At Animated Views, we can but celebrate that celebration of fifty years of Peanuts TV specials proposed by Chronicle Books. A long-awaited compendium, The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation offers for the first time an in-depth look at the art and making of the beloved animated Peanuts specials.

At Animated Views, we can but celebrate that celebration of fifty years of Peanuts TV specials proposed by Chronicle Books. A long-awaited compendium, The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation offers for the first time an in-depth look at the art and making of the beloved animated Peanuts specials.

From 1965’s original classic A Charlie Brown Christmas through the 2011 release of Happiness is a Warm Blanket, animation historian Charles Solomon goes behind the scenes of all 45 films, exploring the process of bringing a much-loved comic strip to life.

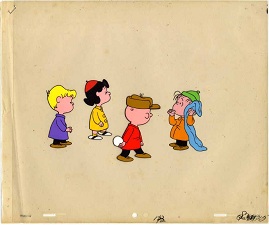

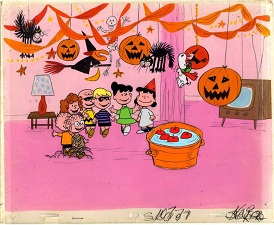

The book showcases the creative development through the years with gorgeous, never-before-seen concept art, and weaves a rich history based on dozens of interviews with former Peanuts directors, animators, voice talent, and layout artists, as well as current industry folk.

Filling a void in animation publishing, this must-have volume celebrates five decades of the artistry and humor of Charles M. Schultz and the artists who re-imagined the comic for the screen.

Animated Views:

Can you tell me about your personal relation to Peanuts?Charles Solomon: I assume I started reading the strip as a small child, but I don’t remember beginning to read it or discovering it. Peanuts was always there. During high school, I began buying the books, and as an undergraduate at UCLA, I bought them in French, for practice.

AV: How did you find the process of researching about Peanuts?

CS: I had very mixed emotions going over the interviews I had done with Charles Schulz, Bill Melendez and Bill Littlejohn: I liked and respected all three men and miss talking with them. Rewatching some of the films, I discovered bits of animation I had forgotten, e.g. Snoopy having fits while playing tennis in Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown and the unicycle sequence in Life’s a Circus.

AV: Apart from the obvious success of the comic strips, how do you explain the success of the animated films, how do you explain those films’ influence on present-day animators?

CS: I think my friend Chris Sanders (Lilo and Stitch, How to Train Your Dragon) summed it up when he said, “People ask me, ‘Where did you get your style?’ It had to come from the things I saw as a kid. If you went back in time and changed what I saw, I would draw differently today.” Animators saw those specials as kids and they clearly had a lasting impression. If you’ll pause, you can still hear Linus’ recitation of St. Luke in your head.

AV: How did you gather all the incredible material for the book?

CS: The visual material came from a few collectors and the Schulz family, and Bill Littlejohn’s daughter Toni graciously allowed to me go through the drawings her father left. For interviews, I tried to contact everyone I could find who had worked on the films. A few people were too busy, but most were very gracious about sharing their time and memories. And I had interviews of some of the artists from years earlier.

AV: In the book, you write that Schulz, who did 100% of the strip for almost 50 years, could be a generous collaborator. Can you tell me more about how involved he was?

CS: I know Schulz wrote the basic scenarios for all of the specials made during his lifetime, and he sometimes said he would like to have been more involved in them if he weren’t so busy. He clearly trusted Bill Melendez to create movements, actions and cartoon “business” for his characters. Jeannie Schulz said he regarded the films as his characters, but not his work. Beyond that, I don’t feel I can speak for him

AV: Did the producers ever get comfortable knowing that they could just keep producing the specials after their first few successes, or did they still live order-to-order?

CS: Producer Lee Mendelssohn worked with Melendez and Schulz for decades and said they enjoyed the freedom to do as many or as few specials a year as they chose.

AV: Was the production of the theatrical films appreciably different from the TV specials?

CS: My impression is that the films were handled like the specials, but the longer format and larger budget allowed them to do things they couldn’t in the specials. Snoopy’s fantasy hockey game in A Boy Named Charlie Brown takes up too much time and would probably be too expensive to fit into a special; I suspect the same is true of the “Fundamental-Friend-Dependability” sequence in Snoopy Come Home.

AV: The Peanuts shorts offered a new approach to animation music through jazz, which has greatly influenced film scoring up to today.

CS: John Hubley was really the first to combine jazz and animation; he had worked with Bill Melendez at UPA and Melendez admired his work enormously. Vince Guaraldi’s music seemed so perfectly matched to the visuals—and became so popular on its own—I don’t see how it could help but influence many younger composers and musicians. I’d be curious to hear what Randy Newman would say to the question…

Our thanks to Charles Solomon and April Whitney!

And very special thanks to Randall!