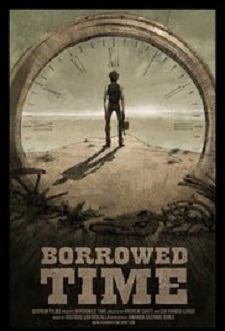

Borrowed Time is not just a song by John Lennon. It is also the title of a one-of-a-kind short imagined by Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj, which seduced the Pixar University staff enough to support them in their directorial debuts.

Borrowed Time is not just a song by John Lennon. It is also the title of a one-of-a-kind short imagined by Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj, which seduced the Pixar University staff enough to support them in their directorial debuts.

“A weathered Sheriff returns to the remains of an accident he has spent a lifetime trying to forget. With each step forward, the memories come flooding back. Faced with his mistake once again, he must find the strength to carry on.” — This is the story they wanted to bring to screen.

Born in Peru of Colombian and Scottish parents, Andrew Coats grew up around the world before settling in the U.S. at the age of 16. Meanwhile, Lou Hamou-Lhadj’s childhood took root in the culturally rich suburbs of exotic southern New Jersey. Despite their disparate upbringings, their shared passions for fine arts and film led both Andrew and Lou to study Film at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. It was here that they first met, and learned they could combine those passions into the most rewarding of art forms: animation. Kindred spirits in their love for bringing things to life one frame at a time, they both worked on each other’s shorts during school, and vowed to someday make a film together when the time was right.

Lou enjoyed the next 8 years at Pixar as a Character Artist on WALL•E, Toy Story 3, Partly Cloudy, Day & Night, Brave, Toy Story That Time Forgot, and The Good Dinosaur. For the first 3 years, he and Andrew stayed in close contact while Andrew rose through the ranks at Blue Sky Studios, animating on Horton Hears A Who, Ice Age: Dawn Of The Dinosaurs, and finally serving as a Character Lead on Rio. Andrew then joined Pixar in 2010 where he has animated on Cars 2, Brave, Toy Story OF Terror!, Inside Out and The Good Dinosaur. Reuniting at Pixar rekindled the spark to create something together. During their spare time over the past 5 years they have been learning, growing, failing, picking each other up and ultimately crafting Borrowed Time, a very moving and insightful movie, about which we wanted to know more…

AnimatedViews: How did you choose “western” as the context of your film?

Andrew Coats: Back in 2007, we had brainstormed a few ideas for a short we’d like to make, and one of them happened to be a western. We grew up watching films like Sergio Leone’s “Man With No Name” trilogy and really loved the iconography: from characters and setting all the way through interesting framing of shots and editing that is specific to the genre. However, at the time, I was at Blue Sky, and Lou was at Pixar, and though we gave it our best effort, making a film across the country without today’s technology really wasn’t feasible. So, we decided to hold off on making a film until we were in the same place. It wasn’t until 2010, when I started at Pixar, that we could finally move forward with something.

Lou Hamou-Lhadj: By that point, we had both been working in the industry for a while, and had the privilege to contribute to a number of great family films. But we knew that to make this film we’d have to work in our off-time, and that fueled us to spend that time making something “different”.

AC: We were a bit frustrated with the lack of breadth in stories told through animation in America, and wanted to contribute to the medium by helping illustrate that it isn’t merely a children’s film genre, as much of the public perceives it. We wanted to champion American animation as a medium to tell any story.

LHL: What better way to do that than to target something uniquely American? Westerns are irrefutably a genre, the way that horror is a genre. You can make an animated western, or an animated horror film, and if you’re true to that, suddenly the “animation as a genre” argument falls away. It’s just the vessel we use to bring that story to life. That said, westerns are ripe with opportunity.

AC: That iconography I mentioned brings with it certain expectations. We may choose to frame a shot of someone you believe to be a hardened and weathered cowboy, and in the same shot, reverse that expectation and have him break down with emotion. Fighting for that unexpectedness is really at the core of why we chose to make a western, and specifically in the medium of animation.

AV: What came first? The context or the theme of the movie – forgiveness, second chance.

LHL: Context, but only for a short time. In the very beginning, the story was very different from what we ended up with. It was a typical train heist with a reversal at the end. We were inspired by some of the fun action-oriented shorts produced at Gobelins when we were students. They’re fantastic, and their strengths are largely in the art and craft of animation. But after writing an outline of a film that felt like that, we decided that although it would be fun to do, it was a surface-level short that didn’t have much emotional impact. What became important to us at this time was to learn how to tell a more emotionally compelling story.

AC: We knew we had a lot to learn; we spent the better part of the next two years trying to tackle a story of forgiveness, that was based on an experience of betrayal I had gone through in my life around the time we were writing. That story had another main character and was way more complicated to tell, so after trying for over a year to crack it, we learned that it was not possible to get to a satisfying resolution to the many relationships in the 6 minutes we wanted the short to be.

