Walt Disney Pictures/ImageMovers Digital (November 6 2009), Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment (November 16 2010), Blu-ray plus DVD, 96 mins plus supplements, 1080p high definition 2.40:1 widescreen, DTS 5.1 Master Audio, Rated PG, Retail: $39.99

Storyboard:

Miserly old skinflint Scrooge is visited by three spirits one Christmas Eve, who show him that his money-grabbing ways are not the things he should be focusing his life on.

The Sweatbox Review:

Robert Zemeckis used to be my favorite director. In fact, in many ways he still is, even if his recent attempts to squeeze anything near resembling a human performance from his computer generated puppets in such films as The Polar Express and Beowulf have left me stone cold and lamenting this once great filmmaker’s descent into the Dark Side. Where was the innovative and visually ingenious mastermind of the Back To The Future trilogy, the man that forced animation to find its perspective for Who Framed Roger Rabbit, or who pioneered computer-assisted effects in such varied fare as Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact, Cast Away and What Lies Beneath?

In recent years he has thrown away the rough shot conditions of live-action and confined himself to The Volume, a hideously conceited term for a motion-capture stage, where Zemeckis has now spent almost a decade trying to convince us that a mo-capped Tom Hanks or Angelina Jolie are better than the real thing. Well, they aren’t, and the films have failed creatively as a result. But still Zemeckis tries and it has to be said that when I heard he had secured the services of a certain Jim Carrey for this attempt, I did wonder if the actor might have what it took to break through falsities of the mo-cap method and finally bring life to the dead-eyed “uncanny valley” characters that populate these films. Well, Carrey largely does and, prepare to be shocked, Zemeckis is back. Kind of.

Apart from the early November theatrical release date – replicated here on home video – simply being too early to watch a Christmas movie, my underlying disappointment with the motion-capture process (and let’s stop calling it performance capture – certainly the end credits of this very film do away with that overcomplicated term and settle for plain old mo-cap) was the reason I, frankly, wasn’t originally jumping at the bit to catch Carrey and Zemeckis’ collaboration last year. When dealing with an actor of, say, Andy Serkis’ ability to render what the animators need in order to then pull out a true performance for characters like Gollum or Kong, the performer understands what he is performing for. With the likes of Anthony Hopkins or Ray Winstone in Beowulf, all they are giving is a pure stage performance, leaving the animators little to play with in terms of being able to broaden the caricature. It was ridiculous that the short and stocky Winstone was cast to play the tall and buff Beowulf, but he was so, just because it could be done.

But Zemeckis seems to have learned a lesson, and in A Christmas Carol he casts people closer to the characters’ natural builds. And this time out he has a performer in Carrey that understands that animation is a broad medium. Just like paper tracing rotoscoping leads to boring and flat human animation, which is why Gulliver was such a black hole of personality in the Fleischers’ Gulliver’s Travels, simply relaying the actions of a motion-captured actor via a million ping-pong balls into computer generated character data produces the same flat result. Carrey, however, is a very visual performer, someone who even if asked to act out a small moment will embellish it with wild subtleties that may mark him out as hammy (or “overactor” as he was hilariously called in one of the Liar, Liar outtakes) but turns out to be perfect for the motion-capture process.

Now, before I start gushing that this is a great step forward for the process, let me just say that I am 100% split right down the middle at the results of A Christmas Carol. It’s without doubt a clever attempt to return to Charles Dickens’ text, originally a serialised short story, and the opening frames set classic Disney style on a copy of the book suggests this should really have been called Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol to differentiate it from the multiple other screen versions (including two of Disney’s own). If anything, it’s the immortal power of the plot and Zemeckis’ adaptation that succeeds in pushing A Christmas Carol just past the motion-capture confines that still limits more than several certain aspects of the film.

Carrey, who will remind British sitcom fans of Wilfrid Bramble’s turn as the old Steptoe in the legendary comedy Steptoe And Son (remade in the US, without Bramble, as Sanford And Son) actually gives what could quite possibly be his most convincing straight performance ever. His Ebenezer Scrooge is magnificent, old and crotchety but never keeping still and a constant parasitic presence. But as much as I was almost – and found myself wanting to be – drawn in, frustrating details kept appearing to me, even though I wasn’t looking for them and didn’t want to be distracted. Clothes, for instance, should not stretch on a human if they bend their arm as if they have been painted on them, which led to my constant and annoying picking up of every forearm on every character being too long, especially when they bent their arms. This is a basic, direct-to-video no-no, not something that should have been missed in a much bigger budget production under an undoubtedly much more talented crew.

