If you do not know who Otto Messmer is, you are not yet a cartoon connoisseur; and if you wish to be, it is essential that you get thee to a DVD outlet and find some old-style Felix The Cat. Messmer was the animator behind Felix, and it was his talent that made Felix the hit that he was back in the Roaring Twenties. Felix was a marketing phenomenon years before Mickey Mouse made the scene, and for a time was the most popular cartoon character in the world. And, if you think you know Felix from his television cartoons, well, you just do not yet know the whole story.

As John Canemaker noted in his landmark book on Felix, Felix’s producer Pat Sullivan took the credit for Felix for years. He may have felt justified, since it was his business and promotional skills that aided Felix’s success around the world. However, all the business skills possible would not have mattered if Felix’s cartoons were no good. On the contrary, Felix The Cat was immediately recognized as a landmark character in animation history, since that is exactly what he was: a character. Prior to Felix, animated characters were generally created simply as a means of putting over a gag. It was not necessary for them to have personalities, as the novelty of moving pictures telling simple jokes seemed to be enough to entertain early audiences.

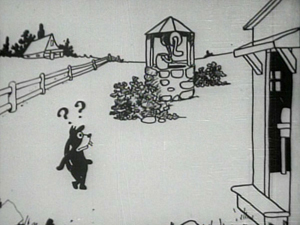

That all changed with Felix, who clearly was able to formulate thoughts, ideas, and emotions. The little guy had spunk, and was able to solve his problems in a clever way. The films themselves were also clever and whimsical, shining with a creative spark that other cartoons of that era could not match. The cartoons are admittedly crude by today’s standards, but the modern age had to get its start from somewhere, after all. When compared to such contemporary fare as Paul Terry’s Aesop’s Fables series or Colonel Heeza Liar, Felix was a revelation.

Messmer had seen Winsor McCay’s brilliant animated shorts in the 1910’s, and like many had been impressed with their fluidity and craftsmanship. In many ways, McCay’s works were about two decades ahead of their time. Still, McCay only ever produced a handful of films, which were often confined to his vaudeville shows, and he did not include a recurring character (although fragments exist of a Gertie The Dinosaur follow-up). Nevertheless, Messmer was inspired by the magic of animation even as he was selling cartoons and humorous poems to publishers. Although successful in those pursuits, he kept an interest in filmmaking and signed a 1915 agreement with Jack Cohn (future co-founder of Columbia Pictures) at the Universal Film Manufacturing Company studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey. His original intention there was to become a scene-painter; but his drawing samples, including some rudimentary animation work, led Cohn to sign him up to create an animated test film for the Universal newsreel.

Unfortunately, Messmer did not actually know how to create animated cartoons, although he had some idea. He had picked up some tips from listening to McCay, but did not know of such innovations as Bray’s cel method, nor Barre’s peg system. Still, using an animation table his father built him, some cardboard sheets, and his own ingenuity, he crafted a film featuring a character named “Motor Mat”. It was well received enough by Cohn, but was never released theatrically. It did, however, result in Cohn introducing Messmer to another animator who used the studio facilities, Pat Sullivan, as well as renowned cartoonist Hy Mayer, who also shot humorous film shorts but did not animate.

Both gentlemen offered Messmer work, and Messmer chose the better-known Mayer. A successful theatrical animated short featuring Teddy Roosevelt resulted, where Messmer essentially did the “in-between” drawings to match Mayer’s key poses. After that job, though, Messmer was again unemployed and decided to meet with Pat Sullivan.

Sullivan was originally Pat O’Sullivan, an Australian who got a weak start in his native country before moving to London for a similarly unsuccessful stint, before landing in New York on a mule boat. There, he hooked up for a while with the McClure Newspaper Syndicate where he was an assistant to William F. Marriner, ghosting his Sambo strip until it was cancelled several months following Marriner’s suicide. Meanwhile, Sullivan developed an interest in animation, finding a stint as a worker in Raoul Barre’s studio before getting fired and opening up his own studio in 1915. He used Universal’s facilities to shoot animated advertisements, a cartoon rip-off of Sambo called Sammy Johnsin, and a number of authorized shorts featuring an animated Charlie Chaplin.

