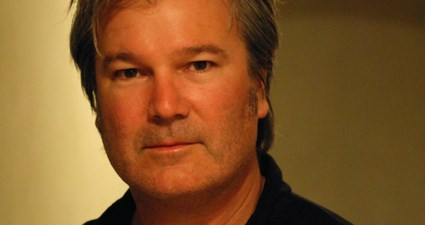

As a multi-talented director, Gore Verbinski’s cinematic success has crossed multiple genres and collected more than $3.5 billion at the box office.

During his teenage years, Verbinski juggled between music and movies for his artistic passion. In 1979, Verbinski helmed his first “franchise”, a series of Super-8mm films called The Driver Files, which he financed by selling his guitar. However, he could not shake his love of music, playing in several Los Angeles-based rock bands such as Thelonius Monster, Daredevils, Bulldozer, The Drivers, The Cylon Boys Choir and The Little Kings.

In 1987, Verbinski graduated from the prestigious University of California, Los Angeles, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. His first professional directing gigs allowed him to blend his love of the audio and visual media, directing music videos for alternative bands like Bad Religion, L7, NOFX, 24-7 Spyz and Monster Magnet.

Verbinski soon turned to television commercials, creating spots for Nike, Coca-Cola, Canon, Skittles and United Airlines. He received widespread critical acclaim for the original Budweiser Frogs ad, in which three amphibians rhythmically croaked the popular brand name. Premiering during Super Bowl XXIX in 1995, the ad launched a popular catchphrase as well as a recognizable mascot in the team of frog triplets. For directing the iconic spot, Verbinski won four Clio Awards and one Cannes Advertising Silver Lion.

In 1996, Verbinski directed the stylish half-hour short film The Ritual, which garnered enough acclaim to catch the attention of execs at DreamWorks Pictures. The following year, he released his feature directorial debut, Mouse Hunt, a zany comedy about two brothers who inherit a house already occupied by one pint-size tenant. The movie was well-received enough for the studio to put Verbinski in charge of its Brad Pitt and Julia Roberts vehicle The Mexican (2001) and horror remake The Ring (2002). Verbinski also stepped in for director Simon Wells on The Time Machine (2002), taking over the last 18 days of shooting after Wells left the project due to exhaustion.

Verbinski’s next film would be the one to propel him to mega-success and kickstart a multi-billion-dollar franchise. Disney hired the director to helm Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, based on the company’s popular theme park attraction. Working with Verbinski, actor Johnny Depp developed the perfect accent, costume and personality to create the iconic character Captain Jack Sparrow. As Walt Disney Pictures’ first PG-13 film, Pirates became an international success, collecting $654 million and five Oscar nominations.

Disney quickly hired Verbinski to film back-to-back Pirates sequels, Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End. In July 2006, Dead Man’s Chest entered domestic theaters, achieving the largest opening and single-day gross with $55.8 million. It also claimed the biggest opening weekend gross with $135.6 million, becoming the first film to make $100 million in two days. Ultimately, Dead Man’s Chest grossed $1.07 billion worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing film of the year, the third film to hit $1 billion at the box office, and Disney’s highest-grossing film of all time. It also claimed an Oscar for the groundbreaking visual effects that turned actor Bill Nighy into the villainous Davy Jones. As for At World’s End, the second Pirates sequel nabbed a worldwide total of $963.4 million, becoming the highest-grossing film of 2007 internationally.

Meanwhile, a story idea which Verbinski had conceived when doing the first Pirates flick lingered in his mind. It was the tale of one neurotic chameleon, stranded in the Mojave Desert, who finds himself while pretending to be the new sheriff of a town called Dirt. Verbinski pitched the story to George Lucas’ visual effects studio, Industrial Light and Magic, which loved the idea. Soon, work began on ILM’s first animated feature, Rango. For the film, Verbinski re-teamed with trustworthy Pirates pals Depp and Nighy as well as composer Hans Zimmer. As with At World’s End, he also stretched his musical abilities, contributing to the film’s score.

On March 4, 2011, Rango opened in theaters to rave reviews. Critics praised Verbinski’s direction as well as the stunning visual design and intelligent dialogue. By the end of its theatrical run, Rango had collected more than $245 million worldwide.

Now, with awards season in full swing, Rango has been named the best animated movie of 2011 by numerous critics associations and has found itself nominated as Best Animated Feature at the Annie Awards and the Golden Globes. With these and further accolades in view, some awards pundits believe Rango could very well be the frontrunner for the Best Animated Feature Oscar.

Nonetheless, Verbinski remains grounded in his expectations for the film. Currently, he is making rounds among online journalists, recalling the making and the meaning behind Rango, which is where we find him today…

Animated Views: How did you get the idea for Rango?

Gore Verbinski: Well, I’d thought about doing an animated movie for quite some time. I’ve always been a fan. After doing a tremendous amount of computer-generated animation on the first three Pirates films, I just felt like it was time to take what we had learned and try to go for a completely-animated film. I had been working on a pitch since about 2003. Just the basic core idea of doing a western with creatures of the desert that had evolved. I was talking to Johnny about it.

