Fleischer Studios/Paramount Pictures (1941 – 1943), Warner Home Video (April 7 2009), 2 discs, 145 mins plus supplements, 1.33:1 original full frame ratio, Dolby Digital Mono, Not Rated (packaging notes that this collection is for the adult collector and is not suitable for children), Retail: $26.98

Storyboard:

Superman soars on the motion picture screen for the first time, battling mad scientists, heat rays, giant robots, terrorists, natural disasters, enemy spies and even resurrected mummies in these seventeen iconic and hugely influential action-packed animated short film adventures!

The Sweatbox Review:

It must have been the early 1980s. I had been blown away by Richard Donner’s 1978 blockbuster take on the Man Of Steel, Superman: The Movie, and its sequel Superman II, obviously oblivious to that film’s own production problems at the time. Superman wallpaper covered my bedroom and I was an avid reader of the comic books of the era. So imagine my joy when I chanced – at a local flea market – upon a VHS tape that promised around two hours of Superman cartoons, something that would combine my following of Kal-El’s adventures on Earth with my other huge passion: animation!

Even at this youngish age, I realized the tape I held in my hands wasn’t exactly legitimate, but the thrilling artwork – still the best I’ve ever seen to illustrate these cartoons and a sleeve I dearly wish I had never lost – guaranteed lots of action and full-color cartoons by the Fleischer Studios. Hey, there were the names I recognised on those excellent Popeye cartoons! Wow – this must be awesome, I thought. I begged my mother to allow me to buy the tape there and then, but remember that for whatever reason, I had to wait until the following week…a week that went as slow as it could and was fraught with the terrible thought that my prized VHS might not still be there. Back to the market we went, and I blew all my savings on this one, incredibly alluring item.

Boy, I wasn’t disappointed.

The Fleischer Superman cartoons are truly, even now, in a class of their own. There simply hadn’t been anything like them before, since of after. Before Superman, cartoon animation had been of the cutesy Disney variety, the slightly surreal Fleischer output of Betty Boop and Popeye, or the lunacy of Warner Brothers, who still weren’t as crazy as they would eventually become, and everyone else who was basically out to try and reproduce those studios’ work. Snow White, Pinocchio and the Fleischers’ own Gulliver’s Travels had proven animation didn’t just have to be funny all the time, and developed truly resonant experiences for audiences. But it was in radio that fantasy drama really excelled, the special effects and budgets of film at the time not nearly reaching what could be imagined in one’s own mind, and one of the biggest successes of the moment was the audio adventures of Joe Shuster and Jerry Seigel’s strange visitor from another planet.

Making his comic book debut in 1938, Superman was a genuine phenomenon: as with the eventual cartoons, there simply hadn’t been anything like it, and readers’ imaginations were captured almost instantly, the nicknamed Man Of Steel quickly becoming a household name when he somewhat automatically joined the ranks of the other popular comic characters and became a hit all over again on the airwaves. A natural next step was the movies, with Paramount the lucky recipients of the distribution license thanks to their Popeye success, but live-action would prove a tough nut to crack (and would be, until Donner’s film managed to draw the resources and budget needed to make the world believe a man can fly). With Paramount already in business with the Fleischers, they assigned their new hot property to the Studio, the famous story being that Max’s brother Dave knew how hard these cartoons would be to produce from the outset and suggested a budget so astronomical that Paramount would have to back away from trying to bring Superman to screens.

But to Dave’s dismay, and our eventual fortune, Paramount stumped up the reported $90,000 per cartoon – over three times the usual cost of a cartoon short – asked for and Fleischer Studios had little choice but to enter the superhero business. With only the comics to draw upon as inspiration, as well as the slowly emerging film noir aspects of live-action cinema, Superman found himself immersed in a wonderfully atmospheric and truly sprawling Metropolis. This was a criminal’s paradise, visited dozens of times before in Warners’ gangster films starring Cagney, Bogart and Robinson, whose murky underworld was lit only by the light of the night sky, and promised danger around every alleyway.

It’s ironic that Warner should end up the rightful custodians of these cartoons, after years of being lost in the public domain, since they’re the full-blown Technicolor equivalents to those classic tough guy pictures: indeed, if the recent rumors were true (and they’re sadly not) that none other than Orson Welles had once planned a live-action take on Batman, it’s hard to argue that the result might not have been so far off the look and tone of these films. Already we had seen big-budget sci-fi on screen, most notably in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Alexander Korda’s version of HG Wells’ Things To Come, but they had been massive gambles in their time, and even such as big a budget probably wouldn’t have brought Kal-El to the screen convincingly in the early 1940s. Animation really was the only way to go: this is hard-core, pure original comic book Superman, with deep but vibrant colors that show off that striking costume handsomely, and Art Deco designing that place the world firmly of its day but retain a timelessly classy rather than dated feel to them.

