Please, welcome… The King of Cute! Well, animator Dave Pruiksma, of course! A title that seems particularly appropriate in that over the past 20 years Pruiksma has been cast on some of the more adorable characters to come out of the Disney menagerie.

Please, welcome… The King of Cute! Well, animator Dave Pruiksma, of course! A title that seems particularly appropriate in that over the past 20 years Pruiksma has been cast on some of the more adorable characters to come out of the Disney menagerie.

Dave Pruiksma had the usual interest in animation from an early age. Growing up in the Virginia suburbs, just minutes from the heart of Washington D.C., he was first influenced by early television cartoons, but remembers being really “blown away” by the 1964 television broadcast of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland. It was then that Pruiksma decided what his life’s vocation would be. Dave drew constantly through school, eventually making his own series of Super-8 films. Upon graduating from High School in 1975 he was accepted into the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn N.Y. where he received a very solid formal Art and Film training for two years.

He was one of a handful of students selected to work on a theatrical film project (based on a Bertholt Brecht play) that was being done at the school by veteran puppet animator Lou Bunin. Still, Dave felt that he wasn’t getting the training he needed to become a professional animator. His instructors recognized his ability and suggested a move to Los Angeles, where the animation industry was based. He applied to California Institute of the Arts and was accepted into their Character Animation program starting in the Fall of 1979.

At Cal-Arts, Pruiksma applied the foundation he had learned at Pratt to Disney style character animation under the instruction of renowned Disney artists T. Hee, Jack Hannah, Elmer Plummer and Ken O’Connor. From 1979 to 1981 he produced two short animated films, learning everything about animated film production from design to sound mixing. He even performed voices for other students’ films.

Hired at Walt Disney Feature Animation in the summer of 1981 as an inbetweener on Mickey’s Christmas Carol after only two years at CalArts, David worked with top animator Ed Gombert bringing Ratty and Moley (from Walt Disney’s The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad) back to the screen after their 35-year absence. He later went on to do assistant work and small snippets of animation on the character of Gurgi for The Black Cauldron. After this, he joined directing animator Mark Henn in bringing the lovable, rotund Dr. Dawson character to life for The Great Mouse Detective.

After a brief stint working on the feature-length production, The Chipmunk Adventure (again focusing on the more appealing Chipmunk characters), Pruiksma returned to Disney Feature Animation to work on several characters for Oliver & Company, before animating some of the greatest characters of Disney’s animated features of the next decade.

Which makes him the perfect person to talk with about that movie and its importance within Disney’s animation revival during the 1990s!

Animated Views: What was exactly your assignment on Oliver & Company and how was the production of animation organized?

Dave Pruiksma: On Oliver and Company, my title was that of animator. As such, I was working independently on a number of the characters in the film, but mostly I went to Mark Henn for feedback and character direction. There were not really “Directing Animators” on that film as there were on later productions. Mike Gabriel was pretty instrumental in the overall look of the animal characters, though. In fact, it almost seemed like he was, officially or unofficially, directing animation on the film. I did a lot of scenes of Oliver, Jenny, Winston, Georgette and Tito, but I actually animated nearly every character in the picture at one point or another, throughout production.

AV: What was the challenge of animating Oliver? Was it difficult to animate a four-legged animal?

DP: No. Four Legged animals are really not much more difficult to animate than humans. It’s just a matter of getting used to the way an animal walks naturally and then imbuing that walk with personality. I think Mike Gabriel did a really successful job of that with Dodger. As for Oliver. The trick was to keep him appealing and sympathetic without going too far and making him cloying. So many cute characters move into that latter arena.

AV: Was Andreas Deja and Mike Gabriel’s design easy to animate?

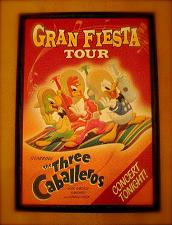

DP: A good design is always easier to animate than a poor design. Sadly, I see a lot more poor designs these days, particularly in CGI films, and this makes the animation less successful. A while ago, I worked on the characters from The Three Caballeros for Eric Goldberg. It was truly amazing, working with classic characters that were designed for appeal and animation. I took to it at once, it was a breeze. This current generation of designers could take a lesson by looking back at what has worked in the past and incorporating those principles in modern designs. The designs on Oliver & Company were, on the lower end, serviceable, and on the higher end, excellent.

AV: What are the Oliver scenes you worked on?

