Walt Disney Pictures (1928-1935), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (December 7 2004), 2 disc set, 334 mins plus supplements, 1.33:1 original full frame ratio, Dolby Digital Mono, Not Rated, Retail: $32.99

Storyboard:

Mickey Mouse’s complete filmography is concluded following a first collection of black and white shorts and two compendiums of his color adventures. With Mickey Mouse In Black And White Volume 2, all of Mr Mouse’s original theatrical cartoon appearances have now made it to the DVD format. This final set includes such rarities as The Barn Dance, The Plowboy, Mickey’s Choo Choo, The Jazz Fool, Jungle Rhythm, Trader Mickey, Mickey’s Pal Pluto, The Haunted House, The Moose Hunt, and Mickey’s Man Friday.

The Sweatbox Review:

2004 has been quite a 75th Anniversary year of up and downs for Mr Mickey Mouse. Not only is the company for which he is figurehead lulling in the box office doldrums but they have also recently forced him to headline an awful CGI video feature, the downright sad Twice Upon A Christmas (more No! No! No! than Ho! Ho! Ho!). Ironically, the very thing Mickey has stood for all these years – vibrant and quality animation – is currently one of the only things keeping the Disney ship afloat, with the home video releases of Brother Bear and Home On The Range bringing in the big bucks, though now even these types of feature are under threat from CGI eye-poppers such as The Incredibles (a case, if nothing else, of more animation filling the Studio’s coffers).

One bright spot has been Donovan Cook’s theatrically worthy, traditionally animated adventure The Three Musketeers, which saw Mickey, Donald, Goofy and the gang handled the way they were meant to be seen. And, now, here comes more proof that Mickey doesn’t need the supposedly trendy technology of today, with a second and final collection of shorts from his earliest incarnation. Heck, the Mouse doesn’t even need COLOR in order to be appealing and win over an audience!

Rather than picking up where the first volume – basically a port of an earlier LaserDisc release – left off, Disney’s pot-pourri cartoon selections means that this set plays as “sidepiece” companion to that first set. What is great this time around, is that, with all the more famous and requested shorts out of the way, this collection is able to center itself more satisfactorily on Mickey’s lesser known – and even rarer – appearances, most of them never before available on any home format. Indeed, those who pick this up and who already own the previous release, as well as the two Mickey In Color volumes, will then own the whole of the Mouse’s theatrical output!

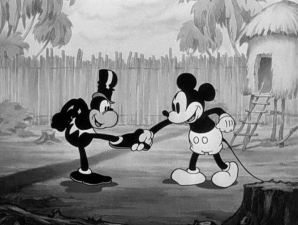

Starting off with Disc One (an apparently very good place to start!), the fun kicks off with The Barn Dance, completed in late 1928 but not released until March 1929. The shorts are playable in both alphabetical or chronological production order, as well as a handy Play All option that takes the chronological route. This first cartoon is a fairly routine Mickey picture, in which Peg Leg Pete (here without the peg leg) competes with Mickey to try and get the girl, Minnie (wearing her strange skirt and bra combo from her early days), at a dance. Now, you can call me a sissy all you like, but there’s really nothing like watching early Mickey and Minnie (voiced by Walt, of course, and the often forgotten Marcellite Garner) smooching, and their relationship is so real that it is one of the great joys of these early cartoons, though this being early Mickey means that he’s more boisterous with her than in later years!

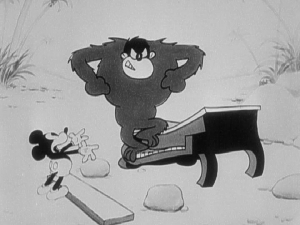

Mickey “puts on a show” and has problems with a makeshift orchestra for the first time in his career with The Opry House, also the first time he shows off his piano keyboard skills – to a humorous effect – and there’s even a suggestive “good riddance” moment made to an Oswald clone which could only have been sweet revenge for Walt! The piano’s back in When The Cat’s Away, one of the rare times Mickey appears the size of a real mouse (another would be in the 1934 MGM feature Hollywood Party, where he is chased and caught by Jimmy Durante). Mickey – and a whole cast of Mickey Mice – retains his small size in The Barnyard Battle, which almost runs as a precursor to such later films as The Brave Little Tailor, and is joined again by Minnie in The Plowboy, marking the debut of secondary co-stars Clarabelle Cow and Horace Horsecollar (here cheekily playing against Mickey).

