Walt Disney Pictures (November 18 1988), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (August 6 2013), Blu-ray plus DVD, 74 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition 1.85:1, DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1, Rated G, Retail: $29.99

Storyboard:

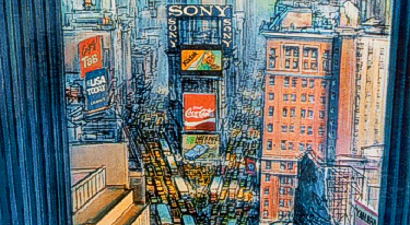

Charles Dickens’ classic story of little orphaned Oliver is given a delightfully contemporary Disney twist, swapping the action from ye olde Victorian London town and planting it firmly in the bustling, hyper-hip streets of 1980s New York City.

The Sweatbox Review:

Joining Disney’s concurrent releases of two other “secondary” titles from successive decades (the 1960s’ Sword In The Stone and Robin Hood from the 1970s) in new Blu-ray HD updates, I can still very vividly remember the first time I saw Oliver & Company, the Studio’s 27th animated feature first released in 1988. And despite the film widely being seen as something of a lesser entry in the Disney canon since, my memory of Oliver & Company sticks with me: there was something new and different going on here that suggested a new direction in where the company’s animation department was headed. Previous films to Oliver very much retained the traditional feel of the movies that had followed Walt’s death in 1966 and even The Fox And The Hound, despite some rather stronger than usual emotional moments, felt very much at home with the likes of Bambi and The Jungle Book.

In 1985, The Black Cauldron made an earlier attempt at announcing a new kind of aspiration for Disney Animation, but the picture almost sank under the weight of its own ambitions: expecting a kiddie adventure, the word of mouth quickly started turning people (mainly parents) away once they heard about the raising of a dead army of skeletons, the rather drab hero and the sucking of life out of the villain come the film’s climax. Faith in the Studio’s animation brand was quickly restored thanks to The Great Mouse Detective just one year later, a brilliantly conceived (from Eve Titus’ much more intriguingly named Basil Of Baker Street book) little movie that returned to what Disney did best, but did it quick and economically, keeping the animation division off the chopping block for a little longer at least and arguably providing the groundwork for the renaissance to come.

Asserting his position as head of the Studio, then-new head Jeffrey Katzenberg picked the story of Oliver Twist as the unit’s next film, but this being the 1980s period when Disney was turning its fortunes around by hiring in some of the biggest names in entertainment and enjoying enormous success as a result, the onus here was to be on a contemporary telling that could accommodate some of the talent the Studio already had deals with. It was seemingly a knock-on effect from the live-action unit that essentially washed the floors of Disney Animation clean: although Mouse Detective had been enough of a hit, it had still been the kind of entertainment – a typical “Disney picture” – that one would usually associate with the Studio. With Oliver the goal was to open up the audience awareness factor by expanding an animated film’s appeal, pulling in new audiences and making the kind of money that live-action, and Disney’s own animated hits of the past, could make.

Just a couple of years earlier, Disney had been given a wake-up call by Steven Spielberg and Don Bluth’s An American Tail, which had proven animation wasn’t just for kids, a popularly conceived notion that the medium had been all to happy to accept and become stuck in a rut with. That film had outperformed Disney’s offerings in several markets, the slightly more mature story and enormous success and appeal of Linda Ronstadt and James Ingram’s smash hit Somewhere Out There going as far as to bring in their fans to see the film the song was associated with. It wasn’t the first time a song had been one reason audiences kept coming, even in animation, but it reaffirmed the fact that music and animation made for good bedfellows, and a liftable ballad from a film’s score could not only win critical acclaim apart from the film, later in a series of almost regular Oscars, but also help promote it on the radio and in the singles chart at the same time.

