Walt Disney Pictures (1939–1995), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (May 18 2004), 2 disc set, 345 mins plus supplements, 1.33:1 original full frame ratio and 1.66:1 anamorphic widescreen, Dolby Digital Mono and Surround, Rated G, Retail: $32.99

Storyboard:

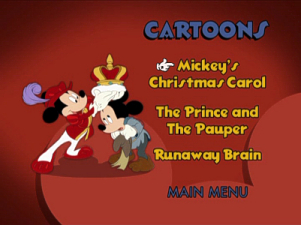

This remainder of Mickey Mouse’s animated cartoon shorts completes his entire filmography on DVD, right up to the comeback theatrical featurettes of Mickey’s Christmas Carol, The Prince And The Pauper and Runaway Brain, presented on home video in their original ratios for the very first time!

The Sweatbox Review:

On May 15 1928, in a small theater in Los Angeles, Walt Disney, his brother Roy and their partner Ub Iwerks, with a simple piano accompaniment by Carl Stalling, previewed the first in a series of cartoons that would go on to change animation as it was then known. Their film featured a character with personality and a real inner thought process – a rare thing at the time. The cartoon, Plane Crazy, was deemed a success by its three creators, even if it didn’t exactly cause the audience to stand and cheer. That would come, on November 18th later that same year, with the third cartoon to feature Mickey Mouse, Disney’s “all-new” star. From its first screening, Steamboat Willie was an instant smash – the first cartoon released that had a synchronised soundtrack attached to the film itself. The two previous Mickey films, Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Goucho, had soundtracks written for them and re-issued on wide release. Immediately, Walt, Roy and Ub were in the Mouse business – the beginnings of the Disney Studio as we know it.

Mickey made Steamboat Willie’s first, immortal, happy go lucky whistle 75 years ago, and the Disney Studio celebrates its leading star and company figurehead with this conclusion of a two part DVD exploration of his color films. In fact, if this new and latest addition to the Walt Disney Treasures line had debuted on its original date of December 2 2003, it would have been literally just days shy of hitting that exact 75 year landmark – and what a perfect way to celebrate Mickey than with another career retrospective? As it is, the set does at least arrive in Mickey’s 75th year, and so far, it has to be said, is the high point of the celebrations (the fun DTV movie The Three Musketeers is also available this year, though Mickey’s first CGI venture Twice Upon A Christmas certainly means that this Treasure collection remains the highlight of the year)!

Split, as always, over two packed discs, Mickey Mouse In Living Color: Volume 2 finishes off the Mouse’s theatrical filmography and brings us bang up to date by including his “comeback” featurette appearances and even touches on Mickey’s appearance in Fantasia/2000 (though, for good or bad, not the Musketeers or Christmas titles). The set starts way back in 1939, picking up where Volume One left off, with the final cartoons originally produced – and voiced – by Walt himself. After a series of films in which he played second fiddle to Donald and Goofy, Mickey’s later films returned to the simplicity of adventures featuring just himself and Pluto, simple scenarios that marked a return to Mickey’s black and white roots. Some of these films are among the best in Mickey’s line up and they continue to play amazingly well today, since because they were the most recent shorts produced, they feel the most “modern” to contemporary audiences.

Kicking off with an introduction from series host Leonard Maltin, Disc One features the majority of animated cartoon content. The shorts are presented either in chronological or alphabetical order, with an optional “play all” selection on hand that steps through in correct production order, which really is the best way to view these cartoons. Society Dog Show starts us off, and shows off why Disney was renowned for coming up with the best looking cartoons: apart from the crowds of people present in the short, it has such a good level of detail and added touches that it easily puts to shame some of the work carried out nowadays. Most exciting is the fire that breaks out at the dog show in which Mickey has entered Pluto. At first ridiculed by the other entrants, the Mouse’s pooch is declared a hero after saving a prize Pekinese, in an amazing sequence which is made all the more remarkable when one remembers that there was no CGI back then to do half of the work. There are nods to Buster Keaton, and a thrilling “ride” with Pluto on skates hints at the later perspective shots of Monstro in Pinocchio and even of the mine cart scenes in Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom! This was also the last time audiences actually saw Mickey with his big black eyed look: Freddie Moore’s redesign for Fantasia meant that, for the first time, Mickey would have “pupils” in his eyes, giving him a much more rounded and lifelike image. Though Fantasia – and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – were more than a year away, the new design was put to work immediately in the shorts, to see how it played to an audience.

