Walt Disney Productions (film: December 1963, television: February 1964), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (November 11 2008), 2 discs, 287 mins plus supplements, 1.66:1 anamorphic widescreen, Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround and Original Mono, Not MPAA Rated (some suggested aggression but nothing offensive, Canadian Home Video: G Rating), Retail: $32.99

Storyboard:

In the King George III-ruled, heavy taxation Britain of 1736, The Scarecrow fights for the oppressed people by disrupting the authorities’ plans and smuggling shipments of the over-taxed imports onto the mainland. When the King sends in new troops to bring order under the severe General Pugh, they find themselves faced with this formidable foe. This Treasure collects all three one-hour episodes of Walt Disney’s television adventure as well as the celebrated feature-film version in one package.

The Sweatbox Review:

It can never be stated enough just how good many of Disney’s live-action productions were. Vastly underrated and often lumped in with the admittedly sometimes cheesy vehicles of the 1970s, the earlier films followed the Disney template of tight storytelling, strong casting, solid direction and top-notch production values. Ever since the Disneyland television show debuted on October 27 1954, Walt had had the foresight to shoot his programs in color, even though only a fraction of the audience would see them this way, knowing that one day more suitable sets would be able to transmit and receive color signals and, when that time came, he would have a stock library of material ready to be shown again.

The early Disney TV shows were often plugs for the theme park, nothing less than hour-long commercials for new theatrical releases (only Walt could earn an Emmy for promoting 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea in prime time!) or repackagings of cartoon shorts. Alice In Wonderland became the first of the animated features to be sliced up in two for showing over consecutive weeks, but the first real specially made show was the first in Ward Kimball’s imaginative science programs, Man In Space. Disney was taking television as seriously as any other medium and understood that, while it could withstand a certain quota of library content, it primarily needed original programming and he put more money into these shows than he got back from the ABC network, Walt considering that he’d make back some more on merchandising.

Later in the first season of Disneyland, Walt got his first massive hit: Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter was the first of three episodes that launched a nationwide Crockett craze, powered by raccoon skin hats and a number one record, King Of The Wild Frontier that had been penned almost by accident when the first show ran short by several minutes. Not only would these episodes lay the foundation for many of the historical or legendary character-based shows to come, but Walt smelled a phenomenon and, acutely sensing that folks would probably pay to see it all over again in color, combined the three Davy Crockett shows into a feature-length release, where it became a hit all over again!

Over the next few years, Disney would repeat the trick, filming such stories as The Saga Of Andy Burnett, The Nine Lives Of Elfego Baca, Texas John Slaughter, The Swamp Fox, The Prince And The Pauper, The Horse Without A Head, The Legend Of Young Dick Turpin and another phenomenally successful series, Zorro – most of them shot for television and then sent into theaters – while many of the earlier live-action theatrical films became two parters on television: Treasure Island, The Sword In The Rose, Rob Roy, Johnny Tremain, Westward Ho The Wagons, Kidnapped, Greyfriars Bobby, Toby Tyler, The Three Lives Of Thomasina and Emil And The Detectives; films that shared the same kinds of production values and indeed became the first way many would encounter these productions.

Many of these were period pieces and westerns or were stories that reflected Walt’s interest in pioneers, mostly at the request of ABC who had positioned what had become titled Walt Disney Presents against NBC’s Wagon Train, though all of them had high levels of action, lots of intrigue and usually a catchy theme song that would fill airtime and provide music for a feature film’s opening credit sequence! Various arguments between the two companies would see ABC eventually dropping the Disney shows, including The Mickey Mouse Club and Zorro, from its listings and Walt would ironically wind up at NBC, where Walt Disney’s Wonderful World Of Color would help promote the network’s owner RCA’s color television sets by repeating earlier programs and producing brand new material.

By the time of Dr Syn, the practice of shooting properties for live-action feature film release and showing in weekly episodes on television was well established, and indeed many of these titles were actually shot with the feature film in mind first and the needs of the television adaptation second. Casting was always a strong point in Disney’s productions and here Walt went for a face that had become immensely popular in the UK: Patrick McGoohan. Making his debut as an uncredited “Guard” in a blink and you’ll miss him scene in the excellent account of the British raids on German’s Ruhr Valley The Dam Busters (1955), McGoohan rose to prominence in a series of tough guy roles, including the hard road drama Hell Drivers (1957), before landing John Drake, the original Secret Agent who beat James Bond to (television) screens by two years.