Thus Katzenberg lined up a still impressive number of musical talents whose differing styles would pull in a varied audience as well as sonically illustrate the melting pot sensibilities of New York City. So we have the power balladeering of man of the moment Huey Lewis (hot off Back To The Future’s two hit songs), the slick studio produced pop of Billy Joel, the Latina influence of Reubén Blades, Ruth Pointer injecting a healthy dose of urban soul and Bette Midler making a big splash for Manhattan’s famous Broadway with a show-stopping turn of epic proportions. Behind the songs the composers weren’t too shabby either: the Lewis’ performed opening Once Upon A Time In New York City not only raises the curtain very cleverly but was also none other than lyricist Howard Ashman’s introduction to the Disney Company.

Ashman had been a huge Disney fan all his life, and the musical version of Little Shop Of Horrors had propelled himself and his writing partner Alan Menken to the forefront of up and coming New York composers to watch. His participation in Oliver & Company’s opening really should not be underestimated: the lyrics show the kind of simple but vastly effective wordplay that Ashman would complement Menken’s music with in such following films as The Little Mermaid, Beauty And The Beast and Aladdin, the Broadway infused blockbusters whose success was very much down to Ashman’s storytelling songs. And that whole attitude begins at the start of Oliver & Company: where else will you hear the words “Once Upon A Time” set to contemporary music, evoking both a classic storybook feel and clearly providing an up-to-date setting in one hit.

Likewise, many of the artists brought their record producers along with them: Stewart Levine, Phil Ramone, Tom Snow and Willie Colon each get credit, while Midler’s big production ensemble piece Perfect Isn’t Easy was the benefit of a Studio in love with one of their biggest star names (the recently revamped Disney placing a fading Midler in such crude but funny comedies as Down And Out In Beverley Hills, Outrageous Fortune and Ruthless People and watching the profits come rolling in) and open to indulging every whim. Midler’s choice for co-writer and producer on the song was her old touring show composer, a singer-songwriter you may have heard of named Barry Manilow, the pair working together to provide a knowingly old-school show-stopper that, while not the best example ultimately in the Disney catalog, is big fun and allows Midler to unleash her inner bark quite literally!

Trying to make sense of all this was score composer J.A.C. Redford, most often found in movie credits as an orchestrator (indeed, on many of Menken’s scores) but a fine writer in his own right and who here manages to not only bring the various styles and musical attitudes together cohesively but makes everything sound like it’s coming from the same place. A highly subtle but pinpoint sharp example of this is the film’s very opening moments: on the soundtrack album Once Upon A Time In New York City is very much a pop ballad; in the film, accompanied by Redford’s light strings, it’s part of a wider-encompassing, legitimate score. Just listen to the Bedtime Stories scene and notice how he weaves Dodger’s saxophone into the score, or sit around for the end credit suite and marvel at how he brings all the themes together orchestrally, in a different arrangement to what featured on the soundtrack album.

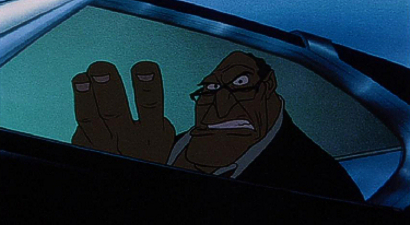

Even with its unfair sub-Disney reputation, by now I’m sure you can tell that I’m more than a bit of a fan of Oliver & Company, and it’s not just because of the music. Back at that first screening I was also struck by the visuals, in particular a scene that until that point could have only have been achieved in live-action, unless painstakingly drawn out by an artist working on just that one shot for as long as the film was in production. And it still wouldn’t have looked as good. I’m speaking, of course, about that moment when the grand villain of the piece, the infamous gangster Sykes, is revealed, the camera gliding up from the beaming headlights of his automobile, over the hood and around the side, trucking up to the window as it slowly begins to draw down…man that was amazing stuff to see, not only being vastly impressive technically, but a terrific judgement on the part of director George Scribner on where to really use his limited early computer animation shots for maximum benefit.

