I guess I should, but since I worked with Milt throughout the entire film it’s difficult to choose one. I will say that one of the sequences I felt I had the most fun with was with Madam Mim, she was our villain, the crazy little witch, who was very colorful as well as a scary character. Working on that with Milt Kahl was probably the character I enjoyed the most.

AV: The next film on which you worked was Mary Poppins and that was with Frank Thomas?

FN: No, I never actually worked with Frank Thomas. Frank and the other of the Nine Old Men were all in the same area, but I didn’t actually work with Thomas on that film. I certainly saw him on a regular basis, and I saw his work, but when I think back to the animators I worked with, there was John Lounsbery, Milt Kahl…there were quite a number of others I might have worked with, but not Frank Thomas, even though I did see Frank quite often and certainly I enjoyed his work.

AV: What did you do on Mary Poppins?

FN: Again I was an assistant animator. What the assistant did was to take the scenes from rough animation that was provided by the animator and then finalise that animation. That is, put in all the extra drawings that might be necessary through the final clean up drawings, because the drawings start out very loose and very rough. They have to be finalised, so that they’re very clean, finalised drawings. So that was my task on Mary Poppins. They hadn’t made me an animator yet, so I wasn’t doing any animation as such, but I was working on the animated scenes by finalising the rough drawings.

AV: Whose assistant were you? Could it change during the production of a film, for example on The Sword In The Stone did you go from Milt Kahl to another animator or was it continuous through the production of a film?

FN: I assisted a number of animators. Everyone from Milt Kahl, to Art Stevens, to Ward Kimball. But generally they liked the same people. We thought of animation like a team, so in the case of my working with Milt Kahl on The Sword In The Stone I only worked with Kahl on that particular film. That’s the way the Studio preferred things to work out. There may be occasions where an assistant might work with a number of different animators but that was rare. They usually liked to keep a group intact. So if you were assigned to one animator the chances are you were going to work with that one person throughout the duration of a film.

AV: And then after Mary Poppins you went from animation to the story department.

FN: Yes, around that time, I guess. There were a lot of things going on besides the feature films, and I know I did work on other things after Mary Poppins. I think I was working on cartoons before being sent to story.

AV: How did you end up in story? Was it your personal choice?

FN: Oddly enough it was not my personal choice! The story department was a highly coveted position at The Walt Disney Studio. A lot of people wanted to be in story but could not even get near to story. In my case I wanted to be an animator, I had no aspirations of working in the story department, and yet somehow one day my boss called me in and told me that I would be put upstairs into the story department. And honestly I have no idea why I was given that assignment! But back in those days you did what you were told…I was told I was being taken from animation to go work in story, because that’s where they wanted me, and so that’s exactly what I did.

AV: And this was on The Jungle Book?

FN: Yes, right, it was on The Jungle Book. The master story man, who had worked at Disney’s since the 1930s, had just quit the film.

AV: You mean Bill Peet?

FN: Right. He just quit; he got into an argument with Walt Disney and walked off the film. And so the film had to be totally redone because Walt Disney was not happy with it. He wanted to do a whole new take on The Jungle Book and I was part of that new crew that was going to come in and reshape the movie. But how I got that job I honestly do not know. I speculate that it might have been one of the senior animators that might have recommended me…I don’t know, it might have even been Walt Disney himself.

AV: With Bill Peet’s version, we’ve heard about a much darker, serious version. Is that correct?

FN: Yes it was. I can’t tell you a great deal about it because it’s been so many years. I remember going to Bill Peet’s office and looking at his take on the book and can tell you one thing, that it was closer to Kipling’s original story than to the film we eventually made. That was the big argument Walt Disney had with Bill Peet, that he didn’t want to do Kipling, he wanted to do his own version of The Jungle Book. He really wanted very little from the Kipling story, other than the basic overall premise and the characters. As far as the way that Kipling had told the story, Disney just felt the story was much too dark…he wanted more lightness, he wanted humor, and that’s why he and Bill Peet kind of got into a fight, over the story.

AV: Did your version go through changes? There was a deleted character, Rocky the Rhino, for example that was in an early version.

FN: Well you know, in the development of a Disney film, a lot of times we try out many things in developing the story. Rocky the Rhino was a sequence that was in the film; a sequence Walt Disney didn’t particularly care for, and so that sequence was cut from the movie. But that is not at all unusual, it happens all the time.

