Madame Tutli-Putli boards the night train, weighed down with all her earthly possessions and the ghosts of her past.

Madame Tutli-Putli boards the night train, weighed down with all her earthly possessions and the ghosts of her past.

She travels alone, facing both the kindness and menace of strangers. As day descends into dark, she finds herself caught up in a desperate metaphysical adventure. Adrift between real and imagined worlds, Madame Tutli-Putli confronts her demons and is drawn into an undertow of mystery and suspense…

This is the basis for Montreal-based filmmakers Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski’s latest creation, produced by the National Film Board of Canada. In Madame Tutli-Putli, a 17-minute short film nominated for an Academy Award, the two award-winning directors, animators, sculptors, collage artists, screenplay writers and art directors take us on a mysterious, confusing, sometimes exhilarating and existential journey through groundbreaking stop-motion techniques where painstaking care and craftmanship in form and detail bring to life a fully imagined, tactile world unlike any you’ve ever seen.

Marciek Szczerbowski [above right] is our conductor, today. So, come aboard for the story behind one of the most unexpected and haunting journeys of all…

Animated Views: Who is Madame Tutli-Putli?

Marciek Szczerbowski: We wanted to make a kind of iconic figure, a kind of turn-of-the-century, classic lady. It’s a very particular kind of woman. It’s not every woman. Many women are far stronger than her. This is a delicate woman, a puppet-woman in a way, somebody very easily broken. We wanted to throw here into a world completely outside of her range of control, almost as though she stepped into another epoch and was hopelessly lost in it. And that epoch was in a way for us a kind of compression of the 20th century. The train is for us a kind of metaphor for the 20th century. It’s a question of a woman having to contact with that as though that experience were somehow the translation of the experience of her entire life. In a way, it’s a kind of rite of passage, an experience which takes her to the next level, let’s say, maybe a transcendental experience…

AV: Hence the transformation at the end.

MS: Exactly. But I hope you won’t ask me more about what it means because I want that to be your own interpretation. The reason for not wanting to explain that is that we care very much about building a sense of mystery and that’s something that’s lacking, I think, in art these days. People are afraid of mystery. People are afraid of being confused. Or rather, I think they’re afraid of trusting themselves. We asked people that we confused after seeing the film: “what did think it happened? What did you think it’s about?”, and they told us and they always were right. People have been conditioned to not trust themselves when they’re confronted with a mystery. They feel like they’re missing something, but they’re not. They’re just uncomfortable with not knowing. But we wanted to be very direct about that. We wanted to make that, if you build a mystery, you do not break it. The only thing you can do is disappoint people once you solve the mystery.

MS: Exactly. But I hope you won’t ask me more about what it means because I want that to be your own interpretation. The reason for not wanting to explain that is that we care very much about building a sense of mystery and that’s something that’s lacking, I think, in art these days. People are afraid of mystery. People are afraid of being confused. Or rather, I think they’re afraid of trusting themselves. We asked people that we confused after seeing the film: “what did think it happened? What did you think it’s about?”, and they told us and they always were right. People have been conditioned to not trust themselves when they’re confronted with a mystery. They feel like they’re missing something, but they’re not. They’re just uncomfortable with not knowing. But we wanted to be very direct about that. We wanted to make that, if you build a mystery, you do not break it. The only thing you can do is disappoint people once you solve the mystery.

AV: Not knowing about the solution make us share Madame Tutli-Putli’s anxiety, and that’s what make us see your film again and again and always appreciate it.

MS: Exactly. You know, I shouldn’t compare our film to a masterpiece like St. Exupery’s The Little Prince or something, because it’s not that. But I hope that it works in a way like The Little Prince works on me, which is that every time you go back into that story, you’re a little bit older and every time you read it, it’s about something else. First, when you read that story, it was a kid’s tale. When you read it as an adult, it is meaningful on a whole new level, and it’s actually about your adult life. And I think that, by not explaining everything to the audience as though they were stupid, you’re actually trusting their intelligence and you’re letting a piece of art age with them, stay with them. I think it’s very important.