LHL: We almost lost hope at this point, for a moment we decided to cut the film down to a teaser that revolved around the inciting incident on the cliff.

AC: At least that way we would have something to show for all the work we had put in… but luckily, cutting the trailer showed us a new angle on how to tell a much simpler story.

LHL: The ultimate incarnation was framing that formative moment for him – the cliff scene – with him returning to the scene many years later, and letting his physical and emotional journey through that space fill in the gaps for us of who he’s become. He’s looking for closure, instead of forgiveness, but it feels like there’s a lot of subtext and history behind it, because there is! That process of subtraction and simplification is what we really embraced to get us to the final version of Borrowed Time.

AV: In that regard, your film is very metaphoric. Can you tell me about that aspect?

AC: It is, and a big part of that is that is very difficult to get an audience to deeply empathize with a character in 6 minutes. Metaphor can provide life outside of the time watching the film. It challenges the audience to reflect on the meaning. We also personally enjoy films that leave an impression on you and challenge you to be introspective, instead of spoon feeding everything. The difficulty, of course, is riding that line without being too ambiguous and losing the audience.

LHL: One of the many challenges with a project that spans as many years and versions as “Borrowed Time”, is that you weave those metaphors in different ways for each incarnation of the film. Since the film is so visual, tweaking the presentation of an object or moment can greatly impact its meaning, not only for the audience, but for the characters as well. We had to be particularly careful of this, because it’s easy to get too heady, or have remnants of old metaphors and appropriations persist that are no longer supported, or no longer mean anything to the character. The pocket watch was an example of this. Late in the game we realized we had been a little too intellectual about its importance, and had to make some adjustments to sequences that were already far along in order to have it carry any emotional weight for the characters.

AV: How did you come to choose that subject, and what does it represent to you as artists?

LHL: It evolved quite a bit, but we both have had experiences in our lives where we attach a certain level of sentimentality to a common object. Be it a touchstone to remember someone by, or a reminder of deep regret. Ultimately those objects can serve as a source of catharsis, as they represent a moment, a memory, or a piece of that person. I even sometimes struggle with the fear of losing people who are not yet gone, and by extension, losing an item that I’ve imbued with a connection to someone. It’s maybe a little crazy, but it’s deeply human, and we’ve seen that in the response to the film as well. The multitude of ways in which it has touched people’s lives is totally unexpected, but is a reminder that loss is a universal experience.

AC: Truth be told, the suicidal overtones were something we resisted for a long time, because as an artist you want to be sincere in your work, and that’s something we’ve never experienced. It’s weird though, how a film or a character can take on a life of its own after a while, and it is your job as a writer to listen to and empathize with their motivations, and be truthful to that, because in the end they’re not you at all. For our protagonist, it was a desire to reunite and reconnect with his father that took him to that cliff edge. It was a positive feeling, so the idea of suicide was no longer this taboo notion we feared we couldn’t relate to. The realization that this story has brought some comfort to those who can see themselves in it is humbling. It’s about as much as you can hope for, as a filmmaker, or artist in general.

AV: This is about time, too. How did you approach that notion through animation?

LHL: In a variety of ways, really, ultimately it was that teaser edit that provided us an opportunity to frame time in a different way. We wanted every bit of detritus in the wreckage to be a painful harbinger of what had happened; he’s just trying to power through the pain to get to the release at the edge of that cliff. The intercutting allowed us some economy, but tied the specificity of what we showed to what he was going through in present day. His reaction to these things plays in stark contrast to the relief when one of those bits of debris brings him what he needed all along.

AC: Everything is treated in a way that reflects that time is a force of nature. Things are shaded to be worn and weathered and caked in dirt, the character’s pained shuffle of a walk and scar on his cheek call back to having fallen off of the carriage as a boy. The watch is a little closer to the cliff edge from where we left it in the flashback, as rain and erosion have carried it off a bit. But perhaps most important is the portrayal of this character being stuck, frozen in a moment in time emotionally. Speaking to visual metaphor, we show him ensconced in the watch as we fade back to present day to drive that home…with subtlety.

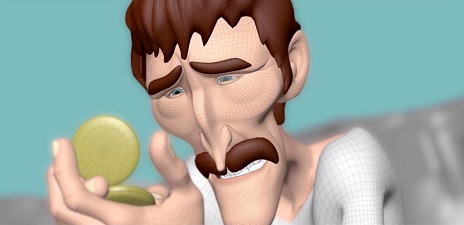

AV: Can you, as Character designer, tell me about the design of your characters?

AC: We love drawing and sculpture and at one point were even entertaining animating this film in 2D. Design is all about pushing for qualities in someone and externalizing them. Our early designs for the main character evoked elements of Lee Van Cleef, and Daniel Day Lewis. Some people even say that he looks a little like my dad.

LHL: His design originally was intended for an unassuming deputy that was a mastermind behind a train heist, but that same design, with little modification, served as a gaunt, haunted individual who grew to be a shell of a man.