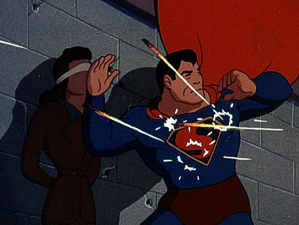

For the first time, a cartoon series would be relying on expressive, believable human characters, and as such they needed to be animated realistically. Some may take issue with the Rotoscoping employed in drawing the human characters, but I happen to think it’s among the best such animation ever produced using the process. The Studio’s Gulliver’s Travels had really improved the technique – actually invented by Max himself – and, if anything, had shown the artists how not to simply rely on tracing the live-action shot movements. The Rotoscoping in the Superman cartoons builds on this to pack in many tricks: the live reference of the Man Of Steel certainly doesn’t look to have been copied frame by frame, and there are instances where dropped frames insert a terrific illusion of speed or power, while the continued focus to get human anatomy correct results in some superior character animation. Likewise, their live-action actor could never fly, of course, and yet Superman pushing himself up into the air, and the feeling of weight as he moves through the sky is extremely impressive, beating Disney’s much touted similar feats in Peter Pan by a decade.

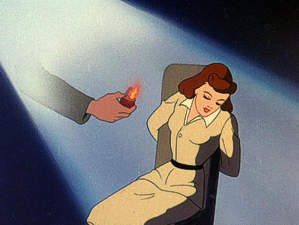

Sure, I’d agree with some that the cartoons can seem a little quaint, but this is an immense part of their charm and they’re none so more one dimensional than the whack ’em and thwack ’em television episodes today. They’re certainly on par with the original comic strips of the time: when Superman debuted he fought petty criminals and bank robbers, whereas this animated series faced him against stronger foes including giant robots, laser-like beams and natural disasters, and in Technicolor to boot (it’s easy to forget that, a handful of Popeye specials and the two features apart, Superman was the Studio’s only ongoing color series). In other respects, they’re incredibly faithful to Shuster and Seigel’s panels: Superman himself is the guy from the comics and while Lois Lane may not be quite as slinky, she’s still the smartest reporter on the Daily Planet, getting herself into various scrapes in an ongoing series of classically tailored outfits!

On the other side of the coin, this Superman series actually pushed the character forward in terms of development, instigating many of the personality traits and concepts that we associate with the Man Of Steel today. In the comics, Superman never flew: he famously “leapt tall buildings in a single bound”, but this was deemed to look ridiculous in animation and since he was basically flying once he took a jump, Action Comics allowed the Fleischers free roam to have him take flight. From the radio show, the popular cry of “Up in the sky, look! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!” was carried over, as was the voice cast: kids would have been dismayed if their hero hadn’t sounded the same on film as on radio and so Bud Collyer and Joan Alexander became Paramount employees in their roles of Clark Kent and Lois Lane respectively.

Brilliantly, Collyer brought with him the changing dynamics in Kent’s voice, the mild-mannered tenor becoming the booming baritone whenever “a job for…Superman!” looked like the guy in the big red cape was needed, and the Fleischers recognised that Kent and Superman were divergent characters: design sheets, with their own mannerisms, were drawn up for each as if to emphasise they were not simply alternate personalities of the same man. Apart from these facets, the characters aren’t exactly fully-rounded, but they’re still great fun: Clark is pretty much the bystander, waiting for intrepid reporter Lois to throw herself into danger chasing after another newspaper scoop, before Superman shows up to save the day. The formula stays faithful and true to this basic set up, but each cartoon always delivers upon the promise to be vastly entertaining and serves up just enough variables to remain interesting.

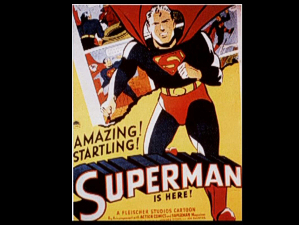

Superman, also known as The Mad Scientist, usually when featured in a compilation like this, was the pilot film that tried out the concept. Released on September 26 1941, it was an instant smash, with theater owners actually demanding posters and a trailer for publicity purposes. The Fleischers introduce the Man Of Steel to animation in a visceral and highly exciting cartoon that wound up being nominated for Best Animated Short of the year. It is positively a winner, even if it did lose out to Disney’s cute but routine Pluto cartoon Lend A Paw and had stuff competition from no less than nine other titles. It no less should have probably won, and it’s remarkably unbelievable that not one other short from this groundbreaking series was ever in competition again. Covering baby Kal-El’s lucky escape from Krypton, the cartoon swerves from the usual accepted history by having Clark grow up at an orphanage, presumably for reasons of time.