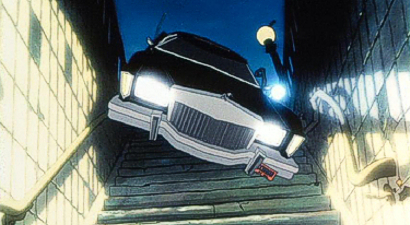

CGI is all-too prevalent today, but back in the days of Tron and The Great Mouse Detective’s climactic Big Ben mechanism scene, much of this computer trickery had to be printed out in wireframes, traced onto cels, and ink and painted along with the characters. At least the process meant that the computer could work out the shots, angles and line work, and though the simpler geometric shapes may now sometimes stand out to audiences more familiar with purely CGI’d softness, there’s an impressive amount of computer rendering going on in Oliver that far surpasses the exciting workings of Big Ben in Mouse Detective and makes an extraordinary amount of detailed work – the New York subway chase, Midler’s character’s stairway descent in Perfect Isn’t Easy, not to mention various props and backgrounds – possible.

When I saw that reveal of Sykes, it was this moment that defined the new Disney for me, the combination of technology being used to forward the storytelling providing the real buzz that remained the talking point between myself and the friend I saw the film with long after the movie was gone from theaters. When Oliver finally hit VHS – and the time between theatrical and tape releases was extraordinarily long thanks to a reissue in 1996 – I was eager to see if that scene held up on screen as it did in my mind. But as I fast-forwarded through, I began to catch other moments in the film that are just as impressive for other reasons. The storytelling is very tight, as one might expect having borrowed the source from an old master, but Disney’s tweaks, subtractions and additions really do go a long way to delivering the same basic plot while navigating around several, it has to be said, rather convoluted twists from Dickens’ original (and tells it in half the time Carol Reed’s famed 1968 movie version does).

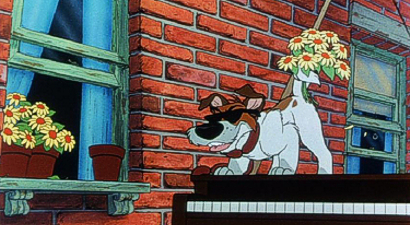

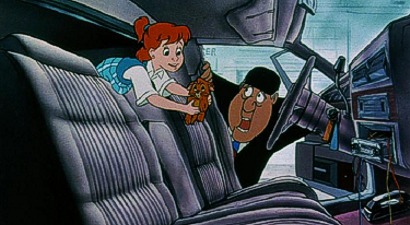

The characters are great: Oliver himself is now an orphaned kitty, lost on the dangerous streets of Manhattan until he befriends streetwise mongrel Dodger and joins a gang of down and out dogs of various breeds and temperaments who hang out with human pickpocket Fagin. As per tradition, Fagin finds himself under the dastardly thumb of the villainous Sykes, now a fearsome loan shark with a ruthless pair of Dobermans at his disposal. With money owed to Sykes within days, Fagin’s canine chums take it upon themselves to attempt to liberate a fancy limousine’s car stereo system in order to have something to pawn: a scheme that turns sour when Oliver is mistakenly left behind. Taken in by a delightful young girl, Jenny, Oliver is soon used to the high life, much to the dismay of Jenny’s over-pampered pooch, pedigree poodle Georgette (the exuberant Midler). Wanting Oliver out of the house, Georgette is pleased when Dodger and pals spring the cat…leading to Fagin spotting Oliver’s new golden collar.

Receiving a ransom note for the return of her pet, Jenny sets out to track down Fagin, but when Sykes turns up for his money, a kidnapped cat is not what he had in mind and he sets his sights on catching Jenny for ransom instead… With these contemporary updates, Oliver & Company is certainly a product of its time, 1980s filmmaking being full of violent, edgy and sometimes quite stark pieces on screen. Of course Oliver isn’t truly scary, but this is Disney doing something more modern on a scale like they’d never achieved before, and as such it does hold up today. There’s still the quality storytelling and animation going on, but there’s also an unmistakable new approach, that this is more realistically believable than usual, albeit within the confines of an animated movie. But it never feels glib: the various characters – the dogs and humans do not “speak” to each other, only themselves – never feeling like poorly written stereotypes or being asked to provide an empty cool factor instead of good character development. Part of this is down to the voices being the characters they are, part of it is simply down to a good script.