Dr Syn, Alias The Scarecrow (1963 feature film)

The Scarecrow Of Romney Marsh would give McGoohan international exposure and launch him as a movie actor, and he was pleased with a role that gave him many layers of subtlety between the character’s dual personality. The feature film version, Dr Syn, Alias The Scarecrow actually came to British screens in December 1963, a few months before the US debut on television as a three part adventure from the February of 1964. Although the feature is presented on the second disc, it’s probably advisable to begin here since of the two cuts this is arguably the one that’s made Dr Syn the cult favorite it is and differs in that one will probably find more to enjoy in the extended television version as opposed to then “missing” moments if watched in the order they are presented.

Disney had been making films in the UK since World War II, when Britain decreed that profits made from American films must be re-spent in the country to help it get back on its feet. Treasure Island, Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue, Kidnapped and many more features were shot and produced in England, where the locations naturally lent themselves to the kinds of old English folklore such as Robin Hood that Walt wished to bring to the screen. His television films followed suit, though Disney’s stroke of genius was to give such assignments to established feature film directors. At the time Dr Syn donned his terrifying Scarecrow mask, James Neilson had shot three pictures for the studio, including two that featured Walt’s leading faces: Fred MacMurray in Bon Voyage! and Hayley Mills in Summer Magic, in 1962 and 1963 respectively (he would go on to direct more films for Disney, including directing Mills again in her “coming of age” picture The Moon Spinners).

Neilsen’s staging, from Robert Westerby’s script based on William Buchanan’s adaptation of the Russell Thorndike novels, is serious, stirring stuff, and Disney’s production values clearly spared no expense: this is handsome stuff even for theaters, helped by the authentic locations (the film was shot in Dymchurch where the action was supposed to have happened, Walt paying for the restoration of Old Romney Church in return for its use in Syn’s parish). There’s also some very convincing day for night shooting too, well lit and treated, and more than passable for the dusk or dawn time that much of the action is set in, while the back-projected horseback riding is particularly impressive. The tone is well kept in check too: with an intense actor like McGoohan, Neilsen has no trouble keeping the balance of exciting activity and drama tightly paced, retaining not an ounce of what could easily become camp, but allowing a feel of flamboyant period filmmaking to run free.

The Scarecrow himself, based on an apparent real life Vicar who was supposed to have caused the King’s men some difficulty, is scarier than anything in Batman, and indeed as an early anti-hero vigilante type, there’s a good dose of Bruce Wayne in the Vicar/Scarecrow’s dual character. With those broad sticks on his shoulders, The Scarecrow cuts a stark figure in the dawn’s light sky, and the amazing make up job perfectly suits McGoohan’s wickedly maniacal laugh. Usually suspension of disbelief plays a part in characters not recognising the man behind the mask as the eyes often give it away, but as The Scarecrow you really can’t see it’s McGoohan. It’s an interesting role, too, because Syn never becomes The Scarecrow unless he needs to, often still carrying out his subversive work in his innocent guise as the local preacher, McGoohan playing both sides with an equal conviction and doing much of his bidding right under the oppressive soldiers’ noses.

It’s this walking, by McGoohan, of the fine line between his two roles so expertly, tipping towards the light and dark subtly as Dr Syn but treading into a firmly terrifying territory once he dons the infamous mask, that really carries both the film and television versions. It’s no exaggeration when the lyrics portray him as being from “the scarlet flames below”, riding from “the jaws of hell”…thrilling stuff! Known for being an intense performer, and wildly creative himself, there’s no doubt that the success of Dr Syn is down to the detailed portrayal that sees him almost give a nod and a wink to the audience, but never does, while delighting in scaring the opposition and us the audience, when the scratchy voice – which just is wood vocalised – and sack mask transforms him into something otherworldly. You just sense that McGoohan is taking it all seriously enough to still have fun with it, but handles his dual role with aplomb.

Of course the film would fall flat without sterling backup, and McGoohan has a choice cast of British stalwarts filling in all manner of roles. All the performances match the actually really gritty and semi-realistic tone being sought for, and which the film captures well. Despite the daring do, this is probably as close to a straight “horror” film as Disney ever got, and as serious for the studio, in its own way, until the much maligned The Watcher In The Woods nearly 20 years later. There’s no disguising the fact that people are shot, lives are threatened and they are all genuine, no empty threats. One man is even hanged – not explicitly on camera but still clearly intentioned enough in shadow. No wonder that when a rival version of the story from Hammer Films competed with Syn in theaters, it was to the Disney film’s credit that it was chosen and remains the most favored edition.