DP: Frankly, it is so long ago I don’t really remember them all anymore! I remember a lot of Jenny and Winston scenes. A lot of little Oliver. Some Georgette. And a Tito or two. Recently, I saw a little sequence I animated by myself at the end of the You and Me Together song, when Jenny and Oliver are getting ready for bed and through Winston turning out the light and shutting the door. I thought that section came out quite nicely, indeed.

AV: How did you work with Oliver‘s other animators to keep him cohesive throughout the film?

DP: I think I worked with Mark Henn on acting and whatnot, running my scenes by him for advice and guidance, but mostly I just presented them to George Scribner for approval. As I said before, there really wasn’t the structured Supervisor/Animator set up that was adopted later on. Things were a little more loose in those days and yet, the characters were all very consistent overall. At least I think they were.

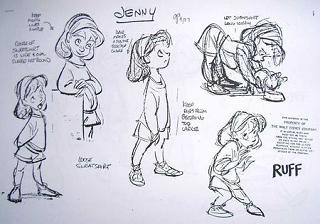

AV: Now on Jenny, what was the challenge of animating her? She was very much reminiscent of The Rescuers‘ Penny, wasn’t she?

DP: Jenny was not at all difficult to animate. And, yes, she was rather “Pennyesque” in appearance now that you mention it. I seem to recall, though, a lot of trouble coming up with a consensus on the design of her hair and clothing. Personally, I don’t really care for what we ended up with, but it worked and the film was successful and that is ultimately what is important. I would actually like to credit assistant animator Emily Juliano for her wonderful clean up work on a number of my Penny scenes. She did excellent work keeping appeal and warmth in the drawings and, for a young animator, that is always a blessing. As for approach to animation, I always approach the characters as if they were classic characters. Every character I am assigned to animate gets my undivided attention and respect. I have no levels of approach. For me, there is only off and on. No low or medium.

AV: How did you work with Glen Keane and Doug Krohn on Jenny, and with the other animators?

DP: As I recall, Glen focused more on the Fagan, Georgette and Sykes characters in the film and less on Jenny. Doug Krohn, Mark Henn, myself and a number of other animators focused on Jenny.

AV: It was a very difficult period for Disney animation, being moved to Glendale. Can you tell me about that atmosphere, the ambiance at the studio. What was it like to work there and not in Burbank?

DP: Difficult is rather an understatement, though accurate. It was, more aptly, an insult to the legacy of Disney Animation. The animation building was carefully designed and built for animation and housed the department for nearly 50 years at that time in 1985. I remember getting the memo about the move from the animation building as though it was yesterday. It was early in December of 1985 and the text of the memo rather matter of factly informed the department that it was being moved to a location somewhere in Glendale. The entire animation department was being unceremoniously evicted from it’s decades long home on the lot in the “ANIMATION” building to make way for plush offices for executives and stars like Bette Midler. Well, it was like a brick in the face to most people. We already all knew that the animation department was walking on shaky ground.

We had just gotten through months of insecurity as the hostile takeover of the company raged. And, once Eisner and the rest of the new management came in, they began scrutinizing the animation department and categorizing it as old and outdated and expensive. There was much discussion about ending the tradition with the release of The Black Cauldron. I say these things just to give you an idea of the mood on the lot at that time. I even wrote a little song about how we all felt to the tune of Oh What a Merry Christmas Day from Mickey’s Christmas Carol, which had recently been released. I called it, Oh What A Lousy Christmas Day and you can see the actual, type written text (no computers then) at the following link. I think that it pretty well sums up morale at that time and it was most popular in circulation around the department.

However, once we were moved, we all found that the Glendale facilities were not terrible by any means. Nothing like the studio animation building, mind you, but serviceable. Still, morale was low and each week and month seemed like our last. Rumors flew and unease was all around, but, being that we were all together and had a job to do (Basil of Baker Street was nearly half finished), we ploughed on, honing our craft and growing, artistically as we went. As the animation department grew, and the films became more and more successful, new warehouse buildings in the same Glendale Industrial park were purchased and renovated for different productions. We artists were then moved around from building to building, based upon which production we were assigned.

Feature Animation was promised a new building for the department would be built on the lot within two years of our departure, but that failed to happen until some years hence. Over time, anxieties about our future faded as we became more confident and successful and as Jeffery Katzenberg became more interested and involved in the department. Funny, I remember remarking to several people during that era, “Well, we may not have the most palatial environment in which to work, but I think we will always look back on these warehouses as the places where we made the best films of our generation.” Indeed, looking back now, I think that was a very accurate assessment and some of my happiest memories of production at the studio come from that time in those nondescript buildings in the Grand Central area of Glendale, CA.