As Fagin, Dom DeLuise has more to play with than with some of the other animated characters he’s lent his voice to, and it’s easily his best animation performance alongside Jeremy in The Secret Of NIMH. Shedding his portly real life appearance, DeLuise’s Fagin is a starved scruff, barely there in form or nature: he hates the situation he’s in, but makes the best of it, warming to his animal companions as the only friends he has, but knowing it’s going to be a tough slog to try and pull himself out of the ongoing circle of low life he’s gotten himself into. A stark contrast is Sykes, voiced with intimidating menace by Robert Loggia, surely the most genuinely scary Disney villain in years (and of the hefty bulk that typifies Glen Keane’s designs). That’s he’s not full of magic, a hint of humor or the benefit of a comedy sidekick really helps keep the character focused: this is a frightening, real-world guy who keeps two very vicious and dangerous dogs by his side. We all probably know of someone like this, an overbearing thug who’s never quite as welcome or as classy as he likes to think he is, and as such that’s why he works so well.

Some criticisms were aimed at the film at the time of release for just how real Sykes came over (one might argue he’s a live-action villain in an animated film that sometimes plays more along the Touchstone sensibilities of the time), but surely that’s another sign of good portrayal and strong performances from artist and vocalist? Whatever, Sykes is as fear-provoking as he needs to be in staying true to Dickens, making his ultimate end – arguably Disney’s only onscreen death and the strongest pay off until Tarzan’s Clayton a decade later – all the more delicious. The slightly rough and real nature extends to the artwork too: Oliver & Company marks an intentional return to the Xerox process inaugurated with One Hundred And One Dalmatians but here, rather than a shortcut or statement in style, it’s actual production design. It’s not always successful: some of the rougher lines sometimes look as if they’re over egging the process and it doesn’t help those CG-aided yellow cabs from feeling somewhat out of place, but there’s the definite funky vibe one gets from the hot, sweaty big city and added touches such as actual product labels for Coca-Cola, USA Today, Kodak and other trademarks play no small part in creating an atmosphere that we can relate to and, therefore, follow the characters through with an added level of acceptance. Also adding perspective – literally – is the aforementioned computer animation, which allows director Scribner to set up some unique angles for an animated film, and kudos to Disney for not retro-erasing the often glimpsed World Trade Center towers from the skyline shots.

Not to say Oliver isn’t a whole heap of fun: Joel’s signature moment Why Should I Worry? (a song that really should have found success as a single and foreshadows Phil Collins’ similar You Can’t Hurry Love) finds some familiar faces from Disney’s doggie past peppered among the crowds, a nod and a wink anachronism that simply works due to the energy of this particular musical number, and Joel’s performance – and he’s none too bad in the speaking role either! As Oliver, a young Joey Lawrence brings a real youngster’s perspective to the part (he was twelve at the time) and Midler of course shines in perhaps the film’s oddest moment, Perfect Isn’t Easy. Odd? Well, while the rest of the film plays with the sounds of the city, Georgette’s number is old-school Broadway – a major piece of the New York puzzle to be sure – but one that might be overindulged here. I’m never too sure of this sequence: it’s certainly a good number, but Georgette is a secondary character who seems to have been given a big moment only because of who is voicing her. I like Perfect Isn’t Easy, but it’s also the one moment when the story stops to allow for a song: it’s a lot of screen time given to setting up a character that then plays a minor role, but Midler belts it out in such grand fashion that one can forgive the weakness.