Mickey’s Choo Choo has Mickey at the “wheel” of another anthropomorphic mode of transport, and reveals Walt’s early love of trains. Predating the likes of Casey Jr from Dumbo, Mickey handles himself well as the engineer of his out of control vehicle, in an excitingly animated (by Ub Iwerks) and detailed short. Since the synchronization of sound was still such a big draw to audiences back then, many cartoons played with their characters simply jamming with their musical instruments. As such, it’s back to Mr Mouse performing and showing off his abilities for the next pair of shorts, the often glimpsed The Jazz Fool and Jungle Rhythm; two revue films that otherwise don’t do much other than play on this public’s still-new taste for sound cartoons.

Minnie turns up in a swimsuit (though nothing as revealing as the one she bought in Chris Bailey’s 1995 homage Runaway Brain!) and needs a rescuing from lifeguard Mickey in Wild Waves, a mouse-sized edition of Baywatch! Just Mickey, the first of the cartoons to open with the famous “starburst” design, has the Mouse fiddlin’ around as a violinist (complete with fashionably ruffled hair), while The Barnyard Concert again predates a later cartoon, The Band Concert, when Mickey’s orchestra is continually interrupted in their attempt to play the classics. Jumping into his first “character part”, The Cactus Kid has “Don Mickey” rescuing senorita Minnie from Peg Leg Pedro, in a lively western adventure that features one or two gags Tex Avery would have been proud of, although The Shindig certainly finds everyone barnyard-bound again with yet another yard party.

Though he wouldn’t make his first named appearance until 1931’s The Moose Hunt, a Pluto-alike dog did appear in a couple of previous cartoons, including The Chain Gang (available in the first collection of black and white Mickey shorts and this same wave’s Complete Pluto set), and the next cartoon here, The Picnic, where the pup is referred to as Rover and is actually Minnie’s dog, though undoubtedly displaying the traits that would make him a star character in his own right, and no less playful! Traffic Troubles has Mickey behind the wheel of a crazy cab (Benny’s ancestor?), battling against the odds to get Minnie to her destination, with some more astounding animation. In The Castaway, Mickey gets stranded alone on a desert island, surrounded by standard Disney animal heavies of the time (a lion, a crocodile and in particular a stock gorilla, that would turn up here and there).

Before Mickey became such a huge cultural icon and established face of Disney, the little fellow had a lot more spirit – something that, due to public pressure to be more of a role model for kids, he slowly lost by his Sorcerer’s Apprentice turn in 1940’s Fantasia. The great thing about any black and white Mickey cartoon is that here is the real deal, presented just as Walt envisaged and before public conscience got the better of him. It’s a safe bet to say that a lot of Mickey’s earlier mischievous nature was more based on things a young Walt and his animators used to do (or wanted to do) when they were kids themselves. In Fishin’ Around, Mickey and Pluto try to sneak in some forbidden angling until a comedy police officer chases them off. Even though this IS early Mickey, the blatant disregard for authority is a surprising element, with such character behavior transferred more successfully to Donald Duck in later shorts.

The Beach Party (a typical “all the gang” picture) and The Barnyard Broadcast (Mickey puts on a radio show) are variations on already covered themes, and the disc comes to a close in 1932 with the cartoons The Mad Dog, which explores Mickey’s always close relationship with Pluto (and might have inspired events in later films as Snow White and Avery’s Wags To Riches), and Barnyard Olympics, a quite literally “animated” take on athletic competition that just shows how the animators were developing towards a broader scope. While it’s true that the big titles in Mickey’s early career were packed into the first volume, this set represents cartoons that often have not been seen by the public since their original release. And, so far, we’re only half way through, with even better to come!

Disc Two is split up into two sections. The cartoons continue, first of all, with another animal show, Musical Farmer, and the jungle-set Trader Mickey, a cartoon so typical of its kind, that Mickey is able to put off a (Pinto Colvig-voiced) cannibal tribe’s attempts to eat him and Pluto by getting them all tapping to a musical scene! Seemingly aware of Mickey’s lack of varied roles (and thus leading to his “safe” position of company figurehead), the next short, The Wayward Canary, gives Pluto a fair share of the spotlight, a trend that continues with Mickey’s Pal Pluto. The latter cartoon especially features Mickey in the way that would become a series trait, with the star of his own films relegated to set-up and pay-off appearances – almost only a co-star himself, worthy of these bookend sequences alone. These cartoons are fine, but it’s a shame to see Mickey sidelined so early on in his career, a fact only emphasized by the fact that, when Mickey’s Pal Pluto was later remade (as 1941’s Academy Award-winning Lend A Paw) it was designated as a solo Pluto cartoon in that character’s series.