AV: Do you remember any other sequences that were deleted?

FN: To be quite honest, there were probably other scenes cut from the film that I suspect we can no longer remember. I do know that the reason that Rocky stays in mind is because that was a sequence that Walt Disney particularly disliked. And so that one kind of stands out in my mind, although like I said, all the time many, many sequences are cut from a film during the story development, so it’s not at all unusual. It’s just part of the filmmaking process.

AV: When you were coming up with stories, was this using storyboards? Can you tell us about that process?

FN: The Disney Studios has always developed their stories on the storyboard rather than on script pages. It’s known as visual storytelling, and that is instead of a writer describing the story in words, as any writer can usually do, we would actually start with artwork, and as opposed to starting out with dialogue, or words, or descriptions, we would actually start drawing. And then those drawings would be arranged on a board in sequence, and that was how the story process at Disney began. It’s a process that began in the 1930s, a process that continues to this day. There is more of a reliance on scripts today…unfortunately that came to Disney in the early 80s when Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Because they came from a live-action background they were used to having scripts and so they demanded that the animated films have scripts as well. Although to me I feel that’s a handicap, not an aid. It really doesn’t help us much, in my opinion. I feel that the story development process on storyboards is still far superior to the script page.

AV: How did you prefer to work in the storyboard times?

FN: You can work in any number of ways. A lot of story men like to work by themselves in a large room…Bill Peet worked that way. Others like to collaborate, they like to work in a room with another artist so they can toss ideas back and forth. And sometimes you may even work in a large room with five or six people and shoot around ideas. So the process involves everything from being a single solitary artist working by his or herself, to a room full of people all collaborating, tossing ideas back and forth.

AV: What was your process…did you work alone or collaborate with other story men?

FN: I like to work with other people around. Sometimes there are times when one might want to work alone, and there’s nothing wrong with that, although if I had my preference, I would tend to want to work with others, because I like to have somebody to, as they say, bounce the ideas off of. I like to throw out an idea and see how people respond to it. So I probably prefer not to work alone.

AV: Who did you like to work with? Larry Clemmons, or others?

FN: Larry Clemmons was one of the writers at Disney although I didn’t exactly work in the same group as Larry, he and I worked separately. But my favorite collaborator was a Disney veteran known as Vance Gerry [standing, right]. He was the person I worked with on Jungle Book. The two of us shared an office and we were both collaborators.

AV: And you would both throw ideas at each other and see what worked.

FN: Oh yes, that’s how the process works. You try things that, if they don’t work you throw out, things that you good, that are worth keeping, you keep those ideas, and that’s how the whole process comes together. Hopefully you’re keeping the best of what you come up with. It’s kind of difficult to explain how it works. You sit down and you start drawing, and you’re trying to open yourself up to ideas…possibilities, and a way of letting your imagination roam. It’s difficult to explain the process because I don’t have any methodology; I just get to start thinking, start drawing, start trying things and just try to see what works. And if you get something good, then you are very pleased. If you get something that’s not so good, then you start over again. But the process is like any kind of process…you sort of have to allow it to happen, you can’t force it, you can’t make it happen.

AV: Do you have a favorite sequence that you did for The Jungle Book?

FN: Oh, that would be very difficult to tell you. As a story artist you really don’t have any favorites, and a film is a very collaborative process so it’s difficult to take ownership over anything, really, because you are involved in a film with a dozen or so other people and it’s difficult to say ‘they did this’ or ‘I did that’. Sometimes you don’t even remember what you did. I do know, to choose an example from The Jungle Book, that the idea for the snake and the song came initially from Larry Clemmons. Then, once we showed that to Walt Disney, Walt would begin to embellish it, and it was Walt Disney who decided that he should have a song. And when the Sherman Brothers had written the song for us, then we were able to go back to that sequence and approach it again and work on ideas. So it’s a very open, it’s a very dynamic, it’s a very organic process and you’re just trying things to see what works.

AV: You mentioned the Sherman Brothers. Did you collaborate with them or did they just provide the song when it was done?