By this time, there were numerous animation studios already operating in the New York/New Jersey area, working in assembly line fashion to crank out what were mainly unsophisticated cartoons, but Messmer was pleased for the opportunity to work at one of these studios. He was quite a find for Sullivan, it turned out, as Messmer’s quiet and passive demeanor allowed Sullivan to ably make use of him. Sullivan, about seven years older than the meek and modest Messmer, had a much more aggressive personality, as well as the sophistication that comes from travel and a variety of experiences both positive and negative. One might say that both men were flawed, but whereas Sullivan’s flaws mainly benefited himself and made him unlikable once you got to know him, Messmer’s flaws benefited others but made him well regarded in many ways.

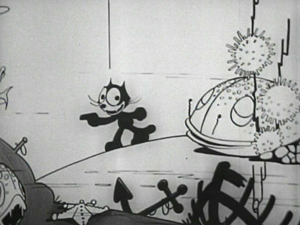

Both Sullivan and Messmer had qualities that the other admired. Messmer, apparently always seeing the good in others and ignoring Sullivan’s problems with alcoholism, appreciated Sullivan’s self-made nature and worldliness, while Sullivan liked the fact that Messmer already had some animation experience and— it turned out— a natural propensity towards exploiting the possibilities of the new art form. It took just a few cartoons before it was clear that Messmer brought something special to his work. Most animators at Sullivan’s studio and others were interested in bringing life to drawings— but Messmer liked to explore what made cartoons different than live action. Messmer knew that there was more magic to be had in cartoons than simply making characters move. Animation lent itself to so much more— transformation effects (often referred to as metamorphosis), use of inanimate objects coming to life, and a variety of impossible tricks that could be best described as FUN.

Messmer worked on a number of projects for the studio, including some Chaplins, and a two-reeler that accompanied Universal’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The Messmer-Sullivan teaming would break up for a bit, though, due to a statutory rape charge against Sullivan that saw him serve nine months in jail, and Messmer’s being drafted. (Sullivan’s “felon” status kept him from being drafted.) When Messmer returned from the War, he found that Sullivan had re-opened his studio and was open for business. Sullivan had to work hard to build it up, but it had reached some level of success again and he was glad to have Messmer lend a hand.

One of Messmer’s first new assignments would be to create a short cartoon to fill out a program for the Paramount Screen Magazine as a favor to animation producer Earl Hurd in 1919. Messmer, working on a tight deadline, decided on an all-black cat to simplify things for the inking staff. He produced a piece entitled Feline Follies, which proved to be popular with audiences and therefore Paramount. More orders came in, and the cat— named Felix by his third short after starting out as “Master Tom”— became a sensation. “Felix” was a play on words between “feline” and “felicity”, suggesting a “lucky cat”. Felix tickled audiences with his plucky nature, his metamorphosizing tail, and pantomime performance that was reminiscent of Chaplin. As it turned out, Felix was just what audiences were looking for in an animated cartoon character. At last, people could see a fellow who could do what human performers could not, and best of all Felix had personality. One could see Felix think his way out of a problem, and the delight he took with his successes.

And did he enjoy success! By March 1920, Sullivan had signed a two-year contract with Famous Players-Lasky Corporation to make cartoons for Paramount Magazine. With the new deal for Felix, Hal Walker was hired as Messmer’s assistant, keeping that position for nearly ten years. Sullivan still got all the praise, though, routinely credited in trade articles for being the animator and creator of Felix. Of course, the public was not so concerned with such details, and was mostly interested in seeing more of Felix at the cinema. And, after all, Sullivan was the producer of the films, just as Walt Disney produced but did not actually animate Mickey Mouse. Of course, the difference was that Walt did have a lot of input and control with all of his films, and did share credit with those who deserved it. Mickey Mouse animator Ub Iwerks’ name can even be seen on some early Walt Disney posters.

Despite the apparent success of Felix, the president of Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, Adolph Zukor, felt that Paramount Screen Magazine was too costly an enterprise and decided to end it. This was quite a problem for Sullivan, as it was Famous Players-Lasky that owned the Felix copyright, leaving Sullivan out in the cold. Sullivan went to Zukor’s office, drunk as usual, and pleaded for Felix’s copyright. Legend has it that Sullivan used the unusual negotiating tactic of urinating on Zukor’s desk, but whatever occurred in that office worked. Felix would belong to Sullivan.