And, while Carrey is unique, the other actors can’t even begin to match him, the unfortunate aspect of the mo-cap process that mirrors rotoscoping coming to the fore with any kind of rapid movement: there are lots of times when characters slip, fall or move actively and it is as if there is an invisible force working against them (even a wood fire seems overly fashioned to perfection as to be bland). This slo-mo look only goes to work against the performances more, Colin Firth’s Nephew Fred, who looks like his face has been overly made up in latex, the worst of the bunch with, I’m sorry to point out again, the dreaded blank eyes, a trait also shared by Gary Oldman’s Bob Cratchit. There’s just no movement around the eyes, which are crying out for a few more muscle details, and even when Scrooge has a glint in his eye, like Marley’s door knob reflection or the flames of a fire, the eyes look plastic. All they need to do is make the eyeballs themselves more moist looking, and they might be on to something!

But there is good and, like Monster House, this time Zemeckis is serviced by a strong story, lean and mean so that the film gets right to the point without any artificial padding. A theme in the film is dual identities, and not only is it an interesting concept to suggest the three Ghosts, which come to visit penny pinching meany Scrooge and suggest he change his ways, are subconscious facets of Scrooge himself, but equally fascinating is Oldman as both Scrooge’s previous partner Jacob Marley and his current employee Cratchit. Marley himself does look as badly rendered in the final as the stills and trailers suggest, his eyes looking bitmapped on without any depth. The character, also, is quite dreary; Zemeckis has an actor of Oldman’s ability at his disposal but wastes him without tapping into any underlying layers and missing an opportunity to let him burst out of his ghostly confines, the result bringing nothing new to the character, or his on screen appearance, to beat the haunting memory of Alastair Sim’s 1951 feature film.

It’s almost as if Zemeckis seems to be so in awe of his own technology and so interested in wowing us with the “big” details that he forgets the small ones, like using the tools at hand to create something we have never seen before, instead of a CG edition of many things we have. An example is that the director quite often likes to spin us around London via swirling aerial camera swoops, but there’s nothing particularly out of ordinary in Doug Chaing’s perfunctory production design so it just looks like Victorian London has looked in many films we’ve seen before, however impressively rendered it is. Another example is a terrific chase sequence towards the end, ruined by some bits of business for Scrooge that feels tacked on and drops some hideous video game extras into his way. And then Zemeckis doesn’t know when to cut, the chase turning into an overproduced cartoon with plenty of perspective background animation that was amazing back when Aladdin flew through the Cave of Wonders but just feels old had now the same trick turns up in every CG animation movie these days.

Much of the text is taken from Dickens’ original, which sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. There’s an emotionally pivotal scene, where young Scrooge is dumped by his finance, played by Robin Wright Penn, but the sudden lapse into aged prose means that the language won’t register to everyone. Of course, actions speak louder than words, but since she is unable to make authentic eye contact because of the feeble mo-cap work, there’s a lack of true emotion, and one or two “did she leave him?” questions from younger audiences. The scene with Scrooge’s sister Fanny is even more cringe-worthy, and I can’t say much better for Bob Hoskins as Fezziwig and, repeating the dual identities notion, Old Joe. You’d think that Hoskins would be the perfect Fezziwig but, begging the question of why these films are not just shot with live actors who are matted into backgrounds afterwards, is the sight of Fezziwig dancing – Hoskins’ mo-capped head bobbing about statically and obviously on top of someone else’s body is just strange.

As the three Spirits arrive, one might hope for some visual invention, but with all the tricks at his disposal, Zemeckis can’t seem to find the imagination to utilize them to best advantage. One of the reasons given as to why he wanted to make the film was to realise the Ghost Of Christmas Past as the candle flame character he is described as by Dickens, but the reality is that it looks like what it is: a mo-capped head covered in flames rather than a face made of flame. Carrey brings an otherworldly Irish lilt to the voice, and for a moment you might believe something special has come along, until you notice the Spirit has stupid little cartoon hands. Why aren’t the Ghost Of Christmas Past’s hands more flames? It seems a laziness on the part of the filmmakers that then had me questioning other design choices: there is basically no need for a flame to have a chin. Or a nose.