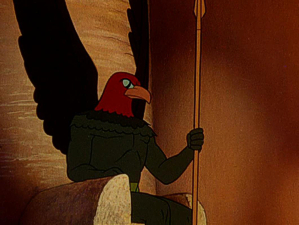

Superman is also already revealed to the world at this point, since Kent is already working at the Planet and no-one is surprised when the big blue boy scout shows up for duty when the mad scientist of the title unleashes his heat ray on the city. In a nod to the cartoon form, our villain has been given a very Fleischer-esque sidekick, a vulture who gets to have a little bit of business, though nowhere nearly enough to bring the cartoon down to a child’s level. This is all very superlative and exciting stuff, with Clark and Lois’ first words very cleverly coming from a radio, perhaps a nice nod to their previous incarnation, as Daily Planet editor Perry White calls them to conference. It seems a classically “mad” scientist has developed an electrothanasia ray able to destroy the city – and he intends to use it! The note that this disturbed individual sends to the press brilliantly alludes to his past, telling us literally in one image all we need to know. It’s enough for Lois, at any rate, who’s off in her plane to cover the story.

Naturally, Lois – and not for the last time – finds herself kidnapped and right in the wrong place at the wrong time, with Clark deciding that “this looks like a job…for Superman!” and making the first of his heroic changes in the Planet’s stock room. The cartoon is filled with such detail that it really warrants repeat viewings: this is fast cut, multi-layered filmmaking that’s impressive today, not least almost 70 years ago. As the ray hits the Planet building, watch as its lights go out, and marvel at the high levels of light and shadow at play – it’s clear Dave Fleischer, on getting his $90,000 from Paramount, made sure each and every cent was up on the screen. And what’s great about this Superman is that he’s not yet the invincible hero: although his strength is phenomenal, he often takes as much of a pounding as he gives before coming to Miss Lane’s rescue, for which she thanks him by hogging the limelight on the eventual Planet’s front page! “Great scoop, Lois!” exclaims Perry White, as Lois replies she “couldn’t have done it without Superman” and Clark gives us audience members a knowing nod and a wink, something else that would remain with the character even up to the recent final fly-bys in the movies.

From Sammy Timberg’s roaring main title march – an acknowledged influence on John Williams’ brilliant theme for the movies that uses a three note crescendo to literally sing “Su-per-man” for the first time musically – and filling in Superman’s backstory, to Lois finding herself in danger and the Man Of Steel’s battling against the beam, this first, triumphant cartoon packs it all in to an expertly told ten minutes, and it’s really these aspects that pull it over the frankly very poor presentation here. In fact, if I hadn’t seen the exact same print in the Ultimate Superman Collection and WB’s previous Academy Awards Animation Collection I’d have been writing for a recall, but assumedly this is the best that can achieved with the elements.

Not that it’s too bad, but the downside to Warners’ spectacular remastering is that this draws attention to all the bad points too: here the print debris is unrelentless, while a couple of splices in the audio (“truth and justice” becomes “truth justice” for example) make one wonder why they didn’t fix this with the same section from another cartoon’s intro. One other point on the audio is that it sounds amazingly ringy, such as in the days before MP3 when the only way to reduce a WAV file was to switch from stereo 44.1k to a mono 12k file, throwing out tons of info, the resulting frequencies sounding “digitised” and not very pleasing. All the high-end dynamics here sound this way, and it’s a terrible start to the set and not honestly the best I have ever seen or heard this cartoon looking. Unfortunately, it’s this version of the main march that also plays on the discs’ menu…ouch.

Such was the smash success of the pilot short that the series rolled into high gear, a new film emerging ever six weeks or so. Better in terms of presentation quality here is The Mechanical Monsters, from November 1941, and absolutely one of my all-time favorite short films. The film again opens with a short recap on Superman’s origins, though this is a one-minute or so cut down that doesn’t repeat the Krypton opening that would be spliced onto the front of each cartoon in 1950s television syndication. Immediately noticeable is the warmer sound, big, brassy and full of thumping bass, with Jackson Beck’s iconic opening narration booming through loud and clear. If your heart isn’t beating fast by then, the sight of the mechanical monsters themselves – huge hulking robots stealing fortunes from Metropolis’ banks – should get you going, and their stature in sci-fi shouldn’t be dimmed: these are the original such creations, still providing inspiration for such throwbacks as the enjoyably old-school adventure Sky Captain And The World Of Tomorrow.

Of course, with Lois and Clark covering the opening of the House Of Jewels, it’s not long before she finds herself inside one of the robots and on the way back to our villain’s lair…only for the guy with the big red S to come once more to her rescue. Again the use of shadow is immensely impressive as a tool in telling the story; it’s economically translated through the screen, again accompanied by Timberg’s fantastic music, brilliant as much as in the scenes it’s not used, suggesting that the soundtracks were as much a part of the storytelling as the action on screen. Here, Big Blue gets to show off his X-ray vision, and has a suspenseful entanglement in some power cables, while Dave and the animators show off a wonderfully lengthy and detailed travelling shot down underground where the villain plans to dip Lois in hot lava! There’s some serious action here, as Superman battles no less than twenty robotic beasts, taking a beating as Lois plummets to her certain doom! Yep, it’s all as overplayed as it sounds, and exciting as heck!