Sullivan tried to sell Warner Brothers on the idea of taking over distribution of Felix, but they declined. However, H.M. Warner’s executive secretary Margaret Winkler was interested, and with Warner’s blessing she signed a contract with Sullivan herself in December 1921. This was another significant step for Felix, as Winkler recognized that despite their popularity, the Felix cartoons would need to be better in order to compete in the current marketplace. She demanded better stories, animation, and production values, and Sullivan and Messmer responded. Messmer had done a pilot film called Felix Saves The Day, which mixed animation with live action and showed signs of improvement already. It ended up being the first picture released in the Winkler package in early 1922, for which Winkler skillfully found solid distribution and promotion.

Felix’s popularity took off, resulting in a wide variety of licensed products that proved to be easy income for Sullivan. Felix became the first animated cartoon character, aside from newspaper strip properties, to become a doll or to be exploited so widely in other ways. All was not rosy between Sullivan and Winkler, however, as Sullivan felt that she tried to exert too much creative control, and she had a bad habit of putting out press releases that named Felix as “her” cartoons. The irony here is obvious, as Sullivan had only legal ownership of the character, but the unsung Otto Messmer was the real talent behind the cartoons themselves. Nevertheless, a second year agreement was made between Winkler and Sullivan, involving a bit more money per short, and a lot more of them (one every two weeks). Sullivan’s studio grew to match the demand, and moved altogether in 1923. Messmer gained permission to use other animators on his films, beginning with Bill Nolan. Nolan made the crucial decision to redesign Felix as rounder and frankly more appealing. Messmer approved, and the new cuddlier Felix was established by 1924.

By this time, Felix also had his own newspaper Sunday comic strip, which had begun in August of 1923. Just as in the cartoons themselves, Sullivan’s name appeared on the strip, but it was written and drawn by Messmer. It lasted until 1943, although it was never considered to be nearly as popular as the animated cartoons.

The same month that the Sunday strip appeared, controversy arose between partners Sullivan and Winkler. Winkler and her fiancé Charles B. Mintz asserted that they had an option for more Felix cartoons at the previous price, while Sullivan wanted a more lucrative contract and to make longer cartoons. Sullivan signed a new deal with distributor Joe Brandt, but the Mintzes managed to scare him off and he cancelled the deal with Sullivan. Lengthy negotiations eventually resulted in a new contract between Sullivan and the Mintzes. That would be the final one, however, as Sullivan became unhappy with how Felix was being edited and merchandised by its European distributor, Pathé (with whom Winkler had made the deal). He was also somewhat disgusted by the appearance of a cat in Disney’s Alice cartoons that looked and acted too much like Felix. This was particularly troublesome to Sullivan, since Winkler and Mintz also distributed the Alice shorts! (Apparently, Mintz had encouraged the Disney artists to ape Felix, over Walt’s objections.)

As the Winkler/Mintz deal was about to expire, Sullivan’s longtime lawyer Harry Kopp formed Bijou Films, under which all future Felix films would be produced. Kopp wasted no time in signing with Ideal Film Company Limited, for the impressive sum of $5,000 for each of 24 Felix cartoons to be shown in England. Kopp also signed a deal with the Educational Films Corporation of America for rights to the films in the States, which was followed by a lawsuit launched and lost by Winkler and Mintz in 1925.

Sullivan celebrated his good fortune with a months-long trip to Europe, including promotional stops, while Messmer and his staff cranked out some of their best Felix cartoons. The press, seemingly eager to trumpet any appearance by Felix’s “creator” ignored the fact that Sullivan was nowhere near his studio for months at a time while the cartoons were being created. The animators always knew who the true genius of the outfit was, though. Many interviews over the years have repeatedly seen animation staff from the Sullivan studio acknowledge Messmer’s role in crafting each and every Felix picture, albeit via an eventually large studio staff.

Interestingly, the Felix cartoons were done contrary to later methods. With the Felix shorts, background cels were placed on top of characters drawn on paper, which naturally required careful planning to keep characters from crossing horizon lines and appearing to float away unintentionally.

