“Once upon a time there were two children brought up by the same woman. Azur, a blond blue-eyed son of a nobleman and Asmar, the dark skinned and dark-eyed child of the nurse. As they grow up the nurse tells them many enchanting stories but their favorite is about the Djinn fairy waiting to be released from captivity by a good and heroic prince.

“Once upon a time there were two children brought up by the same woman. Azur, a blond blue-eyed son of a nobleman and Asmar, the dark skinned and dark-eyed child of the nurse. As they grow up the nurse tells them many enchanting stories but their favorite is about the Djinn fairy waiting to be released from captivity by a good and heroic prince.

One dark day Azur’s father cruelly separates them, he sends Azur to the city for a private education and banishes the nurse and Asmar from his home. Some years later Azur returns and sets out to a land far away to find the nurse and Asmar. Finally reunited, it soon becomes clear that Azur and Asmar will compete against each other to be the first one to rescue the fairy.”

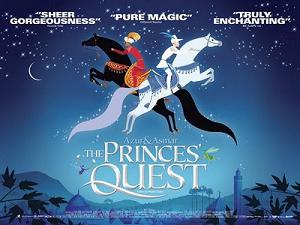

This is the new story animation wizard Michel Ocelot (Princes and Princesses) tells us in his latest masterpiece, Azur & Asmar: The Princes’ Quest. In this new visual amazement, Kirikou’s father is experimenting with a means of expression he hadn’t handled before, CG animation, and brings – as always with him – something totally fresh, definitely artistic and poetic to the medium.

Reconcilating the West and the Islamic world as well as 3D and 2D, he brings us a new and touching message about tolerance.

Animated Views: Azur & Asmar: The Princes’ Quest is a new tale about tolerance. How did you come to imagining/developing that story?

Michel Ocelot: I decided the interesting subject was: here and now. There are rich and poor countries, and poor people coming into rich countries, and the West and the Islamic world, and problems, some big, some small. If I bring some dignity and a sense of lightness to people, I am satisfied.

AV: Azur & Asmar is full of interesting characters, but I was particularly touched by the Little Princess. Can you tell me about her?

MO: In this story, I put together persons who are all different. I tried to gather several differences: rich/poor, male/female, Christians/Muslims, north/south and old/young. For old/young, besides an old person, I had to have a little child. I thought about the princess, with the idea of surprising people. They hear there is a pretty and intelligent princess, so they guess Azur is going to marry her. But, surprise, she is a little child. She is a child like Kirikou, with a fresh and clear mind and telling things as they are. This allowed me to help small girls as well, showing them they were not second-rate human beings.

AV: To you, why was CG the best tool to tell that story visually?

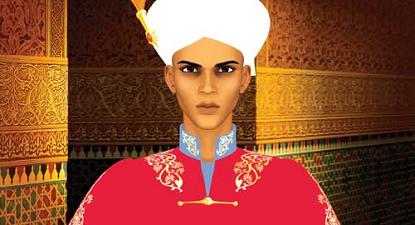

MO: CGI allowed me embroideries and jewels I simply could not afford in traditional animation; I enjoyed the possibility to play with beautiful sculptures (faces), having them moving slowly, possibly with complicated points of view, and still retaining their beauty; I was able as well to play with a big number of characters: the crowds in the city and the hoards of slave hunters; and I appreciated the possibility to check the animation at once, and do small improvements without redoing all.

AV: How did you come to appeal to McGuff Line for the production of the animation? What did you like in their work, and how did you work with them?

MO: When I thought it would be a good idea to do something with CGI 3D, I went to see most CGI companies in Paris. I watched the demo reels and I observed all the people around. My conclusion was that McGuff Line was doing a great job and that I would easily be friends with the people. The result is what I expected, we had a great time together and I liked the result.

AV: Your background is not in CG. How did you approach that new medium? What did you learn during that experience?

MO: It was my very first time with CGI 3D animation and I was wondering whether I would manage this kind of technique. I did, without any difficulty. CGI still IS animation. You have to be mad to have this occupation, and they were all mad. We understood each other well. Everything went smoothly. The 2D backgrounds allowed me more freedom, they are easier to do, playing with looks, collages and unorthodox perspective, and last but not least, they limited the complexity and allowed us to deliver on time without catastrophes. With this experience, I gained a better idea of what could be done and what could not be done with CGI. It means I want to make more films with CGI, and more films with drawings and more films with cutouts.