As Syn’s faithful right hand man Mr Mipps, George Cole proves what a great actor he is, forgoing the comic nature of Flash Harry in the original St Trinians movies, but tipping just a tinge of the sly into his performance, terrific support that never upstages McGoohan, and providing the light touch of gravitas he did as Bob Cratchit in the Alistair Sim version of A Christmas Carol. And you’ll see a host of recognisable faces, among them Michael Hordern as the troubled Thomas Banks, caught by circumstances between the orders of the king and his own appreciation for The Scarecrow’s work, Patrick Wymark as one of The Scarecrow’s men, Ransley, to turn traitor before pulling the same trick in Where Eagles Dare, Eric Flynn as the loyal but torn Lt Brackenbury, and Alan Dobie as the cold, calculating prosecutor Mr Frank, out to double cross whoever he needs to in order to capture The Scarecrow at any cost.

The eye of the stern General Pugh – Geoffrey Keen before popping up in a number of recurring James Bond government official roles – watches them all, under the orders of George III (Eric Pohlmann). Only Jill Curzon, the third point of a relationship triangle between Hordern and Flynn’s characters, hits a bum note, but thankfully Dr Syn is more interested in political intrigue than romanticism and she doesn’t get too much screen time in either version. In fact it’s just this sense of intrigue that motors along even the many dialogue scenes, full of McGoohan’s slyness and crackling dialogue, full of plotting and trickery. It’s the kind of swashbuckler where people listen at door cracks or from behind walls, pretend to be sleeping when the guards come checking and the villains get to say great juicy lines like “Fail me…and you are finished”!

The Scarecrow Of Romney Marsh (1964 episodes)

While Walt’s latest period actioner was playing in European screens, the full-length cut of Dr Syn’s adventures would come to television screens in the United States. Any accusations that The Scarecrow himself didn’t get enough to do in the feature film version are disregarded in this longer cut, which was actually syndicated in the 1980s, using the feature film’s credit sequence and shaving Walt Disney’s weekly introductions, to be shown as a two-hour, ten-minute epic, which I’m fairly certain is the edition I first saw. Certainly The Scarecrow’s riding off into the night with that maniacal laugh echoing in the sky at the end of the theme song reprise is one of the images that has stayed with me and one of the most genuine reasons I was eagerly awaiting the production’s debut on DVD to see again.

On television as part of The Wonderful World Of Color series, Walt introduces the story and characters before that song plays again: our first sighting of The Scarecrow uses the same footage as the theatrical film did for its title sequence, repeated at the top of each episode and reprised in part at the end, not only filling airtime in each program, but rousing viewers into the right frame of mood. A song was now standard Disney practice for any production – especially since the enormous success of The Ballad Of Davy Crockett – the hook being an important piece in drumming up marketing and an instant association with a character. Written by then-Studio staff composer Terry Gilkyson, it is here declared that The Scarecrow rides “from the jaws of Hell” (in the dialogue, Mipps goes as far as to suggest a comparison to “the Devil himself”), pretty strong stuff for the usually soft and cuddly Disney shows, and it certainly scared the heck out of me as a kid!

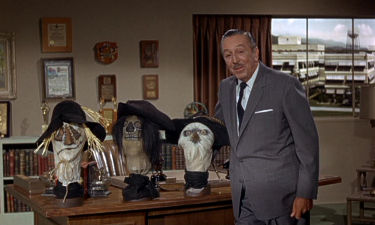

Walt himself is genial as ever, professing a great interest in the events of old England. His openings are more than just time-fillers, providing a little bit of history on the real Dr Syn and outlining where the action is about to take place, setting up the geography for American viewers who might otherwise not have an idea where the Kent and Sussex coasts and Dymchurch were…far way lands perhaps, but given a foundation under Walt’s twinkly eyes: as always, the old showman can’t resist dressing things up to boost the intrigue and levels of excitement. And, indeed, with the room to explore, the expanded version of the story isn’t just “longer”; it is, like any good extended cut, more in-depth and multi-layered, allowing for new characters to make an impact and for familiar ones to show extra shading.