AV: How did you find Madame Tutli-Putli’s name?

MS: It’s a reference to the work of Polish writer Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz [right]. It’s the title of a book he wrote in 1920. We found it by being very interested in the history of 20th-century art. So, there was once a Madame Tutli-Putli. She was rather a “Miss Tutli-Putli” and we kind of stole her from the world of art and we threw her into our time, so she’s a little older. But has several meanings. It’s a word in Hindu that has two meanings, which are both quite perfect for this. The first meaning is “a very delicate woman” and the second meaning is “a puppet”. It’s also phonetic. If you say the word, you like saying it. It gives a clue as to her character. She is that. We were hoping that the way she behaves and the way we react to her actually echoes her name, since her name is a piece of her color, her character.

MS: It’s a reference to the work of Polish writer Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz [right]. It’s the title of a book he wrote in 1920. We found it by being very interested in the history of 20th-century art. So, there was once a Madame Tutli-Putli. She was rather a “Miss Tutli-Putli” and we kind of stole her from the world of art and we threw her into our time, so she’s a little older. But has several meanings. It’s a word in Hindu that has two meanings, which are both quite perfect for this. The first meaning is “a very delicate woman” and the second meaning is “a puppet”. It’s also phonetic. If you say the word, you like saying it. It gives a clue as to her character. She is that. We were hoping that the way she behaves and the way we react to her actually echoes her name, since her name is a piece of her color, her character.

AV: What would you want the audiences to retain from your film? The unique storytelling or the technical improvements?

MS: What we expect as directors is that audiences have their own reaction to the film, free and honest. We tried to do something both cerebral and emotional. We just hope that the technical aspect to it will be quickly forgotten as they dive into the atmosphere of the film.

AV: There is no dialog in your film. Just storytelling through animation and music.

MS: You’re right. Music is terribly important. The soundtrack influences up to 80% the way the film can be felt and understood. So, we were very fortunate to get excellent musicians like David Bryant and Jean-Frédéric Messier in Montreal who created a great soundtrack that hopefully enhances or supports the emotions on screen, oscillating between traditional score and atmospheric sounds.

AV: How did you build up this story?

MS: Many people think that artists like us find the inspiration just by walking in a street. But, for us, it was more comparable to looking at birds in the sky. We see something, we catch up images, and we keep the most iconic and significant ones. So, when you’ve collected a bunch of strong images like that, an interesting dialog begins between each other. Images begin to talk to each other and you find a fragile balance between them. So, our aim was not to tell a tale, but to carefully take all these elements and, just as carefully, put them in another place. Because we consider that short film as a genre has to be something very unique, very independent. It’s not a rehearsal in view to making a feature-length film. It’s a form that has its own rules. And we thought that a short film like that had more to deal with poetry than with romance or anything like that. A poem has structures, but its structures are not always logical. A scene in a short has not to be the consequence of the former scene, yet a scene can inform the former. So, we wrote this film more like a poem.

MS: Many people think that artists like us find the inspiration just by walking in a street. But, for us, it was more comparable to looking at birds in the sky. We see something, we catch up images, and we keep the most iconic and significant ones. So, when you’ve collected a bunch of strong images like that, an interesting dialog begins between each other. Images begin to talk to each other and you find a fragile balance between them. So, our aim was not to tell a tale, but to carefully take all these elements and, just as carefully, put them in another place. Because we consider that short film as a genre has to be something very unique, very independent. It’s not a rehearsal in view to making a feature-length film. It’s a form that has its own rules. And we thought that a short film like that had more to deal with poetry than with romance or anything like that. A poem has structures, but its structures are not always logical. A scene in a short has not to be the consequence of the former scene, yet a scene can inform the former. So, we wrote this film more like a poem.

AV: Like a dream, also…

MS: Not in the sense of a fairytale dream, of course, but yes. We tried to do our editing like we would edit things within a dream… In the alphabet, you’ve got A then B then C, but in a dream, your brain can choose to connect A to C. That’s how we approached our editing, and there lies the poetry.

