In a more than fitting close to our exclusive Little Mermaid interview series, Jeremie Noyer continues his dive under the sea and back to Ariel’s beginning to meet with two very special people. Howard Ashman, the original 1989 film’s lyricist and legendary Broadway musical genius, is remembered here by those who loved him: Sarah Gillespie and William Lauch…

Who gave a mermaid her voice, and a beast his soul.

We will be forever grateful.

Howard Ashman

1950-1991

It’s in those terms that the Disney artists chose to dedicate their classic animated film Beauty and the Beast to the man who was instrumental in the revival of Disney animation during the late 1980s and early 90s. A one-of-kind artist, pervaded by magic, always eager to share it with extraordinary generosity and talent…and an irresistible touch of humor!

The release of The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning and the production of The Little Mermaid on Broadway give us the perfect occasion to go back to the origins of the myth and pay homage to one of the visionaries who gave life to Andersen’s mermaid in a unique way. So, in order to do that, we turned to the people who have certainly been the closest to him and have know him best, his sister, Sarah Gillespie [above right] and his friend and partner William Lauch [below right].

Both of them were kind enough to answer our questions, as we all share the same admiration for the authentic genius that Howard Ashman was.

Animated Views: Everyone who met Howard remembers him as somebody unique. To you, what made him so special?

Animated Views: Everyone who met Howard remembers him as somebody unique. To you, what made him so special?

William Lauch: I would say his passion. Be it in his professional like, at Broadway or in cinema, or in his personal life, with his friends or as far as the causes he defended, he did everything with passion. He was passionately interested in everything. No only musicals. He loved design, architecture, just like me – I’m an architect – and cooking. Yes, for me “passion” would be the word that characterizes Howard the best.

Sarah Gillespie: That’s hard, because I knew him since the day I was born. He had so many talents. One is, he was a very warm person. He had a very real desire to be a father to people. And that came out in the way that he directed, in the way he worked with actors as well as in his friendships. He was a director when he wasn’t directing. For me personally, he was very much a mentor. And he was usually right. As a talent, he began, when we were children, in children’s theater and he was an actor and a performer. He also began writing very young. There was always this need to express himself and to create. He had interest in comics as well. I truly think he was a visionary. As for Disney, he really did love animation. His first introduction to animation of course as everyone was a Disney film when we were children, and our grandmother took him. And it was one of the things that inspired him to go into theater. He wanted to be “part of that world”! When he got that opportunity from Disney, and Jeffrey Katzenberg basically said: “We have this project and this project. What do you want to do?” It was the idea of working in animation, and on fairytale that was so important to him and so exciting to him. When we were young, Howard created a fairy land for me. It was in his bedroom and he used little plastic figures of people and animals and decorated the room with cotton and fabric and whatever else he could find. I don’t remember exactly how he did it, but I was very young and it was magical. It was just something he did one day, for fun. He wrapped his head in a towel to make a turban (almost like a genie!) and led me into this magical land he had created. It gives me great joy to think that in adulthood, that is something he was able to do for so many…

AV: So, it’s animation that led to theater!

SG: As a child, yes. It was one of the elements. Our mother also was a singer, she was a semi-professional, so we always had music and musical theater in the house. But the first movie-musical he saw was a Disney animated movie musical. And there was a very strong connection there. I think the other thing that charmed him about animation was that you could do anything. So, he could really use himself creatively, he could go wild with his imagination…as he did in Little Shop, even if it’s not animated.

AV: As a matter of fact, Audrey II is a kind of an animated character.

AV: As a matter of fact, Audrey II is a kind of an animated character.

SG: Absolutely. Audrey II is a cartoon character. When you think about Audrey II, it’s a cartoon character that’s silly and funny and broad, all of the things that Little Shop is, not at all realistic, but has real wants and desires. And that always was very important to Howard. Your characters have to have wants and desires and they also have to by funny and broad as with Ursula. You can really have fun with those perverse and very strong and odd desires!