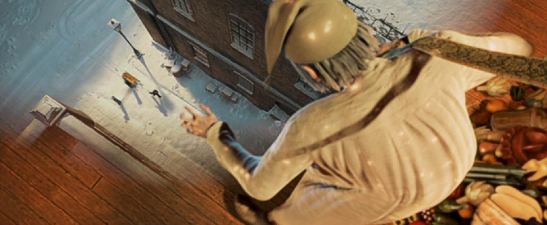

Much, much, much better is the entire middle act, where the Ghost Of Christmas Present dominates the film. This is Carrey again, naturally, but my word! Though again not terribly original in design, Christmas Present is easily the most successful result of the mo-cap process in A Christmas Carol, and is a real achievement and resounding surprise. By this point, I had resigned myself to simply enjoying the story rather than try and engage with the characters, but Carrey’s sheer exuberance, dialled up even more than usual, shines through, with real acting in his eyes! Perhaps it’s the joviality of the character, but Christmas Present storms into the movie and lifts it to another level and, if anything, it’s worth seeing A Christmas Carol for these scenes alone. The constant whirls around London between ghostly visits can be tiring, but this one, seen through the floorboards of Scrooge’s house, is uniquely conceived and brilliantly executed; a 3D sequence that works just as well and has the same dizzying impact in 2D.

The Ghost Of Christmas Present is really good, and it’s another frustrating aspect of the movie that begs, why can’t the other characters be given the same amount of detail and all be this great? If it’s time and money that need to be spent on achieving the remarkable results Carrey and the animators accomplish with the Christmas Present character, then this is precisely where Zemeckis’ future motion-captured endeavors need to be focused. My fear is that his next such film, an on-off-on (but pointless either way) remake of Yellow Submarine, would try and ostensibly resurrect the band circa 1968, but if ImageMovers Digital (now supposedly unsupported by Disney and apparently free from its Sony Imageworks association, going by their Hewlett-Packard endorsement and IMD retaining the copyright on this film) can get close again to what they’ve captured with Christmas Present, it could offer some hope.

A great deal of the genuine Christmas spirit throughout the film comes from long-time Zemeckis composer Alan Silvestri, who fills his score with traditional Christmas carols but never over emphasizes them, choosing instead to pick a phrase or two only and weave them into his original music. It has a wonderful effect of serving the film with much more magic than it might have, the mixture of deep orchestral arrangements and choirs bringing a real joy to Scrooge’s world and carrying him and the characters through their journey. A particular moment where all the elements come together grippingly is a nightmarish scene towards the end of the Christmas Present sequence, where the score and excellent lighting both go some way to really making the moment something you can’t peel your eyes away from, even if the video game camera moves and the two child sprites are to over the top.

A Christmas Carol is certainly the best of Zemeckis’ three (and a half, if you count the executive produced Monster House) mo-capped tryouts so far, despite the many shortcomings still inherent in the method (Simon Wells’ ImageMovers-produced adaptation of Berkeley Breathed’s Mars Needs Moms comes next year). They say “the eyes have it”, but that unfortunately that’s where mo-cap still falters and is the biggest hurdle for the process to jump. Every so often the older Scrooge looks too young, especially around the eyes, though I’ll be charitable and suggest this could be an intentional effort to express the good that remains inside him. But the Ghost Of Christmas Present somehow manages to fully overcome this difficulty – whatever it is they were doing differently I don’t know, but he just works, and they need to pursue this angle further if mo-cap is to remain a viable animation medium.

All of which leads to my being 50/50 split over A Christmas Carol. Because, Ghost Of Christmas Present and Scrooge at certain times apart, the motion-capture on show here is just still too clunky to be taken as an authentic alternative (though I await with great interest the WETA result of Spielberg and Jackson’s mo-capped but stylised Tintin movies). Even someone I saw the film with in theatrical release, who hadn’t been aware it was a mo-cap film, asked why the characters looked “funny and plasticky” and thought it was down to bad make-up. However, on the flip side, we both did still enjoy the various elements, namely Carrey’s performance, Silvestri’s score and the good old, basic story; the film certainly has an entertainment value. But, then again, did we really need another version of Dickens’ tale?