The first film material to feature the new-look Mickey was The Pointer, a classic short that is still referenced in Disney output today. An Academy Award nominee (it lost to Walt’s own Silly Symphony remake of The Ugly Duckling), the short finds Mickey out in the woods with Pluto, attempting to make his pet a keen hunter. A famous encounter with a great bear ensues (“You know, er…Mickey Mouse?”), and the pair find themselves content to enjoy a can of beans as their supper. Again, tiny touches of “unnecessary” but totally appreciated detail are present, this time a 3D shaded effect on the characters. Eagle-eyed fans will also notice that it’s Mickey’s walk through the woods here that was recycled for the demonstration of perspective in one of Walt’s later television shows (also featured as a clip in the bonus section in this set).

Next up is 1940’s Tugboat Mickey, the first cartoon here to feature Donald and Goofy, and set on a small ship. Mickey often played support to these two in their joint films, but in this one each character is given roughly equal screen time, with Mickey facing up to a peculiar pelican, Goofy with a troublesome boiler, and Donald again battling the wonders of technology – this time the ship’s engine. It’s one of my favorite ever Mickeys. The pacing and quick cutting between the various situations in the climax, as the team attempt to rescue a supposedly sinking vessel, is stunning and again down to director Clyde Geronimi, who went on to direct Pinocchio and helms most of the early shorts in this set.

Leonard Maltin pops up again to introduce the next short, Pluto’s Dream House, which sees Mickey discovering a magic lamp and wishing for Pluto to have a state-of-the-art kennel built for him. Maltin explains that rather than have the film put away on the shelf, it should be seen in the context of its time. I guess the “slave of the lamp” connotations warrant such a disclaimer, and the lamp’s Atlanta-based accent is fairly thick, though the voice heard from the lamp is far from simply stereotypical of the time, since I didn’t find much difference between the sassy, hip and in-control character here and such “modern” equivalents as the talking car in the live-action Inspector Gadget movie, or even some of the smart-aleck vocals Whoopi Goldberg continues to use in her performances. Nevertheless, the short is fun, particularly when a radio broadcast chimes in and the lamp takes the narration as instructions for washing Pluto!

Mr Mouse Takes A Trip is the often seen film in which Mickey and Pluto have to dupe Pete the conductor when Mickey tries to smuggle Pluto onto a train. A harmless little short, and one in which Mr Mouse actually does take center stage, Maltin again provides a short disclaimer for the Indian disguise moment. The Little Whirlwind is next, bringing us into 1941, and a rare Mickey-only film in this set. With the promise of some cake from Minnie if he tidies up her garden, Mickey gets to work, though a playful whirlwind causes him some hassle which leads to a very dark forecast for Mickey! Featuring some great whirlwind effects, a snappy jazz score and a nod to Mickey’s earlier encounter with a tornado in The Band Concert, this one is a sweet little romp, and mostly notable for the debut of Ward Kimball’s short-lived experiment to give Mickey’s ears perspective.

Mickey and Minnie’s love affair is brought to the fore again in one of the most celebrated of the Mouse’s films, The Nifty Nineties, famous for its caricatures of Disney artists Ward Kimball and Fred Moore as a vaudeville double act. Although this information is given out elsewhere in the package, I did use to enjoy telling people this fact whenever the short came around when I was younger, and even though it was more of an in-joke then, I still get a kick out of the sequence. Set at the turn of the century, the short finds Mr and Ms Mouse out on a jaunty trip in their horseless carriage, to the strains of In The Good Old Summertime and is full of true sentiment for that bygone era throughout. Look out for other Disney names in the advertisements on display, an idea that was carried over to DisneyLand’s shop windows many years later.