AV: Didn’t he build his very first theater in your garden?

SG: In our backyard, yes! As a little sister, I got to get cast and everything! We would charge money out to our parents and neighbors and he would set auditions and direct, and did the ads. We did scenes from Gypsy as children. He even set up in the basement of our house and made a scrim with a sheet for the strip tease that there is that musical. So, he got very elaborate. There was also a group called Children Theater Association that was run by a wonderful woman and that Howard became very much a darling of. They did performances in school auditoriums around Maryland. That was a very important part of life for him as a child.

AV: After his studies, he became an artistic director at the WPA Theater in New York. How did that come about?

SG: He wrote the lyrics for a show the previous producers of the WPA were doing, and as they retired, they basically gave Howard and two other people the rights to use the WPA. It was a way for Howard really to do his art and do his work in a very safe and creatively open environment. His boyfriend at the time was also a director. They did amazing, beautiful work in a very small space.

AV: Was that when you met him, Mr. Lauch?

WL: We both lived at Greenwich Village in New York at that time. Little Shop had just opened and, one Saturday evening, we met in a bar, nearby the Orpheum Theater where his show was played, just after a performance. That was a very active period for him since, between 1984 and 1988, many theater companies were playing his play. There was even a national tour. Howard was very much involved in all that, including in the writing of the movie, in 1986. It was the beginning of his success, just before Disney, and it was very exciting to meet him during that period and share all these experiences with him.

AV: How was it watching him join the world of animation, which is very different from the theater world?

AV: How was it watching him join the world of animation, which is very different from the theater world?

WL: It was a nice change since he was looking for new ways of using his experience in matters of musical theater. And at the same time, he was trying to touch a wider audience. He was very excited about the idea of working in the field of animation. He had already been approached by filmmakers before, but when Jeffrey Katzenberg asked him to work for Walt Disney Feature Animation, it really echoed in him. It was a medium he thought he really could bring something new.

SG: Animation is very different from the theater world but, I think, he always thought visually. So, in that way, it worked, it was fine. What was hard was: Howard truly had to have his finger in every pie, he had to be a part of everything. When he felt strongly about something, he did not sit by quietly. He made sure you knew. He didn’t care if you were Jeffrey Katzenberg or Michael Eisner or anybody else. He would make his thoughts very clear. He was not afraid of people. But he loved comics and animation. He was so interested in that and he was very charmed by the little doodles and the little drawings that they did. Howard always drew, always doodled. All of his notebooks were full of pictures. Here were people who were doing this for a living and I think he was very interested in what they did.

So, there was a real respect for the animators’ art from the very beginning, and obviously, that helped. He wanted to learn. He was a learner. A new skill was interesting to him. So, I think he was able to integrate very well, very easily into animation. The big difference is that, in theater, the director rules. There’s one vision in theater. In film, it’s not always that way. And that, I think, was difficult. If he had lived, frankly, I believe he would have continued to write and gone into directing as well.

AV: Because of his talent and versatility, some compared him even to Walt Disney.

SG: I wouldn’t do that. The only comparison I would make is that they were both absolutely unique in their talents and in their skills. Actually, not even that, they were uniquely visionary. In that way, yes, there is a comparison. I think Howard probably would be very embarrassed to be compared to him. Howard certainly was aware of his talents as all artists are. On one hand, he knew when he was right and was very proud of it when he was right, and on the other hand, he had a lot of concerns about his talents. In that, I think any person who has a lot of talents is that way.

AV: How did you feel about that new departure, from New York theater to Californian film industry?

SG: The most personal of it was that he didn’t move away. He never truly moved to California. He would go out there and then come back. It was very hard to have him move away. The other side of it is that, as he was working on Little Mermaid, early on, it was also when he found out that he was HIV positive. So, it was very hard on a personal level. So, as he was doing this, there was also this great fear for his health and having him far away added to the difficulty.

AV: Among all the subjects that were proposed to him by Disney, he chose a fairytale, which seems kind of unexpected considering what he had worked on previously.