Due to the years of different handling by different distributors, an unfortunate result has been the removal of the Paramount logos on the front and tail ends of these films. Warners has managed to restore these, but only in so far as borrowing one set from a surviving cartoon and replicating these on the rest of the series. As such, the endings especially can feel odd, and that more wasn’t done to try and at least segue the music into one another feels like a bit of a shortcut: on more than one occasion, the splice is evident and the change jarring. Even stranger is that I have another collection of these cartoons with both the Paramount logos intact and with the original music playouts, so why better sources couldn’t be located is a mystery. One of the best looking in the set is Billion Dollar Limited from the January of 1942, in which some great train robbers attempt a gold heist but don’t count on Superman’s intervention. The designs rule this one again, from the bad guys themselves and their “bullet car”, to some excitingly atmospheric train animation and the daring heist itself. Naturally drawn to the gunfire, Lois finds herself in danger again, and the very geekish among you may pick out the four-note “danger” theme that Williams would later assign Lois in the film series (she also shows she can be as mean as the rest of them, handling a machine gun with flair!), while the Man Of Steel himself shows off some truly super feats of super strength.

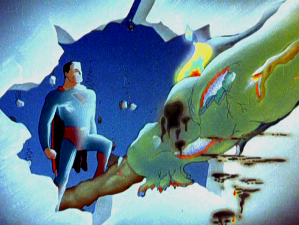

As we shall see, the Fleischers would not be able to stick with Superman through his animated cartoon career, and though many would belittle the later films, it’s fair to say that Max and Dave could throw in a goofy opponent too: just a month later, Arctic Giant finds Superman battling a thawed out dinosaur! Such shenanigans may seem just as prehistoric to us today, and logic is of course thrown out the window as the Godzilla-like creature escapes and the guards’ guns do little to stop him, but there’s a fun comic book angle on this one that makes it no less as suspenseful, and even the thawing of the monster is played seriously. Superman gets one of his very best full-frame store room exits (and we even get a glimpse at the odd way he would have jumped around in animation if Action Comics hadn’t permitted the Fleischers to simply have him fly), in a great actioner that has Kal-El saving a village from a broken dam by plugging the gap with giant rocks (so that’s where Chris Reeve got the idea!), and sharing some typical dialogue interplay with Lois.

Thanks to their New York roots, the Fleischer Studio was always more than adept at depicting the big city, with all its skyscrapers, in animation, and one only has to look at some of the Popeye cartoons and their later feature Mr Bug Goes To Town for some brilliantly realised perspective shots, and The Bulleteers has some of the best of them. There are also some very expensive looking crowd scenes in this tale of an organised crime gang whose flying bullet car terrorises Metropolis in a series of raids. It’s all a bit silly, but the details are there: Superman pulling Lois’ car from the rubble, being flung off the bullet car and resetting himself before leaping back into action; in the hands of a lesser team, these motions would have come off as stiff but they’re thrilling here, and the various angles as Superman finally grabs hold of the car and brings it down are sometimes genuinely astonishing for the time. Print quality here is fair, with the sound a little more muted than the other cartoons so far, but still much better than the debuting cartoon.

Another of my favorites – because I love dastardly scientists I guess! – is The Magnetic Telescope, the story of a confused genius whose wishes to harness the power of a comet puts all of Metropolis in peril! It’s the scale here that really makes an impact, from the professor’s observatory to the comet’s approach, though fun touches are Clark taking a taxi to the scene and changing in the back seat, to an interestingly green colored comet. Kryptonite, at this point, hadn’t yet been determined as a serious threat to Superman, but one could easily argue that its roots as a device for rendering Kal-El powerless could be found in these cartoons: after being knocked back to Earth once, he certainly doesn’t try to approach it again, choosing to rely on science instead to send it hurling back into space. Not only one of the best looking, edited and soundtracked cartoons in the series (the comet’s power helped immensely by the thundering sound effect), this is also one of the better conditioned prints, though the opening seems to have had a bit of chopping done to it in restoring the sequence, going by the cuts in the musical score.

Electric Earthquake finds another warped criminal getting his kicks by playing with nature, this time a disgruntled Native American Indian power charging his Earth shattering scientific equipment from his underwater lair. This is one of the few times Manhattan is confirmed as the inspiration for Metropolis, but there’s hardly any time to nit-pick: spectacular scenes of destruction and the Fleischer artists superbly handling the need for showing Superman “flying” underwater mark this one out for attention. These underwater scenes are great, showing more of the weight that the animators were able to bring to the character’s otherwise weightlessness, and more realism can be found in Superman not automatically being able to breath underwater: he can hold his breath as long as he likes, but he needs air as much as anyone, another nice nod to the fact that he’s not as invulnerable as he later became and must put up a bit of a fight to save the day. Although this does serve the suspense needs of the story, of course, these elements also give a little more dimension to the character in these stories.