FN: We collaborate as much as possible, we talked with them and listened to the music, so there is an open collaboration. I like both the brothers very much and worked with them on more than one occasion. That’s one of the nice things about being at the Disney Studios, is that you’re with creative people that are all willing to share their ideas, be it words, be it music, be it pictures.

AV: The meeting between Mowgli and Kaa also leans heavily on dialogue, so how using the visual storytelling method, how did you shape such wordy scenes?

FN: We start out, and this is the way Disney worked at least during the time Walt Disney was the head of the Studio, we always started out with a basic story outline. That outline usually came from our writer Larry Clemmons. From that rough, bare bones outline we would take the idea and flesh it out visually, sometimes adding bits of dialogue where needed. Once that was done, Larry would come back and look at what was there, and things undoubtedly had changed, things had gotten more involved and more developed, and then Larry would write more dialogue for the characters, where he felt it was appropriate.

It’s kind of like the writer is working with the story artist…we are all basically screenwriters, and we are basically developing the storyline, both visually and with dialogue. It’s give and take, back and forth. We confer with the writer and the writer confers with us. Once we have that done, then we show that finished board, complete with pictures and words, to our director. In this case our director was Wolfgang Reitherman, often known as Woolie, his nickname. We would show that to Woolie, and if Woolie thought that the board was presentable, and he was happy with it, then he would show it to Walt Disney. And that became pretty much the process, the way all story development on films worked at Disney.

AV: When the boards moved to the story reel, were you involved in the recording of the voices?

FN: Sometimes we are, sometimes not. Usually that becomes the job of the director. It’s the director who goes to the recording stage with the actor, to sit down with the actor to make sure they get everything right, to make sure every inflection and every nuance fits. On occasion though the story artists would attend a recording session, not so much that we’re there to advise the actor, but because we just want to see how the whole thing is coming together. So for instance when they were recording Sterling Holloway, the voice of Kaa, I did attend those recording sessions, but not to director the actor because that’s the job of the film’s director. I was just there to see what was going on and to see how things were all coming together.

AV: What memory do you have of that time? Sterling Holloway was such a great artist.

FN: Oh, my-my! Well, my first awareness of Sterling Holloway began when I was a child. That’s a long time ago! My mother took me to see Dumbo when I was a little kid, I might have been five or six years old, but that was my first awareness of Sterling Holloway, playing the part of the Stork in Dumbo. As the years went on, I began to recognise his voice in other Disney films because he was always doing the voice of some character, you know, maybe a small part, maybe a bigger part. In the series of Disney films I can’t even remember all the voices Sterling did. He became a pretty regular fixture at the Disney Studio and it was not unusual to see him strolling the hallways of the animation building. Sterling Holloway also had a career in films, I think in the early 40s he appeared in a number of movies, and TV shows in the 50s.

He was never a big star, but he was kind of a supporting comedy player. I think he was probably best known for his distinctive voice, which seemed to really fit animation and I think that’s why he was used so often at Disney. So I pretty much got used to seeing Sterling Holloway in the hallways at the Disney Studio. He was always there to recorded something or other for some film or other. He was amazing…he just seemed to fit certain characters. When we were trying to find the voice for Winnie The Pooh, somebody suggested Sterling Holloway, and sure enough Sterling Holloway’s voice just seemed to be a natural fit for Pooh Bear. And yet he was also – he didn’t really alter his voice at all! – it was the same voice that he used for Kaa in Jungle Book, which was pretty much the same kind of raspy squeaky voice, but only a little more menacing.

AV: And the same again for Sir Hiss, in Robin Hood.

FN: Actually, Sir Hiss was done by a different actor…the British actor Terry-Thomas. It’s kind of hard to keep track of all these different voices but, yes, Terry-Thomas did the voice of Sir Hiss in Robin Hood, another film I worked on as an animator. He and Peter Ustinov were the two villains in that particular film, and Terry-Thomas was the foil for Prince John.

AV: When you worked on the storyboards, were you aware of the character designs? Were you able to use those designs to represent the characters?

FN: Only in a very light way. Keep in mind that as story artists our main concern, and this was Walt Disney’s focus as well, was to develop the story and the characters, not to worry about the particular look of the characters or the design of the characters. That job fell to the character designers and the animators in particular. Our job was to certainly represent the characters on screen, but there was no real effort made to draw them exactly the way Milt Kahl, say, would draw Shere Kahn, or exactly the way Frank Thomas might animate a character. The characters are easily recognisable, if you’ve seen any of the story sketches, you know pretty much what Mowgli looks like and what Bagheera the panther looks like, but we really made no real effort to emulate what the animators were doing downstairs. As long as Walt Disney was able to recognise what character we had on screen that was really all he needed, that was close enough.