WL: It is true that, at first sight, these worlds seems very different. Little Shop of Horrors seems more of an adult subject. But there is kind of a funny and playful aspect in this piece, and a magical dimension when you think that this plant becomes human in a way and starts to move and sing. Personally, I feel a connection between Howard’s talent to create over the top situations with puppets and his interest in fairytales. Besides, it wasn’t the first time he directed a fairy tale. He had already done The Snow Queen back at the University. And that goes back up to his childhood. It has always been there.

AV: In Little Mermaid he introduced musical styles that were unheard-of in animation, like Calypso. Can you tell me about his musical tastes?

SG: He truly went across the board. He was in to Bruce Springsteen and Emmylou Harris and country music. We both truly adored Nashville by Robert Altman. Everything from there to Wagner, to opera. I don’t actually remember reggae specifically but I do have a notebook of his, a note to himself saying he would love to do a Calypso with the crab! What happened with Sebastian was not so much that Howard wanted to do something Calypso in there because I liked that sound as much as he thought that it would work for that character and would work in the overall pastiche of that film. It was the same with Little Shop. Because it’s set in the time period that it was set in, it was quite obvious that it had to be a 50s, rock ‘n’ roll musical. That was the way to do it. His musical decisions came out of characters although he certainly had love for a lot of different styles.

WL: This diversity of styles in Little Mermaid seems for me to belong rather to musical theater than to pop music because that kind of play on style is somehow natural in musicals. Howard and Alan knew perfectly how to play on that. That’s how they came to that unexpected association between Sebastian and Calypso that makes all the charm of that character and makes him unforgettable!

AV: Did you see him working with the artists?

SG: More in the theater world. But we were invited to a few recording sessions in his film work, like for Little Mermaid. When I think about that, I get tears in my eyes because these moments were absolutely my brother. That’s just what I remember and what I miss most about him because what he was doing in that moment with Jodi (Benson) was him. He was connecting with her and giving to her, in a very personal way. He was a very personal director. That was very much the essence of Howard. He directed a little bit when I was younger and that was absolutely what he gave to people. And it did it in his life as well.

When I said at the beginning of our conversation that he was a director in everything, he truly wanted to get the best part of people. If I was going in the wrong direction with whatever I was doing, he intervened as he did with Jodi! It was also a very paternal way of working with people. Especially to the actresses he worked with. You felt that very real emotion. He was a person who cared for them more than on simply a moment-to-moment director basis. He was very warm, very personal and very direct when he worked with people, and especially when he worked with actresses. I think he had a special connection to Jodi as well.

WL: It was so interesting to be beside him when he was working with artists, and especially for Disney films. Instead of staying sitting, in the distance, watching the artists rehearsing, as you can see directors doing it in the DVD bonus features of some movies, he was standing up beside the sings talking to them in a very intimate way. He even played the scene with them. He had a very clear vision of the emotions behinds words and he wanted to share that with the artists. I remember Angela Lansbury didn’t feel very comfortable with the interpretation of the Beauty and the Beast title song. But everything changed when Howard sat at the piano and sang Beauty and the Beast as if he were Mrs. Potts. It literally transformed Angela Lansbury’s vision and led her to the beautiful performance that you know.

SG: One of the things he was very good at – why he was such a good director and such a creative person – as all good actors do, was losing himself in the character. He did it not so much as an actor but as a writer and as a director. And in that moment that he was directing Jodi, he was acting Ariel. If you listened to the tapes of him working, it was so clear that he truly himself in the character, in the moment. When he was doing Ursula, he was Ursula as well. He was an incredible mimic. He was not the world’s best actor or the world’s best singer, these weren’t his true talents, but he was a wonderful mimic and he could get very personal to his characters.

AV: Ariel wanted to be part of a world above, Belle wanted to live much more than a provincial life. Were they Howard’s desires, too?