Since the time of George III meant oppressive taxation for the people of Britain and also the American colonies, Disney introduces an American on the run, thus tying another strand into the plot that would resonate with native audiences. An escape to the colonies sub-plot by Hordern’s press ganged son, daughter and the now disillusioned Brackenbury is perhaps a further bid to interest US viewers, placing the story in the period that led to the War of Independence, the images of the king’s Recoats also recalling the similarly themed 1957 Disney film Johnny Tremain. This American character Simon Bates, a convict on the run for treason, does feature in both the television and film versions, but plays a slightly larger role here. The Scarecrow himself is more directly involved in the action, indeed he shows up in at least two additional scenes in full regalia, splitting the connection between Dr Syn and his alter ego fairly down the middle.

We also see more of the Vicar in his more natural church setting, where he continues to do The Scarecrow’s work by clever means of secretly worded sermons, abetted by Mr Mipps, who warns of the approaching press gang in a wonderfully smart fashion during one hymn. Characters and moments are expanded upon to reveal different attitudes: in the film version, Hordern’s Squire Banks seems to be (much as he hates their ways) very much on the side of the king’s soldiers, collaborating with Brackenbury to capture The Scarecrow or his men. With the chance for some added moments, we see that he’s not at all convinced of his own actions, emphasised by the fact that his own son was press ganged into the king’s navy. It’s one of many interesting subtleties that offers up extra characterisation and more subtext.

The first episode gains much of the additional material to the 98 minute feature, a total of 35 minutes or so throughout all three parts, though for re-cap purposes the arrival of Bates on the run is shown again in the third, which works but causes continuity confusion when watched in quick succession. Much of the last two thirds of the first program elaborate on the themes that, while are adequately served in the feature edition, are brought to the fore here: most notable is the actual arrival of the press gang, their stopover in a local tavern where Mr Mipps displays his cunning use of disguise to glean information and devise a set up, and we see just how uncouth the roughians were, a near the knuckle scene even for now, let alone family television of the 1960s! But despite the three-part nature, things never feel episodic, especially in the film version, which essentially loses the texture but keeps the core story so that it plays better in that form. Both editions work towards the same final goal, a tense and suspenseful climax in which a character’s allegiance switch is played, perhaps expectedly but without any falsity.

The Scarecrow Of Romney Marsh was among the last of the truly popular mini-series to air within the weekly Disney television program, and as audiences’ tastes changed in favor of movie of the week, crime, detective and sci-fi dramas, Walt found that the kinds of shows he pioneered were now being produced in-house by the networks instead of being bought in. When he died in 1966, the show continued through more name changes, but fell in ratings due to a decline in new programming, each week filled with re-runs or two-parter versions of the live-action theatrical films from the 50s and 60s. Dr Syn, Alias The Scarecrow bounced back to theaters, coming to the big screen in the US in 1975, which is where the cult success really began to spring up, the stark nature of The Scarecrow himself perhaps struck a chord with audiences of the time.

It may have also had something to do with the draw of Patrick McGoohan, too, who in the intervening years had become a big star and a familiar face on television. Already known for his role as Danger Man in the UK, shown as Secret Agent in the US, he followed Scarecrow up with the role of Andrew McDhui in The Three Lives Of Thomasina (1964), these two very different early Disney roles seeming to be an attempt to break away from being typecast. There is some documentation that confirms the further adventures of Christopher Syn had been destined for TV screens, but that it never happened could well be down to McGoohan’s Danger Man contract and the success he achieved in the unofficial follow up, the infamous The Prisoner (1967), which secured his reputation, leading to numerous appearances as a brilliantly formidable foil for Peter Falk’s Columbo and villainous feature parts including Ice Station Zebra, Silver Streak, Escape From Alcatraz, Scanners and Braveheart. He returned to Disney in the 1980s for the ill-fated Baby: Secret Of The Lost Legend and again in his most recent credit, to voice Billy Bones in the Studio’s Treasure Planet.

Although his creation of Number Six (or Number One, wink wink!) in The Prisoner will remain McGoohan’s legacy – a remake is currently being filmed for 2009 – it’s his terrifyingly iconic turn as Dr Christopher Syn, alias The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, that will forever be a close rival, especially in the eyes of Disney fans!

Is This Thing Loaded?

