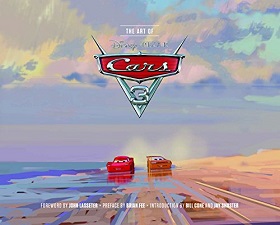

In Disney-Pixar’s Cars 3, the legendary Lightning McQueen is blindsided by a new generation of blazing-fast racers and is suddenly pushed out of the sport he loves. In order to get back in the game, he will need to accept help from an eager young race technician with her own plan to win, as well as inspiration from the late great Hudson Hornet. Cars 3 puts Lightning to the test as he sets out to prove to everyone that #95 isn’t through yet.

In Disney-Pixar’s Cars 3, the legendary Lightning McQueen is blindsided by a new generation of blazing-fast racers and is suddenly pushed out of the sport he loves. In order to get back in the game, he will need to accept help from an eager young race technician with her own plan to win, as well as inspiration from the late great Hudson Hornet. Cars 3 puts Lightning to the test as he sets out to prove to everyone that #95 isn’t through yet.

To get behind-the-scenes of one of the summer’s most anticipated films, we met with Production Designer Bill Cone, who was instrumental in giving Cars 3 its visual identity and soul.

Bill is no stranger to the universe of Cars. He began his time at Pixar as a freelancer on Toy Story, which led to positions as a production designer on A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2 and Cars, as well as the short films Air Mater, Time Travel Mater and La Luna.

Lightning’s new adventure, in different parts of the world, was for him another occasion to capitalize on his expertise and passion for nature and outdoor painting.

Animated Views: On Cars 3, you were Production Designer, along with Jay Shuster. Can you tell me about your collaboration?

Bill Cone: We kind of divided up the pie, in a way. He was more responsible for the character design and development, and my job was more like the world, the nature of the world and some of the light and color of the film.

AV: As you had been Production Designer on Cars, what was your attitude regarding the original movie’s visual vocabulary in the new film?

BC: There’s a few ways I can think of. First, we went somewhere else in the world; we didn’t just stay in Radiator Springs. A fair amount of the film takes place in the south-eastern part of the United States. So, we had to go there, research that, find a language for that and establish it as a unique place in the world that doesn’t look like anything else, so that it has its own identity. In addition, we used a seasonal fact: we were there in the winter. We went to the Daytona 500 in Florida in February 2015 and then we explored parts of the countryside in North Georgia and North Carolina and South Carolina. There was actually snow and bare trees: a true winter landscape in that part of the world, especially up in the mountains of Georgia. So, we incorporated the idea of winter into the film because it also suited the emotional content of the film. That was a second difference. And then the third one was: we tried to sort of evolve the idea of the metaphorical use of cars and automobile forms in landscape. We call it “carification”. You can see it very much around Radiator Springs. So, we looked at that again and tried to evolve it a bit and give a slightly different twist.

AV: What do you specifically remember from that research trip?

BC: A group of us – the director, the head of story, the producer, Jay Schuster and I – all went down to Florida for the Daytona 500. We were there for about three days and the day after the big race, Jay and I flew up to Atlanta, Georgia, and then we rented a car. We tried to rent a hot rod, a car that would look like McQueen. So, we rented a Chevrolet Camaro. We wanted a red one but they only had a white one. Then, when we started driving, like the very next day, it snowed. So, we had a white car in a snowy landscape, which was kind of funny! We just drove up to the mountains and we went to this area, a town called Dawsonville, Georgia, one of the birth places of NASCAR, the North American stock car racing association. They would make alcohol in the mountains and then illegally move it down to the city and sell alcohol that way. The mechanics and the drivers for those vehicles that were smuggling alcohol were the best race car mechanics and drivers at the beginning of automobile racing in America in the late 40s – early 50s! That’s why we went to that region, because it was one of the origin points of that type of racing. We also went to an old dirt track up there, and then drove through the land and looked to a lot of different buildings. We ended up in North Carolina and we went to some contemporary technical places like wind tunnels for cars and a race car manufacturing facility. So, we just kind of get an idea of how the landscape felt and looked, and what the buildings were like. We also met a lot of interesting people.

AV: Judging by your personal work, your tastes naturally lead you to outdoor painting, and pastel coloring. How did you translate that in Cars 3?