Felix’s popularity continued to expand. Felix The Cat merchandise was all over both the United States and England— dolls, banks, toys, books, music sheets, cigars, clothing, spoons, and countless other items. Felix saw a King Features daily newspaper comic strip begin in May 1927. Jack Bogle initially drew the dailies, while Messmer continued with the already established Sunday page.

As Felix continued to be a huge success in the mid-Twenties, he became a true icon recognized around the world. It seemed like nothing could halt his popularity… and then Walt Disney came along with Steamboat Willie. Although there had been a few films from Max Fleischer and Paul Terry that used sound, Disney did it best and most famously with his first-released Mickey Mouse short. Clearly, fully synchronized sound cartoons would be the wave of the future. Disney felt he was about to hit it big, and while in New York following the launch of Steamboat Willie, Walt looked for other animators to join him. (He had lost much of his staff to Mintz in the Oswald incident, where Mintz took Walt’s creation away from him, as well as his animators.) He visited, among others, Otto Messmer, who turned Walt down since Messmer’s roots were in New York and he could not see himself moving to California. Of course, Otto was also thinking of his loyalty to Sullivan, as well as the seemingly unstoppable success of Felix.

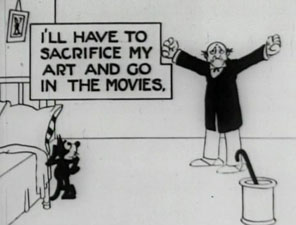

If only Sullivan was as forward thinking as Disney, Felix may have survived longer than he did. Felix remained popular still in 1928, and was famously used as the image for NBC’s first television broadcast that year. However, Education chose to not renew their contract with Sullivan after the 1928-29 period, largely because Sullivan resisted adding sound to the Felix cartoons, more out of stubbornness than as an artistic choice. He relented later, though, in order to sign a contract with Jacques Kopfstein to distribute the Felix pictures through Copley Pictures Corporation. It was a failed venture, unfortunately, as the sound synchronization was all done after the animation, with sloppy and uninteresting results. The few Felix sound films flopped. Felix was out of the motion picture biz by 1931. Just like that, it was over.

Things deteriorated rapidly then for Sullivan, the once-famous “creator” of Felix the Cat. He sunk further into alcoholism. His wife died either accidentally or by suicide in 1932. Shortly thereafter, his mental health noticeably waned, whether due to alcoholism, depression, or advanced syphilis. He had few to no close friends, after a lifetime of shameless self-promotion, immodesty, alcoholism, and questionable morals. He died in February 1933 of alcoholism and pneumonia, at the age of 48.

In the aftermath of Sullivan’s death, his lawyer Kopp had to detangle the question of ownership of the copyright, especially pertaining to the Felix comic strip. It was an important issue, as Sullivan still had heirs who relied on some income from Felix’s licensing, which would dry up quickly if Felix disappeared from newspapers as well as the cinema. Messmer reported to Kopp that Sullivan had promised him the rights to Felix upon his death, but knew that he had no evidence of this, and simply requested that he be guaranteed a place on the comic strip; he also sued the Sullivan estate for two weeks’ salary owed to him. As a result of negotiations between all parties, Messmer got to continue drawing Felix for the papers, King Features kept their rights to do the strip, and the estate kept all other rights to Felix. Eventually in 1950, Sullivan’s nephew, also named Pat Sullivan (having likewise dropped the “O” from his name, apparently), took over Felix The Cat Productions.

Kopp also tied up many other loose ends— ends that had been left due to Sullivan’s habit of entering oral agreements for merchandising without telling his lawyer (and thus saving lawyer’s fees). The difficulty of communicating with the heirs in Australia, as well as the usual legal complications, prevented the Sullivan studio from continuing even when other offers eventually came in to distribute more Felix.

This changed finally in 1935 when Amedee Van Beuren approached Messmer about resuscitating Felix for his Van Beuren Studio, which was in desperate need of a star character. For uncertain reasons, Messmer turned down the chance to be involved, and Van Beuren proceeded without him. After getting the rights from the Sullivan estate, Van Beuren assigned Burt Gillette of The Three Little Pigs fame to direct three Technicolor Felix shorts under the Rainbow Parades banner. Those films were polished tributes to Disney’s extravagant shorts, but the results were sadly uninteresting due to diminished characterization of Felix and awkward direction. Of course, Felix was never really meant to be used in lavish, full-color, brightly scored cartoons. He was a simple cat who seemed out of place in a technically sophisticated picture. A fourth Felix Rainbow Parade died along with Van Beuren’s RKO distribution deal, which resulted in the folding of the studio.