Dr Syn was rumored for release within the Treasures series as far back as the second wave, but has taken its jolly time in reaching the line up, for good reason as we shall see in the sound and image comments. But despite a number of additional extras that could have been included, it’s unfortunately a case of slim pickings here, and not all of them juicy.

The disc begins with the now ubiquitous Disney promo, but thankfully the Treasures remain free of any other company branding. Interestingly, the traditional Walt Disney Treasures menus appear in 16:9 for the first time, though frustratingly an Introduction with Leonard Maltin (2:43) reverts to letterboxed 4:3 format, a particularly curious decision. Maltin explains brilliantly the various ratios the production has appeared in, the high definition mastering carried out for this release’s transfer and the locating of the British sound masters that enabled a completely new mix to be created.

Also on Disc One, there’s a fine enough documentary featurette, Dr Syn: The History Of The Legend (16:15 ), which looks at both the real Christopher Syn, Walt’s fascination with the character, and the making of Disney’s version, also touching on the two other feature films to be made from the story. British Disney historian Brian Sibley, whom I’m always delighted to see turn up in such Disney supplements, leads the discussion, revealing how Russell Thorndike came up with The Scarecrow and how it was developed as a Disney production. Best of all, the reclusive Patrick McGoohan shows his pride in the project by sitting for a recent interview, which is all too briefly sampled here in spits and spurts, though the many behind the scenes stills and acute remarks make up a succinct featurette that covers all areas including Gilkyson’s song, even tracking down one of the original singers in the chorus.

Next, Walt Disney TV Introductions In Widescreen seems to have been included for no other reason than to add an extra bonus feature to the list. Though shot to the same wider format as the filmed production itself, these scenes are shown in the transfers of the episodes masked to replicate the 4:3 presentation as seen in television in 1964: here, as a separated group of three intros and two closing remarks that run four and a half minutes all together, they’re shown as originally shot, in full width. Quite why these versions were not inserted into the actual episodes is just baffling; they’re the exact same sequences simply shown without the sides cropped off. I love Walt, but I don’t need such scenes twice on the same disc!

The lack of thought appears to extend to Disc Two, which essentially houses the movie only, meaning that all the supplements should really have been stored here if just to even up the content spread. After another precise Introduction with Maltin – in which he manages to say more in his three minutes than anyone else does in the set – we’re unfortunately offered Walt Disney: From Burbank To London. There’s a terrific one-hour documentary to be had in Walt’s setting up a UK-based production outfit…but this is most certainly not it! A huge disappointment, this is just an eleven and a half minute gloss over a few facts, some of them actually wrong: Dr Syn, Alias The Scarecrow preceded the US television showing in 1963, not 1964, while McGoohan starred in The Three Lives Of Thomasina in 1964, after his role as Dr Syn, alias The Scarecrow, not that the production is otherwise evoked in this piece. As someone who has documented some UK Studios’ history, I’ve spoken enough to Disney’s contract star Richard Todd about his days on the sets of Robin Hood and Rob Roy, among others, to know quite a bit about this usually overlooked aspect of Walt’s live-action filmmaking career, and practically none of it is covered in the scant few minutes of talking heads and repeated photographs. It’s a fair enough overview, with welcome comments from director Ken Annakin and due dept paid to Perce Pearce and Peter Ellenshaw, but it feels very light and way too short, with a host of historians seemingly imparting well worded and flowery fluff rather than anything substantial, such as having someone like Todd’s reminiscences.

WHAT’S MISSING? I usually save a missing section for the Disney Platinums that strive to be definitive versions but seldom are, but the lightness and disappointing depth of the two supplements here compel me to ask why there isn’t more material included? With a three hour program on Disc One, it might have been more prudent to run both extras on the second disc, where there’s ample room – oddly, they saved the shortest extra for that disc too!? Dr Syn was one of the earliest shows to be broadcast in color, a decision that McGoohan would insist upon when producing his own The Prisoner: if the production of further new material for the disc was a budget issue then how about including the more than appropriate debut episode of The Wonderful World Of Color, from the September of 1961, that had new creation Ludwig Von Drake bring us through the history of Disney film, from the silent black and whites to sound, color and television?