AV: When you came to the story department, did you feel your animation background helped you to bring movement and energy to your storyboard illustrations?

FN: I’ve always felt, and maybe it’s just me and a few of my colleagues, but a handful of us have always felt that if you’re going to work in animation you should pretty much have done every job in the animation process. You should be able to paint backgrounds, you should be able to do layouts, you should be able to do animation, and story, and in some cases – and I’ve done this – even be able to do voice acting. I think considerable knowledge of the animation process is a necessity, because I think any one particular skill informs the other skills. In other words I took what I’d learned in animation and applied that to story. I take what I learned in story and apply that to animation, and into layout and into background and to everything else. I think to be a well-rounded animation artist I actually feel one should be able to do every job if one had to. Now people tend to be particularly good in one specific aspect of animation, there are some guys that are just natural animators. Some people have a skill as a background artist, they are just gifted in the knowledge of color and composition. So we all can have our specialties and we all tend to end up in one niche or another as the job necessitates, but knowing the job thoroughly and being able to do every job I think will make you a better animation artist.

AV: During The Jungle Book, it’s well known that Walt Disney was also involved in his EPCOT project and the New York World’s Fair. From your perspective, how involved was he on the film…did he supervise any story meetings?

FN: Yes he did. I’ll let you know a little bit about Walt Disney. Walt Disney ran his Studio, he was involved in everything, and I always have to emphasise I do mean everything. Nothing that came out of that Studio ever came out not having Walt seeing it and approving it. He was involved in everything involving the theme park, the television shows, the movies, the books…whatever it was his involvement was there because I think Walt Disney felt that his name was on the product. That product represented him, his philosophy, and so he was involved in everything.

In terms of filmmaking, and animation specifically, his greatest concern was story. That’s where he focused his attention, because with Walt Disney the story was what was going to make or break the film. He didn’t worry so much about visiting his animators because he knew they were the best in the world, he didn’t have to supervise them. He didn’t have to worry about his layout artists because he knew they were also the best, and his background artists were the best in the business. But he did supervise story because that was where he could have an impact, that was where he could influence the film.

So the only department Walt Disney truly paid attention to, when it came to animation, was the story department. And indeed he would come to meetings, every sequence in the film would be pitched to Walt Disney. He would be there in the room and you would have to pitch that sequence to him, and he would then approve it or reject it. Sometimes he would make suggestions on how to improve it…sometimes he would completely decide to cut the entire thing, just throw it out. It was up to his discretion. He was the boss, he was the final word. It truly was Walt Disney’s Studio in every way. He was the man you had to please. If you didn’t please him, then you weren’t doing your job.

AV: How did you feel in his presence?

FN: Initially, when I first came to the Studio in 1956 and we were all young kids just out of school, he had already reached kind of a legendary status and so we were all very much intimidated by Walt Disney as you can imagine. Although I must tell you, like anything else, after being around a person for a number of years that tends to wear off. So by the time I was doing my work on Jungle Book I had already been at the Studio for nearly ten years, which means I had been observing Walt Disney over that ten year period and had pretty much gotten used to him. So I was no longer trembling and intimidated or afraid of him the way I was when I first came.

However we still did have an enormous respect for him…he was a man in his sixties, I believe at the time we were working on Jungle Book he was around 65 years of age and of course I was still in my twenties, I was still quite young. So we had enormous respect for him but I certainly wasn’t afraid of him, and certainly was open to any suggestions or improvements that he had to make. It was a good relationship and I have to always tell people, ‘don’t get the impression that I was buddy-buddy with Walt Disney’, because I certainly wasn’t. I mean, keep in mind he was a man of nearly 65 years of age, I was a kid in my twenties; the two of us had very little in common, so we certainly didn’t hang out together, we certainly didn’t have coffee together or anything like that. That was for his peers. But I was in meetings with Walt Disney and had a chance to hear him speak and make his suggestions first hand.