Mickey’s Mechanical Man pits the Mouse’s not-so-Iron-Giant robot invention against a boxing opponent (there’s that gorilla again!) in one of the disc’s exquisite highlights, though it’s the return of Pluto to center stage in Playful Pluto. This is the one that truly defined the pup’s character, with the spectacularly animated scene of Pluto stuck to a sheet of flypaper one of Pluto’s all time highlights, and a masterpiece of personality animation, drawn by Norm “Fergy” Ferguson, which sparked the possibility of Pluto having his own series.

In Mickey’s Steam Roller, our star plays second fiddle again, though this time to his own “nephews”, who appeared as supporting kid roles in a number of shorts from this period before Donald was plagued by Huey, Dewey and Louie. By this time, the Silly Symphonies were exclusively being released in full Technicolor, and though Mickey’s popularity outweighed any audience desire to see him in this way, it was only a matter of time until Mickey made the switch. However, Mickey Plays Papa, with its Mickey-impressions of Hollywood comedians of the time, absolutely deserves to have been shot in black and white, and really would only ever work this way, being a total product of its era: a “snapshot” of the big names and filmic styles on the then Hollywood landscape (Chaplin, Durante and the Universal Old Dark House pictures). It places Mickey back in the limelight for a change, and is a very sweet and funny cartoon to boot!

By 1935, all Disney product was being released in color prints, and Mickey himself had starred as conductor in a bright red uniform in the musical short The Band Concert earlier that year. A couple of months later, the final black and white Mouse cartoon, Mickey’s Kangaroo, arrived in theaters. A pretty routine, Pluto-led story, this one has a boxing ’roo from the outback turn up on Mickey’s doorstep, and is chiefly memorable for Mickey’s spat with the Australian newcomer.

Through he pops up at the beginning of the set to introduce the cartoons, Disney Studio historian and Treasures host Leonard Maltin remains out of the picture for the most part. There are, however, a number of cartoons that have been deemed a little more “sensitive” for various factors, and these have been placed in their own section (the “split” mentioned above), titled From The Vault, with Maltin on hand to give some historic information in a special introduction, which plays whenever the Vault option is selected. Here you’ll find a further ten shorts, ranging from 1929 to 1935, all complete and uncut, though containing what could be considered “hot potato” elements.

After Maltin’s “look how far we’ve come” talk relating to attitudes towards race and social behavior, first up is The Haunted House, a cartoon of spooky proportions that plays like the Skeleton Dance-meets-The Mad Doctor. The short has never been rated PG, as The Mad Doctor was in 16mm re-issues, but this could mainly be down to the fact that it has only very rarely been seen since its original release. In the short, Mickey comes across an old house during a particularly frightful storm, only to end up playing organist (against his will) for a collective of ghosts, who dance their merry souls out.

The Moose Hunt features Pluto, named for the very first time, and seen as his “official” debut, even though it re-uses scenes from the earlier Minnie/Rover short The Picnic. Another rarely seen cartoon, this one only usually gets a passing reference in histories on the Studio’s characters, though is distinctive not just for the introduction of Mickey’s canine companion, but also for the fact that this was the first – and last – time Pluto ever spoke! After this film, it was decided that, although Mickey and the gang were humanized animals, Pluto would behave as a real dog: from then on he only ever barked communication, and another gag, where Pluto flaps his ears and flies, was never used again.

The Delivery Boy finds everyone back in the backyard for this musical short, which takes a sudden change of direction when Peg Leg Pete’s dynamite ends up being mistaken for a toy by Pluto, ending the occasion with a bang! The Grocery Boy has Pluto’s appetite getting the better of him and a furious pursuit ensues when Mickey chases him for running off with Minnie’s turkey dinner. It’s Mickey to the rescue again in Mickey In Arabia, when Minnie is captured by a crazy sheik, which features all manner of predictable stereotypes, though it is an extravagant looking short. Then, Mickey “sells” Pluto to a wealthy family in Mickey’s Good Deed in order to raise money for the poor. Pluto’s penchant for turkey is raised again, when he comes running back to the Mouse, with dinner in tow!

