It was back in the days when Disney animation was encountering big changes, and the most successful family movies weren’t coming from the House of Mouse anymore: they were the likes of Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark, from other studios.

It was back in the days when Disney animation was encountering big changes, and the most successful family movies weren’t coming from the House of Mouse anymore: they were the likes of Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark, from other studios.

It was back in those days when Walt’s son in law, Ron Miller, ran the company, and he wanted to change its fortunes, with a big, animated adventure epic that would not only please the young and the old, but most importantly the elusive teen audience.

With a wealth of similar “sword and sorcery” features hitting screens, an animated version of Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain series of books seemed the perfect idea. But how to make a coherent 80-minute-or-so story out of the five volumes of the original material? And how to experiment something fresh without discarding the Disney heritage?

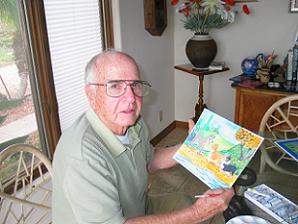

It was back in those days when this near-impossible task was assigned to Joe Hale, who had come at Disney in 1951. Starting work in the animation department as Ollie Johnston’s assistant on Mr. Smee, then with Ward Kimball on Man and the Moon and other shorts, before moving on to special effects with Mary Poppins, Pete’s Dragon and Bedknobs and Broomsticks, and a new generation of Disney live action movies like The Black Hole and Watcher in the Woods, Joe was well placed as the perfect person to bridge the connection between the old and the new.

With the eventual result now restored and released in a new 25th Anniversary Special Edition from Walt Disney Home Entertainment, we stirred up the cauldron once again, to speak with the man who charged with mixing those ingredients together…

Animated Views: How did you go from layout man to story man and then producer of The Black Cauldron?

Joe Hale: Well, basically, I started on delivering the mail around the Studio. Then I went on doing animation, notably on Man on the Moon and some TV shorts. I’ve done a little bit of everything, like story work. Basically, I was a layout man, but on The Wonderful World of Disney and Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color I got experience in the combination of live action and animated characters. Walt would be with Professor Owl or Donald Duck or Chip & Dale or whatever. So, I started kind of jumping back and forth between live action and animation.

Joe Hale: Well, basically, I started on delivering the mail around the Studio. Then I went on doing animation, notably on Man on the Moon and some TV shorts. I’ve done a little bit of everything, like story work. Basically, I was a layout man, but on The Wonderful World of Disney and Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color I got experience in the combination of live action and animated characters. Walt would be with Professor Owl or Donald Duck or Chip & Dale or whatever. So, I started kind of jumping back and forth between live action and animation.

Story-wise, I worked on films like Watcher in the Woods. When I came back, I was given the choice of directing or Story. At that time there was another person, Rick Rich, who was already kind of directing. He was kind of a junior director and I didn’t want to get in his way. So, I just stayed in Story.

You know, there was a lot of trouble going on at the Studio. The Nine Old Men as they called them at that time, Frank & Ollie, Milt and all those guys were gone and then there was another group that was very talented and experienced that left with Don Bluth. So, we had a bunch of young animators from Cal Arts that had talent but that didn’t have the experience, and everybody knew I was always eager to bring the young ones along.

Ron Miller called me up and asked me if I would take over as producer on The Black Cauldron. I think some of the animators did talk to him, or talk to someone, about me taking over the producing, but I didn’t want to do it because a good friend of mine, Art Stevens, was the producer and I just didn’t feel right about it. And at that time, I was more interested in live action and I talked to Ron about second unit live action directing. Anyway, Ron finally told me that whether I took the job or not, Art was gonna be replaced by someone else. So, I took over The Black Cauldron.

AV: What kind of problems did you encounter while working on the story of Cauldron?

JH: You know, there was like five books – The Chronicles of Prydain – and the Studio had already spent 7 or 8 years. I wasn’t involved in it then. There had been a lot of storyboards that went on and off. So, for me, it was really a matter of trying to pull the whole thing together. So, that’s basically what I did.