AV: It is said that Frank & Ollie came on the production to help out in 1987. Did you meet them on that occasion?

DP: I don’t know if it is accurate to say that Frank and Ollie came in specifically to help out on Oliver. To be honest, Frank and Ollie were always around the animation department. They came in many times to give lectures and pep talks to the animation staff. But, I would not say that they actually worked on Oliver & Company. In fact, it was Eric Larson who remained at the studio, full time, to help train young animators until he was eventually run off by the executive staff. Of course, I have the utmost respect for all the animators that I have met that worked during the classic 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s animation. They were, for the most part, masters of the craft and helped to make me the animator I am today. Without their passing on of the gauntlet to we, the up and coming generation of animators, there might not have been a second golden era of production.

AV: How was it working with your director, George Scribner?

DP: George is a very talented artist and a hell of a nice guy. He was known by some as indecisive as a director, but I never had any trouble with him. You must also remember that this was a very difficult time in the history of Disney animation and Oliver & Company had a rather rough start. Story problems delayed production and, in fact, a good number of animators were laid off at the beginning of production so that these problems could be worked out before continuing animation. Voices were recast, songs re-written and more. A year passed before the problems were solved and then most of the artists that were laid off were called back to start into production exactly where they had left off. But, with all the upheaval, Oliver was released and became the highest grossing and most successful animated feature to that date.

AV: Now that Disney is celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Oliver & Company, how do you see the film now?

DP: I look back proudly on most of the animated films that I worked on in my long Disney career, even films that I think may have been, shall we say, less than stellar achievements in the art form. However, all the animated films had their place and time in the evolution of the animated film. Films like Mickey’s Christmas Carol, The Black Cauldron, Basil of Baker Street (terribly renamed The Great Mouse Detective by studio management) and Oliver & Company were wonderful training grounds for this new generation of animators. We were all very excited just to be there at that time, working on professional, big budget animated films in the lineage of Disney animated features and, though, artistically, some of the films fall short of excellent, you must put them in perspective here.

At the time they were done, they were cutting edge, as were the early Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons. Of course now, to look back, we can see the flaws. We can see the crudeness of some of the work and we may even cringe a little. But, those were very exciting and happy times for me and for others on the staff during that time and I would not trade the memory of them for anything. Oliver & Company is a clever and entertaining film. It is clearly of an era as are the swing films of the forties or the television cartoons of the fifties and sixties, and yet, there is something timeless about Disney animation that transcends dating keeping them fresh for each new generation that discovers them. That is the beauty of animation. It remains ever young.

AV: Lets talk about your overall career. You were dubbed “King of Cute” at CalArts. How did that happen?

DP: At CalArts, I had a tendency to be attracted to cute, appealing characters and I was good at doing them. So, as a joke, my colleagues and classmates dubbed me The King of Cute and that title stuck though I did go on to do a broad range of character types throughout the course of my career.

AV: Your desire to become an animator came after seeing Alice in Wonderland. What do you love in that movie particularly?

DP: I think that Alice, when I saw it on color TV in the early 1960s, sparked my imagination. I remember being awestruck by the Mad Tea Party and the colorful Golden Afternoon sequences. I remember, at the age of seven, turning to my parents and saying to them, “That’s what I want to do.” I didn’t even know what “that” was but I knew I wanted to make animated films. As far as Alice goes, it is one of the truly great Disney animated masterpieces in my book. It is one of the films made between 1949 and 1961 that I feel are some of the most wonderful and sophisticated animated films ever made. Films like Cinderella, Alice, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty and One Hundred And One Dalmatians are, to me, the finest animated films ever made, on every level and, in my opinion, are still unsurpassed by any other animated film made after them. They are national treasures and I believe they will endure as long as children are allowed to be children and as long as the child in all adults is allowed to indulge itself in the joy of these wonderful stories in beautiful Technicolor.

AV: Can you tell me about your memories of your animation masters, T. Hee, Jack Hannah, Elmer Plummer and Kendall O’Connor?