I just became exhausted coming off those [Pirates] movies, but I felt like I wanted to commit to this three-and-a-half year endeavor.

AV: From what I understand, you developed this idea with illustrator David Shannon.

GV: David Shannon, John Carls and I had breakfast once, and we came up with the basic premise. Years later, I brought the outline to John Logan, and he committed to help us write it. Then I hired Dave Shannon, Crash McCreery, Jim Byrkit and an illustrator named Eugene Yelchin to basically design all the characters in the film. David Shannon is a children’s book author. Crash McCreery designed Davy Jones and all the creatures in the Pirates movies. Jim Byrkit was my storyboard artist for years, and Eugene Yelchin is a fine-artist painter.

Ultimately, it became an 18-month story reel but very low-tech. We had a necessity. We created a new model for an animated movie. We wanted to do a traditional story, but we wanted to reduce our overhead so we just worked out of the house, cooking hotdogs and barbecue. We were working for about a year-and-a-half – drawing, putting it all into a Mac computer, getting a microphone, doing all the voices, creating. Basically all the creative decisions were made at that point. We then recorded the actors live all together for 20 days. Then “phase three” was another 18 months of ILM executing that plan but not with a tremendous amount of iteration, because it was really the visual effects model at that point.

So half the movie was the traditional animation approach, and half the movie was more about how we would execute the shots.

AV: Rango is the first animated feature from Industrial Light and Magic. Did that add any pressure for you?

GV: Well, I didn’t know anybody else. I didn’t know where else to go, where we’ve done thousands of shots together. And ILM, to me, isn’t a big cement box. You go into a place like that, where there’s thousands of employees, and it’s casting; you’ve handpicked your team. And I wouldn’t have known where else to go. You work with the people you’ve made mistakes with in the past – and overcome those mistakes and learned from them – and it was kind of nice. Nobody on the movie had made an animated movie before, so we kept it that way.

AV: Rango is a reunion for you, also, in that you got to work with Johnny Depp, Bill Nighy and Hans Zimmer again.

GV: Johnny jumped on it very early. It comes out in one word, which is “trust”. I said, “I’m taking a few years off and doing this animated movie. It’s a western with this lizard suffering an identity crisis”. And he just went, “I’m in! Let’s do that. That sounds great!” He didn’t even read the script or anything; he sort of committed based on faith. We couldn’t have raised the money to make the movie without that commitment.

I got to work with a fantastic cast, with Ned Beatty, Harry Dean Stanton and all my heroes. And Bill just really committed when it came down to a kind of Grim Reaper assassin character. I couldn’t get Jack Palance, so I got Bill Nighy to do his best impersonation. [laughs]

AV: One thing I found surprising was, in a time when pretty much any animated film is released in 3D, Rango wasn’t. What led to that decision?

GV: 3D was neither here nor there for me. I didn’t want to take our limited resources and apply it to 3D. I said, “Look, I’m going to make the movie for this budget with a plan to execute that, and it’s going to be 2D. If you guys want a 3D version, then that costs more”. We did some tests early on, which looked incredibly beautiful. We started production, and – I think midway through – Alice in Wonderland came out in 3D. People started running numbers and saying, “Hey, well, maybe this should be 3D”. But at that point, it was just cost-prohibitive, because we were so fully down the road on our shoot to 2D. Ultimately, we sat and looked at the 3D test, and we looked at the 2D version, and we said, “You know, we’re really not missing anything”. I didn’t feel it was missing a dimension when looking at the movie.

AV: Instead of using performance-capture technology, you filmed the actors acting out their scenes and then used that as a reference for the animators. How did you get that idea?

GV: It just comes from live-action. I’m not a traditional animation director. It was basically based on fear. You don’t want to abandon techniques you’ve used before. I really enjoy having actors together in the room and seeing them react. In a process when nothing happens in real time, that’s the one opportunity for you to have an intuitive reaction to something occurring. I think “occurring” was the big operative word. In any discussion on the film, we just tried to say, “Let’s make it feel like there’s a tortoise talking to a lizard. The cameraman is there, and he’s got the camera on his shoulder, and he’s trying to capture this thing that’s occurring”.

It may go wrong. The actor may do something unexpected, and you’re going to have to adapt. The focus puller might be a little late, and the shock might buzz. All of these sort of anomalies you get when you shoot live-action, I think, add up to a sense that something unpredictable might happen. The live-action record was our only opportunity to react intuitively to something immediately. Everything else was very frontal lobe and very concise and planned out. The computer lends itself to perfection by default. You sort of have to manufacture these anomalies.

We encouraged open line overlaps and people acting exhausted running around and moving around. We had props, wearing a cowboy hat while walking in our street clothes and doing this theater of the absurd. But it was all about trying to get a lively feeling to the audio record, and then really trying to protect that through the iteration process and not kill it. I think my biggest fear was that things would become clinical.