The Orphan’s Benefit is a frame for frame remake of the 1934 cartoon featured in the first Mickey In Black And White set, making for an interesting comparison. Updates to the characters and the more refined technique of the animators are the only real changes here, and both cartoons are so similar that the same soundtrack has been utilized for both editions. Clara Cluck receives the least change to her character’s look, while Donald’s “Am I mortified!” Jimmy Durante impression has been toned back (he no longer sports the caricatured nose at this point). The Duck’s final shout of “Aw nuts!” from six years previous has been replaced as well, with his much more popular 1940s expression of “Oh phooey!” – but this is little more than a colorized version of a very funny and popular short.

Heading into 1942, and we have another remake, but one not so obvious. Mickey’s Birthday Party, draws from the 1931 cartoon The Birthday Party as well as the 1939 commercial film Mickey’s Surprise Party. As with elements lifted from these previous shorts, Mickey is surprised at Minnie’s place, the cooking goes awry, and the gift of a piano sets the scene for Mickey to show off his lightning dance moves. Unlike Orphan’s Benefit, this isn’t a completely recycled cartoon: additions to the cast mean that Goofy now has a supporting role as the cake baker, and Donald performs a dangerous looking tango with Clara Cluck. Symphony Hour keeps the music momentum going, and for sheer high-speed pacing, it’s hard to beat. After Goofy crushes the instruments Mickey’s orchestra will be playing in a live concert for radio broadcaster Mr Macaroni (a fun play on the Marconi system of the time), the musicians have to make the best of what they have! Employing extracts from a great number of varied musical pieces, the short is fast, furious and funny.

Already into the mid 40s, Mickey’s career was beginning to wane and his appearances were beginning to come few and far between, and it wasn’t until 1947 that Mickey returned to theater screens in a new short. Mickey’s Delayed Date redresses the balance a little, but is in fact a rather downbeat and non-eventful solo Mickey outing. One thing that is noticeable is the addition of crew credits, a result of the then-recent Studio strike. It seems Walt was mindful of not having his alter-ego up on screen for such a long time, as even if there are the usual splendid touches in Mickey’s Delayed Date, better was yet to come with the Mickey And The Beanstalk sequences from the feature Fun And Fancy Free (included in this set as a bonus), though it’s nice to see Mickey back to his usual rounded ear self by this time!

Mickey Down Under provided Mickey and Pluto with a new setting, but by this time it’s clear to see that the Mouse is again taking a back seat more and more to the dog’s antics. Even the main title music and Mickey’s whistle is the one usually reserved for Pluto’s output, and this was one of only two official Mickey shorts of 1948. The other was Mickey And The Seal, another sweet cartoon, and a step back up in style and quality from the previous two films in this collection. Here, Mickey accidentally brings home a baby seal in his picnic basket and Pluto tries to tell his master what has happened, to no avail until the seal pops up in Mickey’s bathtub. Although Mickey’s ears are more or less back in shape, his appearance has become the subject of the cruder, more simplified look of his 1950s TV output, which probably did nothing to help warm him to theater audiences of the time.

Pluto and his theme is predominant again in Plutopia and he even gets top billing – the title card reads “A Pluto Cartoon” – so doesn’t this short belong in a Pluto collection? Dragging Mickey into the 1950s, he does play more of a role here than in other straight Pluto cartoons of the time where he makes simple token appearances, though again this is a Pluto short in most ways. It is however, a really funny film, and one of the more inventive of the later outings, though Mickey doesn’t really look or sound like the loveable mouse we all know (ironically, he almost looks tired here). Making something of a last stab at greatness, R’coon Dawg is a grand return to form, both for Mickey, the writers and artists. Though Mickey again plays support to Pluto, the film reminds us of The Pointer, and has more warmth and heart than most of the post-Studio strike Mickey films.

Rounding out Disc One are Pluto’s Party and Mickey’s penultimate short subject appearance, Pluto’s Christmas Tree. Pluto must take a bath before Mickey will allow the local kids to come play at his birthday in Pluto’s Party, and needless to say, the miniature Mickeys that arrive do nothing but play rough with the pooch in a cartoon that feels a little rough itself. Unusually for Mickey, he seems more concerned that the kids are having fun rather than taking care of his faithful pup, even scolding Pluto at one point when it is the kids that are being spiteful. Pluto’s Christmas Tree remains one of the Studio’s most popular cartoons, mainly because of continued television showings year after year. It’s one of the best of these modern Mickey films (though again emphasis is on Pluto, this time chasing a tree-hidden Chip ‘n’ Dale), and one feels extra care and attention was given to it since it was intended to be a Christmas special. It has a specifically written score, a more detailed look, and even the title card is an animated affair, with snow effects that look as good as anything created in CGI.