For a young kid coming up in the business, that alone was a tremendous opportunity, to be in the same room with Walt and hear him make his suggestions, that was a rare opportunity. It was one I didn’t take lightly; I knew that if I was in a meeting with Walt Disney, I was a lucky person to be there because not everybody was even able to attend a meeting with Walt Disney. Some people would just hear about it afterwards, or they would get notes about what went on, but to be in the room with the man himself…very few people got that kind of an opportunity and for me I think that was just lucky. To be a kid and to be so young, and yet to be in meetings with Walt Disney at that time was certainly a special thing for me.

AV: Absolutely! After dealing with story you moved back to animation. How did that happen?

FN: It’s a funny thing. I never had any particular love for story. I certainly had a good deal of respect for storytelling; I just didn’t feel it was my strongest ability in this whole process. I did what I did because it was a job, they told me that this is what you’re going to do, and then you do the job you’re given. So I went back to animation after Jungle Book because I still wanted to be an animator! I was still very much in love with animation. I wanted to animate, so I went back and I did animation for some years after working on The Jungle Book, having enjoyed my time in story, but thought “now I’ll get back to doing what I really want to do”. And yet, somehow, over the years, for some reason or other, I kept getting pulled back into story!

I remember I went to work on a movie and I had signed on to work as an animator, and I was looking forward to that, and then the boss called me in and said “well, we don’t have any animation…it’s going to be coming up soon, but in the meantime would you help us out doing storyboards?” He said “I know you know how to do it”, so I said “sure, sure, I’ll help out”, you know, “sure, I’ll do some storyboards”, and lo and behold I never got back to animation! So more and more it seems that I had found the place for myself in animation, and that seemed to be the story department, because it seemed I kept ending up doing story! I would always end up going back to story. I would do some animation, I would do some layout, but sure as anything I would find myself back in the story department doing storyboards. After a time I realised, well maybe this is what I’m good at, so I’ll just keep on doing story.

AV: You did get back into animation for Robin Hood though?

FN: Yes. I had left Disney for a time in the 1970s, and they asked me to come back to work on Bedknobs And Broomsticks. That was a live-action musical but it did have an animation sequence in the middle of the film, the Soccer sequence, and Ward Kimball was directing that sequence. So I came back to work on that and then I was going to leave again. Then Robin Hood was the next feature film and I ended up working on Robin Hood, around 1972-73 I guess. And then I left Disney again, because at the time I just wasn’t real happy with the way things were going. The Studio was changing, and I felt changing not in a way that would benefit me, so I thought it was time to move on. Never knowing that I would be called back yet again! I have a habit, throughout my career at Disney, of leaving Disney, and being called back, then leaving again and being called back! This was a continual thing in my career! I’m leaving the Studio and then again always ending up back there. I guess it was where I was meant to be, I suppose.

AV: You eventually settled down again at Disney during the Eisner era to work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame?

FN: Well, this is the way it happened…I was working once again at other studios on other projects, and this was around 1983. The Studio called me and they wanted to hire me back, and I said no, I’ve got another commitment so I can’t take the job. And then they called me back again in the summertime: “would you take the job at Disney?” and I said no, I’m still doing something else! Then they called me a third time around the end of 1983 and I said “oh, okay, I’ll try…I’ll come back and take this job”. And that was a job in the publications department, where they did the books, the comic books and the comic strips. So that was the job I took in 1983. That was just prior to the arrival of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells, they came onboard in the spring of 1984, and ran the company. I continued to work in the publication department, eventually doing the Mickey Mouse comic strip for King Features Syndicate, and I was there, surprisingly enough, for ten years! I had only planned to be there a couple of years because I just wanted to take a break from animation and do something different, but I ended up staying on for a ten year period, from 1983 up until 1993, and it was in 1993 that I returned to animation to work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame.

FN: Well, this is the way it happened…I was working once again at other studios on other projects, and this was around 1983. The Studio called me and they wanted to hire me back, and I said no, I’ve got another commitment so I can’t take the job. And then they called me back again in the summertime: “would you take the job at Disney?” and I said no, I’m still doing something else! Then they called me a third time around the end of 1983 and I said “oh, okay, I’ll try…I’ll come back and take this job”. And that was a job in the publications department, where they did the books, the comic books and the comic strips. So that was the job I took in 1983. That was just prior to the arrival of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells, they came onboard in the spring of 1984, and ran the company. I continued to work in the publication department, eventually doing the Mickey Mouse comic strip for King Features Syndicate, and I was there, surprisingly enough, for ten years! I had only planned to be there a couple of years because I just wanted to take a break from animation and do something different, but I ended up staying on for a ten year period, from 1983 up until 1993, and it was in 1993 that I returned to animation to work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame.

