There are moments in life when you have the feeling that history is being made; and when it’s someone like Glen Keane who is involved in a project, you are pretty sure it is history of art that has been made.

There are moments in life when you have the feeling that history is being made; and when it’s someone like Glen Keane who is involved in a project, you are pretty sure it is history of art that has been made.

After working for 38 years at Disney, Glen Keane decided to leave Burbank to launch his own studio and pursue further artistic exploration with more personal projects. As such, he’s now collaborating with Google’s research division, called ATAP, doing in a new context what he does best: giving spirit and soul to hand-drawn characters and stories.

His first creation with this group is entitled Duet. The animated short blends world-class artistry with innovative rendering and interaction technology for mobile to create a new canvas for the next generation of storytelling. Duet tells the story of Mia and Tosh and how their individual paths in life weave together to create an inspired duet. The unique, interactive nature of the story allows the viewer to seamlessly follow the journey of either of the two characters from birth to adulthood.

We were blessed to be able to talk with the master about this incredible project, which may be considered a true breakthrough for the art of animation.

AnimatedViews: It is often said that, in animation, there’s the idea or the story first, and then is created the technology to turn it into reality. Here, with Duet, it seems that it was technology first. Can you tell me how technology inspired that wonderful story?

Glen Keane: I thought about that a lot.

When I first went up to Silicon Valley and met Regina Dugan who was the head of this group called ATAP, a research division for Google, she showed me the technology— the little phone that was more of a window into a virtual world than a screen, and at the same time the largest screen you could imagine because you would look into infinity there, and everything was possible. She said, “What would you do with this?” I knew that it was going to be about drawing for me, because that’s where all the ideas come for me. I went away with the challenge to push myself creatively somehow, and to do something beautiful and emotional, which was what Regina asked.

I never would have come up with this story without technology. Just like Michelangelo with the Sistine Chapel, for certain creative ideas, I think it’s really important to know what the limitations of technology are or to understand that you are not limited in the way that you used to be limited. Typically, when I would animate, say, Ariel singing her song and she swims off-screen, she never stopped swimming to me. I was just forced to stop drawing her, but she continued to move in my mind. In my imagination, there are not cuts. The characters just live, they are. When I started to develop this idea for Duet, my first realization was: the characters are always living, they never stop existing on the screen. They’re always present, very much like I always imagine when I animate, but I just never got to experience that. So, right from the beginning, it was a very comfortable skin to step into and feel that natural flow of the animation.

So, I came up to Lake Arrowhead where we have a house. For about three weeks, I approached the story from a very traditional way. I don’t know why I did that. The force of habit, I guess, after 40 years at Disney doing things in terms of the story arc, the conflict of the character, the development, the first act, second act, third act, all the story structure points put up on storyboards.

Developing the story immediately posed problems because one of the things about traditional filmmaking vocabulary is that you can stop a shot at any point just by a cut. In this case, I had to figure out how the other character would be continuing to move around while this character would move the opposite way. Also, I always knew that they were going to grow older at the same time. The whole idea of the evolution of following two characters whose lives will cross paths was made possible because of the technology that allows you to actually turn in “360” dimension. I had been thinking for a long time about stories of destiny, and characters whose lives cross one another. I’ve always wanted to do that. I just never imagined that in such a clear, physical, technological kind of a way.

By the end of three weeks, I was just so frustrated because I didn’t like anything I had. It didn’t feel real for me. I was wondering maybe I had nothing here to do. I didn’t know what to do. I called my son, Max, who became the Production Designer for the show, and I told him how I was feeling; and he said, “Well, Dad, when was the last time you just animated just for the joy of animating.” And I said, “A long time. It’s been at least 10 or 12 years.” He answered, “Why don’t you just forget about Google and everybody else and animate just for the joy of it. I’d love to see what that does.”