Last but by no means least, and coming in 1953, The Simple Things finds Mickey and Pluto in relaxed mood, off for their final cartoon adventure. Out for a day’s fishing, a flock of seagulls try to steal their catch, with one in particular a sticky creature who won’t give up. Though a fun little cartoon, the formula was obviously beginning to wear thin, and Mickey and Pluto were finally “retired” (Mickey to his phenomenally successful TV show The Mickey Mouse Club), while Donald and Goofy continued the shorts for another few years. Changes in theatrical exhibition meant the end of character-themed shorts (for all the studios) and only a few featurette-length “Specials” were released each year.

Mickey would pop up only sporadically over the next 30 years or so, and then usually only in compilation features, such as Once Upon A Mouse. The most successful of these was Mickey Mouse Disco (1980), sadly not touched on here. Matching scenes from the vast catalog of Disney shorts, contemporary pop music was added to show the Disney gang dancing to the latest musical craze, an idea that later proved very popular on the Disney Channel’s series DTV, when hit songs by mainstream artists were given the same treatment. The film was based on a 1975 record album of the same name, and it was another record that also inspired Mickey’s eventual “comeback” to the silver screen proper.

Mickey’s Christmas Carol, based on the story by Charles Dickens, had already been adapted by the Disney staff for a 1974 album, though this film version differs in several ways. Utilizing Disney’s extraordinarily great cast of characters, Mickey’s Christmas Carol awards them “roles” in the story, largely based on their previously known personas. Thus, we have everyman Mickey as the much put upon Bob Cratchit, Jiminy Cricket as a kindly Ghost Of Christmas Past, Willie The Giant as the lumbering Ghost Of Christmas Present and an appropriate guest star as the dark Ghost Of Christmas Yet To Come. Putting in a naturally comedic appearance is Goofy as Jacob Marley, partner to the central figure of Ebenezer Scrooge, played by, who else, but Scrooge Mc Duck!

The short tries valiantly to regain the style and feel of the classic shorts, and largely succeeds thanks to the carefully observed writing and direction of Burny Mattinson. Though Mickey has the title, it really is Scrooge’s film, and this featurette marked the first time since the 1967 film Scrooge McDuck And Money that Carl Barks’ creation was brought to the screen (though he would go on to feature in the 1987 Sport Goofy featurette SoccerMania, and the popular Duck Tales TV show and feature spin-off). The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Short, the Studio’s first since Winnie The Pooh And Tigger Too in 1974. Apart from being immensely entertaining, its also an interesting film for fans as it marked the first time the older characters were handled by the new generation of Disney animators and a nice touch is that the Mickey “starburst” shot that opened each classic cartoon is resurrected here, but with Mickey in Cratchit’s guise.

Mickey’s Christmas Carol originally played on a double-bill with the 1983 re-issue of Disney’s The Rescuers. When it came time for the 1990 sequel The Rescuers Down Under to make it to theaters, the “tradition” was upheld and a new Mickey featurette, The Prince And The Pauper was featured in the theatrical program. In-between, Mickey had appeared in a small cameo role in Disney’s ode to the golden age of animation, 1988’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and Andreas Deja, who had animated Mickey in his scene with Bugs Bunny in that movie, was again brought on board to assist with Mickey’s performance here. After decades of playing supporting roles, Mickey is granted TWO pretty chunky parts to get his teeth into. The story is the Twain classic, retold as in Mickey’s Christmas Carol with the stock company as various characters. Though not as tight as Carol, the film reminds one more of Mickey And The Beanstalk’s approach.