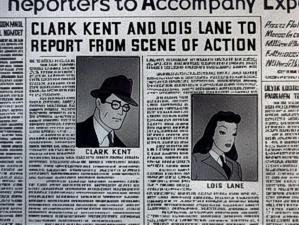

A disaster of a different kind strikes in Volcano, another of the more fairly straightforward cartoons in the series, but still with its touches: an early newspaper headline featuring images of Clark and Lois cleverly dissolves into the real things, while there’s a more than adequate quota of thrills and spills. Although the sound is solid during this outing, it has to be said that this is one of the rougher prints: sharpness and color aren’t a problem, but there’s a constant series of marks and debris that’s almost as bad as what the volcano throws out. Terror On The Midway, from the August of 1942, closes the chapter on the Fleischer’s involvement in the series. Here a Dumbo like circus is destroyed by a Gigantic, obviously a cousin of King Kong’s, who naturally takes a shine to Lois. The sheer size of the ape is cleverly concealed by often having him breaking from the boundaries of the frame, almost unable to be contained by the “cameraman”, while several shots may or may not have been intentionally framed out of focus but even these add to the atmosphere.

It’s a little too obvious, not really plotted that well and – with the big thrill supposedly being Superman fighting off circus animals gone wild – not that terribly involving, but there is a terrifically high production value, again mostly evident in the light and shadow work (a great shot sees a silhouetted Kent highlighted as police cars flash by). The print here is rather spotty; generally decent in places but with flashes of heavy wear – thankfully it’s not a greater cartoon or it might have been quite disappointing. That it was the last cartoon in the series produced by Max and directed by Dave might have been a shock if it weren’t for the fact that the Fleischer Studios had always had a rather tempestuous relationship with their distributor Paramount: like Pixar before Disney snapped it up, Max Fleischer was a free agent, making his own cartoons with Paramount’s money.

But previous run-ins with the bigger Studio over censorship issues with Fleischer’s Betty Boop had seen some cracks open up between the two entities, though while the Popeye series ran its course during the 1930s – and even outsold Mickey Mouse in merchandising – everyone seemed to have been happy, Paramount being so pleased with Max and Dave Fleischer’s work that they believed they could take on Disney in the feature animation game. Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs’ phenomenal 1937 success launched a series of similar fare, The Wizard Of Oz included, though closest in style would be Gulliver’s Travels, the Fleischers’ animated feature that arrived in theaters in 1939. The film was a sizable hit but heavily criticised for borrowing elements wholesale from Disney’s film.

The Fleischers, already in debt to Paramount, who had financed the moving of their outfit from New York to a luxurious facility in Miami, were ordered into making another feature, but from the start there were arguments over its tone and subject. The resulting film, Mr Bug Goes To Town (a title forced upon them due to the success of Capra’s Mr Deets, and later known under its syndicated television title Hoppity Goes To Town), is an excellent affair: the Studio at the top of its game. An original and contemporary story – arguably the first in animation – the film had the misfortune to open against Disney’s Dumbo, and just as Pearl Harbor was attacked. Mr Bug bombed, Paramount using the failure to order re-payment on their loan to the Fleischers. It was a payment that couldn’t be made, effectively ousting Max and Dave and seizing control of the facility.

Renamed Famous Studios, the regime change meant a difference in quality and the kinds of cartoons that would be made. Out went the gorgeously sophisticated black and white Popeye shorts, to be replaced by lower grade color comedy versions, while the emphasis was on bringing newer comic book characters – most notably Casper The Friendly Ghost – to the screen. But Paramount couldn’t let the prestigious Superman series go and ordered the shorts continue their regular production cycle: the now parent Studio was protective of the series and also wanted to maintain the quality, perhaps in order to satisfy their deal with Action Comics, who might have taken their character elsewhere.

Swapping over to Disc Two, the first of these cartoons arrived less than one month later, and instantly reflected the fears of the times: Japoteurs marks the series’ debut into politically incorrect territory by today’s standards, with Superman taking on a gang of Japanese spies intent on destroying an American super-bomber plane. Quality really isn’t an issue here, with the soon to be Famous Studio artists easily matching what had come before: the spectacle and scale is in full effect and great touches include wonderful shots of Clark moving amongst a crowd, perfectly lit in a sea of darker, drabber coloring. The racial stereotyping may feel uncomfortable today, but the character animation is absolutely terrific, as is the Man Of Steel’s saving the plane and landing it in mid-town Metropolis!

The first in the series to carry the Famous Studios name, Showdown is arguably the first of the films not to carry the Fleischer touches. Even then it’s a highly enjoyable outing, inevitably playing the doppelganger card by having a supposed “bad” Superman using his powers as a criminal instead of for truth and justice. Of course, this is an impostor in a Superman outfit, and a bad one at that: gone is the belt, replaced with nothing but bigger red trunks, and for some reason this minimal redesign has spread to Superman himself too. The easy way to tell a Fleischer Superman from a Famous Studios cartoon is to see if he’s wearing the belt or not, which further supports my argument that Japoteurs was probably in production during the shift of power behind the scenes. Another change is the introduction of a rather annoying Daily Planet intern, a much more cartoony personality that may as well be Jimmy Olsen but isn’t, though this is otherwise one of my favorites of the Famous shorts, with a great turn by an Edward G Robinson styled suave mastermind, and Lois looks a dish in her “new evening gown”.