SG: We all want that, but Howard knew how to take any human experience. I don’t think anyone is satisfied with what they have and I don’t he was either. In that way, I think he was speaking for himself. He was an artist, and as an artist, even in his most extreme characters, he put himself in them.

WL: Ariel is certainly the archetype of the character who wants something else, something more. I think that was truly part of Howard, part of his love for life and the fact that he was always looking for new challenges. But you can find a similar connection with Audrey, the female character in Little Shop of Horrors, Ariel and Belle. They all dream of a better place and a better life.

AV: The deleted song Proud of Your Boy, from Aladdin, was often thought as being very personal, too.

WL: Probably, there is a connection. In a way, Howard was a child prodigy. He showed dispositions for theater at a very young age and, knowing that his mother was a singer, he always looked for her approbation in that matter. That’s why I think that there might be something deeper in that particular song…

SG: And our mother certainly was proud of her boy!

AV: Where you present during these unique moments when Howard and his musical composer partner Alan Menken were creating their songs?

WL: Most of the time, they liked to work alone, without anyone around. But at the end of the day, I often had the privilege to be able to listen one of their working tapes or even to see them complete a session at the piano. That process was kind of secret, so I feel really fortunate to have been their first audience!

AV: Howard and Alan formed a kind of a magic team. Can you tell me about how they complemented each other?

WL: Indeed, each one of them had a talent that was the complement of the other. And together, they could do thing even more wonderful than what they could do separately. Their songs were totally character-oriented and it was very important for them that the music and the lyric give, each one its own way, information about the character that was singing. That way, music and lyrics could tell different things, but at the same time sound just like one voice. One could enhance the other or soften the other. Howard could be more cynical in his lyrics that Alan in his music, which made Howard’s lyrics more “acceptable” and gave an interesting twist to Alan’s music. It was a wonderful exchange. Take for instance Poor Unfortunate Souls. That heavy musical style was deliberately chose to tell dark things about Ursula, but at the same time, the lyrics, and all the tiniest details of the interpretation, on which Howard and Pat Caroll worked very precisely, offer an interesting counterpoint to the music, for a song both funny and scary. And all that together really was Ursula.

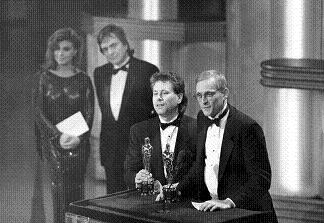

AV: As early as this first collaboration with Disney, The Little Mermaid won two Oscars. How did Howard take to receiving these awards?

SG: He was very modest about it. Also, it was right before he told Alan that he was ill, which was an important moment. It was a difficult time for him. Howard didn’t feel confident anybody would want to work with him, but Alan was wonderful. So, there was a bitter-sweet feeling to him. He was proud, he was happy, his acknowledgment was wonderful but it really wasn’t why he did what he did. It was a wonderful thing for him but he had so many other things at that moment happening in his life that I think he unfortunately really wasn’t able to truly enjoy it as much as he should have.

Through most of the Disney years, he was ill, but he worked till the very end. There was always this undercurrent of fear and “I’ve got to get this done!” When he was working on Beauty and the Beast, the Disney artists would come to him because he couldn’t travel to California. He was at home at one point and I was visiting him. He was all right but he was not feeling well. He showed me some of the roughs from the film. As we were watching the film, he turned to me and said: “It’s going to be good!” He knew Beauty and the Beast was going to work.

WL: Nobody could tell in advance that Little Mermaid would be a success, and when the film proved to be a success, Howard was really pleased. Winning Oscars and Golden Globes was wonderful to him, but the most important things was that the public liked his film. It is all the sadder that he didn’t see the success of Beauty and the Beast and its nomination as best movie for the Academy Awards two years later.

AV: What do you think his motivation was?

SG: Howard did what he did because he had no choice. He was an artist and he had to do that work. If Disney had never come around, I don’t think he would have gone looking for a way to work his way into that world. I think he would have just looked for the next new project, the next way to engage his mind and his creativity, and to express himself.