If the New Disney practically came into effect during The Rescuers, and The Fox And The Hound was the hybrid that attempted to show what the new artists could do, The Black Cauldron became the spectacular folly that taught them where their strengths and weaknesses lay and The Great Mouse Detective built on that and past tradition to promise bigger and better things ahead, then Oliver & Company is where the elements really gelled and suggested the true new path Disney Animation was about to take. Mouse Detective had washed away the rather stagnant taste of the downbeat Fox And The Hound and Black Cauldron, but for all its showing the new crowd could pull off something as effectively as the old, it’s still a film very much steeped in the Disney ethos of yesteryear. For my money, in a great new way it all begins with Oliver & Company, the film that restored truly memorable songs to the Studio’s animated films while forging ahead with fresh sensibilities and returning to the pursuit of technology, in this case the computer, and how it could make the Studio’s films more believable in a way just as the Multiplane Camera had done in decades gone by.

The $53 million Oliver & Company grossed in 1988 may sound like small fry now, but it was the first animated film to cross the $50m mark (boasting even more than American Tail’s $48m record), paving the way for the $89m grossing The Little Mermaid and the renaissance of the 1990s blockbusters that would eventually take in the changing face of animation to accommodate the kinds of CG comedies of today. I’d wager that such a film as Oliver couldn’t even be made today, not least without its hand-drawn visual charm and, continuing the run of fresh Disney hits started by The Great Mouse Detective, it’s a shame that the film nowadays gets lost between Basil and Ariel’s adventures, the old-style look somewhat out of place in the middle of those two warmly colored and inked films. Oliver & Company should be celebrated more than it is for daring to be something totally new while striving to retain the qualities that put Disney Animation on the top of the game. It’s not quite the Dickens story as we remember it, but then neither did The Jungle Book resemble Kipling closely either! Charming, exciting, amusing and a terrific thrill ride, this Oliver provides perfect company.

Is This Thing Loaded?

Disney’s August 6 titles have been a very mixed bunch; the result, I presume, of these three particular titles not ever being assessed by even big fans of the Studio’s films as among the best in its rich output. Grossly unfair on the films themselves, which all have much to recommend them, their Blu-ray releases have ranged from the dethpicable (Sword In The Stone’s awful video issues) and the satisfactory (Robin Hood’s image was much better), to the so-so, which is where we find Oliver & Company. With the Studio’s current trend of updating their films on Blu-ray format as quickly as they can, the best and worst aspect of that approach is clear: yes, our shelves will be stacked up sooner than later with the classic features (awaiting, I believe, only some films from the 40s and 90s before our collections are essentially complete), but it also means the producers of these efforts are taking the easy option and basing these BDs on the last available DVD edition rather than starting from scratch and awarding each title the respect they deserve.

As such, we’re losing the opportunity for truly definitive editions, complete with archival materials that would retain all previous extras and bring something new to the titles for long-time fans, and although at least the two previously mentioned titles rustled up at least one new extra in their jump to HD (or questionably HD, in Sword’s case!) more enticing, Oliver seems to have suffered in this trio of offerings in that it’s practically a mirror of its previous 20th anniversary DVD edition, itself a clone of an earlier DVD save for the introduction of a set-top game. It’s a title that has had an odd history on home video: after its theatrical release and waiting years for a VHS, Oliver & Company came to tape soon after a 1996 theatrical reissue, also appearing on LaserDisc at the same time and allowing for a frame-by-frame analysis of that Sykes car shot and his eventual comeuppance on the Brooklyn Bridge subway tracks…ouch!