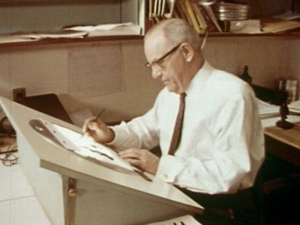

Messmer, meanwhile, contentedly worked on the Sunday strip until it ended in 1943 (although he would come to be the artist and writer of the daily strip, which lasted until 1967.) He also switched over to writing and drawing the Felix comic book in an eleven-year stretch for Dell Publishing. As well, he took a position with an advertising display company, from 1937 to his retirement in1973, which was a perfect match to his talents and working methods. This allowed little time for theatrical animation, although he did do some work for Famous Studios in 1944-45. He also did a commissioned Felix work for Walt Disney’s Disneyland television show episode The Story of the Animated Drawing, where Walt subtly hinted at Messmer’s role in the creation of Felix (being restrained somewhat by the contract he signed with Felix The Cat Productions, Inc.). And yes, that episode is featured in the DVD set Walt Disney Treasures: Behind the Scenes at the Disney Studios, so take a look at it again now that you are more educated about Felix and Otto Messmer. On the show, a photo is shown of Messmer, while Walt describes him as Sullivan’s “collaborator” who drew the cartoons.

As Messmer’s workload became too much to handle, he sought out help from Jim Tyer and Joe Oriolo (a former Fleischer animator). Oriolo eventually took over all the Felix drawing work, and in 1958 he and young Pat Sullivan became two of the four directors of Felix The Cat Creations, a wholly owned subsidiary of Felix The Cat Productions, Inc. The purpose of the new subsidiary was to produce new Felix films for television. 260 four-minute Felix films were produced, beginning in 1959, utilizing the voice talents of Jack Mercer. It was on this show that Felix acquired his “magic bag”, and a supporting cast. It lasted for years in syndication and is still well remembered by baby boomers.

Felix The Cat Creations was dissolved in 1971, while Oriolo became a director of Felix The Cat Productions, Inc., and later became its President when Pat Sullivan died. It was he (to be succeeded later by his son Don) who worked hard to keep Felix a viable merchandising character, and also he who championed Messmer as the true creator of Felix. Further acknowledgement of Messmer would came later at Montreal’s EXPO ’67, magazine articles, and with conferences and television shows appearances in the 1960s and 70s. Messmer passed away in 1983, and his obituary did indeed credit him with Felix’s creation.

Another Felix television series came out in 1982, this time a half-hour live action series. (I found mention of this in a couple of places, but cannot recall the show, nor could I find more information on it aside from its theme song.) He returned to his properly animated form in Felix The Cat: The Movie, which was written and produced by Joe’s son Don Oriolo and came out in 1991. 1995 saw a new cartoon show, The Twisted Adventures Of Felix The Cat, courtesy of Film Roman. Another feature called Felix The Cat Saves Christmas came out on DVD in 2004, and a Baby Felix show was also produced.

Through all this time, Felix has been consistently in the public eye thanks largely to the Oriolos, in the form of merchandising as well as new cartoon projects. His face still appears on numerous notepads, clocks, cookie jars, and the like. As recently as the year 2003, fifty new deals were made to license the character! I wonder if most folks these days even know where Felix The Cat started out, though. He is iconic now beyond his animation roots. For us cartoon connoisseurs, however, we will always remember that Felix started out as a revolutionary figure in animated films by the uniquely talented Otto Messmer, films that can still be enjoyed and studied on DVD.

Acknowledgements:

Felix: The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker— if you enjoyed this article at all, you MUST buy this book! It is a wonderful treasure trove of info on Felix and the men behind him, filled with rare photos and artwork. Most of my information came from this book, but there is so much more there to enjoy!

Felix The Cat’s Official site