Cinematic interpretations of A Christmas Carol are almost as old as cinema itself, and particularly notable are Seymour Hicks’ first talkie version in 1935, Sim’s 1951 edition, Mr Magoo’s 1962 special, Albert Finney’s 1970 musical, Richard Williams’ 1971 animation (again with Sim), Mickey Mouse’s take in 1983 and, of course, The Muppets’ on fine form in 1992. That’s not to mention the huge number of television productions over the years, and it was only in 2001 that we had the last animated (but very dire) feature, with the voices of Kate Winslet and Nicholas Cage. What does Zemeckis’ bring new to the table? The answer is, inevitably, very little, and while the film is highly engaging at times, one can’t help but feel an opportunity for some more originality has been squandered in the attempt to pair “Zemeckis” and “Christmas” together again after The Polar Express.

For all the new technology on show, it ultimately doesn’t help this Carol be anything the others were not, and although there is periodically much to enjoy, it’s essentially very traditional, with a visually obvious, and thus visually boring, approach. So while Carrey and Zemeckis’ A Christmas Carol doesn’t quite raise a cheer of “ho-ho-ho”, it’s a case of not being so much of an “oh-no-no” either. But The Muppets did it better.

Is This Thing Loaded?

Notable for being Disney’s first Blu-ray 3D home video release, A Christmas Carol comes configured in multiple formats, the flagship set containing a BD-3D disc, the regular high-definition BD, a standard DVD and a Digital Copy file for portable device play, which truly stretches the gamut in the ways you can view the film, from the big-screen multi-dimensional experience to a tiny thumbnail image. For those (many) of you for which 3D isn’t an option and a digital file pointless, Disney has done the right thing and also provided a lower-cost Blu-ray + DVD edition, which is what is under scrutiny here, losing only a 3D-enhanced featurette, Mr Scrooge’s Wild Ride, from the 3D disc along the way in terms of added content.

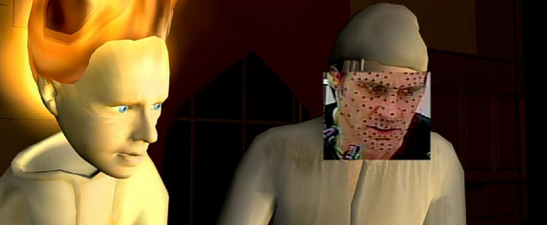

On the non-3D, regular Blu-ray Disc itself (in both sets), easily the best and most welcome supplement is the feature-length Behind The Carol: The Full Motion-Capture Experience (again forgoing the over-bloated performance capture moniker) bonus. Although it shares similarities with Disney’s regular visual commentary Cine-Explore features, there’s a good reason it doesn’t use the name, since this is something slightly different, though no less interesting: the complete motion capture footage shot of all the actors for their scenes playing out in a smaller window throughout the film, with an optional commentary from Zemeckis, though why one would switch this feature on without the commentary is a mystery, since so much refers to the other.

Even better, the mo-cap picture-in-picture is able to be magnified to full screen in order to look more closely at the technique, though Zemeckis’ insistence that mo-cap provides animation with more nuance than keyframe animators are able to give their characters will likely open up that heated debate all over again! However, since I loved Zemeckis’ work so much up until he started down the path to the uncanny valley, I am always intrigued as to why he continues to chase for the life-like perfection in this process (though not as intrigued as to why he can’t see the differences in his unconvincing approach versus the phenomenal work that regularly emerges from WETA Digital).

As such, I was more than happy to sit in The Volume (ugh…) for the duration of the film, to see if there were any clues, but while it’s interesting to see Carrey, Hoskins and company in their mo-cap outfits running through their performances, there’s a distinct separation from the process. The footage is not particularly close to the final camera results sans the “digital make-up” that you might expect, but actual on-“set” material that shows everything that was going on during the shooting. That’s all well and good – great at times, in fact – but I’d have liked to have seen “more” of what went into the creation of those shots, such as the rehearsal beforehand, Zemeckis speaking with Carrey over creative choices, or alternate takes.