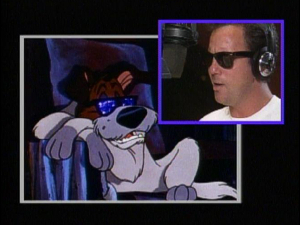

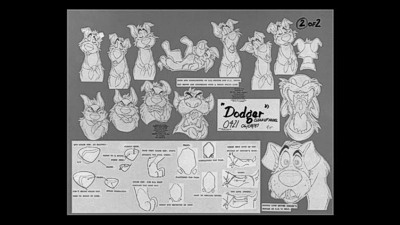

Seen even then as a secondary title in the Studio’s catalog of animated features, the film was scheduled as part of the Gold Collection series of DVDs before that too was delayed, eventually appearing as a blandly monikered Special Edition with barely a handful of bonus features, carried over with the “new” game as a feeble way of celebrating its 20th anniversary for a second DVD that was actually released in its 21st year! Now those same bonuses make their way to this Blu-ray edition which for what is now hailed as a 25th anniversary edition (well, at least they got the year right this time), although without any new extras there’s little to get excited about or, indeed, recommend this disc for. From the basic, static menu (in which Dodger looks absurdly small), topping the list again, but nonetheless most welcome, is The Making Of Oliver & Company (5:30), a 1988 featurette from a period in the middle of old-school documentary program making and the whizz-cut soundbite fluff pieces of today, back when interviews were allowed to run for more than just a sentence but with a few video effects thrown in.

Even at the (nostalgic!) slower pace, there’s some good info here, from concerns over Billy Joel’s ability to act (and he’s seen doing so wearing his shades in the recording studio) to the then all-new computer animation capabilities (described here as “the tip of the iceberg” by Roy Disney, although another quote suggests we shouldn’t look “for computers to replace human animators at Disney”), and even if it’s short and sweet this is an essential inclusion at the very least (considering the amount of other extras that the Studio could have included or, indeed, dropped from this release). Less exciting, from the 1996 theatrical reissue, Disney’s Animated Animals is an otherwise fairly simple 1:30 video spot that runs through the cast in a bid to introduce them to new audiences, while a pair of Bonus Shorts have also been included, although I am as perplexed by their inclusion as before: they’re not the most original of selections, and probably only picked because Pluto has a run-in with a couple of kittens in them, particularly the first, the often seen and over-recycled Lend A Paw.

This is itself a remake of a black and white short, Mickey’s Pal Pluto, though it did win an Oscar in 1941 and marked one of the few occasions when Pluto’s good and bad consciences got together to fight over what the pup should do (in this case to save or let a poor little kitty drown). Next is Puss Café, another Pluto cartoon in which he faces off opposite Melvin and Milton, a pair of goofy Siamese cats that caused multiple disruptions in Disney cartoons long before Si and Am came to plague Lady’s life in Lady And The Tramp. Here, the dopey pair try to take their pick of Pluto’s backyard delights, but while the cartoons play together for over 15 minutes screen time, they’re still un-amusingly the same old ropey, interlaced composite video transfers from years ago, sporting ghosted frames amongst their pre-restored grunginess and not a patch on what was offered even in the Walt Disney Treasures collection. In this HD day and age, these look like dino-toons in terms of quality…such a shame.

Mush better, although still in SD only as all the extras are, is a collection of Publicity Materials, usually a Disney no-show and proving just how desperate the Studio was in attempting to fill this disc with something! A full set of Theatrical Trailers (from the original 1988 release, a TV spot and the 1996 reissue) are still here, as is the 1996 TV promo The Return Of A Classic, which run a total of five and a half minutes all played. Coming across the original 1988 trailer really did bring back warm memories for me: I distinctly remember seeing it played in the theater and running it endlessly on VHS, and it still stirs up the same kind of excitement that I had in wanting to see the film. The reissue promo quite rightfully addresses the fact that Oliver became the first animated film to really go out and do live-action sized box-office numbers in its initial run, and its pretty cool to hear that confirmed on an official release. As a last bit of filler, an option to Sing-Along With The Movie plays the film with a subtitle track offering the song lyrics at appropriate points.

Naturally, the set-top game from the previous DVD has not been included on the BD itself, but it is still intact on the film’s enclosed DVD copy, which also retains all of the other 20th/25th anniversary compilation of extras, including the Oliver’s Big City Challenge game, which isn’t too bad even if the instructions are as complicated as they are long-winded! Basically put, one must help Oliver select the right “barking buddy” for the job at hand, be it swiping sausages from the hot dog stand, or rescuing Jenny from Sykes. There’s obviously been a lot of work gone into this, but the need to choose a dog to “help” you is an added obligation that has no bearing on things and also requires that you’ve seen the film to pick up on the clues. Nevertheless, it’s not anywhere near as fruitless or frustrating as these things can be, and although it doesn’t lead to any rewards the re-use of clips and artwork is nicely done.