AV: Because of that, I imagine that the storyboarding process was very complicated.

MS: Not just complicated, but totally useless! We began doing storyboards, but very quickly, we realized that it didn’t work. It made something pedantic and static. Storyboard drawing is not at all our film’s language. It’s comics vocabulary whereas our film’s language is a cinematographic language. The camera is moved; it’s a moving experience, and that’s what makes it different from theater. Storyboard caught us in the world of theater, so we threw it into the lake and we invented another way. We did rehearsals with actors in our studio, we shot them and studied their gestures.

AV: How did you direct them?

MS: We gave them a little bit of liberty to improvise, of course, but we knew exactly what we wanted. We acted like a cameraman, by running around and filming things in a very live and spontaneous way. I think we managed to address cinematography in animation. We didn’t think of it as a cartoon but actually as a film which moves, which has dynamic. And that was very important for us to reproduce in the film the gestures, the kind of nuances of femininity and the way that the camera behaves. Hopefully, bringing the film into the world of cinema rather than the world of animated cartoon.

MS: We gave them a little bit of liberty to improvise, of course, but we knew exactly what we wanted. We acted like a cameraman, by running around and filming things in a very live and spontaneous way. I think we managed to address cinematography in animation. We didn’t think of it as a cartoon but actually as a film which moves, which has dynamic. And that was very important for us to reproduce in the film the gestures, the kind of nuances of femininity and the way that the camera behaves. Hopefully, bringing the film into the world of cinema rather than the world of animated cartoon.

AV: How did you come to choose stop-motion to tell this story?

MS: Stop-motion is one of the oldest and slowest way of doing films. But that allows to have the greatest control on your film since you can adjust each frame after the other. It’s a form of illusionism, a magic trick to give inanimate, dead objects the illusion of life. So, it’s simple, but always magical! It’s not that we think that it’s a superior medium to CG imagery or anything like that. We just feel that it has a very special charm. You’re capable of watching the most banal actions in stop motion, and feel something. The crazy thing about it is that it’s actually real. These puppets exist. It’s not a computer fabrication. It has real lighting and real shadows and that kind of makes a “half world”, a world half way between the three-dimensional world we live in and the fantastical world. It happens to link to both and that’s the huge power of the medium. It creates a nervous reaction instantly.

AV: How did you create your puppets?

MS: They’re quite standard actually. They’re made out of wire which we bought at a hardware store for $5, and the skin is made out of silicon which is a pretty common material in sculpting these days. I think that where we had the most fun was making the hair out of bird feathers, for example, or making costumes which we buried underground for three weeks and then unburied, to make them look degenerate. We’re very much about a tactile experience. We’re kind of object fetishists: we love touching things with our fingers. So, the sculpting and the building of the puppets is a very kind of rewarding process for us. We would not give that up to anybody, especially a computer designer because it’s actually a bit of a thrill for us to be touching objects with our fingers. And in a way, I hope you can sense that. I hope, when you’re looking at the film, that everything you see on screen, you realize, is made by our fingers and has a kind of continuity, its own cohesion.

AV: Can you tell me about the technique you developed for the puppet eyes effect, which is a first in the field of animation?

MS: We’ve done puppet animation for many years and we had a kind of dissatisfaction with the limited range of expression that glass doll eyes can give you, and we needed Madame Tutli-Putli to be a very contemplative character. We needed to see into her mind, you know. We needed to show her anxiety, her apprehension and the kind of mental process going on inside her head. So, we tried something very crazy which is to composite the eyes of a live human onto a puppet, after the animation. And it worked! And it created, I think, a kind of new way to relate to the performance. It actually seems like you’re watching a performance rather of a puppet, which is very important, but a super-difficult process of working with actress to very, very careful match all the angles and the lightings that happen on screen. We had a great friend whose name is Jason Walker, who is a Scottish painter. Not a computer guy, but an actual master oil painter. He did a wonderful job by blending the human eyes onto the puppet’s face.