Often, the picture-in-picture window offers two views of the same shot from different angles, but instead of split-screening these so as to become too small in the window, perhaps it would have been cool to pull up a second window for those moments? Certainly the fact that when we switch to the mo-cap footage full screen we lose the final CG rendered result is a shame, since it might have been nice to literally switch between them, reducing the finished film to the smaller window to keep track of both. The footage looks to have been shot in standard definition, or a lower resolution HD format, but appears to have been upscaled here and although there’s a lot of composite chroma noise, has obviously been primarily designed to play in the smaller window, though it looks as good as it needs to when blown-up, which is a nice touch.

Also, a note of kudos should be relayed to the actors for all allowing themselves to be seen in their mo-cap get-ups, which aren’t flattering to say the least, and to Zemeckis for airing his point of view. Ultimately, although Behind The Carol doesn’t really bring about a new appreciation for the mo-cap technique, and even if some of his comments are questionable in their assumptions and will no-doubt infuriate some animation artists as to what he believes is achievable in pure animation as well as insisting that his preferred approach should be accepted as such an animation process – while also bemoaning the lack of credit to his live actors – there’s still the pleasure to hear the director talk about his actual filmmaking methods, when he breaks away from the mo-cap talk and speaks in terms of camera framing, staging and editing, which is the real highlight here.

Adding a bit of meat to the bones of the mo-cap footage, Capturing Dickens: A Novel Retelling (bypassing the fact that Dickens’ story was a serialized novella, not a novel) takes what we have learned in the feature commentary track and gives us a potted version that general audiences will find more interesting. The pre-requisite talking heads (Zemeckis, Carrey and various cast and crew) run us through the creative process, from the faithful translation from Dickens to the motion-capture itself, though there’s precious little on anything else, such as the concept and development work (A Christmas Carol went through a full production design before Doug Chiang came aboard) or the animation cleanup. And through no fault of her own (I hope), narrator Jacquie Barnbrook has apparently been asked to pop up throughout the 15-minute featurette in an overly enthusiastic manner, presumably to bring a little life to what could be seen as a weird production process, but really she’s just annoying (maybe even obnoxious?) and not in keeping with the film or its otherwise classical approach.

The Countdown To Christmas Interactive Calendar offers up some Christmas cheer by way of what the title suggests: a static screen “calendar” that, when each day in December is opened up, presents a brief simply animated “Christmas treat” video clip, anything from a few bars from a music box to a magically completed jigsaw puzzle, although one or two can be quite odd choices. I hope the producers of the disc don’t expect us all to keep inserting it every morning throughout December until Christmas Day on the 25th, so you’ll probably do what I did, which was to sample a few days beforehand. A nice touch, though, is that after each window has been opened a new decoration will adorn the street scene depicted, and don’t try to skip ahead: select a future date and Scrooge will “Bah, humbug!” you into submission, about the only link this otherwise has to the film itself.

Going back to the motion-capture stage, On Set With Sammi: A Kid’s Eye View joins young Cratchit actor Sammi Hanratty for an “anything but average” day. She’s actually a nice kid and not your typical precocious Hollywood brat, and spending these brief couple of minutes with her is fun, not least because it shows a little more of the setup outside the mo-cap stage: short but sweet. A series of six Deleted Scenes are individually available or as an eight minute Play All option with an intro from Zemeckis, who explains that none of these sequences are completed. None add anything substantial from a story point of view, but what’s interesting is to see the pre-viz style early renders before the facial animation data has been added, though the actors’ faces have been inserted in and matched to their movements to give an idea of their intended performances.

Lastly, a frankly bizarre advertising short, Discover Blu-ray 3D with Timon & Pumbaa, suggests it’s a new cartoon what with the opening Disney logo playing out in full, but while there does appear to be new animation featuring The Lion King’s comedic pair, it’s basically just a commercial, with a Goofy-like How To… narrator harping on about the benefits of three dimensions in the home. The animation is okay in spots, but mostly limited, and without the third dimension in place, some of the gags don’t work, and it resorts to playing out with promo clips for upcoming Disney 3D programming (including, oddly, A Christmas Carol). Ernie Sabella returns as Pumbaa but Nathan Lane was obviously too busy to come back as Timon, though it probably doesn’t matter as they’re only on screen for roughly less than half of the overall four minute runtime, which itself includes a minute and a half of logos.