Also on the DVD are a pair of Sing-Along Songs, which run the Why Should I Worry? and Streets Of Gold sequences with on-screen lyrics, while Fun Film Facts offers up some more info: nine pages of text on the making of the film that adds some decent background context to the movie, and a very welcome Oliver & Company Scrapbook presents 57 images over 14 pages, from development art including a few images from a deleted “Jungle Song” sequence, storyboards, design and model sheets (including some characters cut from the film, production stills and preliminary and final publicity posters. It’s almost just a token offering, but it’s always great to see such art, though I wish there was more on that Jungle Song, which isn’t placed in any context and sounds intriguing, while it’s also fun to remind ourselves that a certain screenwriter, Jim Mangold, would go on to become the James Mangold who directed a variety of acclaimed movies recently, including Walk The Line, 3:10 To Yuma and the current The Wolverine blockbuster. Well…you have to start somewhere!

While Oliver & Company doesn’t seem to warrant anything more, I seem to recall Billy Joel and Bette Midler attending the opening ceremony at Disneyland Paris (then EuroDisney) and singing their respective songs live on stage, and this footage may have provided a nice bit of context for viewers to see Dodger and Georgette’s real-life counterparts belting out those great tunes, and while the only other thing that feels missing here is are retrospective comments from Scribner and a couple of his lead animators, we really can’t expect that from Disney at this stage. Across both discs, Disney’s Sneak Peeks include The Little Mermaid, Planes, Marvel’s Iron Man/Hulk: Heroes United, Newsies on stage, Sofia The First, The Muppet Movie and Return To Never-Land among other promos.

Case Study:

Oliver’s original DVD release sported perhaps one of the Studio’s blandest collages of characters ever slapped together (although memories of that scary Great Mouse Detective sleeve still linger!), but the film’s 20th anniversary DVD righted that wrong and provided a more than fitting treatment that was closer to the character-centric images created for its theatrical campaign. In an unimaginative moment, the powers that be have opted to repeat the cover for this BD update (as opposed to the tweaks Sword and Robin Hood got), but to be honest there’s no harm in that: it’s a decent sleeve and does the job, even if the choice of characters on the front still puzzles me. Oliver and Dodger are here, naturally, but missing most noticeably are Fagin, Jenny, Georgette and, forgoing the chance to bring some shadowy peril to the sleeve, Sykes.

Are they on the back? Um, nope: we get repeats of Rita and bulldog Francis, joined by Great Dane Einstein, a rubber lifesaver (!?) and a lot of wasted space. Still, it is preferable to the initial DVD’s art, which was as basic as they come. Other than that, things aren’t too exciting: inserts are restricted to Rewards code and Movie Club promos, and the back forgoes the chance to offer a before and after “restoration” shot (as with Sword and Hood) or anything other than a repeat of the previous DVD sleeve, complete with Twin Tower-less New York City (again, kudos for Disney for not wiping them out of the film’s backgrounds). In keeping with the other August 6 titles, we do get a listing of the package’s contents (although the differentiation between BD and DVD isn’t noted) and, as is sadly now appearing to be a trend, there’s no mention of an aspect ratio…

Ink And Paint:

After Sword In The Stone’s abysmal use of DVNR to remove some of the animators’ original pencil lines, Robin Hood fared much better, even if there was a sneaky suspicion that some of the backgrounds might have been ever so slightly over-scrubbed with the digital brush. The same could be said here, although Oliver & Company has never really looked that great, mostly due to the grainy film stock used at the time of its production in the 1980s. Although the initial LaserDisc looked fine, the consecutive DVDs used grain-heavy, gate-weaving prints that didn’t really allow the movie to look as good as it could, so it’s pleasing that it has at least been given some attention in this area.