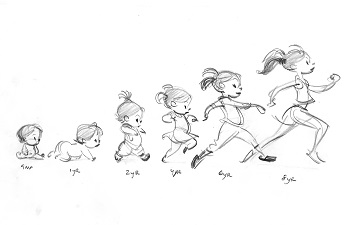

You know, it’s funny how sometimes you need permission to do what you know in your heart. I also talked to Gennie Rim, who became my producer. She always said, “Glen, you should just use your superpower— drawing”. So, I just started to animate and I knew right from the beginning it would start with a baby. So I started animating a little baby crawling, then standing up, and I filmed my granddaughter doing a skipping action, a combination of a walk, a skip and a hop, but motivated by joy. I realized I had something wonderful here and immediately I knew that the story was going to be about these two characters crossing. Then I called Max and Gennie to come up to Lake Arrowhead where we spent three days working on this. And surprisingly, it just flowed naturally out of that encouragement to animate something that was just locked away in my heart, which I needed to actually start drawing to discover what it was. Because the technology was so new, I had no idea how to use it, and I actually needed to just dive into the water and start.

AV: It’s interesting how state-of-the-art technology pushed you to get back to the roots of your art, to the very reasons why you animate.

GK: It is very true. This path was already hidden inside of me. I just didn’t know what it was. There’s that poem that I love by the American poet Longfellow. He describes the feelings that we had. He says, “Feeling is deep and still; and the word that floats on the surface / Is as the tossing buoy, that betrays where the anchor is hidden.” It’s not just the joy that’s hidden. It’s human life. It’s a theme that I think is pretty much true in all my work: we are all created in the image of God, and designed to express a certain path, a joy in life. That kind of comes through in Ariel or The Beast, all those characters that have this burning desire inside of them to become something that seems impossible. And I love the idea that, here, these two characters have separate paths, but as they cross, they actually help one another become who they’re meant to be. That’s something that’s always been inside of me, and I think I just needed to start to draw to release that.

As a matter of fact, after I started to animate, and Max and Gennie were there looking at that beginning part, when the cells are forming and turn into this baby, I realized I had already animated that! I remembered then that two years before, one night, I was at home and I just had this desire to animate a baby floating in space, almost like Michelangelo’s figures floating and turning there. It was midnight and my wife came into my studio asking me what I was doing, and why I was doing that. And I had no idea. I just needed to do it. And now that’s the actual animation that we used in the beginning of Duet…

AV: In terms of synthesis of hand-drawn and CG animation, how would you compare the process between Duet and Paperman, which you took part in?

GK: While I was making Tangled, John Kars was supervising the animation along with myself, and both he and I had talked quite a bit about this synthesis between hand-drawn and CG. For us, it would be wonderful if there was a marriage between the two. So, when he started Paperman, I did the first little animation test along with Patrick Osborne. I animated the scene first in pencil, and then Patrick used the rig and model that we had designed and stretched it and pushed it so it’d fit the drawing. Then I went back in on top of that. I did some more drawing and it was ultimately a back and forth that we did. That was a very natural collaboration between hand-drawn and CG. So, it was animated first, then CG, and then they used hand-drawn lines around the edges to give Paperman that look.

But, to me, the ultimate goal is to have the computer doing what it does best and hand-drawn doing what it does best. In the case of Duet, I felt like it was a really natural balance between those two. What the virtual world was creating was dimension and space, and I had to animate in a way that made you believe that, no matter where you turned, those drawings were existing in space. And we did that by placing animation on a Maya card, and moving it so that wherever you turned, it would be there in position as if you could never have missed that character. It was a very natural three-dimensional world, and it reminded me of when I was a child and I would draw, I wouldn’t draw just to do a flat drawing on a piece of paper. I would draw to make the paper go away and step into a dimensional world. That was my experience with Duet. There’s a truly deep, dimensional world and I had no limits. I could go as high up or deep down or in space, or far to the right, or far to the left or diagonally. There were no limits. Even though I was animating on paper, with a limit, I knew that the screen had no limits.

That was the challenge: how to create the illusion that there are no limits. I believe that’s the fun of an art form. Because it creates an illusion. One of the things that I feel is, in some ways with computer animation, because everything is built in the computer as a dimension, the idea of the fun of illusion is lost and your imagination becomes lazy. Whereas with hand-drawn, there’s something that’s constantly asking something of the viewer. On Paperman, the three-dimensional form was king and the line was serving that. In Duet, the dominant force is line. The color was added in a very delicate, simple way so it never held the power of the line. We were celebrating line with the entire animation.

AV: How do you see the role of the viewer in Duet? An additional director, or an additional character?