BC: I was inspired by Ralph Eggleston’s work. He was the Art Director on Toy Story. He did a lot of pastel work on that film – lighting studies. It gave me a huge respect for his work, but also the desire to try it because I thought it was a very rapid medium and the expression of light and color was very powerful in that medium as well. So, I started doing that around 1996. I really wanted to do lighting studies for A Bug’s Life and, in order to get better, I went outside to practice at lunchtime and on the way to work. I’d be driving between my house and the office of Pixar, and I would pull over and paint in the morning and then in the evening. After a while, I realized that I was learning a lot from nature and that began to really affect my thinking about light for film. So, I wanted to use ideas I got from nature in the movies themselves. On Cars, we attempted that to a fair amount. Now, it’s been over 20 years since I started painting outside. I’m very much kind of a student of nature, and I still incorporate that type of thinking into all these film projects that I work on, including Cars 3. So, it’s just an ongoing study of nature and of the most meaningful qualities of natural light that can be then applied in such a way that they have an emotional impact on the narrative.

AV: How do you balance pastel and computer in your work?

BC:That’s a good question. Outside, I’m very used to pastel. It’d be as if I played a musical instrument I was very comfortable with. So, in painting outside, I’m very comfortable with that medium. I think in the types of movies we make I use the computer to paint more often these days just because of the ability to edit the image or change it according to what the director might want or things like that. I don’t use pastels as much. I think I would in development again if I had the opportunity but it’s harder to do in a production these days.

AV: Did you want to make a connection between McQueen’s emotional state at some point, and the landscapes he discovers?

BC: In a sense, the primary connection there would just be the circumstance. He has evolved as an individual. He’s basically aged and his career has reached a point where there’s younger people, younger cars that are faster than he is. He’s not winning, and then he has a horrible accident. So, he’s in the position of any mid-career or late-career racer who has an injury and then has to make a comeback in his own profession. And it’s a struggle for him. We felt that the landscape that we encountered had this slightly, sort of poetically bleak aspect through the bare trees and these kind of soft rolling hills. It was kind of moody. We put fog in there; the sun is not always shining. Those qualities of light, and the weather and the season seemed to work in conjunction with the circumstances of McQueen. His journey is also spiritual, in a way.

AV: Indeed, the light, and the textures seem pretty different from the previous movies.

BC: I believe the tools that we have nowadays are more sophisticated. There’s a greater -some might call it ‘realism’ but we call it ‘believability’: the ability to create a rich texture of elements. It could be weeds, vegetation, concrete or peeling paint, things that make a place feel like it’s been there for a long, long time. The level of complexity that we can achieve, or a subtlety with shadows or how light is reflected into shadow – it’s far greater than it used to be. In some ways, it’s almost a default of the tool nowadays because we try to avoid making things look like it was done in a computer. It’s part of our job!

BC: The technical side has enormously changed over time. People who work on the technical end of the process are far more artistically oriented than they used to be. Before, it was very much code-based scientists-type people that had built these tools for the computer but they hadn’t really necessarily thought about film as a medium or the artistic relationship of colors, forms and things like that. Now, many of the technical people are very artistic and so, it’s a much easier collaboration.

AV: Do you consider the job of the Production Designer more of a solitary work, alone at his desk, or as a team work?

BC: It’s actually both. That’s really a question of where you are in the evolution of the production of the film. At the beginning of the film, there are very few people. You might have the director, the head of story and the producer and then one or two production designers. It’s a very small crew. You have a direct contact with the director, you read film treatments or the early scripts and you start developing ideas. There may be only one or two artists directly involved at that point and you have more time to do research or gather evidence or ideas and develop them. You’re engaged with a few people but there is a lot of more solitary work, more thinking and maybe turning out drawings and paintings. Later on, when you’re going into production, you need an enormous amount of assistance to get it done. So, you bring on more people and then you have to function as a larger team and you’re delegating at that point: you need to give other people jobs – design those characters, design these sets. Initially, you come up with ideas about where they are, what they look like, what the scope is and what it all means. And then these people are the architects, to some degree, of those places. So, you work with a much larger crew. And then, the irony also is that you have to go to a lot more meetings all the time. So, there is no more time or very little time left to sit in your office and just paint.

AV: As you participated in so many Pixar films that made animation history, what does Cars 3 represent to you?

BC: To me, it’s just an evolution, in a sense. We practice our craft. On every film, we get to try out ideas and see them to their birth. Then they go into the film, and then the film is done. Each time, it may be a three- to five-year journey where you explore a set of ideas and push them all the way through that process to the final result. I just feel like each one is a different degree in college, like I keep going back to the university and get another degree. Doing a movie is like going back to school, practically.

With very special thanks to Bill Cone and Chris Wiggum at Pixar, and to April Whitney at Chronicle Books. Bill Cone’s concept art comes from Chronicle’s The Art of Cars 3.