The standard definition DVD (the same one as being sold separately) naturally includes the main feature, as well as the same Sneak Peeks of Bambi: Diamond Edition, the upgraded Tron: Legacy and the downgraded The Sorcerer’s Apprentice along with Disney Blu-ray and others available from their own menu option. Naturally the Motion-Capture Experience and Interactive Calendar aren’t included for technical reasons (even though there’s no real reason why they couldn’t be converted, the mo-cap footage using DVD’s angle feature), and why the audio commentary hasn’t at least been pulled over is a mystery, but the two featurettes (Capturing Dickens, On Set With Sammi) do appear, as well as three Deleted Scenes and Disney’s BD and 3D commercial spots. As mentioned before, there’s no Digital Copy in this BD/DVD combo edition.

Case Study:

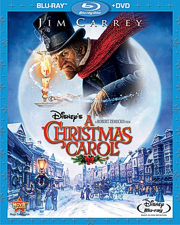

Despite the fact that this slimline cased set doesn’t contain all the 3D bells and whistles in the bigger four-disc set (along with the nice and Christmassy red border trim on the front), we should actually be much more pleased with this BD and DVD combo’s cover since it uses the much more evocative theatrical poster artwork of the brilliantly curmudgeonly Scrooge backlit by the full moon over the snowy streets of olde-world London, which is just about the most singular signature image any version of A Christmas Carol could ever hope for.

Replicated on both the shiny slipcover and the sleeve art underneath, I’m not sure the description of the film as a “Disney classic” rings quite true, but the art does what it does in the now regular Disney-designed fashion. The disc art misses out a trick of using the moon sphere as the circle edge for the label print, also sticking to Disney’s half-and-half Blu disc design, while the DVD is as dull and gray as they come. Inserts with the Movie Rewards code and promos for Blu-ray 3D and other upcoming releases (including much nicer Fantasia 2-Movie Collection art) are included.

Ink And Paint:

With a film created at the kinds of resolutions to make a three-dimensional appearance work, the translation to Blu-ray was never going to be an issue. We can’t say how the 3D format will work in the home, since that disc isn’t included in the more general-use BD+DVD combo pack, but the film’s 2.40:1 “flat” theatrical ratio has been preserved here and looks suitably spotless.

In fact, for all the talk of adding dimension to these kinds of films, given a solid image presentation like this and a well calibrated screen, I have to say that there’s never any question of real depth in the image, which is certainly enough 3D for me and several guests watching at the same time without the need for each of us to lock ourselves away under annoying glasses. Less than twelve months old, this is a state of the art image that shows off (and unfortunately reveals) all the good and bad about the motion-capture process. There’s some great demo material in here somewhere, but best kept to the convincing Ghost Of Christmas Present scenes.

Scratch Tracks:

Again, coming up with superlatives to describe the solid state of the art soundtracks that we are treated to from modern blockbusters in uncompressed DTS mixes on Blu-ray Disc is becoming more and more tricky. In short, this is an aural delicacy, with the fantastic voices and the very essence of Christmas wrapped up in Silvestri’s score providing the spirit the visuals can sometimes lack. Indeed, in those moments, it might be worth closing your eyes and shutting out the visuals just to soak up the atmosphere from the music and vocal performances, so good as they are, reproduced with exceptional fidelity on both the HD and SD discs. Dolby Digital dubs and subs in English, French and Spanish are also optionally bundled in.

Final Cut:

A Christmas Carol’s disc extras open up the mo-cap process for those interested, but it serves us precious little else other than that: the supplements’ main role is to show and attempt to validate mo-cap as a creative animation process, but if anything it only makes everything look even more like it’s too dependent on the computer. Additional looks at production design, props, costumes and the multitude of any other physical elements that play a part would have been welcome to see, since it’s not all just down to those body hugging capture suits and Zemeckis’ (admittedly very cool) computerised real-time camera.

One gets the feeling that, for all that is shown here, there’s an awful lot we’re still not seeing and, while the likes of Avatar continue to steal thunder away from endeavors like these, ImageMovers still has a way to go yet before they can match some of the best work coming from other effects houses. The best of Zemeckis’ explorations into motion-capture territory, the film isn’t always successful in terms of the technology, but the classic story, spirited (sorry!) performances and especially Silvestri’s pure essence of Christmas score all help to pull the whole thing together, though whether this version of A Christmas Carol turns out to be a Christmas classic will be down to Christmases yet to come…

| ||

|