Eleventh Hour spends a fair portion of its opening repeating Kal-El’s origins from Krypton, but is otherwise a fairly simple anti-Japanese wartime propaganda film which has the Man Of Steel sabotaging various factories and warships in Yokohama. It’s a pretty one-note short whose one interest is a nice bit of blurring Clark and Superman’s identities when he addresses Lois in the next room while slipping on a robe to disguise his costume. Also, as a sign that Sammy Timberg’s theme had become synonymous with the character, we don’t even see Clark change into Superman in this one: the storytelling instead being told through the music. There isn’t much else to this one, but if seeing Superman blasting the heck out of things is your bag, there’s certainly a lot of that kind of action here.

The last of the 1942 cartoons, released on December 25 (though mislabelled here as being from 1943), is Destruction, Inc, possibly the finest of the Famous Superman cartoons. Apart from an early, overly comic scene with the intern character, here named Lewis as part of the joke, this goes back to basics, with Lois going undercover to report on a story and finding herself in the thick of danger, naturally, with help coming from a surprising source…until all is revealed. From 1943 proper comes the January release The Mummy Strikes, which I’ll admit to loving for its ominous tone and the sheer amount of production design that evidently went into its creation. It’s slightly talky until the inevitable happens and a museum’s mummified remains are reanimated, leading to some major destruction, but the planning of these scenes really goes to show how good the Famous cartoons could be too, and there’s some truly spooky stuff going on in this one, accompanied by Timberg’s thumping score. A fairly obvious music splice suggests this is another cartoon that doesn’t feature the original end card, which again have turned up intact on other editions.

Jungle Drums again includes the full re-cap on Kal-El’s escape from the doomed planet of Krypton, and it seems to have been lifted from the first cartoon; the “truth justice” splice evidently using the same source, though this version is much cleaner in picture and sound than the one used in the pilot’s opening. It’s a terrific short, with some great voice acting and animation that really shows the Famous cartoons weren’t so far off the Fleischer efforts. Timberg almost outdoes himself with the rhythmic score, as Lois is captured by Nazi agent-sponsored jungle natives, and although racial stereotyping again rears its head, there’s some frankly stunning animation in this one: Dan Gordon’s direction packs in all the noir-ish angles one could hope for, and the epic nature is quite breathtaking. The ending even has Hitler reacting to the news that Superman has helped our boys in another mission, though the abrupt audio cut on the end title comes crashing in as ever.

Although the Superman cartoons had been arriving at the rate of one every month or so, perhaps the series’ end was signalled by the fact that it wouldn’t be for another three months before Clark Kent’s alter ego would fly again on screen. Released in the late July of 1943, Underground World marks what seems to be a return for the Dr Wilson character from The Mummy Strikes, though here called Professor Henderson, and possibly an influence on the later Professor Quest in Hanna-Barbera’s Jonny Quest program. One of the striking facets of the Superman cartoons, under Fleischer or otherwise, are the really quite contemporary sound designs, and quite often much of the impact of the storytelling comes from such simple things as just the right spot effects in the right place. But this is an otherwise simple and silly entry, with Superman saving Lois and the Prof from a flock of underground dwelling bird-men and their plan to turn them to stone, and it marks the first time that the series has started to wander off from its comic book plausibility and into the realm of fantastic unrealism, the opportunity for a mid-flight battle with Superman’s flying foes sadly missed.

Arriving on screens just one month later, Secret Agent again pits Clark against German spies, and even though there’s a very exciting car chase early on in which he is captured, it’s a pretty routine entry. The animation is still on the highest levels, of course, but the story – a blonde femme fatale who has been undercover must be protected in order to deliver some top secret enemy names to Washington – doesn’t do what it could with the potential. The unnamed blonde – otherwise a dead ringer for Lois – carries most of the cartoon herself until Clark escapes and dons the red cape, but I can’t have been the only one who was expecting her to whip off a wig and reveal intrepid investigative reporter Lois Lane underneath? That she doesn’t do this at the film’s end feels very flat, with Superman simply delivering her to her destination and flying off. The rather po-faced tone (both Clark and Supes are pretty dour fellows here) stretches to the violence, with a gunfight in which good guys and bad guys are pretty much killed on camera, seeming particularly gratuitous even in this hard-edged world. However Superman’s final shot is a red, white and blue flag fly by, and you can’t get much more patriotic, or closer to the character’s spirit, than that, bringing the total series of 17 animated shorts to a rousing close.