AV: What was that like?

FN: That was very exciting. I really enjoyed that film. Keep in mind that animation had gone through a lot of changes…the department had almost been totally rebuilt from top to bottom, because all of the old-timers had either since retired or passed on. And so here was a brand new animation crew of young people, and they were doing some very interesting work. And even though I wasn’t working with them because I was working in a different department I always made a point to stay in touch, to know what they were doing, and to work with them in any way I could. I did a lot of the adaptations of the feature films into published material, so that meant taking whatever animated feature was in production and we would do the books, comic books and comic strips all based on this new Disney feature. I never had any intention of returning to animation, I thought that my future was going to be as a writer in the publishing department. But lo and behold it got changed yet again and they invited me to come back and work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, which I took because I thought it was the most unusual project, and I’m always excited by projects that are either unusual or risky, or crazy or whatever.

I thought that doing The Hunchback Of Notre Dame in animated form would be a real challenge. The director was a friend of mine – in actual fact the director was a kid that we had hired some ten years earlier right out of art school! So since I already knew him, and already knew his talent and ability, I decided to return to Feature Animation to work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, which I saw as my final film. I was just going to return to animation to do this one movie. That was my plan, I was going to do The Hunchback and then move on. Well, on finishing my work on The Hunchback Of Notre Dame they asked me if I would stay on and help them on another film that they were doing called Mulan. They were having difficulties with the story on this film, this was in 1994. So I went over and began to work on Mulan, thinking that I would leave after I finished work on that film. But while working on Mulan, George Scribner, a director, was developing another film, a very unusual project that would combine CG animation with live-action, something totally unique, it hadn’t been done before. He asked me to come over and work on his film, which was called Dinosaur. So I ended up working on Dinosaur for 14 months and then I had a visit from Ralph Guggenheim of Pixar Animation Studios, and he said “we’re short-handed, we’re a very young studio and we don’t have enough animation story veterans on our crew. Would you be willing to come up to Pixar and help us on this new animated feature called Toy Story 2?” So that meant moving up north, up to the Bay area. A lot people have families in the Southland, they had kids at school and didn’t want to move up north. I was in a position to go because my kids had already grown up…I didn’t have anything to necessarily hold me down, so I said “sure, I’ll move up north and help you on your movie”. And that’s how I ended up at Pixar, working on Toy Story 2.

After that, I got another call from Pixar and they said “would you help us out on Monsters, Inc?” Keep in mind that I was now living up north in San Raphael, my wife was down here in Pasadena, and so I said “I’ll have to ask my wife. If she says I can work on your movie then I’ll do it, but if she says no then it’s time to come home. I’m going to have to respectfully pass on your offer”. So my wife says I could work on Monsters, Inc, and so I did! And that was my last Pixar film, and after I finished my work on Monsters I was able to return home. That brings us up to the year 2000, when I returned to Disney, and I worked one more year at the Disney Studio before retiring from animation in that same year, around the fall of 2000. That was pretty much the end of my career at Disney, at least my full time career at Disney because I found myself, even after I retired, going back to the studio to help out on various projects, and I guess I worked on any number of projects as a freelancer or consultant. So I find myself still connected to the Disney Studio one way or another, even though I’m retired. Sure enough I find myself in the studio a couple of times a week, even now, so I guess I’m kind of a fixture around the place!

AV: Your recent credits include The Tigger Movie and Home On The Range.

FN: Yes, oh yes I worked on Tigger and in early development on Home On The Range.

AV: There was also a title that was never released, called Wild Life?

FN: Wild Life! Yes, that is correct. Wild Life was a film that was in development…I started on the film in January of 2000. The film was actually shut down in the summer of 2000, and the film was never made, it was never produced, because Roy Disney, the nephew of Walt Disney, thought that the film was a little too “sophisticated”, I guess to be kind about it, that’s the best word to use, for Disney’s family audience. And Roy Disney said that it was a film that Disney should not be making. So the film was shut down in the late summer of 2000.