If the wish was to keep to the serious nature of the program, then perhaps through the magic of seamless branching, we could have also been offered a third version: the 129 minute syndicated and home video edition that enthralled us in the 1980s? Or how about a short featurette detailing the differences in the cuts and the changing tones as a result? As a theatrical release, surely there’s an international trailer for the feature film version that could have been included, for the 1963 European release or the 1975 double-bill it played with Treasure Island? In fact, there is – I saw one years ago on video – so why isn’t it here? Likewise, there were a number of striking poster images created for both the television and, specifically, the feature showings of the film, some of them glimpsed at here, but a staple of the Treasures used to be the wonderful still frame galleries…here we don’t even get a token look at any of the production or publicity material. McGoohan is seen all too briefly in the documentaries, such as they are, and I’d have liked to have seen more of this footage too. The Scarecrow, for one, wouldn’t be too pleased!

Case Study:

Ever since losing the Roy Disney “autographed” signature strips around the fourth wave, the Disney Treasures have been pretty standard affairs, and collectors should know the drill by now: a deluxe tin case reminiscent of a film can, embossed with the Treasures logo and iconic image of the contents on the front, holds a standard double-width keepcase inside. A gummed on sticker on the back of the tin describes the treasures to be found within, but this is easily removed and possibly best tucked inside the case for safer keeping. The usual eight-page booklet outlines the Treasures and Dr Syn, covering the each discs’ content, while a Certificate of Authenticity reveals which numbered copy you have in a limited run of just 39,500 for this wave.

The disc art carries images for The Scarecrow on the first, and Dr Syn on the second, though the enclosed lithograph print is a bit boring: just an often used still of McGoohan; nice and atmospheric, but nowhere as exciting as a theatrical poster or even the montage shot used on the front of the box, though we do get that as the final page in the booklet. An extra insert lists the benefits of Blu-ray and offers the all-important Disney Movie rewards code, thankfully not promoted anywhere else on the packaging and ruining the consistency, something the Treasures, wraparound slip aside, have been great in keeping up.

Ink And Paint:

As mentioned above, The Scarecrow Of Romney Marsh had been destined for inclusion in the Treasures a good few waves ago but was mysteriously dropped. The reason now becomes clear: in sourcing original elements, the archive team discovered the British-shot 1.66:1 negative for the full cut, and decided to use this footage as the basis for a complete restoration. To use an often overused word, the results are, for once, truly spectacular, with the Technicolor bringing out General Pugh and the soldiers’ bright red coats with relish, and keeping the consistency in the day for night scenes persuasively believable, while the fairly muted and dark color scheme elsewhere still manages to feature a twilight world’s magical feel.

Most intriguingly, Walt’s office-based television introductions were also filmed to the same negative format, so for the first time we’re able to see these scenes in this way: that’s right folks, Walt Disney was shooting 16:9 material for television back in the 1960s! Unfortunately, the full width versions have been saved for the bonus section, while a masked 4:3 version has been used in the actual programs, which then open out for the actual Syn footage. Quite why the full width versions were not inserted is a mystery…as good as everything looks there are still minor frustrations which haunt the set.

Scratch Tracks:

Matching the picture is a newly mixed – from original elements – 5.1 surround soundtrack that, while not as luxurious as Sleeping Beauty’s simply overwhelming new mix, really does open up the film and certainly beats the also included original mono track for the film. Be aware that the mono track seems to play by default, though even this sounds pretty neat until the occasional music cue distorts ever so slightly, though not to its detriment and only due to limitation of the source. But the new 5.1 is very crisp, with the most benefit going to Gerard Schurmann’s rather John Williams-ian music, now lush and spaciously affective. Unobtrusively building on what was originally provided, the new Dr Syn looks and sounds incredible. English subtitles are included.

Final Cut:

This is a tough one to call. On one hand we’re looking at a fantastically entertaining and engrossing Disney production – provided in two versions that have been beautifully restored – but on the other this edition in the Treasures line is far from definitive, missing out a few very easy to include and natural supplements, and even dropping the ball on the ones that have been featured. I’ll have to go with the content of the main feature here and admit that I’m slightly biased as a Dr Syn fan. But this is perhaps the lightest and most unsatisfactory of the Treasures in the sparseness and accurateness of the supplements on offer…a major disappointment for what could have been a stand-out in the entire line. As such, I’m just glad to finally have both versions (but not the third!) on DVD looking and sounding so wonderful and, with those reservations, do recommend adding the set to your collections.

| ||

|