I would, personally, have preferred a transfer that left a little more filmic information in the image – the transfer for The Rescuers and its sequel being what I would call perfect representations of what Disney animation from this period should look like – but it seems the engineers are now interested in aping the frame-by-frame restorations of Disney’s Diamond Editions by electronic means, enforcing a “clean wash” setting on a perfectly good HD transfer to wipe away just a little too much grain. The results aren’t bad, and in fact Oliver & Company has never looked so good, but there’s just a feeling it might be a bit too clean (although any softness noticed is actually a by-product of the original production process).

Otherwise things are intact: after The Great Mouse Detective’s experimentation with coloring the animators’ Xeroxed pencil lines, there’s a return to the (sometimes harsh) black outlining, which was picked presumably to mix in with the many computer-generated props and vehicles, which were printed out and traced onto cels. Thus Oliver & Company is an artistically interesting film from Disney’s, marking the point when CG animation really started to creep into the production of these films (The Little Mermaid, next, would then experiment with actual CG rendering of two scenes in that film), as well as being the last use of the Xerox process and the heavy, jazzy look of those kinds of backgrounds – although any reservations on the animation throughout the movie can be put down to saving the best for last, in the awesomely directed, fast edited and terrifically colored and shaded climax.

Which is what makes Oliver visually appealing, to me at least, because a few static backgrounds aside (and, let’s face it, it was always going to be hard to create a hustling, bustling New York in hand-drawn animation on a budget), there’s always something going on in the frame. Sure, the film has a rough and ready feel, but it also has an energy in those backgrounds and character animation that we haven’t seen since. The 1.85:1 aspect may crop a little top and bottom from the 1.66 ratio of the original negative, LaserDisc and previous DVDs, but this is how it was shown theatrically and there doesn’t seem to be any instances of the framing being too tight, and it certainly gives the film a grander scale to the visuals. While I might have preferred a 1.66 frame and less digital scrubbing, Oliver & Company should please its fans.

Please note that the screenshots in this review are for illustrative purposes only and not representative of the sharpness and detail to be found on the Blu-ray Disc in this set.

Scratch Tracks:

A pulsating experience on LaserDisc and DVD, Oliver was among the first animated features to use a full surround mix and attempt to create real atmospheric effects for its locations, from the streets of Manhattan to Sykes’ dark and dingy dockyards. The film was mixed at a time when digital tracks were still relatively new and sound designers were pushing audio effects to the fore (indeed, some of the tracks from around this time can sound quite piercing to audiences nowadays), but this 5.1 configuration presumably based the 1996 reissue sounds as good as animated films come. Although it sounds to me to be the same track as from previous editions, the mix itself is more dynamic, easily pulling the best out of what Oliver & Company has to offer. English subtitles are optional, as are dubs and subs in French and Spanish, repeating the decent Dolby tracks from the DVD.

Final Cut:

With only a handful of supplements – if, in the case of the added cartoons, one can even really call them that – to have ever accompanied the film on disc in the past, Oliver & Company unfortunately isn’t the recipient of even a scant new token extra, but at least is doesn’t lose what it just about already had. Although one of the best extras, the scrapbook, is only to be found on the bundled in DVD, the Blu-ray does retain a couple of brief featurettes and, unbelievably, theatrical trailers that show just how desperate the Studio was in finding something – anything! – to bolster this release with. If they’d looked a little harder they would have found more (such as that footage of Joel and Midler singing their respective songs live) and if they’d actually cared they would have staged a retrospective or pulled Scribner into a vocal booth to reminisce on his film. So this isn’t a definitive treatment by any stretch (as evidenced by a list price over $5 less than its two August 6 cousins), but all previous extras are here one way or another, and those coming to the title for the first time will find a little bit of context that should satisfy. As for the movie itself? Well, spectacularly entertaining, packed with great touches, toe-tapping songs and a superbly thrilling climax all shown off in a nice new transfer, it’s good to see Oliver & Company getting some recognition. Does it deserve it? Absotively posalutely!

| ||

|