A popular comment is that the Famous Studios cartoons aren’t as good, or even as “legitimate” as the Dave Fleischer directed ones: I feel this is a ridiculous accusation. For one, with two features, a slew of Popeye cartoons and an ongoing Superman series to contend with, Dave couldn’t possibly have directed everything that had his name on it, and the fact that many of the following cartoons carry Isidore Sparber and Seymour Kneitel’s names on them suggest they weren’t just the lead storymen as credited on the earlier shorts. The same crews worked on these films, and they retain the Fleischer introductions, some even with new inserts, and there is a noticeable recycling of animation from the previous entries in the series. If the Superman series changed, it was in the producing Studio’s banner name only.

That the series continued without any incidents or hiccups in the production transition also suggests that the change was transparent, and that many of the same subjects would have been dealt with. Fans seem to forget that some of the Fleischer cartoons featured just as goofy plots or villains as the later Famous titles, and also that there are some truly great Superman shorts in this final set. Who’s to say that, had Max and Dave been allowed to stay, that the Man Of Steel wouldn’t have ended up battling Nazi spies anyway? That was the sign of the times, and might even have been one of the unspoken reasons the series came to a natural end: the comic books also had trouble dealing with Superman during wartime as a superhuman being who could have brought the whole thing to a halt faster than a speeding bullet.

With the somewhat short-lived series over and the Fleischers long disbanded from one another, it wouldn’t be until the cliffhanger serials of the late 1940s and early 1950s before Superman returned to screens. Now a live-action Man Of Steel in the shape of Kirk Alyn, even here Big Blue (or rather big grey, since these were black and white chapters) needed help flying, with animation again saving the day in a terrific switch that, if you can forgive the method, provides a whole heap of entertainment: Warners’ Superman: The Complete Theatrical Serial Collection is well recommended as something of a companion piece to this set, with the second serial in that collection being the stand-out and highly indicative of the tone that would continue with George Reeves into the 1950s on television.

For years, with each new incarnation supplanting the last, these Superman cartoons remained lost and forgotten, only surfacing in cheapskate public domain collections that treated the original films without the respect they deserved. For a long while, those editions were the only way to see these films at all – if you were lucky – but they had an influence that can not be measured or denied: those that felt the 1990s Warner animated television series based on Batman and Superman were superior in their tone and design need only be pointed in this direction to see where the roots of those aspects could be found. And as much as the stories may have been more layered, and the characters more rounded, their animation could never come close to matching the full, gorgeously handcrafted and painted traditional look of the high budgets of these 1940s classics. There’s been nothing like them since and nothing likely to come along in the future: for sheer super-heroic class, the Fleischer Superman series is impossible to beat!

Is This Thing Loaded?

Many have been waiting for a distributor to come to the Fleischer Superman’s rescue for years, with Warner Bros. leaping into action a couple of years ago to remaster these prints as part of their all-inclusive Ultimate Superman Motion Pictures Collection, which assembled all of the Man Of Steel’s theatrical appearances, from these cartoons, through the somewhat kitschy George Reeves feature Superman And The Mole Men and the four major Christopher Reeve movies, to the downright evil and desperately awful recent film that I can’t even bring myself to name.

For those with that collection, there’s no need to purchase this new set: you already have everything you need, including the documentary featurette First Flight: The Fleischer Superman Series. This brief, at under ten minutes, retrospective, which originally appeared on the Superman II disc in the Ultimate Superman set, actually isn’t the best of documentaries: it’s a bunch of the usual and expected talking heads – historians Jerry Beck and Leslie Cabarga, Max’s son Richard Fleischer and current DC custodians Bruce Timm, Paul Dini and others – expressing how new, different and influential these short films were, but that’s it. There’s nothing really on their production, no rare footage to supplement their comments and, most disappointing at all, any real reference to the Fleischers being ousted from their Studio and the remainder of the series being completed under various Studio directors. This will give you a passing semblance of knowledge about the Superman cartoons, but is otherwise disappointingly short and light on facts.

Not much better is The Man, The Myth, Superman, which shouldn’t that be “The Superman”? Although this didn’t show up on the Ultimate discs, you’re really not missing anything; a discussion by various scholars and notable writers which contemplates the lure of mythically powerful super humans, from Aboriginal cave paintings to the comic book superheroes of today, and our attraction to them as popular story figures. Some nourishing conversation about the importance of myths in our culture isn’t exactly waffle, but none of these speakers tell us anything that intelligent audiences won’t already acknowledge about Nietzsche’s concepts on the “Übermensch”, and more interesting is the snippet of what looks like old MovieTone footage showing young kids dressed in vintage Superman T-shirts. For much of the repetitive 13:30 minutes, my mind was distracted by the use of a piece of music used in a very famous early Ridley Scott commercial and all I could picture was Superman attempting to deliver a loaf of bread up a very steep hill!