DP: These great teachers were a great gift to those of us who moved through CalArts at that time. Not only were these men (and I include our design teacher Bill Moore in this mix as well) great artists in their own rights, they were also experienced Disney artists who had been integral parts of the making of many of the most wonderful classic animated features of the golden era of Disney animation. Through these instructors and through Eric Larson and the other surviving “Nine Old Men” at that time, were passed many of the great secrets and techniques of Disney animation that are still only known to a handful of lucky working artists who were blessed with this passing on of this wisdom.

We were taught not just the technical and the artistic aspects of being an animator, but also the soul of being an animator. We were taught not just to animate, but to create characters, living, breathing, believable characters, that audiences could relate to and embrace. We were taught not only to just make things move, but to make them think and act and emote. Sadly, in seeing much of today’s animation, I fear that much of this is being lost, leaving characters more stereotypical and flat. My hope is that, though my teaching and the teaching of my animation peers, we will be able to pass on the skills and disciplines that were passed on to me and the others of my generation lucky enough to have gotten the inspired training that we did.

AV: Your first assignment at Disney was on Mickey’s Christmas Carol‘s Ratty and Moley. How did you work on those characters created during the 40s? How did you return (with Ed Gombert) to the fine Disney animation of that period?

DP: Well, that was just a wonderful experience. First of all, I was just starting out in the business and, though I was an entry level rough inbetweener, assigned to a great unit of animators: Ed Gombert, Toby Shelton and Jay Jackson (I also worked with John Lasseter whose office was just across the hall from Jay’s and mine). Ed was very generous in allowing me to animate small scenes as well as assisting the others in the unit. I assisted Ed, Toby and Jay on the Ratty and Moley scenes and was thrilled to do so because I just loved that era of animation and I particularly loved the Wind and the Willows story with Ratty and Moley and Mr. Toad and MacBadger and Cyril. Fortunately, the studio kept all the old scenes from every movie in the archives, (or morgue as we used to call it) so there was much reference material available to us to aid us in duplicating the look and feel of those classic characters.

AV: How did you work with Mark Henn on Basil‘s Dr Dawson? What do you keep from that collaboration?

DP: Mark Henn is an extremely gifted and natural animator. He just came to it with relative ease and seemed to understand the ways of Disney animation out of the gate. He took a liking to my work and animation tests at the time and asked for me to be assigned to him as an “Animating Assistant” on Basil of Baker Street. Mark then gave me many great scenes of Dawson and Basil to animate and, through our collaboration on those that film, Mark taught me much of what it was to be a Disney animator. I remember he would always pull me back and pull me back and hammer into me the lessons of subtlety in animation (something that not everyone understood then or now). It was frustrating at times, but ultimately very rewarding as I started to get it. Mark is still working at Disney and is still a top animator in my book. I will always be thankful for Mark’s generous time and tutelage.

AV: How was it to “co-animate” Flounder for The Little Mermaid? Did you share the task? How did you conceive Flounder’s animation during a sequence like Part of your World and manage to make him interesting while the focus is on Ariel? What was the challenge of that sequence?

AV: How was it to “co-animate” Flounder for The Little Mermaid? Did you share the task? How did you conceive Flounder’s animation during a sequence like Part of your World and manage to make him interesting while the focus is on Ariel? What was the challenge of that sequence?

DP: Flounder was such a wonderful character and sidekick for Ariel as were Sebastian and Scuttle. Barry Temple and I were pretty much the main animators on Flounder but other animators worked on the character, too. Again, the system of Supervising or Directing animators was still not yet quite in place. Mark Henn and Glen Keane were generally assigned to Ariel and Ruben Aquino, David Cutler and Kathy Zielinski were focused on Ursula. I also designed and animated all of the little sea horse messenger throughout the film. That was fun, too. You see, at the time, the department was still small and somewhat unstructured. That is not to say unorganized, but there was a lot more freedom of expression then, a lot more interaction between departments, too. I was able to not only design and animate the seahorse, but actually make color suggestions for him as well. This would be unheard of in today’s ultra departmentalized production.

But getting back to Flounder, Barry and I shared an office and each worked independently on our Flounder scenes, using prepared models sheets to keep the character consistent, but bouncing ideas off each other. It was great fun and I have such a fondness and respect for Barry to this day. The Part of Your World sequence was a real thrill and a collaboration between Glen Keane and I. Sometimes he would start a scene and then I would take it from him and add the Flounder level. Other times I would start with the Flounder level (such as in the scene where Flounder swims on his back and Ariel grabs him and swims off in the opposite direction) and then Glen would finish off with the Ariels. The trick was to never upstage the other character. Ariel would remain somewhat still while the focus was on Flounder and vice versa, you see? It was a give and take, really, and I think it came out just wonderfully.