We’ve all heard of the reasons why similar films from Warners and MGM haven’t been issued on disc, but did you know that Disney also produced a cartoon spoof of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Mickey’s Mellerdrammer is that film; an amazingly intricate cartoon that puts turns the famously controversial novel into a stage-bound adaptation for the gang. The show doesn’t manage to make it all the way through, however, when the production is halted by a rampaging pack of bloodhounds! The Steeple Chase (here shown with a reconstructed title card and music from much later in the Disney shorts history) is another Mickey-centered cartoon, and a lot of fun. When his horse gets drunk, Mr Mouse dresses up two stable boys in a stage costume and enters the race anyway. More through luck than by skill, the trio win, though Mickey’s cheat is close to being revealed a number of times!

Shanghaied is another Mickey-to-Minnie’s rescue picture, with the villain again played by Peg Leg Pete. The twist this time is that the short starts off with the mice already captive! It’s a fun duelling picture, and quite the adventure, not really belonging sliced off from the other adventures for anything more that one very brief “blackface” gag. Finally, Mickey’s Man Friday is, like The Castaway, loosely based on the Robinson Crusoe story. In a repeat of earlier escapades, Mickey is chased by cannibals, but an alliance with a friendly native saves his tail. Though it contains stereotypes common in the Hollywood films of the age, this short does contain a thoroughly enjoyable battle chase, and was Mickey’s last black and white release before the all-Technicolor The Band Concert.

Though my outlines above may render some of the cartoons as sounding very alike, being either “let’s put on a show” barnyard musicals or cannibal-chasing adventures, there is actually a lot of variety in these films. True that the audience was still coming up to speed with synchronized sound, and Mickey’s great popularity eventually made him a weaker character, but it’s an absolute treat to be able to finally see some of his more guarded shorts and complete the evolution of the character. The wit and invention on display is simply awe-inspiring, with never a moment going by that doesn’t have some gag or technical embellishment to the already painstaking detail raising a chuckle or a surprised eyebrow. In a way, these shorts are the best barometer to gauging how much the Disney cartoon had come on in such few years, and the direction they were headed. For those with any of the other sets in this series, this is a must, and for either animation aficionados first timers, the wow factor of what was achieved in these cartoons is nothing short of amazing.

Is This Thing Loaded?

As usual with the Disney Treasures, the main content filler are the cartoons themselves, though space has been set aside for some interesting additions. They layout of the menus will be familiar to anyone who has gone through any of the series, with classy, art deco designs which place the discs in their time period, and suggest a passing reverent nod to Walt himself, with none of the forced previews that we get on Disney’s more “commercial” releases.

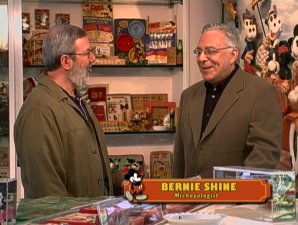

On Disc One, as well as an introduction from host Leonard Maltin, we’re offered Mickey Mania: Collecting Mickey Merchandise, an exceptionally entertaining look at the collection of one Bernie Shine, a “Mickeyologist” who has some wonderful items to show off, as well as an affectionate poem tribute to Mickey and the gang. Speaking to Maltin, Shine discusses his affinity for early Mickey collectibles, and the relationship that merchandising genius Kay Kamen had for licensing the Disney figures and turning them into a brand unto itself. The 13-minute piece never flags, with the two men chatting amiably about the collection, aided with plentiful photographic illustrations and a snappy edit style. Don’t miss the 1935 store display that predates the Disney Store window dressings by well over 50 years!

Mickey’s Portrait Artist: John Hench throws the spotlight on to an often overlooked contributor to the Disney legacy, who in the last couple of years has come out from the shadow of the legendary Nine Old Men to be recognized in his own right. Here, in an interview clip conducted about a year before his recent passing away, he speaks to Leonard Maltin about his philosophy behind making Mickey a “real” person in the many anniversary portraits he created for the Studio. Full screen images are shown, as well as Mickey’s original model sheet, and the almost five-minute clip makes a very nice addition to the set, and sweet tribute to Hench.

Disc Two also contains a special feature or two of its own, as well as the From The Vault cartoons, which could be seen as extras themselves. A Gallery section highlights 22 Background Paintings, 136 Animation Drawings (a variety of story sketches from untitled shorts), Mickey’s Poster Archive (a selection of 17 images), and 38 stills featuring book and Mickey Mouse Magazine covers, records and sheet music, collected as Mickey Mouse: Fully Covered.