AV: A lot of folks love the references to Hunter S. Thompson. Where did those come from?

GV: You have to realize the story reel in those first 18 months in that house. We were taking long walks and drawing stuff on the computer. It was a bouillabaisse of ideas being thrown around.

I think the whole story started as, “Okay, it’s a Western. Creatures of the desert. And he’s “the man with no name,” an outsider who comes in this town. What if he’s a lizard? Yeah, he’s a lizard. Maybe he should be aquatic because he’s a “fish out of water.” If he’s aquatic, maybe he’s a chameleon. What if he’s an actor? He’s an actor – and he’s got issues. Okay, he’s got issues.” Out of that came this whole notion that, “Well, maybe he can break the fourth wall. Maybe he’s aware he’s entering the genre. Maybe then we can comment on other films because that’s how he sees it. He sees this, “Oh, I see I’m in a Western now. I’ll pretend to be this guy.”

We arrived at all that sort of organically. Then we were talking one day about Rango being on the side of the road. Somebody said, “Wouldn’t it be great if the red Cadillac from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas drove by?” “No, no, even better, let’s have him hit the windshield! And then Johnny could see Johnny – these two characters he has played could come face-to-face with each other!” We just started riffing, and stuff like that came.

AV: Speaking of references, there’s a scene in which the characters are underground, and they walk past a huge eye. Some people say that was a nod toward director Hayao Miyazaki. Any truth there?

GV: That’s really interesting. It’s not a direct nod. I think it’s something we chose not to explain. But I do think that there is a spirit in his films that we’re all huge fans of and inspired by, which is that anything can happen. There is a sort of dream logic to his films. I certainly was inspired by that when we were doing Jack Sparrow in Davy Jones’ Locker and his hellish trip talking to himself.

I think Miyazaki is very liberating as a storyteller, for all of us. So it’s not a literal reference, but I think it’s more of an inspirational nod. You can do things that don’t have to have a rhyme or reason to be. They have the logic of dreams.

AV: Of any movie this year, my favorite scene is Rango’s encounter with the Spirit of the West. Timothy Olyphant did such a great job. But I’m curious, was Clint Eastwood ever approached to voice that role?

GV: No, it was always intended to be a parody. So we didn’t want to go there. I was just walking by the television one day, and I heard Timothy’s voice – I forget what it was, a TV show or something. I just sort of doubled back and looked through the door and was like, “That’s our guy. That’s our voice. That’s our Spirit of the West.”

AV: Where did you get the idea to make Clint Eastwood represent the Spirit of the West?

GV: I think it came out of conversations early on with John Logan. If Rango was an Elvis fan, he’d be visited by the spirit of Elvis Presley, in his lowest point of internal turmoil. It just seemed like Rango was a guy looking for a hero, while trying to be a hero, and his ultimate hero was going to advise him.

The whole metaphor of crossing the road and what lies beyond it – and ultimately his catharsis, resurrection and return to the town – they’re all Western sort of mythologies, even Joseph Campbell mythologies. You spend 18 months with seven guys in a house, barbecuing, walking, talking and drawing, there’s no intention other than trying to form the narrative.

AV: Do you know if Clint Eastwood has seen that scene?

GV: I don’t know, but I’m hiding. [laughs]

AV: Many people view Rango as the frontrunner for Best Animated Feature at the Oscars. Any thoughts there?

GV: I think there are a lot of great movies this year. It’s an honor if we even get considered. We just tried to do something different. Animation is not a genre; it’s a technique for telling a story. There’s lots of great animation out there. I just think we’re not trying to chase what other people do so well; we’re trying to step off the path a little bit, and fumble to see what maybe we can do over here, just a little left of center. It’s nice when people recognize that you’re trying something different.

AV: What’s next for Rango? Have you already thought about a sequel or even a TV series?

GV: I don’t know. It’s just like, suddenly, we’ve spent three-and-a-half years on Rango; we’d like to spend three-and-a-half years doing something completely different, rather than more of the same. I think it’s okay that sometimes everything doesn’t have to be a sequel.

I’m sure there’s a financial model for it. But creatively I feel like we all want to try to spend three-and-a-half years trying to do something we’re not sure of, rather than repeating something we sort of would know how to do.

AV: Rango is a family film, of course, but the themes are deep and appeal to all ages. Could you summarize some of those themes? Critics have suggested everything from existentialism to even biblical themes.

GV: I think the big uniting theme is that everybody wants to be loved. I think Rango is just trying too hard. It’s a classic “great pretender” story. But pretending to be a hero is one thing. When people start believing in you, things change, and there are responsibilities to his audience who are really his friends. He’s moved from inanimate objects to real flesh-and-blood friendships, with people who count on one another.

There are a lot of more heady themes in the film. But I think, ultimately, we keep coming back to that simple one, which is that the guy just wants to fit in.

Rango is now available to own on DVD and Blu-ray.

Our deepest thanks to Gore Verbinski and Julie Tustin at Paramount.