Deja’s rendering of Mickey is wonderful, and Mr Mouse here gives perhaps one of his most in-depth performances (plaudits must go to vocalist Wayne Allwine as well, of course, who also provides a suitably English accent). He plays both the prince and pauper, switching places in traditional style so that the other can each live the life they don’t have. When the King passes away and its time to name a new king, Mickey knows he can’t keep up the deception and tries, with the help of pals Donald and Goofy, to bring the prince back to his rightful place. However, Captain of the guards Pete has other ideas, seeing himself as the new ruler, and not knowing anything about the two mice’s switcheroo. Mickey acquits himself well, the design (featuring a throwback to the Snow White/Sleeping Beauty storybook openings) is gorgeous, and the split-screen effects that allow Mickey to act opposite himself are seamless (wink, wink)!

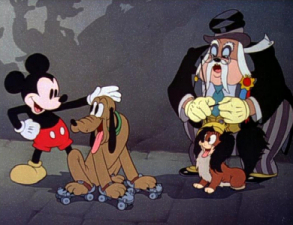

Completing Mickey’s theatrical filmography (the set quite rightly does not venture into video sequel or television territory) is the Oscar-nominated 1995 animated short Runaway Brain, a rarely seen, but brilliantly animated spoof of the old time Dark House features. It originally played with the “masterpiece” A Kid In King Arthur’s Court – hence why it remained rarely seen – although international audiences might have caught it with the same year’s A Goofy Movie, which makes much more sense and is where I first saw Runaway Brain. The short is very clever in the way it brings Mickey and Minnie up to date (he plays video games, she’s into skimpy outfits) but retains the wholesomeness of their traditional characters (they still look the same and act like teenagers in love). When Minnie mistakes Mickey’s offer of an afternoon of miniature golf for a luxury Hawaiian holiday, the in-need-of-cash Mouse offers his services to a Dr Frankenollie (great gag, geddit?), a mad scientist who proceeds to meld Mickey’s mind with Peg Leg Pete’s, turning Mickey into a ravenous monster! All works out well in the end, of course, though the final chase though the city is exhilarating, and the reference to Sigourney Weaver in Aliens never fails to get a big laugh.

Mickey’s short film career continues now on television, with the Mickey MouseWorks and House Of Mouse shows (some of which feature new shorts made by the traditional Feature Animation team), though Runaway Brain remains his final theatrical outing for now. It’s quite a way to go out, and most certainly with a bang rather than a whimper, and the short brings to mind the 1933 cartoon The Mad Doctor – another one of my favorites. Fans will finally be able to see this brilliant cartoon, and get a real kick from the in-jokes (apart from Kelsey Grammar’s Frankenollie, listen out for Mickey’s whistle and the name of Pete’s character among other things). Each of the three recent featurettes get an intro from Leonard Maltin, not really for any disclaimer problems, but to give a little general background info on the films.

Once again, the folks at Disney DVD have put together an outstanding package. True, the second disc is a little scarce, but the extended running time of two of the three featurettes does account for the space taken on the disc (Christmas Carol and Prince And The Pauper clock in at a combined 50 minutes). It is nice to have all the material in one place, though if we’re nit-picking, it would have been just as good to have included How To Ride A Horse on the Complete Goofy collection when that came out: the addition of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and Mickey And The Beanstalk especially smacks of filler. But this IS the one and only Mickey Mouse we’re talking about here, and it is simply a great collection of cartoons all the same – a highly recommended “must have”!

Is This Thing Loaded?

With Disc One pretty much packed with shorts, most of the extras fall in place on Disc Two, where Mickey’s most recent film appearances also reside. For those coming to all this on DVD for the first time, there’s a more than a fair amount to be getting on with, but for long-time collectors and LaserDisc owners, there’s a strong sense of déjà vu in store: most if not all of this material has been available elsewhere.

First up is an intro from Leonard Maltin, who places the collection in the context of Mickey’s career at that point. Getting to the Main Menu, the first extra is a “hidden” Easter Egg: locate Mickey’s cane for some rare footage from the recording sessions for Mr Mouse Takes A Trip. In this footage, previously seen on the Fun And Fancy Free LaserDisc release, we see Billy Bletcher and Walt himself performing as Pete and Mickey respectively. Though the film is actually silent, vocal tracks from the completed cartoon have been matched up to the visuals, providing a good sense of what it might have sounded like on the soundstage. Though the sound offers no variation on certain lines (the pair are seen reciting a number of readings, but only the final, film version is heard), it’s great to see Walt in the role (watch him react to Bletcher’s lines) and is a delightful reel of film, running eleven and a half minutes and sure to raise a smile.