AV: With Bernard and Bianca, just like for Ratty and Mole, you revived classic characters (this time as an animator) from 1977 for the theatrical sequel The Rescuers Down Under (1990). How was it to animate them? Did you do some specific research, or try to “update” them in a way or another?

DP: No. We did not try to update the characters. As I said earlier about Ratty and Moley, we had a great deal of reference material in the way of animation drawings, model sheets and film to draw from. The appearance of the characters was the easy part, really. The most important thing, though, was to get the character and acting right. Without that, it would appear like some other characters were wearing a Bernard or Bianca or Ratty or Moley suit and that’s not good.

AV: Can you tell me about your animation of Mrs Potts and Chip in Beauty And The Beast? What did you want to bring to those characters? How did you work on their personality and their movements? What are your memories of that very special movie? Also, how was it to go back to that universe in animating the Human Again sequence some years later for the Special Edition release?

DP: It seems, over the years, that I am most known for my work on Beauty and the Beast. My characters, Mrs. Potts and Chip, appear to have captured the imagination of people all over the world and wherever I go, when people discover that I helped to bring those characters to life, I get broad smiles and happy accounts of how beloved that film and it’s characters are, even to this day. Working on Potts and Chip was a wonderful and memorable experience and I loved every minute of it. It was really my chance to run with these characters as a supervising animator and I was lucky enough to work with some really great people on that film. Folks like Phil Young, Dan Boulos, Stephen Zupkas and others helped make the work a labor of love.

I remember thinking, from day one on this film, that it was really special. I did some preliminary work on Potts and then went on a two week vacation in Hawaii. Yet, I remember, as much as I love Hawaii, that I could not wait to get back and start animating again on Mrs. Potts! I enjoyed the great collaboration with Angela Lansbury, a top notch performer and consummate professional. I enjoyed working with my friends Will Finn and Nik Ranieri who did Cogsworth and Lumiere, respectively, even if they did not relish working with each other (a story for another time)! I loved watching the film come together, getting better and better as it did. I enjoyed the press junkets and the notoriety the film gave us animators for a brief period of time and the lasting audience support for the picture since its release. I recall the pride I had when Beauty became the first, and to date the only animated film to be nominated for a Best Picture award by the Academy.

This was, indeed, a very special time for Disney Feature Animation. And, best of all, I had the unique opportunity to revisit the role when it was decided that we would go back and animate the once cut Human Again sequence in the Summer of 1998. I loved going back to the film and really enjoyed working with Nik Ranieri again on a number of scenes. So, even though I would argue the idea that this is my best work in animation, I know that it is, by far, the most beloved film work that I have ever been associated with and I will always cherish that.

AV: With Aladdin‘s Sultan, you returned to working with Mermaid‘s John Musker and Ron Clements. Can you tell me about your relationship with those great creators and how you worked with them?

AV: With Aladdin‘s Sultan, you returned to working with Mermaid‘s John Musker and Ron Clements. Can you tell me about your relationship with those great creators and how you worked with them?

DP: Ron and John are both gifted animators and storytellers. The films that I worked with them on (Basil of Baker Street, The Little Mermaid and Aladdin) are amongst my most favorite of my career. I have always considered Ron and John not just colleagues but personal friends as well and I have tried to keep in touch with them throughout the years even when we were not working together. I think we share a mutual respect for one another and I am saddened that I was not able to come on board as part of their animation team on their latest film The Princess and The Frog.

Unfortunately, forces in management at the studio prevented that from happening this time around by making me an unacceptable and disrespectful offer that I had no choice but to refuse. That, I’m afraid, is the “New” Disney. They seem to have forgotten just who the people are who kept them on the map all these years and that is just sad for them. As for me, I just look to the future and other, more respectful and rewarding opportunities. As for the Sultan. What a great time I had working on that character. Everything just worked. The voice, the look, the humor and the warmth. I was so happy with the way that character came out and I still have many people tell me how much they love him. That shows me that the character was a success and makes me very happy.

AV: On Pocahontas you uniquely animated Flit totally from beginning to end. How was that?

AV: On Pocahontas you uniquely animated Flit totally from beginning to end. How was that?