GK: I don’t see the viewer as a character or as a director. I see them as an audience, but in a much more intimate way. Much more like sitting around a campfire telling a story to someone that you have direct eye contact with. My granddaughter is five years old and she keeps asking me to tell her a scary story, and I tell her that someday we’re doing a campfire and I’ll tell her a scary story around that campfire. Because scary stories are meant to be told around a campfire. Because they’re so engaging. They really need that eye contact. That’s something very intimate, very personal. There’s no distance between you and the story.

So, when I was working on Duet, I was very conscious of that eye contact with the viewers during the whole experience. I knew where they were, and I sensed when I might loose them. For curiosity, they might turn away and wonder what’s happening with the other character. That’s a very intimate reaction. When we recently released Duet on Moto X phones, we were immediately getting emails from people who received the animation as a gift, and at about three o’clock in the morning, we got a message from one couple who’ve been wanting to have a baby, and she was not able to get pregnant. They watched Duet and saw it as a sign. So, she took a pregnancy test, and sure enough it was positive. So, they sent us an email thanking us that somehow through Duet they were being blessed with a baby! That was one of many messages that showed us how personal and intimate it was to viewers. It is so unlike the limited experience of a movie theater.

AV: That new kind of storytelling is not without impact on the conception of the musical score, too.

GK: Scot Stafford already composed the score of the first Spotlight Stories, Windy Day and Buggy Night. So, he already had an experience with that kind of storytelling, because it’s very difficult to imagine a score that has to be a servant to the viewer changing direction at any time. Particularly with Duet where there’s two scores going on. There’s her score, and his, which is simpler but slightly different. Even the dog has his own theme. The way we did first was thinking of it as one, unique story, as we follow the story along the path of Mia. Mia’s being for me the dominant story. So, we decided to just follow her all the way and build all the moments emotionally so that when they’re in the tree there’s this magic kind of moment that’s happening and then all the way to when she’s dancing, building and building and building to this very romantic moment. That’s where I felt I needed the support of Scot’s music to be able to animate the characters.

So, first, we had this very linear line. Then Scot had to go back and create sections of music that he described as armadillo scales. He would create pieces of music that you could actually hear and that could be stretched out longer or become very short, like a spring, depending on how much time you would play on them, according to the choices you make. So, the score is actually very layered. There’s so much more music than you can actually hear. Scot is an incredibly remarkable musician. He’s not only a very emotional kind of a person who embraced the romance and the sentimentality of the piece, but he also worked very closely with the programmers at Google. I needed people who understand both sides of the work. Bridge people. Scot and Max were both that way.

AV: Speaking of music, during our first meeting (that was in Paris in 2002, for the release of Treasure Planet), you told me that one of your dreams was to create a animated sequence on Beethoven’s 9th symphony. Twelve years later, what became of that dream?

GK: As a matter of fact, that’s exactly what I’m working on now! That’s the highest mountain to climb! I woke up this very morning with thoughts about how to communicate this. I always thought Fantasia imposed stories for the pieces of music, and it bothered me a little. I think that this is going to be less Disney in the approach and much more of a creative and artistic expression celebrating what’s already in Duet: Destiny, the purpose of mankind, and ultimately, the blessing of joy, which is very much what Beethoven’s music is about, especially in the last movement. In this case, I’m really trying to express and describe what I think is actually existing in the music. I’m really hoping and praying that all the inspiration I need and resources come together just like they did for Duet.

You know, we aren’t in control of all of these things. We’re artists with our hands waiting to receive inspiration. You need humility to create art. I never liked the idea that animation is an industry. My calling is really as an artist. That’s the foremost approach in my animation. Now, leaving Disney, I’m enjoying this freedom to express myself without the constraints of a big studio. It’s just more difficult to actually find partners to do that kind of animation. That’s one of the goals now. Google is a wonderful company because it has access to pretty much every human being on the planet. Also, this is not Hollywood. Working in the Silicon Valley creating animation was really an unusual event. To create a little animation studio there was really refreshing. You can’t help think things differently there.

So, as you can see, at the time we first talked about it, it was just a dream and now it’s actually becoming a reality.

Be sure to watch the Making-of featurette for Duet here

Filled with great admiration, we express our gratitude to Glen Keane. Very special thanks to Fumi Kitahara.