AV: The film was shot in 70mm. Was that a tricky part of producing the movie?

JH: Actually, that part was not that difficult because we’ve been doing films in CinemaScope. It was a just matter of having a lot more animation and bigger backgrounds. So, it was probably a bigger problem for animation than it was for layout.

AV: Layout is somehow one of the most obscure parts of the animation process. Can you tell me about that not-so-well-known art?

JH: Basically, there were a lot of very talented animators. There were the Nine Old Men, and other animators that were talented as well. So, there was – God, I don’t know – thirty animators working at the time and I figured that I didn’t want to be an animator. So, I got to my boss, Andy Engman, about getting into Layout. What the Layout man does is: he takes the storyboard and breaks it down into individual scenes. And then you draw, you “lay out” that scene and you make drawings of the characters. You work very closely with the director and you have a lot of input.

On Cauldron, being a Layout man, I was heavy on layout. Cauldron is really a layout man picture. What I wanted to do was show the audience the world that they’re placed in. So, I wanted a lot of long shots. The way we approached layout in those days, like in the pictures that Walt was involved in, was we approached each scene as if they were a painting that you could frame and hang on a wall. We made each scene very attractive. The layout man is like an art director. He’s certainly like an assistant director combined with art directing.

Somewhere along the line, they started to call it Layout, but most people never knew what layout really meant. The Layout men are the unsung heroes of animation because nobody knows what we do. When you look a scene on the screen after it’s painted, the people say “oh, what a beautiful painting!”. The background men pretty much get the credits for it. But basically, it was all designed by a layout man with just a pencil, a black and white drawing that the animator and the background man could follow.

AV: Can you tell me about the creation of the visual style of Cauldron, that we owe for a great part to layout stylist and newcomer Mike Hodgson?

JH: Mike was a very, very talented guy. I liked his approach and his design. He worked together with Don Griffith [art below]. It was a combination of both their styles. I wanted this picture to have a little different look but I still want to have a style typical of Disney.

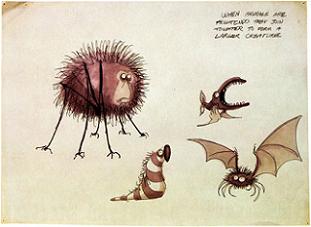

AV: A more atypical artist was Tim Burton [art below].

JH: (laugh) He had a large room next to my office, and he was doing all of these weird drawings. They were so sketchy and they didn’t work in animation at that time. He had a lot of influence on the picture, but not on a particular style. He was very talented, very imaginative.

AV: Black Cauldron was produced under the guidance of both Roy E. Disney and Jeffrey Katzenberg. How did that work?

JH: I had known Roy for a long time. When he came back to the studio, I worked very closely with him – a lot more than with Katzenberg. Roy wanted to be the head of animation, and Katzenberg wanted that also and each one of them didn’t want to give up any of their power. So, there was kind of a struggle between Roy and Katzenberg and I was kind of caught in the middle of it. I was with Roy because he grew up with Walt and spent his whole life in animation. So, I had more faith in Roy in the long run than with Katzenberg.

AV: Disney is about to release the Diamond Edition of Beauty and the Beast and I know you happened to be part of the earliest version of the movie. Can you tell me about that?

JH: I got to work on Beauty and the Beast together with David Jonas, who is the greatest story sketch man in the world, and veteran story man and designer Al Wilson. We did some boards on Beauty and the Beast and had a couple of story meetings but Eisner didn’t want to do another fairytale. He wanted to do something more up-to-date, with Cindy Lauper, Billy Joel… He wanted something in which he could use popular art. Anyway, I love Beauty and the Beast. I think that’s the best thing they’ve done probably since I left!

Our gratitude goes to Joe Hale, Jacqueline Cavanagh, Beth Eyler Castle and Didier Ghez