DP: Well, I don’t know that I actually worked in order from the beginning of the film until the end. I think that what I meant by “throughout” was that I pretty much animated every scene that Flit was in, large or small. I remember one executive that shall remain nameless (mainly because the utterance of his name is believed to conjure up pure evil, ha!), after seeing dailies on a scene of mine in which they decided to blow up the Flit character making it a close up, told me that he was amazed that I would go to the trouble of putting all the expression and acting into a scene, even when the character was tiny on the screen, so that they could blow it up like that and it would work. I responded by saying, “Well, of course I would give it everything I had no matter what the size. This is Disney and there is no other way to do it.”

Flit was a great challenge in that he had no voice to fall back on, he was small so I had to work to make him read clearly to audiences, and I had to develop a natural approach to making his blurring wings work. Thank God I worked for the Disney of that time, a studio still dedicated to quality and therefore I got all the support I needed to make the character successful. I also enjoyed collaborating with Nik Ranieri and Chris Buck who animated Meeko and Percy, respectively. The three of us were really dedicated to making those characters work within the confines of the story to help bring humor to the mix. I am very proud of the work we did on Pocahontas and on the overall beautiful look of that film.

AV: With The Hunchback Of Notre Dame‘s Victor and Hugo, you got to work again with the Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale duo you met on Cranium Command. How did you come to animate these two characters like them, whom you seem very much attached to? Can you tell me about your personal relationship to the Gargoyles?

DP: Yes. It was another opportunity to work with long time friends Kirk Wise, Gary Trousdale and Don Hahn, all of whom I had worked with before at one time or another (Cranium Command, Beauty, etc), so I was a little disappointed that I might miss working with them again. You see, The Hunchback of Notre Dame was already well into production, as it was being developed while I was working on Pocahontas. In fact, I was slated to go onto Hercules, with Ron and John, and I was quite happy about that until Don Hahn approached me and asked if I might take on the characters of the two male gargoyles, at that time known as Chaney and Laughton, named after the two actors who had played Quasimodo in earlier film adaptations of the famous Victor Hugo novel. It was later that the character’s names were changed to Victor and Hugo, get it?

At any rate, the lure of these two inspired characters (good friend Will Finn collaborated with me and did the Laverne gargoyle with his own unit while I did the other two) pulled me away from Hercules and I hit the ground running on The Hunchback of Notre Dame, having only a scant eight months to do a hell of a lot of animation of these two prominent characters. And in that eight months, though exhausted, I had a ball. These were two unique characters that I could really sink my teeth into. More like broad 1940s style characters than classic Disney, they lent themselves to all kinds of outrageous humor and expression. Personally, I think these characters are the ones with which I was able to do the best animation of my career. In fact, I remember for the first time being able to watch my animation and see characters and not just drawings and mistakes. That was the biggest thrill of my career and that is why I am so attached to those two characters, carved in stone.

AV: Can you tell me about the character of Snowball in Kingdom of the Sun, the early version of what eventually became The Emperor’s New Groove? What were her story and personality like?

DP: Snowball was known to me as the “Prima Donna Llama”. She was a silly, vain and egotistical character, rather the dumb blond of the llama set. I really enjoyed developing the character and doing some early test animation on her as well. Before I left the film (and it was ultimately shelved), I created model sheets for not only Snowball, but for the rest of the herd of seven other llamas and for Kuzco as a Llama. The designs were more traditional and “cartoony” than what they ultimately went with when the film was revamped as The Emperor’s New Groove but, in my opinion, the influence I left is still there in subtle ways. It would have been interesting to see how Snowball might have been received by audiences, initial response to the tests I did was excellent, but that, I guess, is just something lost to the ages. For a better idea of what this film was like, try to get a hold of a copy of The Sweatbox, a documentary of the making of the Kingdom which was made by Sting’s wife at the time of production. It is a fascinating look into the way Disney films were developed at that time and, sadly, how this one rather fell apart.

AV: As the King of Cute, how did you manage to animate Harcourt and Packard following the designs of Mike Mignola?

AV: As the King of Cute, how did you manage to animate Harcourt and Packard following the designs of Mike Mignola?