AC: We very much chose to make him feel skeletal, even in the lighting of some shots. His iconic facial features, such as his nose, longer face and piercing blue eyes, were purposeful as we needed the audience to recognize them in his younger incarnation by just cutting between the two. The challenge was creating a youthful and appealing naivety within these strong features, and reversing the toil and guilt that we feel in his older design.

LHL: His father, the sheriff, is supposed to be the embodiment of authority. Still, we wanted him to be loving, and warm in his own way, so we looked to actors like John Wayne and Bernard Hill to give us that quality in design. The sheriff’s clothing too, is something that his son, in later years, dresses in reverence to. It’s that idea of not quite being able to fill the shoes that were left behind.

AC: Lou and I ping-ponged the designs, always pushing for specificity, but a lot of the evolution happened in storyboarding the film over and over. From there, we both shared the modeling of them as well, and that iterative process just took form in 3D.

AV: How did the presentation of your project to Pixar University go? To you, what made Pixar want to accompany you in your project?

LHL: Pixar University’s Co-op program is really in place as an educational outlet. Employees are encouraged to try out a variety of roles in the filmmaking process and grow in their understanding of what it takes to make something like “Borrowed Time”. The result is that a lot of people are exposed to things they’ve never had the opportunity to do before, and it feeds back into the studio in a really enriching way.

AC: The process of presenting it, however, it really one of clearing it with our Legal department. So long as the film’s conceit isn’t encroaching on something that is in development, you’re cleared to make it however you can, provided it doesn’t disrupt the existing productions. Our film was the first CG production to be completed under the Co-op. Prior to “Borrowed Time” the program was mostly supporting live-action films.

AV: What are the most important things about animation you learned during your journey?

AC: Animation is inherently a long, meticulous and controlled process. You can’t leverage actors playing off of each other, or shoot extra coverage to find the story in edit. There is no such thing as spontaneity: everything has to be planned to a tee. So, your really have to try and focus on what you love and enjoy about it, and remember that at the end of the day, the reason we animate is to tell stories and connect with people. And for me that extends past just connecting with an audience. Filmmaking is a collaborative process that involves multiple people from various crafts and places in their lives. If you get to know people that are working with you and what their goals are and help foster them, it will make for a richer experience for everyone and ultimately a better film.

LHL: Speaking to Andrew’s point, you really can’t get there on your own. In school, we were solely responsible for everything in our films, and while that’s an environment that makes sense when you’re just learning the basics, there’s as much, if not more, to learn from working with a team. We didn’t start this project that way – we began with chasing that sense of ownership we missed from our earlier films. The moment we put that hubris aside and began to delegate and really invest our trust in others, the whole process flourished. Building that team and sharing our journey with our friends was one of the absolute best parts of this experience for us.

AV: How did you come to choose Gustavo Santaolalla as your composer? What did you want him to bring to your film?

LHL: We were playing The Last Of Us as we were trying to crack the story of Borrowed Time and fell in love with Gustavo’s music. He has a natural ability to create a soundscape that has space and depth, with as much emphasis on silence and the space between notes.

AC: That was a perfect fit with our “less is more” vision for the music in our short. We wanted to give space for the audience to live in emotional moments and be there with the character, instead of leading them and forcing them to feel something with the music. The music should be there to support the way the audience feels, not force it.

LHL: Working with Gustavo was such a pleasure. He is a true collaborator who listened to our thoughts intently and surpassed and challenged our expectations of what music could bring to the film.

AV: Andrew and Lou, how do you think you complement each other in the whole process?

LHL: Terribly. We’re the worst match for each other.

AC: Every day was a living hell and just kept getting worse with time! But seriously, we are lucky that we found each other in school and not only respected each other’s drive, but also enjoyed working together. Our tastes and skills overlap quite a bit, as you can imagine, but our strengths and focuses in filmmaking aren’t identical. We tend to let each other take the helm on different aspects of the film, all the while talking through what the end goal is.

LHL: That might be our biggest strength together: we listen to each other from a place of mutual respect. We argue and differ in opinion all the time, but we usually end up in a place that is better than where we started. It’s definitely an iron sharpens iron situation.

AC: But yeah, he’s the worst.

LHL: DITTO.

AV: What are your projects, now?

AC: We are currently still working our day jobs at Pixar, but have some ideas that we are exploring for next projects.

LHL: The reality is that our focus has been on getting Borrowed Time through the festival circuit. It has been a lot more work than we could have ever anticipated, and there’s still a great deal to learn about.

AC: In our careers, we have gotten used to doing our work and finishing on a film and just moving on to the next one, while a separate machine of PR takes the film and gets it out to the public. For our own film, we have to suddenly be that machine (with the bulk of the work done by our amazing producer, Amanda Jones). We are definitely out of our comfort zone to say the least!

LHL: Needless to say, it’ll be refreshing when we can refocus on being creative!

Be sure to watch the Borrowed Time trailer and making-of here.