The Mickey’s Sunday Funnies: A “Virtual” Comic Strip is presented in two options. Picking the Video version will lead into some highly peppy background information on Floyd Gottfredson and the original Mickey strip, an example of which, Mickey And Rumplewatt The Giant, plays out afterward with individual panels flashing by at a readable pace and accompanied by music. The other choice is the Still Frame edition, which offers each panel in its own, full screen blow up. A lovely idea that I haven’t seen presented on disc since the Pinocchio LaserDisc from the early 1990s, the video version runs, with the introduction, to a respectable 15 minutes. I found no additional “Easter Egg” features.

It must be getting harder and harder to wow fans with rare footage and new featurettes for the series, especially since so much of it has shown up in other sets and the legends that created these films are sadly passing away sooner than they should, or already no longer with us. However, Leonard Maltin and his crew (DVD credits are not forthcoming, but quite possibly the work of the always excellent long-time supplemental material producing team of Kurtti-Pellerin) have assembled a neat collection of extras here, which should please without overbalancing the main attraction’s content.

Case Study:

Well, now, here’s where we must start being tough on the new wave of Disney Treasures. It’s understandable that due to Roy Disney’s resignation from the company, the new tins should not feature his signature on any of the packaging, but this has extended to the new titles not having ANY sort of cardboard wraparound at all. This not only gives the feeling of an “incomplete” set, but also looks a little bare design-wise, and ultimate means that they sit on a shelf with no indication of their titles on the side, looking out of whack with the previous entries in the series.

Added to this is the fact that the set’s contents, usually printed directly on to the back of the tins, is now represented on cardboard slips, which have been gummed on and come off all too easily. In fact, one of mine slipped off while I was removing the shrink-wrap. I’m in two minds on whether to glue them permanently to the tins, but for now I have tucked it away inside for safekeeping.

Changes initiated last wave also remain: instead of numbered tins, we get the certificates as before. This time around, Roy’s name has been removed and only Leonard Maltin’s signature is in place. I have no real problem with them doing this, but the lack of series consistency is annoying, especially on a serious collectors’ package like this, and how hard would it have been to design a new wraparound, for Peg Leg Pete’s sake?

On the plus side, the discs now come on double-sized white keepcases similar to the Vault Disney line, with the usual booklet and lithographed artwork reproduction inside. It’s the quality of the films that counts, but the nice thing about the tins was that they always felt special. With these cutbacks, the new wave looks a little too “standard”, and even the “D” in the Walt Disney Treasures signature logo didn’t look fully embossed to me (though this is supposedly a common occurrence and has happened with previous releases, depending on when they were printed).

Functional, and still nicer than a lot of packages out there, but not quite up to the standard we expect and know from Disney with these releases as usual.

Ink And Paint:

The video and audio aspects of any release like this are going to be based on what shape the original materials are in, how well they have been preserved, and how they were originally recorded. Let’s not forget that these cartoons, although produced in a Hollywood Studio environment, are still among the earliest made that survive complete and intact today. All cartoons on Disc One are presented slightly windowboxed, in their original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, the first time they have been seen in their true screen dimensions, according to an on screen announcement.

The shorts on Disc Two are full-frame 1.33:1, with some reconstructed title cards. One complaint levelled at the first volume was the electronic reconstructions for titles that had been lost, though here they are handled much more transparently, with a still frame hold in places where opening sequences might have otherwise been unusable. The quality here is exceptional, and apart from some expected inherent grain and cel defects, the later cartoons looking speckle clean. An amazingly sharp image!

Scratch Tracks:

As with the image, the soundtrack is based on how well the original elements stand up to the stringent standards of today. Thankfully, the Disney Studio was always very careful to catalog and preserve their library, meaning that decent sources were available to clean up for this release (a couple of the cartoons are missing their title card cues, which is acknowledged in an on screen announcement that notes these have been lost). The result is startling for films of this age, especially when one considers that sound itself was still a new medium. In fact, the most background hiss I could pick out as being something of a surprise was on the Walt Disney Treasures logo itself, with its synthesized intro music sounding as if a projector was whirring away in the background! Other sounds, primarily Maltin’s comments, are reproduced very cleanly – top marks for recording and the cartoon restorations.

Final Cut:

For anyone with the first Mickey In Black And White collection, this is an essential purchase, if only to finish up the Mouse’s early career. I’d also recommend the two Color volumes for Mickey’s complete filmography, though the films contained in this particular offering are possibly the most interesting as they are more sought after, from a collector’s point of view. A classic character, rendered in classic animation the way he should be, this edition goes along way to making up for any recent CGI upheaval in the Mouse’s career and, with the second volume of color cartoons released earlier this year, is the only way to truly celebrate Mickey’s 75th. Happy birthday, Mr Mouse!

| ||

|