AV: Production numbers are a big part of musicals, and are part of the Disney films he did. How did he feel about dance?

SG: He was a terrible dancer! I remember watching him when he was in graduate school, he was in a professional acting company, and he did Tames At Sea. He was absolutely charming on stage as the lead, but couldn’t dance. He couldn’t move. He was musical, he had an incredible hear, but he didn’t like to dance, it was not his forte. I think the production numbers were based on his love for musical theater. We went to local musicals and touring musicals growing up and he was just absolutely enamored of the bigness and the silliness and the extremity of musical theater. And I think that, when you get into something like Be Our Guest, it’s really about: “Isn’t this silly? How over the top can we get here?” Howard loved pastiche. So, there is some Busby Berkeley in it. What’s so important is that it worked in the moment of that film. As silly as it, it isn’t a production number slapped in there. It’s the right moment to really see what’s going on in this magic castle. That’s really the reason that that exists. It’s because it was the right moment for it in the film. The same in the Gaston song, or in The Little Mermaid with Under the Sea. He wasn’t a slapstick person but he loved the funniness, the silliness, the language, the word play, and that was everywhere in what he did. When Howard laughed, it was just wonderful!

WL: Sarah’s examples are perfect since they are the highlights of each of those films. They are exuberant, terribly funny, unforgettable, and everybody loves them. As for myself, I would add Poor Unfortunate Souls. To me, that number that takes place within a sequence between Ariel and Ursula is so good in that it manages to express all the most essential aspects of the story just in one song: Ariel’s giving away her voice to be able to get legs, her leaving her family and all the risks she undertaken to make her dream come true. It was a true challenge to create such a rich song, and Howard and Alan really made it a success.

AV: Speaking of language, there are a lot of French words in Howard’s lyrics, from Les Poissons to Aladdin’s “nom de plume”. What’s the reason for those?

SG: Howard studied French in high school. That was the language he studied. He became close friends with his high school French teacher. Bill went to Paris with them. Howard was very enamored of France and of the language, I think because it’s romantic language. I don’t know quite what else was there but I remember him being absolutely charmed when he came back from having been there and talking about the taxi drivers allowing him to attempt his French! Because he was a good mimic and because he wasn’t afraid of sounding silly, he would attempt to speak the language that was a pleasure for him!

WL: That was a wonderful trip. We went to Paris to meet the director of the French version of Little Shop of Horrors. Howard was very involved in the French translation of his musical. The wordplays are very important and the choice of the right words was crucial to express all the nuances. That was a memorable trip for both of us and we really enjoyed all the wonders of Paris!

AV: What connection did he have with his public?

SG: He was not a painter. He was truly an entertainer. He liked to amuse and entertain, even on a very personal level, when getting together with his family or his friends. He could tell stories or tell about the latest musical he saw. He loved an audience. Also, something very important, he respected an audience. He never spoke down to an audience, including an audience of children. He actually wrote about this in his introduction to Little Shop. He wanted to bring the audience to his level. When you think about it, what he offered, one of the things he brought to Disney was that respect for the audience. Katzenberg talked about it when they talked about the adults coming in to Little Mermaid and having a good time. He wrote using his own voice, and his own voice was a smart voice! Howard was a communicator and it was important to him to communicate with people.

AV: Thank you so much for sharing these memories with us!

AV: Thank you so much for sharing these memories with us!

SG: Thank you for your interest. If you look at his work and listen to his music and lyrics, and you listen to what he wrote and you see what he directed, he does exist there. That is what gives me the greatest pleasure.

WL: Thank you. In addition to everything we said, I think the best way to know Howard would have been to let him cook you a dinner, which he did a lot when he had time. He was very generous, and you felt that in that kind of moments.

AV: What would he have prepared?

WL: He was from Baltimore, which is well-known for its seafood. So, sorry for Sebastian, but I guess he would have made a crab cake!

With all our sincerest gratitude to Sarah Gillespie, William Lauch and Rick Kunis.