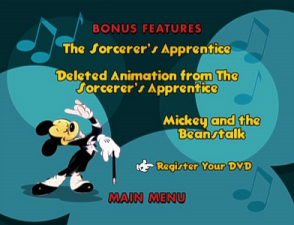

Presented as extras are sequences from a couple of full-length features: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice from Fantasia, and Mickey And The Beanstalk from Fun And Fancy Free. Rather disappointingly, these extracts have been lifted directly from the films themselves, meaning that they are not self contained inclusions (hence why they appear here as extras). Not so troublesome for the Fantasia clip (even though titles were produced for a stand-alone version which played in the late 40s and 1950s), since The Sorcerer’s Apprentice does open and close with fades, but note that Mickey meeting Stokowski at the end of the short is not present here. With the Beanstalk sequence, however, I found it a shame that the entirely self-contained featurette edition of this classic wasn’t picked (though that does provide a reason for long time LaserDisc fans to keep their version of that).

Originally the second half of the feature Fun And Fancy Free, that film had ventriloquist Edgar Bergen relating the Dumbo-esque story of Bongo the circus bear, and Mickey, Donald and Goofy’s take on Jack And The Beanstalk. The version shown here is literally the entire second half of that feature, complete with the Bergen live-action set up and interludes. A version of the story, in which Bergen and co were replaced with new animation featuring Ludwig Von Drake’s narration and bridging scenes, premiered on the Disney television show in 1963, and would have made a much more logical inclusion, for fans and collectors (who I imagine mostly already have the original Fancy Free film on disc). For all the shortcomings mentioned, the Mickey And The Beanstalk sequence looks like it’s benefited from a restoration makeover (and those who have read my review of the full feature will know how much I admire the beanstalk-growing sequence), while The Sorcerer’s Apprentice seems to have been taken from an older print, probably the original 50th anniversary clean up, and not the digital makeover the DVD received. Maltin intros both clips, which run a combined 45 minutes.

Maltin also pops up to introduce Deleted Animation From The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a before and after comparison of a more graphic scene in which Mickey’s chops up the brooms. The clip, lasting a minute twenty, is shown with original soundtrack matched up, as well as the final, more subtle “shadow” version. This is a little more filler, having been included on the Fantasia Anthology DVD set. In the bonus menu for Disc One, there’s one more hidden feature to be found: select the musical note above the listing for Mickey And The Beanstalk to catch an extra eight-minute promotional film presented to Standard Oil executives, to which Walt wanted to license Mickey and co to in an attempt to help them sell their product. As Maltin says in his intro, the first (black and white) half is the pure Disney sell, pushing Walt and his achievements unashamedly. But it actually works nicely as a nice recap of Disney’s career up until that point, topped off with a great two-minute color single shot of various characters parading by with reasons for Standard to sign up, which recalls the Parade Of The Nominees from 1932.

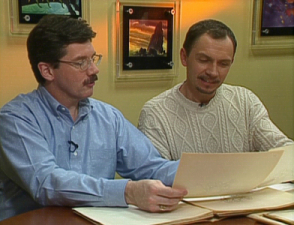

Disc Two’s extras delve more into Mickey’s later career. The Mickey’s Cartoon Comeback documentary talks to Mickey’s most recent animators, Mark Henn (Christmas Carol) and Andreas Deja (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Prince And The Pauper, Runaway Brain, Fantasia/2000). Lasting 16 minutes, the interview touches on how the two approach Mickey’s performances, as well as looking back on their favorite scenes. They also have some fun stories to tell, which I won’t spoil here, suffice to say that, as always with a Maltin interview, this is well worth checking out.