The rest of the extras are all promotional advertisements, the biggest of which actually gets an unwarranted main menu option. Without seeing the disc, I’m presuming that this “first look” at the upcoming Green Lantern video feature comes from the Wonder Woman release from earlier this year, as it doesn’t actually seem to be anything new, and certainly not as advanced as the completed trailer that just hit the web. Why isn’t that included here instead of a potted history of the character, which didn’t get me jumping up and down to see his movie. On the second disc, we get the year-old variant on the Wonder Woman Comic-Con footage promoting that release and a promo for the Batman Beyond spin-off The Zeta Project. I’d have basically liked the Green Lantern material dropped, which is going to feel dated in a month or two anyway, and replaced with a more in-depth survey on the making of these cartoons.

Warners have never been hot on stills galleries, but I’m sure there’s enough character design, storyboard and poster artwork out there to make up a small selection, and how about that supposed theatrical trailer for the series…doesn’t that exist somewhere and wouldn’t have that made for a truly rare inclusion? Likewise, from the WB vaults, many of their Looney Tunes cartoons spoofed this series and it might have been real fun to include a couple of the authentically vintage ones, or even the wartime Snafuperman that was included by other distributors on previous collections. If they really wanted to play the trump card, the BBC made a terrific Arena documentary on Seigel and Shuster that looked at the character’s creation and translation to radio, which I’m sure could have been licensed for inclusion. Ultimately, this is a fairly decent collection of the cartoons themselves, but there’s a lot more that could have been done in the supplements, and has been on other releases.

Case Study:

Where fans might be tempted to buy is in the packaging, which is sheer class and the usual top drawer approach from Warners. A striking front cover image portrays Kal-El mid flight with a delectable looking Lois in his arms, while on the back she shares a plane ride with Clark alongside some action-packed stills from the cartoons. The text gets us excited about the discs’ contents, though why the “Man Of Steel” is bolded up when other names are not is a mystery. The cover’s title naturally keeps to the 1941-42 dates that the Fleischers were involved in the series, even though it actually ran until 1943, and this could lead to confusion (rest assured that all the cartoons are here). We’re presented all this on a very nice card slipcase, which reveals a standard keepcase from the side that repeats the artwork underneath. There’s no insert, but the disc art is perfect.

Ink And Paint:

I have already outlined the print and sound quality for each of the cartoons throughout their description above, but it would be fair to say, I think, that we’re still really waiting for the definitive Fleischer Superman series on DVD. Previous releases have either oversaturated the colors, tried to perform smudgy video paintbox cleanups or attempted, in the otherwise excellent Image Entertainment edition from some years ago, to dissuade copying by inserting the release dates over the main titles of each cartoon. I’m a little perplexed that original end cards and music – available as seen on other editions – have not been utilised here, replaced instead by the same standard playout each time.

The elements used here have been better mastered to the original Technicolor, but herein also lies the major problem: as well as all the vibrancy of the color, WB’s proprietary system also highlights every nick, scratch and mark of debris on the prints, making some sections tough to sit through as a plague of film damage and noise crawls all over the images. That sounds like a very rough description, but just don’t go into these thinking they’re going to look absolutely pristine. In short, they don’t, but there’s no faulting WB’s sharpness and compression tactics: these are very good representations of what can only be done with the sadly deteriorated source materials.

Scratch Tracks:

As with the images, the soundtracks have varied over the years, from el-cheapo distributors attempting to claim copyright on their “restored” editions by mixing into (or rather simply adding on top of) the soundtrack new spot effects, placed in so loudly in balance to the original tracks as to reduce the sound to nothing more than an act of butchery. The sound here is returned to their authentic mono recordings, and a bit of clean up has removed pops and audio hiss, providing a quite pleasing base thump. Once again, however, I must point out that unfortunate first cartoon Superman / The Mad Scientist’s really quite awful quality: as one of my favorites, and indeed an Oscar-nominated debut, that this is by far the worse looking and tinny sounding in the collection is a real shame. The others fare better, thankfully after a disappointing start, but on the whole they’re variably good and not so good, unfortunately down to years of mishandling rather than down to WB’s efforts. English and French subtitles are also included.

Final Cut:

It’s a big shame the first and possibly best in the series is marred by such audio and video artifacts, but overall Warners must be applauded for at least providing an “official” version of these cartoons when all we have had before are public domain collections. Is this the definitive release? No, and I would encourage really hard-core fans to search out a couple of the alternatives for different aspects, but these are the closest we’re ever likely to see to the original brightness and vibrancy of the original Technicolor intentions. That WB’s ultra-sharp transfers also bring out the print debris that goes with that process can only be put down to being an unwanted side effect of having these cartoons looking and sounding as good as they can, though it’s just such a shame – and one of animation’s biggest travesties – that this historic, important and downright entertaining series has been so mistreated over the years. Fleischer Studios not only brought the Man Of Steel to animation, but in doing so were also the first to bring Superman to life on the motion picture screen, in a series of films that remain a benchmark in the character’s screen history and are still super-remarkable and inspiring today!

| ||

|