AV: What was it about?

FN: Believe it or not, it was an animated film about a night club! A night club which is not exactly the kind of film you would take the children to see. It was probably not the best of ideas.

AV: When you came back to Disney animation for Hunchback, what kind of relationship did you have on that? Did you bring the classic Disney tradition to what the younger generation were doing?

FN: Yes, I tried to, I tried to. I don’t want to force my ideas on anybody, but if the younger people have questions about the way things were done in years past I’m always happy and willing to pass on whatever I know, whatever I’ve learned, because I do think that this is an art form where the older members pass on what they’ve learned to the young kids, and I know that when I came to Disney as a kid, still in my 20s, I learned so much from the animation veterans who had been doing this stuff for some 20 or 30 or 30 years. You can’t discount that experience and they helped me immensely. So I try in return to pass on whatever I’ve learned to a new generation of animated storytellers, and that was primarily why I think Ralph Guggenheim asked me to come up to Pixar to work, because they were a young studio and they were young kids just out of school, just the way I had been some 30 years earlier. So whatever I could give to them, to help them become more effective storytellers, I was happy to pass on, because as I said, the old guys taught me and so when I became an old guy I was certainly happy to teach the young kids who were finally making their way through. It’s a continual giving, and hopefully one day these same kids, as they grow older and more mature, they will pass on what they’ve learned to a younger generation.

AV: What would be the most important thing that you learned from the masters, or Walt Disney, that you particularly strive to pass on to the new generation?

FN: Well I think what I’ve learned from Walt Disney, and I think what Pixar also learned from Walt Disney, is that when you make a movie, you’ve got to tell a story that’s going to engage the audience. You want a story that they can connect with, that they can relate to, that’s going to touch them. Though it may sound corny, I always say “a good story is a story that makes me laugh, and it makes me cry”. I often feel if I can get those two ingredients in a story and do that effectively then I’ve done my job, because that story, and the characters within that story, should really touch you, I mean you should be able to relate to those characters, you should be able to relate to their situation. Even though it may not be yours exactly, you are going to connect in some way with that character, whether that character be a man or a woman or a bear or a skunk. There’s an amazing connection with the character that makes that character seem to live, and feel, and think. When you make that connection and the audience makes that connection with a movie, you’ve done your job, and that’s what Walt Disney always wanted.

Walt Disney wanted a story that would engage him…that would pull him in to the story. If your story fails to engage the audience then you have failed as a storyteller. You’ve totally failed, because you have to believe that character is real, you have to know what that character is feeling and thinking, and that’s what makes you connect to a bunch of colored drawings on the screen. In other words, those images on the screen that are not real at all, for that time before very real, living, breathing, thinking beings, and you’ve managed to do all that with just a bunch of colorful sketches, or drawings, or CG models. You put them up on the screen and you’ve made them seem alive, and everything they feel and do you relate to. If they get hurt, it hurts you, if they have great joy then you have joy. It’s just what we as storytellers try to do. We have to engage our audience and if we fail to do that then we’ve failed to do our job as writers.

AV: Are you bringing your expertise to any current Disney project?

FN: I’m not bringing any expertise to any Disney project at the moment, although I remain open to whenever they want to call me! I’m certainly here, and they know where I am if they need me they’ll give me a call. As a matter of fact they did call me a couple of months ago – I almost forgot that – because they were developing something, and I was unable to work with them at the time because I was already committed to a television show that I’m currently doing, and I’ve got to wrap that up before I move on to anything else. I’m just too old to work on multiple projects at the same time! When I was younger I could balance two or three projects, but now I’ve got to take it one at a time. So I’m presently working on a TV show for PBS that’ll be on the air next year…that’s what I’m doing at the moment. So no Disney projects at the moment, but that doesn’t mean that there might not be one in the future!

AV: We hope so!

FN: Yeah, I hope so too. I like working with them!

Our special appreciation to Floyd Norman for his participation in this interview and to Didier Ghez for his great help.

This article was originally published in French at Media Magic. It is reprinted here by exclusive arrangement and with express permission from its author, Jérémie Noyer. English version ©Animated News & Views.