Next is The Voice Behind The Mouse, a chat with current Mickey and Minnie vocalists, husband and wife team Wayne Allwine and Russi Taylor, who have been performing since Mickey’s Christmas Carol in 1983. Again another sit down interview, the 24 minute piece covers all bases, with a discussion on what makes Mickey and Minnie work, previous voice Jimmy MacDonald, and some sweet conversation, though I couldn’t but help I’d seen some of this material somewhere before. The pre-restored clips from the shorts included do show off the amount of work that has been carried out on them, though.

Mouse Mania really is a rarity for collectors. Produced for Mickey’s 50th anniversary celebrations in 1978, the film is a weirdo-bizarro look at Mickey’s enduring popularity by stop-motion/pixelation animator Mike Jittlov, perhaps best known for his The Wizard Of Speed And Time feature. Absolute die-hard fans will have seen some of this footage before, but this is the first time that I know of that the entire two-minute clip has been made widely available. Set to music from the Electrical Parade at DisneyLand, the film is set in an analyst’s office, whose patient slowly begins to see the Mickey collectibles in the room come to life. Ever so slightly nightmarish, but fun all the same.

A trio of “cheats” feature next: Mickey Cartoon Physics from The Plausible Impossible and Mickey On The Camera Stand from Tricks Of Our Trade. Both titles will be familiar with those who have the Behind The Scenes At The Walt Disney Studios treasure tin, and long-time fans, who will have seen these clips on countless specials. Intros by Maltin point out that the entire shows are available on the other set, so I guess we’ll forgive them this self-promotion; the clips run a combined eight minutes. Mickey Meets The Maestro is the final lift, this time again from the Fantasia Anthology box set. In a 3:30-minute clip, producer Don Ernst explains the process through which Mickey was able to interact with conductor James Levine in the follow up film to the 1940 classic. While these clips haven’t been produced for this collection, they do touch on other areas of Mickey’s theatrical career and so are nice, not entirely redundant, inclusions.

Another rarity presented are the Color Titles from The Mickey Mouse Club (3:17m). Although Maltin explains that very few people have seen these, I have in fact glimpsed this material: it’s been used countless times before, especially in the video compilation specials of the 1980s. What’s great about them is that they mark Walt’s final recordings as Mickey, after he joked about performing as the mouse one last time. As is pointed out elsewhere in the set, Walt’s smoking and older age is indicated in Mickey’s not quite as falsetto and fairly shaky voice heard here, though that unmistakable Midwestern drawl comes shining through, and there’s fun to be had in picking out the visual references to past appearances and the many Disney songs used on the soundtrack!

The video-based extras wind up with the full-length uncut version of The Making Of Mickey’s Christmas Carol which, at 24 minutes, runs as long as the featurette itself! As with most of the 1980s Disney TV output, classic animation is used to set the scene (in this case Jiminy Cricket is charged with “producing” the film under budget) and cheesy synthesized music and video-effect graphics are used liberally. Though it may not be like the slick “making of” specials that we know today, that’s actually all for the good: we get a proper documentary here, with decent, uncut interviews with director Burny Mattinson, and very young looking animators Glen Keane and Mark Henn. Though dated, the doc shows the complete process of production, from storyboard to full color, even going back over Mickey’s history, a trip to the animation “morgue” (now known as the Disney Research Library), and chats with voice artists Clarence “Ducky” Nash (his last interview), Hal “Goofy” Smith and Alan “Scrooge” Young.

Rounding out the set are two still galleries: Publicity And Memorabilia and Story And Background Art. Around 95 images are featured across the two sections, ranging from original movie posters and advertisements of the time to production storyboards for The Little Whirlwind, Nifty Nineties, The Pointer and Symphony Hour. Leonard Maltin pops up every now and then to offer some audio-only comments on some of the pieces in question, which is enlightening, and the art is, as always, well worth searching through for some striking sketches.

All in all, this a good selection of extras that go some distance into Mickey’s later career and eventual comeback, and the fact that some are duplicates from previous releases should do nothing to deter one from picking up the collection. If one already has the majority of the featured archive footage in your collection, I would be tempted to knock off a mark or two from the overall bonus score, though for those coming to most of it for the first time, it certainly rates as a strong seven at least.