AV: Visually, the style seems to be based on a contrast between plain and pure shapes, and much detailed elements. Do you agree?

MO: This is correct. I played with: no shadow and no light on the clothes, a delicate shading on the faces and hands, set off by very intricate and rich backgrounds. It worked with no particular effort (just work, work, work). I avoided what I dislike in animation: photorealism.

AV: Where did you draw your inspiration for the arabo-andalousian elements (architecture, but also the jewels) and, for the 15th century, European elements?

MO: As the country on the other side of the sea was in North Africa, I went there to get first-hand information and to get the feeling of the place. And I surrounded myself with a lot of beautiful books on this civilization. The jewels of the maghreban women are traditional jewels from North Africa, which have been that way for centuries. For the oriental costumes of the two boys, I chose the fashion of Ispahan in the 16th century. Persian miniatures of that time are one of the summits of world art. For the clothes of the Europeans, I always had a lot of documentation (I chose the 15th century, which went very well with 16th century Iran).

AV: How did you build your color palette?

MO: I tend to always have a dominant color. It was green in Northern Europe for the childhood. It was dark and unpleasant for the landing of Azur, where everything goes wrong. Then it becomes more and more beautiful and colorful. The extreme being the market scene. Then I chose a golden dominant for the house of Jenane and all hues of blue for the palace of the fairy. I took away all colors for the palace of the princess, because it is actually a prison.

AV: How did you come to appeal to a live action film producer (Christophe Rossignon) to produce your animated film?

MO: I had a few successes which allowed me better budgets. I took advantage of it to try new things, not always playing the same trick as a circus pony. For Azur & Asmar, I experimented with a technique I had never worked with, I played with a language I do not understand, I offered myself the luxury of making everything in my own city and I went to work with a live action producer to look at things differently. Before choosing Christophe Rossignon (Nord-Ouest Films), I had seen several of his productions, they were all excellent. I had recommendations from people who had worked with him. I met him and I thought we would work well together. Again that was what happened and I want to continue working with him.

AV: The crew of Azur & Asmar is partly new (McGuff Line) and partly made of old (but not aged!) collaborators of yours (Christel Boyer, Thierry Million, Eric Serre, Anne Lise Lourdelet, etc). How do you work with your old collaborators?

MO: My answers are going to look too optimistic but the truth is, no problem arose. I prepared the film with my old (but not aged!) crew thoroughly and on paper. When we were ready, we went to the computer people and they were extremely pleased with what we brought to them. They thought that the film was better prepared than what they were used to. And we all had the same mission and we did work happily together.

AV: Despite the different medium, the style of the animation seems to be very close to the one of Kirikou (clear and plain gestures, economy of movements, elegance). How did you approach/direct the animation style of Azur & Asmar?

MO: I don’t really want to have a style, but it is clear that I like “immediate” beauty and elegance. In the case of Azur & Asmar, again I wanted a fairy tale look and not something looking like reality. And I was wary of CGI animation mannerism, nonstop moving of the camera, of the actors, complicated shots that did not interest me. I was not here to show what a computer can do, but to tell simply my simple story.

AV: How difficult was it to sell your film to the US market?

MO: I am simply trying to do the best work I can, period. I consider Americans to be human beings, not a market. Besides, I am not sharp enough to adapt to a “market”… Whenever I was able to show my films to Americans, they liked them. The only problem is having my films shown to the American public. No major distribution company wanted my film Kirikou and the Sorceress (unless I put bras and pants everywhere). Only a small one, half French, dared showing it here and there. Only one, again, was interested in Azur and Asmar. Unfortunately, this distributor kept the film in the box for two years, then declared that, as no cinema wanted to show it, they had to go straight to a DVD release. We protested, and the said distributor eventually found somebody (Eric Beckman, GKids) who did find cinema theaters that wanted my film. Azur & Asmar is now touring the United States and having fantastic reviews.

AV: Can you give us a peek at your upcoming projects?

MO: After the relatively heavy enterprise of Azur and Asmar, I felt like going back to something simple and short. I have many stories to tell and I start again telling ten of them in the shadow puppet theater I already used (Princes and Princesses and other shorts from Les Trésors Cachés de Michel Ocelot). This collection is for all ages as usual. But the following project will be for adults.

With special thanks to Michel Ocelot and Krystal Franklin at Bender/Helper Impact.