AV: You told me that you drew your inspiration from iconic elements. Are there specific references in your film?

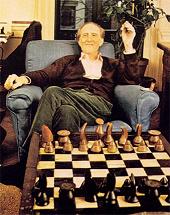

MS: We’re interested in the tradition of art and the influences are all over the place. There are influences from Polish writer Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, whose spirit we tried to kind of contain within this tale, a kind of spirit of independence. We were also much influenced by the movement of Dada. The monster thieves, for example, that enter the train, are based entirely on a costume that George Grosz, the German painter, had made one time for a Dada ball. The chess players who are having a game in the suitcases, up in the car there, are modeled on Man Ray, the photographer, and Marcel Duchamp [right], the abstract artist. As you know, they were friends and they enjoyed playing chess. So, we kind of channeled them into this film. The pervert is kind of loosely based on a Polish writer named Jerzy Kosiński, who wrote some very, very heavy work.

MS: We’re interested in the tradition of art and the influences are all over the place. There are influences from Polish writer Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, whose spirit we tried to kind of contain within this tale, a kind of spirit of independence. We were also much influenced by the movement of Dada. The monster thieves, for example, that enter the train, are based entirely on a costume that George Grosz, the German painter, had made one time for a Dada ball. The chess players who are having a game in the suitcases, up in the car there, are modeled on Man Ray, the photographer, and Marcel Duchamp [right], the abstract artist. As you know, they were friends and they enjoyed playing chess. So, we kind of channeled them into this film. The pervert is kind of loosely based on a Polish writer named Jerzy Kosiński, who wrote some very, very heavy work.

The train itself is based on a kind of European, half-way-through-the-century vision of the future, like, during the 60s, we used to think the future would look, and the kind of design that was being made for expos and technical fairs. They were inventing the future in a way and making things so futuristic-looking. Those are the flaws of our manifestos, and it’s never worked. Twenty years later, that train no longer looks futuristic. It looks broken. Those are things that we were gathering, that are iconic for us, that are loaded. You see a perfect train that has been built to look like a spaceship or something, a capsule, unbreakable and clean. In five years, there will be a fly that goes into the light fixture and never comes out and dies. And you’ll see a black dot inside of that lamp for ever. It will ruin that whole idea of the future design. Nature will somehow find a way to break down all our crazy manifestos. In a way, that’s what Tutli-Putli is. Tutli-Putli is that black inside the lamp fixture, the insect that got caught inside this sort of race for speed, for taking society further this philosophy. That’s something that can actually destroy a little, fragile, delicate creature.

AV: How is it to be in Hollywood, competing for the Oscars?

MS: Let me tell you that: this is not an artists’ world. We are in Los Angeles and this not where you do art. This is where you do business, where you do castings, where you make the deals for the distribution, but this is not where you do art. And you can feel that. This may be a very snobbish way to look at it but I think that good art comes from the periphery of the main stream.

AV: What do you expect from that?

MS: Are you kidding? I don’t expect anything! You know how utterly and completely satisfied we are with what has happened with this? One month after we finished it, we were accepted to the Premiere in Cannes. For us, it’s the top, really, and we won, and we came home thinking: “wonderful! That’s it! That’s all we could have ever, ever wanted!” And since then, it’s been nine months of festivals, awards and talking about ourselves. The thing that’s been the greatest pleasure is not winning prizes, but the fact like someone like you, living in a foreign country to us, has somehow become engaged and it somehow made a tiny, tiny difference in your life.

That’s all we could have hoped for by making a strange and challenging, obscure short piece of work. Actually, a nightmare. We threw a nightmare into the world thinking that, maybe someone will care. And people do. People who have reactions to art. It reminds us that art might still actually matter. We really don’t need anything else. We actually really want to get back to work!

“The Crazy Locomotive” refers to the title of a 1923 book by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz.

Our special appreciation goes to Maciek Szczerbowski and Winston F. Emano for this interview, and to Josh Armstrong for his great help.