DP: It, like all films, presented challenges. The Mike Mignola style was rather in contrast to my own style and the general style of Disney, but I was not without merit. What I generally did to adapt to the style was to begin drawing and designing in my usual way and then go back in and begin introducing the angles and planes required to push the characters in the Mignola style without loosing the appeal and solidity of the Disney look. Also, even though I did have a penchant for cute and warm characters, this did not necessarily limit me to those types. I feel that Flit, Victor and Hugo and other characters I have worked on have all worked together to help make me a versatile and well-rounded animator. In fact, a good variety of characters and designs and art direction help keep a good animator on their toes. Challenge is a good thing for animators. It helps keep them from becoming lazy or formulaic in their work.

AV: Can you tell me about your recent collaborations with Eric Goldberg for EPCOT’s Mexican Pavilion and with James Baxter on Enchanted?

DP: Both experiences were excellent. First of all, I so respect the work of those great animation artists, and secondly, I feel as though they respect mine. In addition to that, I also think of these men as my good friends and so it is always a joy when we get to interact and work together as like minded artists. I am just sorry that there are not more opportunities to work with them or another good friend, Ken Duncan. But, we keep trying.

AV: What do you think about the combination of 2D and 3D in animation?

DP: Well, when I was working in animation and CGI was coming in, the use of the computer was mainly to augment the traditional work. It was used to process the artwork though ink and paint, multiplane, the solid animation of inanimate objects or props, etc. To me, the computer was and is an exceptional tool that, in the hands of an artist, can be used, with great success, to bring production value and dynamism into tradition venues.

AV: How do you feel about the coming back of hand-drawn animation (especially at Disney?)

DP: It should never have left Disney. The move to destroy the department was both short-sighted and stupid and was brought about by ignorant and mean-spirited management that, for the most part, have been, shall we say, moved on to where they can do no more damage. I applaud the studio’s move to bring back the art form that made them once great. I just love the art form and want to see it flourish again, whether I am to work at Disney or not. The thing is, there is a place for all forms of animation in the marketplace today, traditional, CGI, Flash, stop-motion. They should not be in competition but in collaboration. Audiences love traditional animation. Students love traditional animation. Everyone seems to love traditional animation (save for a few embittered and confused managers who now do their dirty work elsewhere). It is time for the art form to return to Disney and I wish nothing but the most dramatic success and, “A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow”.

AV: Would you like to come back to Disney someday?

DP: As I said, I would have loved to have gone back to Disney to ply my craft again on The Princess and the Frog, and, in fact, all my colleagues were pushing for me to finally return to the studio. But, unfortunately, the studio management seemed to have developed a certain strain of selective amnesia since I left the studio and appear to have mistaken me for someone with no history and legacy in feature animation at Disney and elsewhere. Instead, management seems to see me as someone coming in off the street, with no experience of history, and so they saw fit to only offer me a scale salary, far less than what comparable artists are currently making, which left me no alternative but to decline the not so generous offer. But, that’s the way things currently are at Disney Feature Animation and it has not soured me on my love for the Disney I once knew and the joy I experience when I am animating on my own projects or the projects of another more respectful employer.

AV: How do you see the evolution of animation from your arrival at Disney, with the re-discovering of classic animation in the 90s, to today?

DP: Well, all I can really say is that I was extremely lucky to be at the right place at the right time, even if it didn’t always look that way while I was living it. Many people told me, in the 1970s (my own grandfather being one of them), that I would probably starve if I continued to move towards a career in animation. People told me it was a dead art form; that its time had come and gone. Still, I was undaunted. I knew what I wanted to do and I didn’t really care if it looked like a good idea at the time or not. I stuck with it and worked through the difficult times of change and growth in the industry. I worked hard to hone my craft and apply the principles and skills I learned to the characters on which I was assigned. I flourished when the films began to become successful and enjoyed nearly a full decade of great times on great productions working alongside some of the best animators and artists of our generation.

I was trained by none other than the best of Walt Disney’s era of animators. I was cast on fun and memorable characters and was supported in doing the very best work I was capable of doing for many years. And for all the above reasons, I will be eternally grateful and proud. I also hope that, though teaching, I will now be able to return some of the joy and satisfaction given to me throughout my career by passing on the principles of traditional animation which were handed down to me by the original Disney animators. I would like to see that these principles will be adopted by a new generation of animators and applied to the production of future animated films. That’s what I’m shooting for anyway. Wish me well.

AV: Can you tell me about your present projects?

DP: Oh, I am always working on something. Unlike other work, an artist does not put down his pencil or turn off creativity when the time clock is punched out for the last time or the paychecks stop coming. There is always something to do and I’ll be there doing it until I can do it no more!

With all our appreciation to Dave Pruiksma