Case Study:

Keeping in the grand tradition of the film can-like embossed tins of the Walt Disney Treasures line, this new wave of titles maintains that approach. A two-disc keepcase is housed inside a metal tin, which also features a lithograph printing of a piece of related artwork (in this case Mickey as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice from Fantasia), and a booklet that outlines the set. New to this year’s design is a “Serialized Certificate Of Authenticity” which replaces the individually numbered tins, though the Disney Treasures branded logo on the front remains raised to the touch. The fact that Roy Disney’s signature remains intact on the packaging and card wraparound indicates that Disney’s reason for delaying these releases (to meet consumer demand) was true, and not for any internal wrangles going on in the name of Mickey at the Mouse House right now. Though the individually numbered tins themselves added a sense of exclusivity, this is a fine package nonetheless.

Ink And Paint:

As befitting Disney’s biggest star, all the stops have been pulled out for this release. Like all of the recent Disney Treasures, if you’ve seen any of the others in the series then you’ll know what to expect here: pristine transfers of some of the finest restored prints yet seen. True, the quality is perhaps not up to the stringent standards set by digital restorations of a Snow White or Fantasia, but these shorts are simply eye-popping, vibrant and detailed unlike any previous version I’ve ever seen. Perhaps one reason the films look so good is that I noticed that most of the prints are Buena Vista re-issues rather than the original RKO-distributed titles. Even for the purest of the purists this should mean little, since this only indicates the removal of the RKO logo – a small price to pay for later prints that look as good as these. Presented in their original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, the shorts on disc one look simply stunning, while disc two is even better: Mickey’s Christmas Carol, The Prince And The Pauper and Runaway Brain all come to disc presented in their original and correct aspect ratio of 1.66:1 – the first time any of these films have been presented in any home format in this way – and anamorphic transfers to boot!

Prints for the three later films vary: Christmas Carol shows its age, with a little bit of gate weave and grain, though the wider picture is a revelation. Similarly with The Prince And The Pauper, which matches its double-bill mate The Rescuers Down Under’s DVD for print quality (if you have that disc, you’ll find roughly the same here). Runaway Brain, despite being completed digitally, has been sourced from a film print here, but looks great, and much better than the pan-and-scan version that showed up on Japanese LaserDisc a few years ago. My one gripe with this was the soundtrack – it sounds fine, but is possibly a little out of sync, being a little early on the beats.

Scratch Tracks:

As with the picture, those who have any of the previous Disney tin sets will be familiar with the kind of sound quality presented here. Sounding just as they should, the shorts have a real stereo presence, although I am sure they are spacious mono tracks (early Disney stuff always sounded good). Hiss and any additional noise is kept to a minimum and it sounds as if some audio restoration has taken out some of the nastier glitches inherent in the original soundtracks. They all certainly match the visuals for clarity, while the three recent films sport decent stereo surround tracks. Music throughout, from the shorts to the featurettes, always comes through strong, meaty and fat, giving a great feeling of power behind these mixes, and they never sound too strained in the top ends. The only snag is the slight sync hiccup on Runaway Brain. English subtitles are also provided for the hard of hearing.

Final Cut:

Apart from Donald’s DVD debut, this is perhaps the most anticipated of this year’s four “wave three” Treasure releases, but there’s actually more interesting and historic material to be found on the couple of other releases (On The Front Lines and TomorrowLand). However, the shorts here look great – as always with Disney – and one can not deny that they handle their classic animation library with care (although not always with respect: see the continuing line of sequels to Walt’s classics).

Though I did find the extras on Disc Two to be somewhat padded out, the widescreen handling of the three most recent films is an absolute treat (with Runaway Brain’s sync the only slight anomaly) and well worth the price of admission alone. That they are teamed with some of Mickey’s most durable shorts from the classic era just simply is the icing on the cake. Now we only need a second black and white Mickey collection to complete the Mouse’s entire output (rumored for wave four), but in the meantime, this is another superb offering from Mr Maltin and the people at Disney DVD. In no fewer words, Mickey In Color 2 is an essential addition to any animation library, especially Disney aficionados – I can’t wait to see what else this wave of Treasures reveal and what the team come up with next!

| ||

|